Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is an autoimmune disorder characterized by protean clinical manifestations. Shrinking lung syndrome (SLS) is a rare pulmonary complication of this disease. It is characterized by progressive dyspnea, pleuritic chest pain, and decreased lung volume without signs of parenchymal disease. We report the observation of a 71-year-old patient with systemic lupus for 46 years, whose SLS is evoked by unexplained chronic dyspnea, convincing imaging, and respiratory functional exploration.

El lupus eritematoso sistémico es una enfermedad autoinmune clínicamente proteica. El síndrome del pulmón encogido o síndrome del pulmón pequeño es la manifestación más rara de esta enfermedad en los pulmones. Se caracteriza por disnea, dolor torácico pleurítico y disminución gradual del volumen pulmonar sin signos de enfermedad parenquimatosa. Se presenta el caso de una paciente de 71 años con lupus sistémico desde hace 46 años, cuyo síndrome del pulmón encogido (SPE) es evocado por disnea crónica inexplicable, imagenología convincente y exploración funcional respiratoria.

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is an autoimmune disease with very heterogeneous clinical expression.1 Respiratory involvement in this disease is common but less well known than skin, joint and kidney damage. Its prevalence according to the criteria used varies between 20 and 90%.2 Its diagnosis can be difficult because of its range of presentations, and the need to rule out an infectious or iatrogenic pathology beforehand in these patients who are often immunosuppressed.2 Lupus respiratory manifestations can be classified into five groups of attacks: pleural, pulmonary infiltrate, affecting airways, vascular and muscular.3 Shrinking lung syndrome (SLS) is a rare respiratory manifestation of lupus affecting less than 1% of patients.4 It is manifested clinically by progressive dyspnea associated with pleural chest pain, functionally by a restrictive syndrome, and morphologically by a unilateral or bilateral elevation of the diaphragm with a decrease in lung volumes in the absence of other parenchymal abnormalities.3 Its pathophysiology is still not known.5,6 However, several mechanisms have been put forward: micro atelectasis with surfactant deficiency, primary damage to the respiratory muscles, phrenic neuropathy, diaphragmatic fibrosis, pleural adhesions and pleural pain reducing thoracic expansion.7–12

The positive diagnosis of SLS is difficult, it must necessarily rule out other causes of pleuropulmonary involvement before it is made.3 In a recent review of the literature, only 170 cases of SLS have been reported to date.7 We add here the observation of our lupus patient with a typical SLS.

Case reportThis is a 71-year-old woman, hypertensive well controlled by Ramipril 5mg/day, followed since the age of 25 for systemic lupus. The diagnosis was made at the time by American college of rheumatology (ACR) criteria of 197113 with the presence of skin involvement, non-deforming peripheral polyarthritis and pleurisy. The clinical pattern was completed a few years later (1991) by hematological damage (thrombocytopenia) requiring the initiation of full-dose corticosteroid therapy and then reduction, associated with a synthetic antimalarial (Hydroxy chloroquine). The course was favorable with stable remission. After a long period of non-follow-up (30 years), during which the patient was only taking prednisone at 5mg/day, she consulted at our level because of a progressive worsening dyspnea which had set in during a year earlier, associated with a recurrent dry cough that did not respond to treatment by antibiotics and bronchodilators. She was also put on folic acid due to macrocytic anemia at 9g/dl. Her cardiac exploration showed no abnormalities.

The clinical examination on admission found a shortness of breath at slightest effort, with mucocutaneous pallor and mouth ulcers inside of the cheek. She had no arthralgia or arthritis, no jaundice, and no tumor or infectious syndrome.

