Major depressive disorder (MDD) is a multifactorial disease in which, due to the interaction of several variables, the vulnerability of suffering from it increases. Several models, such as the diathesis–stress model, have explained these interactions. However, experiencing stressful events does not always lead to the development of MDD, and the attribution and appraisal of stressful events contributing to further development of depression symptoms has been considered as a possible explanation.

ObjectiveTo determinate the association and the predictive power of the frequency and appraisal of stressful life events to predict MDD symptomatology.

MethodsCase–control study with 120 psychiatric patients and 120 people from the general population. A structured clinical interview and the life events questionnaire (Sandín and Chorcot) were used to evaluate the sample. The data were analysed with non-parametric tests and binary logistic regression.

ResultsThe psychiatric patients reported significantly higher levels of negative affect, frequency of stressful life events, perceived stress, negative appraisal of the situation and lack of perceived control. The binary logistic regression model indicated that poor perception of control of the stressful event is the most determining factor, followed by negative evaluation of the situation.

ConclusionsThe attributions that are made regarding a stressful event are variables that predict MDD, specifically the assessment of the perceived control over the situation. These results concur with the aetiological models of MDD, such as the cognitive diathesis–stress model.

El Trastorno depresivo mayor (TDM) es una enfermedad multifactorial en la que, por interacción con diversas variables, se incrementa la vulnerabilidad a padecerla. Diversos modelos han explicado las interacciones, como el de diátesis-estrés. Vivir eventos estresantes no siempre lleva a la aparición del TDM, y se ha planteado que la atribución y la valoración de los eventos estresantes podrían ser un mejor predictor de la aparición de los síntomas.

ObjetivoDeterminar la asociación y el poder predictivo de la frecuencia y la valoración de eventos vitales estresantes en la presencia de sintomatología del TDM.

MétodosEstudio de casos y controles con 120 pacientes psiquiátricos y 120 personas de la población general. Se utilizó una entrevista clínica estructurada y el Cuestionario de Sucesos Vitales de Sandín y Chorot. Los datos se analizaron con pruebas no paramétricas y regresión logística binaria.

ResultadosEl grupo de casos obtuvo significativamente más altos en afecto negativo, frecuencia de eventos estresantes, nivel de estrés percibido, valoración negativa de la situación y percepción de no control. El modelo de regresión logística binaria indicó que la baja percepción de control frente al evento estresante es el factor más determinante, seguido por la evaluación negativa del evento.

ConclusionesLas atribuciones realizadas sobre los eventos estresantes son determinantes en la presentación del TDM, en especial la valoración del control percibido frente a los sucesos vitales, en concordancia con los modelos etiológicos del TDM de diátesis cognitiva al estrés.

According to the World Health Organisation (WHO),1 depression is one of the leading causes of disability and one of the most prevalent mental illnesses in the world. An estimated 350 million people are affected by depression. In Colombia, the most recent mental health study carried out by the Ministry of Health2 established that the prevalence of major depressive disorder (MDD) in the adult population is 4.3%, while minor depression occurs in 1% and dysthymia in 0.5%. These figures are important, as they show that there is a higher prevalence of this disorder in the Colombian population compared to other mental disorders.

With the symptoms being so disabling,3 patients have been found to have maladaptive coping strategies, lower academic and occupational achievements, difficulties in interpersonal and work relationships and, in general, negatively affected life cycle goals.4 In addition to the symptoms, MDD has been described as a multifactorial disease involving environmental, contextual, individual, genetic and biological variables which increase susceptibility to development of the disorder.5–7

One of the most common models in the aetiology of depression is the diathesis-stress model, which establishes that the development of MDD is the result of the interaction of genetic and environmental factors.6–10 The literature shows that the degree of heritability of depression ranges from 31% to 42%.5 In multi-generational studies it has even been found to be as high as 67%.11 Although they demonstrate high heritability rates, most studies report that gene expression related to MDD is highly influenced by environmental factors such as exposure to stressful and traumatic events,12,13 which become environmental susceptibilities in the aetiology of the disorder.

