In order to try and reduce the rapid spreading of the coronavirus disease (COVID-19), all of the countries affected have imposed total or partial bans on travel and implemented a series of practices (e.g. “social distancing”, “isolation”, “physical distancing”, “quarantine”, etc.) to prevent people from meeting in large numbers.1 Although these routines are designed to limit people's exposure to the fatal virus, they can also cause fear and anxiety about infection among those practising these new routines.2 Recent studies on psychological effects during the COVID-19 pandemic indicate rates of anxiety and depression that are higher than usual among the population,3 which increase the risk of more recurrent physical and mental diseases, making it difficult to cope with the pandemic.4,5

Due to the importance of appropriate screening to assess and score the most common symptoms of COVID-19-related anxiety, the Coronavirus Anxiety Scale (CAS) by Lee6 was considered. This is one of the most commonly-used instruments in COVID-19 research7 and it consists of 5 items rated on a 5-point Likert scale. It is designed to efficiently and effectively help healthcare professionals and researchers to identify likely cases of dysfunctional anxiety associated with the COVID-19 pandemic. Each item of the CAS taps a distinct physiologically-based fear or anxiety reaction to coronavirus-related thoughts or information. The CAS has been translated into multiple languages and has led to various investigations as part of The Coronavirus Anxiety Project initiative (https://sites.google.com/cnu.edu/coronavirusanxietyproject/home), through which access was granted to the Spanish version for this study.

This instrument was used on a group of 450 Peruvian adults (57.11% female; mean age 34 years) using Google Forms, with an attached consent form, and assessments took place during July and August.

