Consultation-liaison psychiatry is a branch of clinical psychiatry that enables psychiatrists to carry out a series of activities within a general hospital. The number of liaison psychiatry units around the world has increased significantly, and Peru is no exception. However, this development is heterogeneous and unknown, so recent study reports are required to reveal the characteristics and details of the clinical care services provided by these units.

AimTo describe and report the socio-demographic and clinical characteristics of patients evaluated in the Liaison Psychiatry Unit of the Guillermo Almenara Irigoyen National Hospital in Lima, Peru, and to analyse the symptomatic and syndromic nature of the identified conditions.

MethodsCross-sectional descriptive study. Referrals to the Liaison Psychiatry Unit of the Guillermo Almenara Irigoyen National Hospital between May and October 2019 were studied, and a factor analysis of the symptoms was conducted.

ResultsIn a total of 400 referrals evaluated, the average age was 58 ± 17.09 years and 61.5% of the patients were women. The rate of psychiatric consultation was 2.73%. Internal medicine (13.9%) was the service that most frequently requested a psychiatric consultation. The disorder most frequently diagnosed was anxiety (44%), and the symptoms most frequently found were depression (45.3%), insomnia (44.5%), and anxiety (41.3%). The most used treatments were antidepressants (44.3%). The exploratory factor analysis of the symptoms showed three syndromic components: delirium, depression, and anxiety.

ConclusionsThe typical patient of this sample is a woman in her late 50s, suffering from a non-psychiatric medical illness, and with anxiety disorders as the main diagnosis resulting from the psychiatric consultation.

La psiquiatría de interconsulta y enlace es un área de la psiquiatría clínica cuya función es que psiquiatras lleven a cabo una serie de actividades dentro de un hospital general. En el contexto internacional, el número de unidades de psiquiatría de enlace se ha incrementado significativamente, situación que está repercutiendo en Perú. Sin embargo, este desarrollo es heterogéneo y desconocido, por lo que se requieren reportes de estudios recientes que revelen las características y los detalles de los servicios de atención clínica de estas unidades.

ObjetivoExaminar y reportar las características sociodemográficas y clínicas de los pacientes evaluados en la Unidad de Psiquiatría de Enlace del Hospital Nacional Guillermo Almenara Irigoyen (HNGAI) de Lima, Perú, y analizar la naturaleza de los cuadros sintomáticos y sindrómicos presentes.

MétodosEstudio descriptivo y transversal de las interconsultas recibidas por la Unidad de Psiquiatría de Enlace del HNGAI entre mayo y octubre de 2019; se aplicó un análisis factorial de los síntomas.

ResultadosEn el total de 400 pacientes vistos en interconsulta, la media de edad fue 58 ± 17,09 años. El 61,5% eran mujeres. La tasa de derivación fue del 2,73%. El servicio con el mayor número de referencias fue Medicina Interna (13,9%). Los trastornos más frecuentes fueron de naturaleza ansiosa (44%); los síntomas más frecuentes fueron ánimo depresivo (45,3%), insomnio (44,5%) y afecto ansioso (41,3%). Con respecto al tratamiento, el más prescrito fue con antidepresivos (44,3%). El análisis factorial exploratorio de los síntomas mostró 3 factores o componentes sindrómicos importantes: delirio, depresión y ansiedad.

ConclusionesEl paciente típico de esta muestra es una mujer al final de su quinta década de vida, con enfermedad médica no psiquiátrica y con evidencia de trastornos ansiosos como diagnóstico principal resultante de la interconsulta psiquiátrica.

Consultation-liaison psychiatry, also known as psychosomatic medicine in some countries, is defined as an area of clinical psychiatry which includes diagnostic, therapeutic, teaching and research activities carried out by psychiatrists (with the support of nursing, psychology and social care staff) in units, services or departments of a general hospital.1 Since the first articles by Lipowski,1–3 the objectives, organisation and functions of consultation-liaison psychiatry have developed considerably. In its beginnings, clinical activity (diagnostic and therapeutic) began with responses to consultations requested by non-psychiatric medical staff, which, directly or indirectly promoted the biopsychosocial approach to patient care. The teaching activity focuses on training medical students, medical residents and assistants, as well as non-medical staff, in the basic concepts of the biopsychosocial perspective. Lastly, the research activity ranges from the epistemological aspects of the mind-body relationship to the clinical and practical aspects.4 As Alarcón and Matos5 rightly point out, “general hospital psychiatry thus becomes the foundation for those of us who believe in the medical essence of our discipline”.

