The catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome (CAPS) accounts for less than 1% of patients with antiphospholipid syndrome (APS). Is its most serious manifestation and is characterized by microthrombotic events, positive serology and multiple organ failure.1,2

More than 60% of patients develop pulmonary complications such as acute respiratory distress syndrome and pulmonary thromboembolism, as well as affection of the central nervous system: hypertensive encephalopathy, cerebrovascular event and seizures. 50% have cutaneous manifestations.3,4 Several epidemiological studies report the finding of lupus anticoagulant and anticardiolipin antibodies in up to 80%, thrombocytopenia in 50% and hemolytic anemia in 30% of patients.5,6

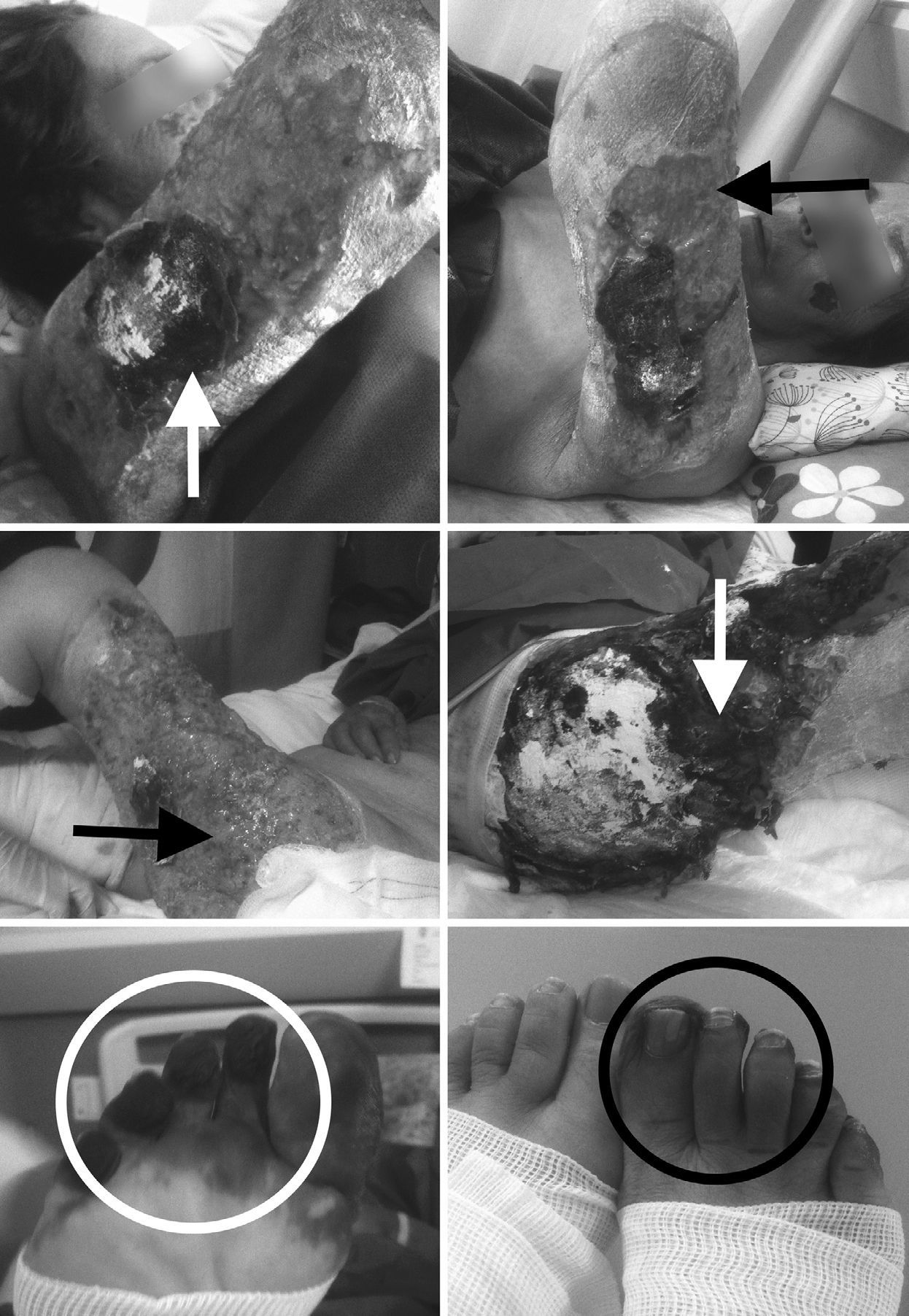

Here we present the case of a 64-year old woman who went to our hospital with symptoms of moderate and intermittent abdominal pain, which disappeared after admission. Urinary tract infection, appendicitis and cholecystitis were ruled out as likely causes. One day later she developed purpuric lesions in the auricular pavilions and cheeks, also affecting the left arm, the legs and the buttocks. All lesions progressed into ulcers and occupied 80% of the total body surface, in less than a week; subsequently she developed thrombosis in the fingers of the right lower limb with absence of distal pulses, pallor, paresthesia, cyanosis with sensory deficit and necrosis (Fig. 1). The Doppler ultrasound reported arterial occlusion. Positive lupus anticoagulant antibodies and anticardiolipin antibodies (IgG 46.2; IgM 77) were reported, along with non-leukocytoclastic chronic vasculitis of the capillaries of small and medium caliber of the papillary and reticular dermis in its superficial portion, in the biopsy of the lower extremities.

It was administered low molecular weight heparin, methylprednisolone and cyclophosphamide; and she also received 5 sessions of plasmapheresis. The patient developed multiple organ failure (hematologic, respiratory and renal) and died 8 weeks later.

If CAPS is one of the rarest manifestations of APS (the total number of cases reported by the European International CAPS Registry is 282), its presentation in people older than 60 years is even more rare: only 10% (29 cases).6–8 The definitive diagnosis requires the simultaneous presence of multiple organ failure, development of manifestations in less than a week, histopathological confirmation of thrombosis of small vessels, and the presence of antiphospholipid antibodies in two occasions with a difference of 12 weeks. The likely diagnosis is made in the absence of one of the 4 criteria above mentioned.5

The main cutaneous manifestations reported by the International Registry were livedo reticularis (43%), ulcers (12%), gangrene (5%), digital ischemia (4%), purpura (4%) and necrosis (3%).7 All these were developed in the presented case.

The first symptoms that appear are neurological in 12%, followed by renal (8%), dermatologic (7%), abdominal (6%) and acute respiratory distress syndrome (5%).6–8 The abdominal pain in this case had an inconstant evolution, it was studied and specific causes were ruled out.