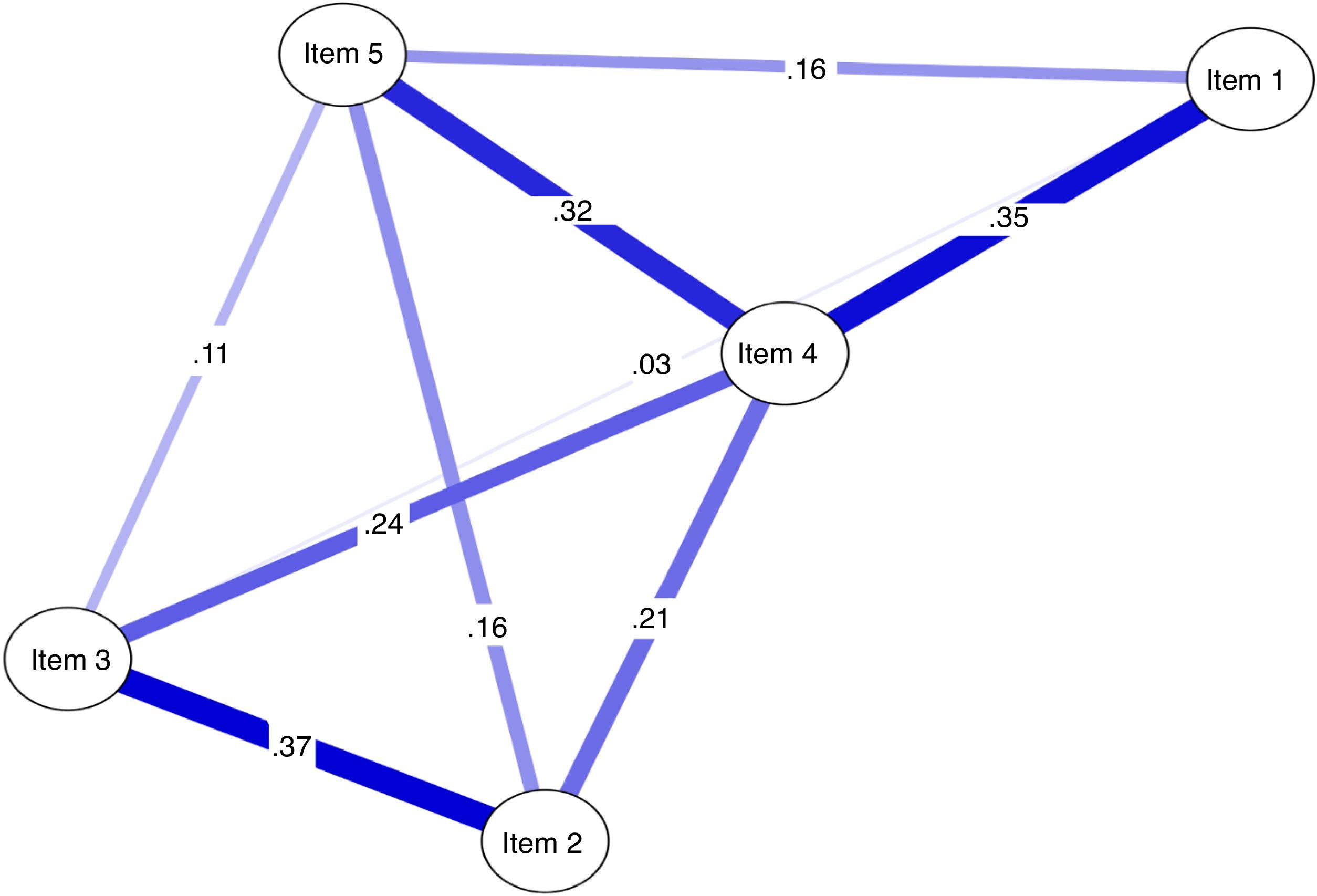

The Gaussian graphical model (network of partial correlation coefficients) was estimated after considering the 5 items of the CAS using the R packages qgraph and graphical LASSO (least absolute shrinkage and selection operator) to regulate the most significant correlations by eliminating spurious correlations.7 This multivariate analysis, known as network analysis, estimates statistical coefficients of effect size (≤0.2, small; >0.2–<0.5, medium; ≥0.5, large)8 and determines the extent of network connections. It also allows us to estimate the degree centrality index that quantifies the importance of the magnitude of the network connections.9 Another technique used was the bootstrapping of 5000 samples to confirm the stability of the network results.

The results show that item 4 (“I lost interest in eating when I thought about or was exposed to information about the coronavirus”) shows a higher strength centrality value (1.61), which means that it is the item, according to the network, that has the greatest influence on connections to other items, with a location that is more central and closer to the other network items. This strengthens the functioning of the symptoms of the CAS, in which all associations are moderate values,9 unlike the rest of the items. Its closer relationship with item 1 (“I felt dizzy, lightheaded or breathless when I read or listened to news about the coronavirus”) can be interpreted as the higher prevalence of loss of appetite being reinforced by the feeling of numbness upon exposure to information about COVID-19. This is the most concurrent interaction promoting the functional activity of the CAS (Fig. 1). Likewise, the association between item 2 (“I had trouble falling or staying asleep because I was thinking about the coronavirus”) and item 3 (“I felt paralysed or frozen when I thought about or was exposed to information about the coronavirus”) suggests a larger extent of the effect (partial r=0.37), greater difficulty sleeping and feelings of chills upon exposure to information about COVID-19, which contribute more to the symptom dynamics of anxiety due to COVID-19 according to the network approach (Table 1).

Coronavirus Anxiety Scale items.

| 1. | I felt dizzy, lightheaded or breathless when I read or listened to news about the coronavirus |

| 2. | I had trouble falling or staying asleep because I was thinking about the coronavirus |

| 3. | I felt paralysed or frozen when I thought about or was exposed to information about the coronavirus |

| 4. | I lost interest in eating when I thought about or was exposed to information about the coronavirus |

| 5. | I felt nauseous or had stomach problems when I thought about or was exposed to information about the coronavirus |

The importance of alternative methods to assess the impact of COVID-19, like network analysis, makes it possible to report specific findings that help the healthcare professionals to more accurately identify the most prevalent items that reinforce the dysfunctional dynamics of anxiety due to COVID-19, as in this study. This specific long-term condition may cause physical and mental functioning to deteriorate and may even lead to a serious clinical disorder as a result of the lack of treatment due to the pandemic.

Therefore, these results make a valuable contribution to the evaluation, through health questionnaires, for use in the detection and treatment of the negative effects of COVID-19, and they are greatly important for research as a contrast model that can be complemented with other methodologies. The fact that the sample is from a single city must be considered a limitation of this study and therefore the possibility of expanding the study to different socio-demographic groups should be considered for future studies.

Above all, this study presents a highly relevant methodology for the COVID-19 pandemic that is applicable in any context and for future research by this journal.