Historically, the development of consultation-liaison psychiatry took place in the United States in the 1920s and 1930s, under the influence of the psychoanalytically orientated psychosomatic movement, which later spread to different countries around the world.6 In Peru, this movement was introduced by Carlos Alberto Seguin, who worked from 1942 to 1945 with Flanders Dunbar, a figure internationally recognised for his work in psychosomatic medicine.7 The Psychiatry Department that Seguin founded in 1945 at Hospital Obrero de Lima —today Hospital Nacional Guillermo Almenara Irigoyen (HNGAI)— was the first of its kind in Latin America. It would become a study and research centre producing an increasing number of national and international publications, which brought a significant level of prestige to the “Peruvian psychosomatic school”.8 One of these pioneering research studies was carried out in 1972 by José Alva, who examined 863 referrals to the HNGAI General Psychiatric Department. In his study, 68.49% of the patients were male, with a referral rate of 4.15%. The departments that made the most referrals were Endocrinology, General Medicine, General Surgery and Gastroenterology. In concluding, he pointed out, “It is surprising that, going by the frequency rates, many departments do not use the resource of consultations. Perhaps these departments do not give the due importance to the psychological and psychopathological aspects of medical care provision”.9

This situation appears to have persisted to the present day. A study by the European Consultation-Liaison Workgroup for General Hospital Psychiatric and Psychosomatics documented that only 1.4% of patients admitted to a general hospital had been referred to liaison psychiatric services, despite an estimated 10% of hospitalised patients requiring some form of psychiatric care.10 It is therefore essential to gradually optimise the possibilities available for patients from the psychiatric department. It has been shown that a systemic approach, which includes the participation of staff from consultation-liaison psychiatry units, among other benefits, could improve the quality of life of patients, reduce the length of hospital stay, reduce costs and humanise medical care.11 Although there has been an increase in consultation-liaison psychiatric units and services in general hospitals around the world, as in Peru, it is evident that implementation has not been uniform in this country, adding to which is the lack of recent national research data on the characteristics of the consultation-liaison psychiatric care.5,9,12 In this context, the aim of this study was to examine and report on the demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients treated at the HNGAI Liaison Psychiatric Unit from May to October 2019. As a secondary objective, we analysed the different groupings of symptoms and syndromes of the clinical manifestations reported by patients.

Materials and methodsStudy designThis was an observational, descriptive, cross-sectional study, which analysed the referrals received in the General Psychiatry Department’s Liaison Psychiatric Unit at the HNGAI in Lima, Peru, from May to October 2019. The results are presented in accordance with the guidelines of the STROBE initiative.13

Clinical contextBy number of beds, the HNGAI is the second largest public hospital in Peru (it has a total of 815 hospital beds), in addition to being a tertiary centre of reference for all medical specialities, including psychiatry. It attends to the health needs of 1,547,840 registered people. Because it treats practically all diseases, from the simplest to the most complex, it was classified in 2015 as a Specialised Health Institute III-2, the highest level granted by the Peruvian Ministry of Health to hospital establishments.

The HNGAI Psychiatric Department has four services. The Psychiatric Liaison Unit is part of the Adult Psychiatric Service and was inaugurated in 2010. There are currently three part-time psychiatrists working there, plus support from third-year Psychiatry resident doctors, who do academic and care rotations. Three types of activities are carried out in this unit: (a) clinical practice, through which requests for consultations from other services are responded to, and psychosocial follow-up and support is carried out in certain cases; (b) academic, clinical training for medical residents, clinical discussions and contacts with other medical specialities through courses and conferences; and (c) research, in which databases are generated and lines of research developed, leading to publication of scientific articles.14–17 At the same time, the Addictive Behaviours and Child and Adolescent Psychiatric services have psychiatrists who respond to referrals to these services.