However, having experienced adverse or stressful events does not always lead to depression. For this reason, the transactional model of stress14 suggests that stressful situations are the result of interactions between the subject and their environment, where the impact of a certain stressor is mediated by how the person interprets the event and the psychological, social and cultural resources they perceive to cope with the situation.15,16 Dobson and Dozois7 proposed that MDD was the result of exposure to stressful events in response to which people have maladaptive cognitions. This gives rise to the model of cognitive diathesis to stress, which establishes that negative thoughts and the interpretations of these events can be regarded as cognitive causes of the development of depression.17,18

Recently, Beck and Bredemeier19 asserted that negative perceptions and evaluations precipitate negative beliefs that reinforce the establishment of schemes that skew the processing of information. The above, and biological reactions to stress, mediated by genetic variants, predispose the individual to suffer clinical symptoms of depression.

In this order of things, the maladaptive processing of information and the negative appreciations of important events in people's lives are decisive for the development of depression.20,21

Taking the above into account, a stressful event is understood as a sudden and abrupt change in the context to which a person is exposed which causes alterations that require adjustment processes. These changes are called life events, and may include diminished or unstable income, the death of close family or friends, a change of partner, separations, estrangement from loved ones, loss of employment or academic difficulties.22,23 In other words, life events are objective experiences that cause a substantial readjustment or a degree of change that affects physical and psychological well-being and requires the person to carry out actions or changes in their behaviour to restore the lost balance.15

There are also minor stressors, considered to be events with less impact, although they occur with more frequency in everyday life. They are often related to difficulties in fulfilling the different roles a person may have, as an employee, parent, partner or child, for example. Some authors suggest that this type of daily stress is a better predictor of health alterations22,23 and could be a significant component in the development of mental illness. Factors such as the frequency, intensity, appraisal and complexity of the stressful event as it is perceived by an individual can generate an accumulation of apparently threatening negative experiences, affecting the person's physical and mental health.24,25

However, the cognitive component associated with the appraisal of life events as stressors is usually mediated by attribution processes,26–28 “the causes that people adduce to explain the situations they experience”. Abramson et al.26 proposed three attributional dimensions: (a) internality–externality (depending on whether the cause is inside or outside the actual individual); (b) stability–instability (in relation to whether the cause is maintained over time), and (c) generality–specificity (taking into account that the cause affects other areas of the person's life or, conversely, is limited to the specific situation being assessed). These attributional dimensions can be classified as positive (external, unstable and specific) or negative (internal, stable and general) styles, the latter being of interest to this research, as they have been associated with both the development of depressive symptoms and with different indices of poorer physical health.29,30 Thus, the importance of the attribution or appraisal made of a certain life event may be more significant than the actual event, which could demonstrate the relevance of the explanatory styles in the development of MDD.

Taking the foregoing into account, the objective of this study was to establish whether the frequency of stressful life events, the level of stress they generate and the appraisal made of them (positive/negative, controlled/uncontrolled, expected/unexpected) predicts the development of MDD, based on the hypothesis that the appraisal of events will have a greater predictive weight than the frequency with which events are reported. To answer this question, the first objective is to confirm the differences in terms of negative affect and depressive symptoms between a group of patients diagnosed with MDD from two psychiatric clinics in the city of Bogotá and a control group; the second object was to establish whether or not there are significant differences in relation to the frequency of stressful events and the appraisal of these events (understood as the degree of perceived stress, whether the event was expected or unexpected, controllable or uncontrollable and finally negative or positive), and to determine the variance explained by the above variables, the explanatory power and the prediction rate of development of depression.

Material and methodsStudy of groups of cases and controls statistically comparable by gender and age. Sampling was non-probabilistic and sequential.

ParticipantsThe analyses were based on a sub-sample of 120 cases and 120 controls aged over 18 years from the “Perceived stress and genetic and epigenetic markers in major depressive disorder” project, funded by Colciencias (Application procedure 712 Basic Science), divided into two groups:

- •

Group of 120 patients (mean age 32 years; 71% females) hospitalised for MDD in two psychiatric clinics in the city of Bogotá. The ICD-10 and DSM-IV-TR diagnostic criteria were used. Patients with an organic mental syndrome which might have explained the affective symptoms or with comorbidity with substance abuse or dependence, dementia, psychotic disorder or bipolar disorder were excluded.