Biologically there was a regenerative macrocytic anemia at 5g/dl (reticulocytes rate at 79,750/mm3), neutropenia at 1100/mm3, and thrombocytopenia at 20,000/mm3), hemolysis tests (haptoglobin, bilirubin, LDH) was without abnormality as well as the direct and indirect Coombs's test, the dosage of the antipernicious factors was normal, and the myelogram was without abnormality. The serum protein electrophoresis showed a chronic inflammatory reaction, the erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) was at 120mm with a C-reactive protein (CRP) at 4mg/l. The C3 and C4 fractions of the complement were decreased, the viral serologies HIV, HBV, HCV, SARS Cov2, CMV, EBV were negative. The hepatic, renal, thyroid and hemostasis tests were without abnormalities.

Immunological tests showed homogeneous ANA at 1/1000, anti-native DNA antibody at 254IU/ml (standards<30IU/ml) without specific target, presence of Prothrombin antibody, and absence of cardiolipin antibody, beta-2 glycoprotein 1 antibodies, intrinsic factor antibody, and parietal cells antibody.

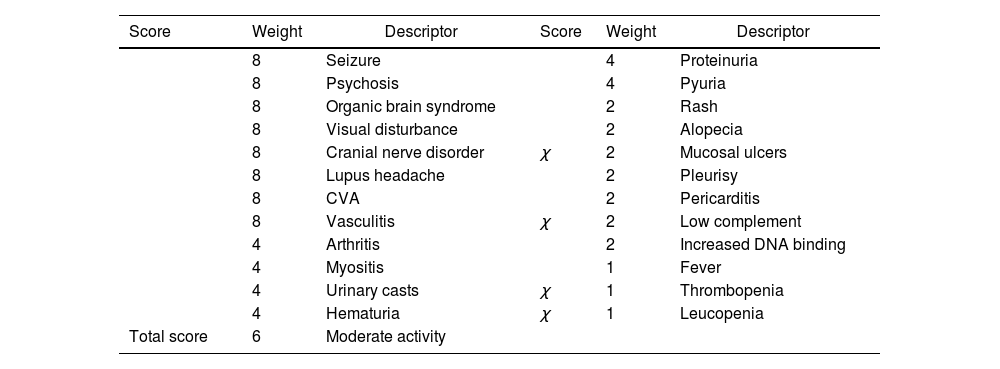

The SLEDAI-2K activity score of 6, was in favor of moderate activity (Table 1).14

SLEDAI-2K score (at admission).

| Score | Weight | Descriptor | Score | Weight | Descriptor |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8 | Seizure | 4 | Proteinuria | ||

| 8 | Psychosis | 4 | Pyuria | ||

| 8 | Organic brain syndrome | 2 | Rash | ||

| 8 | Visual disturbance | 2 | Alopecia | ||

| 8 | Cranial nerve disorder | χ | 2 | Mucosal ulcers | |

| 8 | Lupus headache | 2 | Pleurisy | ||

| 8 | CVA | 2 | Pericarditis | ||

| 8 | Vasculitis | χ | 2 | Low complement | |

| 4 | Arthritis | 2 | Increased DNA binding | ||

| 4 | Myositis | 1 | Fever | ||

| 4 | Urinary casts | χ | 1 | Thrombopenia | |

| 4 | Hematuria | χ | 1 | Leucopenia | |

| Total score | 6 | Moderate activity |

SLEDAI: Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Disease Activity Index.