ParticipantsIn this study, in order to adapt to the objectives, we used a non-probabilistic sampling method. The sample consists of all patients over 18 years of age hospitalised in non-psychiatric departments of the HNGAI, for whom a consultation was requested from the Adult Psychiatric Service’s Liaison Psychiatric Unit from May to October 2019.

Variables and data sourcesSince April 2019, the HNGAI has had an electronic medical record system, which facilitated data collection. The Liaison Psychiatric Unit referrals requests virtually. The patients were prospectively assessed from May 2019 using a computerised clinical database, created with Microsoft Excel and supported by the guidelines set out by the European Consultation/Liaison Workgroup (ECLW) for data collection.18 The following variables were collected in the database for this study:

- •

Sociodemographic variables: age, gender and personal psychiatric history.

- •

Characteristics of the consultation: date, referring department.

- •

Clinical variables: presence of the following symptoms as reported in the medical history: depressed mood, manic mood, anxious affect, irritability, catatonia, hallucinations, delirium, extravagant behaviour, formal thought disorder, inappropriate affect, anhedonia, poverty of speech, abulia/apathy, emotional blunting, obsessions, compulsions, suicidal ideation, suicidal acts, insomnia, altered consciousness, impaired attention and cognitive impairment.

- •

Interventions and outcome:

- –

Follow-up (number of interventions in one patient, requested by the psychiatrist in complex cases that require further assessment for adjustment of psychopharmacological treatment or psychotherapeutic support).

- –

Diagnosis according to ICD-10 categories.

- –

Treatment: psychotherapy and psychosocial support, antipsychotics, antidepressants, mood stabilisers, anxiolytics (benzodiazepines and non-benzodiazepines such as Zolpidem; antipsychotics, antidepressants, or mood stabilisers were not included).

- –

Outcome (discharge, follow-up or transfer to psychiatric hospital).

- –

Descriptive statistics techniques were used, and summary and standard deviation measures were calculated for quantitative variables, and proportions for qualitative variables.

An exploratory factor analysis was carried out with symptoms as variables, using the principal component analysis method, and then adjusted by Varimax rotation with Kaiser normalisation. The feasibility of a factor analysis of symptoms was evaluated using the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy and Bartlett’s test of sphericity. The number of factors was determined using the criterion of an eigenvalue >1. The significance level for this study was p < 0.05. The data were analysed with the IBM SPSS version 23 statistics program.

Ethical considerationsThis study followed the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The approval of the Head of the HNGAI Psychiatric Department was obtained for the data collection.

ResultsSociodemographic characteristicsWe analysed a total of 532 patients examined during the study period. According to the selection criteria, 132 assessments were excluded because they were not carried out by the Adult Psychiatric Service’s Liaison Psychiatric Unit (63 were by the Child-Adolescent Psychiatric Department and 69 by the Addictive Behaviour Service). That left us with a total of 400 assessments. The average age was 58 ± 17.09 years (range 21–92). A total of 144 patients (36%) were over 65. Other relevant sociodemographic characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of 400 patients assessed by the Adult Psychiatric Service’s Consultation-Liaison Psychiatric Unit.

| Variable | |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 58 ± 17.09 (21–92) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 154 (38.5) |

| Female | 246 (61.5) |

| Month | |

| May | 68 (17) |

| June | 54 (13.5) |

| July | 60 (15) |

| August | 63 (15.8) |

| September | 74 (18.5) |

| October | 81 (20.3) |

| Underlying disease | |

| Psychiatric | 102 (25.5) |

| Non-psychiatric medical | 298 (74.5) |

The values express mean ± standard deviation (range) or n (%).

During the study period, 14,620 patients were discharged from the HNGAI. The rate of referral to the Adult Psychiatric Department’s Liaison Psychiatric Unit was 2.73%. The departments that most requested psychiatric assessment were Internal Medicine (13.9%), Respiratory Medicine (7.5%), Gynaecology (7%), Neurology (7%) and General Surgery (7%). The other referring departments are shown in Table 2. Table 3 shows the reasons for the referral.