- •

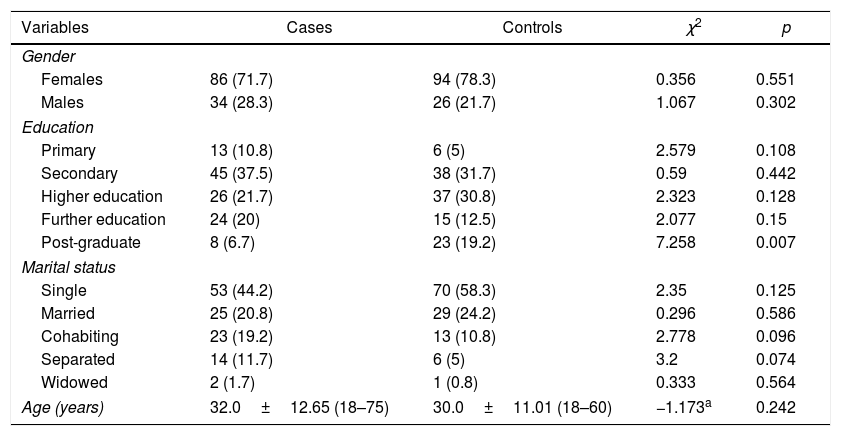

Control group of 120 people (mean age 30 years; 78% females) from an academic community and healthcare and administrative staff from mental health institutions. For this group, the presence of any mental disorder-related diagnosis was ruled out through the structured MINI interview as well as that they had no kinship with the patients. It should be mentioned that both groups were comparable according to sociodemographic variables (Table 1).

Table 1.Demographic variables of the case and control groups and differences between groups.

Variables Cases Controls χ2 p Gender Females 86 (71.7) 94 (78.3) 0.356 0.551 Males 34 (28.3) 26 (21.7) 1.067 0.302 Education Primary 13 (10.8) 6 (5) 2.579 0.108 Secondary 45 (37.5) 38 (31.7) 0.59 0.442 Higher education 26 (21.7) 37 (30.8) 2.323 0.128 Further education 24 (20) 15 (12.5) 2.077 0.15 Post-graduate 8 (6.7) 23 (19.2) 7.258 0.007 Marital status Single 53 (44.2) 70 (58.3) 2.35 0.125 Married 25 (20.8) 29 (24.2) 0.296 0.586 Cohabiting 23 (19.2) 13 (10.8) 2.778 0.096 Separated 14 (11.7) 6 (5) 3.2 0.074 Widowed 2 (1.7) 1 (0.8) 0.333 0.564 Age (years) 32.0±12.65 (18–75) 30.0±11.01 (18–60) −1.173a 0.242

The MINI is a structured diagnostic test that assesses DSM-IV and ICD-10 psychiatric disorders. The test takes approximately 15min to apply and its design enables it to be used as a structured psychiatric interview for clinical trials and epidemiological studies. The MINI is the reference standard for the study, because since its properties make it possible to confirm the participants’ mental health status it guarantees the diagnostic criteria of the entire sample.

Questionnaire on life eventsThe questionnaire contains a list of life events32 in order to assess their frequency and the degree of stress perceived with them in the last year. It measures the degree of stress on a scale of 0 (none) to 4 (a great deal). This instrument also provides information on the subjects’ rating of the events as positive/negative, expected/unexpected and controllable/uncontrollable. Reliability levels ranging from 0.68 to 0.83 were found.23,33

STDI state–trait depression questionnaire, Spanish adaptation of Spielberger et al.34This questionnaire is comprised of 20 items with two scales: Trait and State, each one with ten items, five for dysthymia and five for euthymia with multiple-choice answers (1, 2, 3 or 4). The euthymia items are defined as the inverse score. The reliability levels of the test reported by the authors are high, from 0.71 to 0.92 for the different scales in the general population. In Colombia, Cronbach's alpha from 0.71 to 0.86 is reported in the general population.35