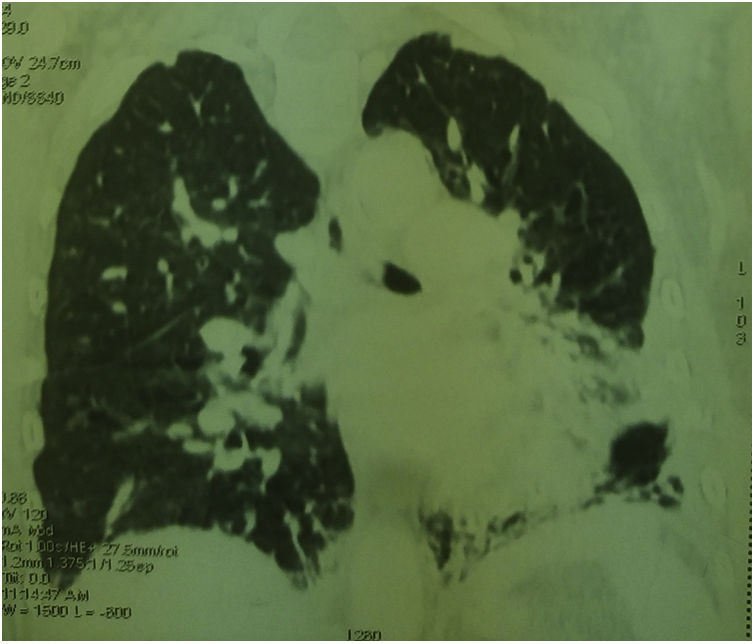

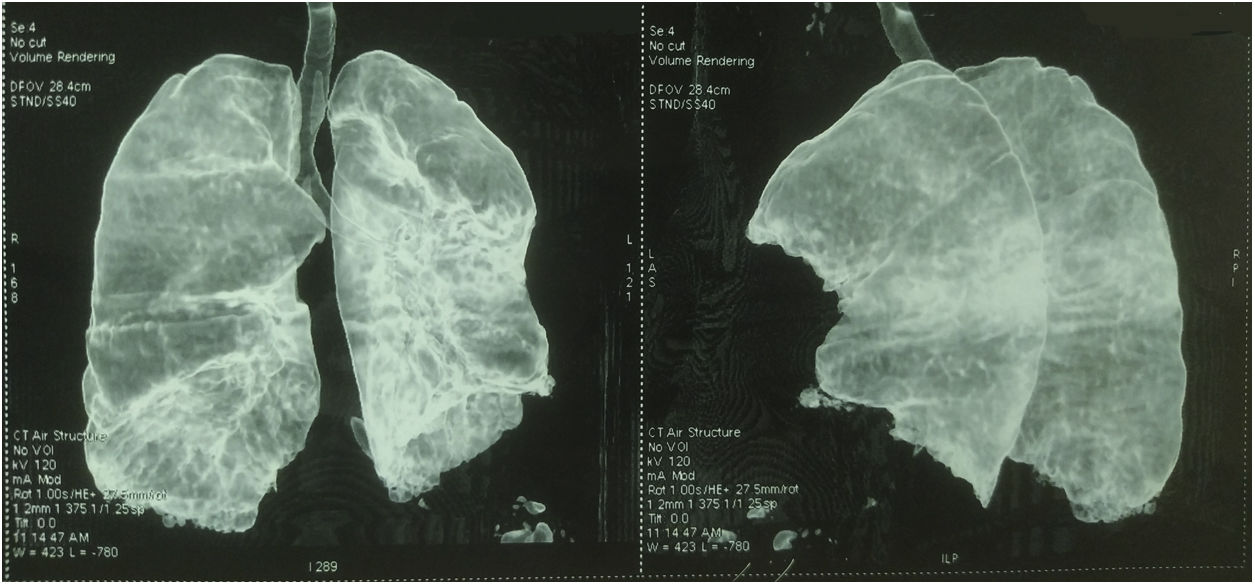

Thoracic CT angiography allowed us to eliminate a pulmonary embolism, and to objectify a diffuse bronchial syndrome in the form of regular circumferential bronchial wall thickening associated with sub-segmental atelectasis involving the internal segment of the middle lobe as well as the lower segment of the lingula, with ascension of the left diaphragmatic dome, without fibrosis (Figs. 1–3).

Pulmonary function tests (PFTs) showed a mixed pattern; non-reversible obstructive syndrome after inhalation of B2 agonist, and restrictive syndrome (FVC at 51%). The abdominal pelvic examination (ultrasound and CT) was without abnormality.

The diagnosis of a hematologic flare associated with patent pulmonary involvement of her lupus disease was made in our patient.