Department of origin of the requests for assessment of 400 patients by the Adult Psychiatric Service’s Consultation-Liaison Psychiatric Unit.

| Department | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Internal medicine | 55 | 13.9 |

| Respiratory medicine | 30 | 7.5 |

| Gynaecology | 28 | 7.0 |

| Neurology | 28 | 7.0 |

| General surgery | 28 | 7.0 |

| ICU | 22 | 5.5 |

| Geriatrics | 21 | 5.3 |

| Dermatology | 19 | 4.8 |

| Endocrinology | 19 | 4.8 |

| Gastroenterology | 18 | 4.5 |

| Thoracic surgery | 17 | 4.3 |

| Orthopaedic Surgery | 16 | 4.0 |

| Obstetrics | 13 | 3.3 |

| Rheumatology | 11 | 2.8 |

| Nephrology | 10 | 2.5 |

| Kidney transplant | 10 | 2.5 |

| Liver transplant | 9 | 2.3 |

| Urology | 9 | 2.3 |

| Cardiology | 7 | 1.8 |

| Oncology | 6 | 1.5 |

| Neurosurgery | 5 | 1.3 |

| Plastic surgery | 5 | 1.3 |

| Immunology | 3 | 0.8 |

| Haematology | 3 | 0.8 |

| Otorhinolaryngology | 3 | 0.8 |

| Head and neck surgery | 2 | 0.5 |

| Infectious diseases | 1 | 0.3 |

| Hand surgery | 1 | 0.3 |

| Breast disease | 1 | 0.3 |

Reasons for assessment of 400 patients by the Adult Psychiatric Service’s Consultation-Liaison Psychiatric Unit.

| Reason | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Assessment of a patient with psychiatric illness | 70 | 17.5 |

| Mental disorders related to somatic disorders | 178 | 44.5 |

| Mental disorders not related to somatic disorders | 149 | 37.3 |

| Medical-surgical problems deriving from mental disorders (e.g. medical complications of addictions, suicidal behaviour, anorexia, etc.) | 3 | 0.8 |

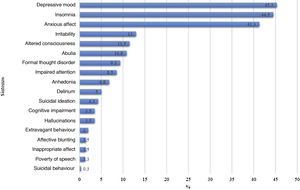

The most common mental symptoms were depressed mood (45.3%), insomnia (44.5%) and anxious affect (41.3%). Other mental symptoms are shown in Fig. 1. In this sample, the most common diagnosis was anxiety disorder (44%), followed by mood disorder (20.8%). More diagnoses are shown in Table 4.

Clinical characteristics of 400 patients of the Adult Psychiatric Service’s Consultation-Liaison Psychiatric Unit.

| Variable | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Main diagnosis | ||

| Schizophrenia spectrum disorders (F2X) | 12 | 3 |

| Mood disorders (F3X) | 83 | 20.8 |

| Anxiety disorders (F4X) | 176 | 44 |

| Personality disorders (F6X) | 5 | 1.3 |

| Organic mental disorders and dementias (F0X) | 67 | 16.8 |

| Substance use disorders (F1X) | 1 | 0.3 |

| Intellectual disability and autism (F7X-F8X) | 1 | 0.3 |

| Instinct disorders (F5X) | 4 | 1 |

| Mentally healthy | 39 | 9.8 |

| No diagnosis | 12 | 3 |

| Treatment | ||

| Not indicated | 37 | 9.3 |

| Psychotherapy and psychosocial support | 112 | 28 |

| Antipsychotics | 90 | 22.5 |

| Antidepressants | 177 | 44.3 |

| Mood stabilisers | 30 | 7.5 |

| Anxiolytics | 167 | 41.8 |

| Destination of the patient | ||

| Discharge | 137 | 34.3 |

| Requires follow-up | 244 | 61 |

| Transfer to psychiatry | 1 | 0.3 |

The feasibility tests for the factor analysis were satisfactory (Bartlett’s sphericity test: χ2 = 782.799; p < 0.001; KMO value = 0.700). To form comprehensive grouping, the symptoms were reduced to three syndrome factors: 1 = delirium (eigenvalue, 2.542 with a variance of 19.54%), 2 = depressive syndrome (eigenvalue, 2.141 with a variance of 16.46%), and 3 = anxiety syndrome (eigenvalue, 1.359 with a variance of 10.45%). Table 5 shows the grouping of symptoms in the three factors.