ProcedureThe project was approved by the ethics committees of the participating institutions and an independent research ethics committee. Once the patients and the controls had signed the informed consent form, trained clinical psychologists carried out the MINI diagnostic interview to confirm the inclusion criteria and to apply the questionnaires. An identification code was assigned to each participant to guarantee data confidentiality. The patients were interviewed by a trained clinical psychologist after the most acute phase of their hospitalisation. It should be noted that 17.7% of the patients admitted with a diagnosis of MDD during the study period did not agree to participate or could not be interviewed as they were taking part in some activity planned by the institution or had already been discharged.

Statistical analysisThe data obtained from the participants was input into an SPSS database, coded to guarantee confidentiality, and data input was verified randomly. Only one missing data item per questionnaire was tolerated; however, the portion of missing data was not significant. The calculation of descriptive statistics and non-parametric comparison using the χ2 test for categorical variables and the Mann–Whitney U test for continuous variables was performed with the SPSS statistical package. To demonstrate the differentiation between the group of cases and the controls, in addition to the MINI interview, the negative affect component was analysed with the STDI scales by means of the non-parametric Mann–Whitney U test for the comparison of medians. A binary logistic regression analysis was performed to determine how predictive the stress variables were for MDD. The stress variables were categorised as dummy variables and the progressive stepwise method was used. This analysis was carried out with the R statistical package.

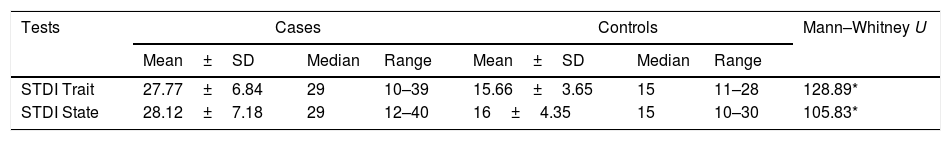

ResultsThe scores obtained in the depression negative affect tests (STDI) were higher in the case group than in the control group (Table 2), with statistically significant differences.

Descriptive statistics of the State–Trait Anxiety Inventory by study group and the difference between groups.

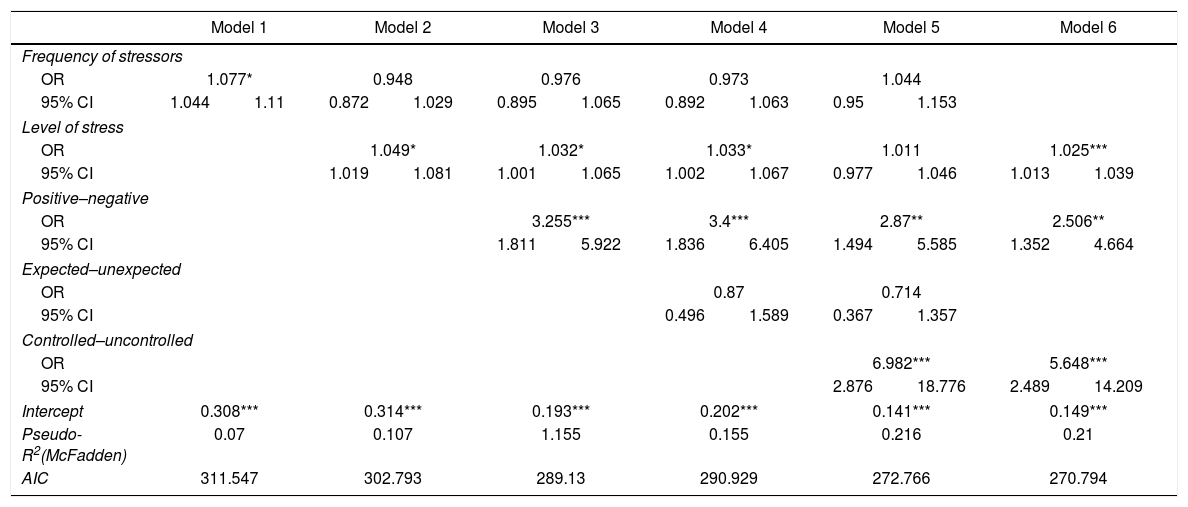

A binary logistic regression analysis was carried out, using the diagnosis of MDD as the dependent variable and the frequency of stressful events, the level of perceived stress and the positive-negative, controllable-uncontrollable and expected-unexpected appraisal as the predictor variables. These variables were included one by one in a stepwise progression method.