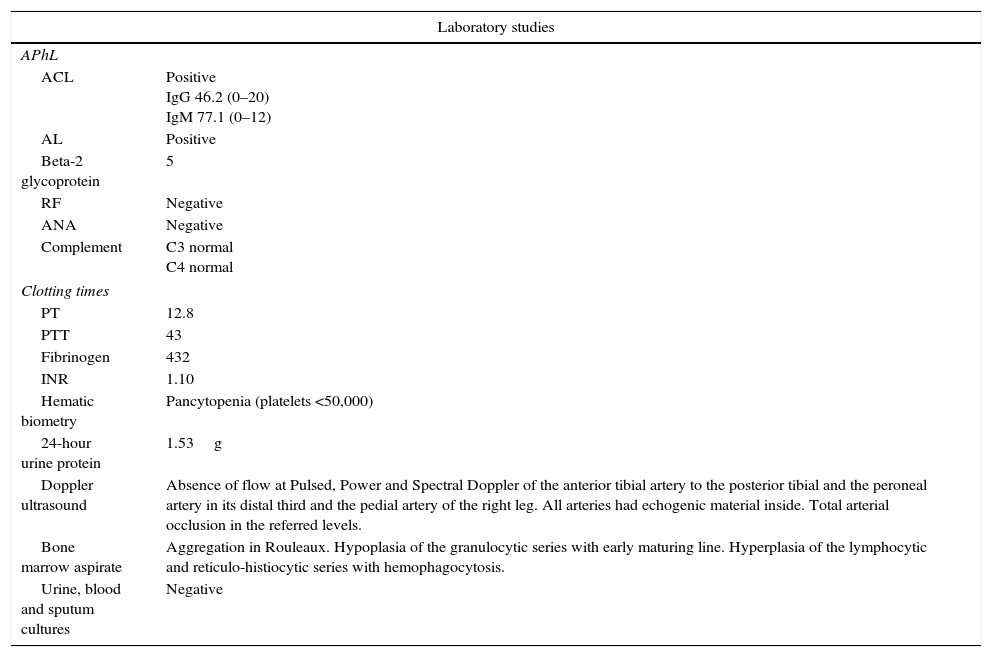

As in 44% of the registered cases, the patient had no previous diagnosis of APS. The percentage of obtained biopsies reported by the International Registry is low (14%) and only 12% of these were confirmatory.7,8 The biopsy of the case reported non-leukocytoclastic chronic vasculitis. The vasculitis was studied and an infectious cause was ruled out. She even received antibiotic empirically without improvement. The absence of conclusive characteristics could be due to the existing thrombocytopenia (Table 1). In this case and in those whose initial biopsies are not conclusive it is necessary to repeat biopsy.5,6 Due to the death of the patient it was not possible to obtain a second biopsy before the 12 weeks suggested.4 The same difficulty has been reported by the International Registry.7,8

Laboratory and imaging studies.

| Laboratory studies | |

|---|---|

| APhL | |

| ACL | Positive IgG 46.2 (0–20) IgM 77.1 (0–12) |

| AL | Positive |

| Beta-2 glycoprotein | 5 |

| RF | Negative |

| ANA | Negative |

| Complement | C3 normal C4 normal |

| Clotting times | |

| PT | 12.8 |

| PTT | 43 |

| Fibrinogen | 432 |

| INR | 1.10 |

| Hematic biometry | Pancytopenia (platelets <50,000) |

| 24-hour urine protein | 1.53g |

| Doppler ultrasound | Absence of flow at Pulsed, Power and Spectral Doppler of the anterior tibial artery to the posterior tibial and the peroneal artery in its distal third and the pedial artery of the right leg. All arteries had echogenic material inside. Total arterial occlusion in the referred levels. |

| Bone marrow aspirate | Aggregation in Rouleaux. Hypoplasia of the granulocytic series with early maturing line. Hyperplasia of the lymphocytic and reticulo-histiocytic series with hemophagocytosis. |

| Urine, blood and sputum cultures | Negative |

The first line therapeutic strategy is total anticoagulation and intravenous corticosteroids (methylprednisolone 1000mg/day)4; followed by plasmapheresis and immunoglobulin (0.4g/kg/day) and cyclophosphamide or rituximab.2,4

The mortality is high (50%), two-thirds of the mortality are due to pulmonary complications followed by infections such as pneumonia (14%). The renal failure in the patient precluded the performance of imaging studies confirmatory of life-threatening thrombotic complications.

The main finding at autopsies is microthrombosis.9,10

The case evidences the difficulty in the diagnosis of CAPS. According to the criteria of Asherson it is necessary a biopsy confirmatory of microthrombosis. We suggest that a negative report does not rule out the diagnosis. Given the poor prognosis of the CAPS is essential to maintain a high clinical suspicion in order to initiate timely treatment.

Please cite this article as: Asencio-del Real G, Díaz-Ramos JA, Leal-Mora D. Síndrome antifosfolípido catastrófico en el anciano: a propósito de un caso. Rev Colomb Reumatol. 2016;23:47–49.