Exploratory factor analysis of the symptoms of 400 patients of the Adult Psychiatric Service’s Consultation-Liaison Psychiatric Unit Extraction method: principal component analysis. Varimax rotated solution with Kaiser normalisation.

| Factors | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| Formal thought disorder | 0.744 | ||

| Extravagant behaviour | 0.637 | ||

| Hallucinations | 0.628 | ||

| Impaired attention | 0.575 | ||

| Altered consciousness | 0.572 | ||

| Delirium | 0.569 | ||

| Anhedonia | 0.792 | ||

| Abulia | 0.711 | ||

| Suicidal ideation | 0.642 | ||

| Depressive mood | 0.579 | ||

| Anxious affect | 0.659 | ||

| Insomnia | 0.621 | ||

| Irritability | 0.493 | ||

Factor 1: delirium. Factor 2: depressive syndrome. Factor 3: anxiety syndrome.

The main treatment recommendation was the use of antidepressants (44.3%), followed by anxiolytics (41.8%). Follow-up was indicated for a total of 244 patients (61%), of whom 85 (21.25%) had two assessments and 27 (6.75%) required three or more. Other clinical characteristics are shown in Table 4.

DiscussionThe results show a higher rate of referrals for females, a finding similar to that observed in other psychiatric consultation-liaison units.12,19–22 However, in a previous study carried out at our hospital in 1972, the referral rate was higher for males (68.49%). This difference could be due to the changes in the policies on Social Security coverage in Peru: in the past, the HNGAI mainly served the working population, made up mostly of men. In terms of age, 36% of the sample was made up of patients over the age of 65. According to the literature, around 30% of psychiatric consultations are requested for people over 65.23 However, this differs from the pioneering study carried out in the HNGAI in 1972, where only 6.37% of the referrals to psychiatry were for patients over 60.9 Today the geriatric population is constantly increasing, which means a greater number of psychiatric assessments in this population.24–26 In the future, psychiatric consultation-liaison units will need healthcare professionals trained in psychogeriatrics to appropriately address the specific needs of this sector of the population.26 An example of this is the Liaison Psychiatric for Older Adults Service at King’s College Hospital, which plays an important role in mental healthcare for the over-65s admitted there.27 We should point out that our results showed more consultations with the Adult Psychiatric Department, probably because there are no specific liaison programmes in the other services. Hence the importance of consultation-liaison Psychiatric units also having child and adolescent psychiatrists and psychiatrists specialising in addictive behaviours.

The rate of referral to the Liaison Psychiatric Unit in the period studied was 2.73%. This figure is similar to that reported in other studies around the world. The referral rate ranges from figures as low as 0.006% up to 5.8%.25,28–32 Previous studies have documented a prevalence of mental disorders in hospitalised patients of 11.8% to 38.7%.33,34 A recent meta-analysis concluded that psychiatric comorbidity is related to increased length of stay in hospital (4.38 days, compared to patients without psychiatric comorbidity), higher medical costs and more readmissions.35 Adequate intervention in these patients is therefore very important, despite the very low referral figures. The lack of referral may be due to a number of factors, including poor communication between the consultation-liaison psychiatrists, the belief that any medical professional can treat mental symptoms, insufficient recognition of mental symptoms and stigma.36,37 Referrals may also be limited by the administrative requirements of the hospital or insurance coverage, which is a recurring problem, particularly in general hospitals, with the exception of the HNGAI, as the Peruvian Social Security system fully covers psychiatric care.

According to other studies, most referrals come from internal medicine departments.5,9,22,25,28–30,38 According to one meta-analysis,36 this is probably because internal medicine specialists have greater sensitivity for recognising psychiatric problems.38 Most of the studies reviewed maintain that the second largest number of referrals to psychiatry comes from general surgery.5,9,21,22,38 However, that was not the case in our sample, where requests from Respiratory Medicine (7.5%), Gynaecology (7%) and Neurology (7%) all had similar rates to General Surgery (7%). This may be due to the fact that these departments have clinical protocols, which specifically include psychiatric assessment for patients diagnosed with tuberculosis, gynaecological cancers and Parkinson’s disease respectively. Another possible explanation could be the type of condition prevalent in a developing country like Peru, where infectious lung disorders are common. This pattern may particularly characterise the HNGAI compared to other hospitals run by the Ministry of Health and the Armed Forces in Peru. The lack of recent publications on the characteristics of care in other psychiatric consultation-liaison units in the country makes it difficult to compare the results.