For the first step, model 1 was proposed, in which only the frequency of stressors was included as a predictor variable, and it explained 0.7% of the variance in the development of depression (p<0.05). In the next step, the level of stress variable was added, which increased the explanation of variance to 10%. It should be noted that the frequency of events lost statistical significance and only the level of stress variable presented predictive weight (model 2). For the third step, the positive-negative appraisal variable was included, which increased the explanation of variance by 15%, and only the two variables relating to level and appraisal of stress included in the model were found to be statistically significant (model 3). The expected-unexpected appraisal variable was then introduced (model 4), and variance did not change with regard to the immediately preceding one (15%). Neither did this variable present statistical significance. When the controllable-uncontrollable appraisal variable was introduced, variance increased by 21% and was statistically significant (model 5). It is interesting to note that the frequency of events variable and the perception of the event as expected–unexpected variable did not contribute significantly to the model. In view of this result, it was decided to evaluate one last model, taking the variables with the highest odds (stress level, positive–negative and controllable–uncontrollable appraisal), also establishing an explained variance of 21% (model 6). This model presented a lower Akaike index than the previously analysed models and was the most parsimonious model.

Table 3 shows the results of the regression. As the variables are entered, the percentage of explained variance increases and the residual variance and the Akaike index decrease.

Results of the binary logistic regression for depression.

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency of stressors | ||||||||||||

| OR | 1.077* | 0.948 | 0.976 | 0.973 | 1.044 | |||||||

| 95% CI | 1.044 | 1.11 | 0.872 | 1.029 | 0.895 | 1.065 | 0.892 | 1.063 | 0.95 | 1.153 | ||

| Level of stress | ||||||||||||

| OR | 1.049* | 1.032* | 1.033* | 1.011 | 1.025*** | |||||||

| 95% CI | 1.019 | 1.081 | 1.001 | 1.065 | 1.002 | 1.067 | 0.977 | 1.046 | 1.013 | 1.039 | ||

| Positive–negative | ||||||||||||

| OR | 3.255*** | 3.4*** | 2.87** | 2.506** | ||||||||

| 95% CI | 1.811 | 5.922 | 1.836 | 6.405 | 1.494 | 5.585 | 1.352 | 4.664 | ||||

| Expected–unexpected | ||||||||||||

| OR | 0.87 | 0.714 | ||||||||||

| 95% CI | 0.496 | 1.589 | 0.367 | 1.357 | ||||||||

| Controlled–uncontrolled | ||||||||||||

| OR | 6.982*** | 5.648*** | ||||||||||

| 95% CI | 2.876 | 18.776 | 2.489 | 14.209 | ||||||||

| Intercept | 0.308*** | 0.314*** | 0.193*** | 0.202*** | 0.141*** | 0.149*** | ||||||

| Pseudo-R2(McFadden) | 0.07 | 0.107 | 1.155 | 0.155 | 0.216 | 0.21 | ||||||

| AIC | 311.547 | 302.793 | 289.13 | 290.929 | 272.766 | 270.794 | ||||||

Our main objective is to establish whether or not the frequency of stressful life events and the appraisal of them is associated with MDD. The results showed that patients’ appraisal of stressful events carries greater weight than the number of events experienced. In relation to their appraisal of the event, the attribution of not controlling the event has greater predictive power, followed by its appraisal as negative. Moreover, the appraisal of an event as unexpected was clearly not associated with the disorder.

Our results are in line with the hypothesis considered regarding stressful life events in that they demonstrate that the clinical population reports a significantly higher perception of stress. This has been confirmed in previous studies, such as that by Mazurka et al.36, who reported that depressed patients have a greater number of events and a greater degree of stress. Similarly, in a Mexican population Veytia et al.33 demonstrated that stressful life events are related to depression symptoms.