The most common mental symptoms identified in the patient sample were depressed mood, anxious affect and insomnia. Subjecting the symptoms to factor analysis, we found they could be reduced to three syndrome factors: delirium (formal thought disorder, bizarre behaviour, hallucinations, delusions, altered consciousness and impaired attention); depression (anhedonia, abulia, suicidal ideation, depressed mood); and anxiety (anxious affect, insomnia, irritability). Although there are no previous studies with which to compare these results, the grouping of symptoms was related to the diagnostic findings. Consultation-liaison psychiatrists are tasked with assessing and treating these groups of symptoms. Sánchez-González et al.25 maintain that the main focus of the intervention of such psychiatrists, regardless of diagnosis, continues to be treating the clinical manifestations of delirium and adjustment and mood disorders. Consequently, consultation-liaison psychiatrists need to collaborate closely with other doctors and provide them with the clinical skills necessary to adequately identify these syndromes.39

As regards the diagnoses, a higher prevalence of anxiety disorders was found, followed by mood disorders and organic mental disorders. This is in line with other studies, albeit with slight variations. In some, the main diagnoses are anxiety disorders40; in others, mood disorders, specifically depression,19,38,41,42 cognitive disorders (delirium, dementia)43 or those related to substance use.25 In our sample, the main diagnosis was anxiety disorders, coinciding with the previous study from 1972. This suggests that, despite the sociodemographic changes already described, the anxiety disorder diagnosis continues to be the most common. We should also point out that, in our sample, the percentage of patients diagnosed with substance use disorders was minimal, as the hospital has the Addictive Behaviour Service mentioned earlier and their psychiatrists respond to referrals of that type.

In line with the findings of Lücke et al.,42 the most common psychopharmacological treatments in our study were antidepressants and anxiolytics. Greater prescribing of antidepressants would suggest that assessments based on a consultation-liaison model of psychiatry focus on long-term treatment and outcomes, which differs from prescribing patterns in psychiatric emergency departments, where the use of antipsychotics and anxiolytics predominates.42,44 The indication for psychotherapy treatment and psychosocial support was second in frequency to the use of antidepressants and anxiolytics. Since its inception, the psychiatrists at the HNGAI have proposed that “minor” psychotherapy, in particular advice, catharsis, emotional support and intervention with the family, should be the responsibility of the non-psychiatrist doctor in charge of the patient, leaving major psychotherapy in the hands of the specialist.45

Regarding the scope of this study, we must mention the limitations in the methodology. The results we present here cannot be generalised, as they are limited to a single hospital. Although the situation of the HNGAI may be similar to that of other public hospitals in Peru, the particular characteristics of care in other consultation-liaison psychiatry units in other hospitals run by the Ministry of Health and the Armed Forces need to be studied. For future studies, we therefore recommend analysing variables such as the length of hospital stay of referred patients versus hospital stay of non-referred patients, and by department, so that the differences can be identified. We considered the presence (or absence) of mental symptoms as stated in the medical records. However, future research should use standardised tools for quantitative collection of mental symptoms to produce statistical analyses.

To conclude, the typical patient in the sample assessed by the HNGAI Liaison Psychiatry Unit is a woman, in her late forties, who has a non-psychiatric medical illness and suffers from anxiety as the most prevalent emotional symptom. This study, directed by the Liaison Psychiatric Unit of a pioneering Psychiatric Department, which has been a vigorous advocate of psychosomatic medicine in Peru for 77 years,45 may help standardise clinical procedures used in similar services and circumstances in Peru.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

The authors wish to express their sincere thanks to Dr Renato D. Alarcón for reviewing this article and for his suggestions.

Please cite this article as: Huarcaya-Victoria J, Segura V, Cárdenas D, Sardón K, Caqui M, Podestà Á. Caracterización de las atenciones de la unidad de psiquiatría de enlace durante seis meses en un hospital general de Lima, Perú. Rev Colomb Psiquiat. 2022;51:105–112.