However, the literature has also established a relationship between the appraisal of these stressful events and symptoms of MDD,16,18,27,29 which is confirmed by our findings, also in line with Abramson et al.26 in their attributional theory and the relationship they pose between this attributional style and the presence of depressive symptoms. Authors such as Noriega et al.24, Sanjuán and Magallares28 and Rietschel et al.37 suggest that a person's attribution or classification of a stressful event is more significant in predicting higher levels of depression than report of the event. The findings of the studies by Soria et al.30 and Sanjuán and Magallares29 show that the attribution of uncontrollability to stressful life events influences the presentation of states associated with MDD. Thus, the stressful events reported with a low perception of control and as negative provide a better explanation of the model. As Soria et al.30 assert, the attribution or explanation of negative life events as uncontrollable influences the generation of expectations of hopelessness, which could facilitate MDD. These findings are also consistent with the results of our study.

Authors such as Neupert et al.38 suggest that the greater the perception of control, the smaller the effect on physical and emotional well-being in response to stressful life events. The perception of control that a person may have in response to a series of life events is an important protective factor that the patients studied in this study seemed to lack. This corroborates the results, as it identifies the difference between having a low or a high perception of control.

Nevertheless, with regard to the finding that the appraisal of a stressful event as unexpected does not contribute, it might be mentioned that this variable has been associated with anxiety disorders in the literature.39,40 According to Havranek et al.,41 the lack of controllability and the unpredictability of events not only have separate effects, they also interact, in anxiety measurements in susceptible individuals and could provide information about the comorbidity between anxiety and depression.

One limitation of this study is that stressful life events were appraised by means of questionnaires about retrospective situations, which could prompt a memory bias. One of this study's particular strengths is that a hospitalised population of patients with MDD was used. However, this must also be considered when the results are interpreted, due to a possible overestimation of life events on account of clinical condition, with the presence of increased negative affect. To offset this bias, the questionnaires were applied after the initial period of hospitalisation, once the patients had been discharged from the acute care unit into the general hospital area. For future studies, this limitation could be better controlled by including a follow-up phase with a second application of the questionnaire at a post-discharge check-up appointment comparing the two sets of appraisals. This could rekindle the debate as to whether life events should be conceptualised as a characteristic of the person rather than of the environment, as proposed by Kasl.42 There is also a potential risk of selection bias among controls if individuals’ reasons for participating in the study were related to seeking help. This bias was reduced with the application of the MINI structured interview to rule out clinical symptoms. Finally, it is important to mention that all the psychologists who held the interview and applied the questionnaires knew which group each participant was from.

ConclusionsThe purpose of this study is to explain MDD, taking the attributional theory and the cognitive diathesis-stress model into account. Significant differences in the reporting of the frequency and intensity of stressful life events are consistent with these models. Our results on the predictive value of the variables studied confirm the importance of the appraisal of life events as predictors of MDD. Beyond the frequency of reported stressful events, patients diagnosed with MDD were seen to have a greater appraisal of lack of control over the situation compared to the general population without MDD. These results should be taken into account in the construction of intervention plans, emphasising the reappraisal of stressful life events. This is also an important aspect for the design of programmes for the prevention of depressive disorders and the promotion of mental health.

FundingThe data for this article were taken from a sub-sample of the “Perceived stress and genetic and epigenetic markers in major depressive disorder” project, funded by Colciencias (Application procedure 712 Basic Science: code 120471250970/contract 908-2015).

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

We would like to express our gratitude to the institutions that supported this project, to the research assistants and to the participants, who kindly shared their information.

Please cite this article as: Gómez Maquet Y, Ángel JD, Cañizares C, Lattig MC, Agudelo DM, Arenas Á, et al. El papel de la valoración de los sucesos vitales estresantes en el Trastorno Depresivo Mayor. Rev Colomb Psiquiatr. 2020;49:67–74.

Presented as a Free Paper at the 8th Congreso Nacional de Psicología [National Psychology Congress], held on 27, 28 and 29 July 2017.