Evidence in favor of SLS was progressive dyspnea, ascension of the left diaphragmatic hemi-dome with basal band atelectasis and retracted appearance of the lung on chest CT, and restrictive syndrome on RFE. The non-reversible obstructive pulmonary involvement under bronchodilators with diffuse bronchial thickening on chest CT, and in the absence of smoking and atopy in our patient, suggests a priori a bronchial involvement of lupus.

From a therapeutic standpoint, we have instituted intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIg): 400mg/kg/day for 5 days followed by a relay with prednisone 1mg/kg/day, a synthetic antimalarial (Plaquenil®), and red blood cell transfusion in front of poorly tolerated deep anemia of inflammation. The outcome was favorable with an increase after one week of platelets>100,000/mm3, and improvement in hemoglobin which stabilized at 8.5g/dl after 4 weeks. The dyspnea improved markedly.

DiscussionShrinking lung syndrome is a rare manifestation of lupus.6 It was first described in 1965 by Hoffbrand and Beck.9 Since this discovery, only sporadic cases have been reported in the literature.15 According to certain cohorts, its prevalence remains very low, it affects less than 1% of lupus.4 The elements on which the diagnosis of SLS is made are progressive dyspnea often associated with pleural pain, unilateral or bilateral elevation of the diaphragm with a decrease in lung volumes in the absence of other parenchymal abnormalities, and finally a restrictive syndrome at PFTs. The exact mechanisms involved in the genesis of all these anomalies are still not well understood.7–12 In fact, the diagnosis of SLS can sometimes be difficult because it requires the elimination of other causes of pleuropulmonary involvement, namely interstitial, alveolar and vascular involvement.3,15 This can be responsible for both diagnostic and therapeutic delay. The observation we report is a good illustration of these difficulties, she did not consult at our level until after a year of developing dyspnea. To relate this dyspnea, which did not respond to symptomatic treatment, to SLS was not obvious in the foreground, in particular in front of the signs of hematological flare (especially anemia of inflammation). Nevertheless, the typical radiological lesions and the restrictive syndrome noted on PFTs, allowed us to retain this diagnosis after quickly eliminating the cardiac, parenchymal and vascular causes. This coexistence between the SLE flare and SLS in our patient is probably a coincidence. There does not appear to be a correlation between the presence of SLS and lupus flare.16 There are also no specific markers for SLS, some authors have suggested an association with Ro/SSA antibodies.6,17 For our patient, only the anti-native DNA antibody were high.

In addition, other respiratory lesions were observed in the patient. Diffuse bronchial thickening on CT with obstructive disorder on PFTs. This syndrome gives rise to several diagnoses. First, a long unrecognized bronchial asthma which was controlled by a daily oral intake of corticosteroid is mentioned. However, there is no notion of atopy in the patient and/or in her family and the non-reversible obstructive syndrome (gain of 130ml after taking a bronchodilator) does not meet the definition of asthma. Second, Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, which is unlikely given the absence of active and/or passive smoking as well as other contributing factors. Chest CT did not show bronchiectasis. In our opinion, this bronchial thickening is linked to lupus disease. Lower airway involvement in lupus is already described, but rare. In a cohort of 60 SLE patients, bronchial thickening and bronchiectasis were observed in 35% of cases.18

Currently, there is no specific treatment for SLS. However, some recommend treatment initially with corticosteroids between 0.5 and 1mgkg/day, either alone or in combination with immunosuppressive therapy such as cyclophosphamide, rituximab, azathioprine, hydroxychloroquine, methotrexate, mycophenolate mofetil or belimumab.15

Theophylline (750mg once daily) in one reported case improved total lung capacity by 31% with a probable effect on diaphragmatic contractility of respiratory muscles.19

Beta-agonists have also been beneficial in the treatment of SLS, Thompson et al. reported better exercise tolerance and a 58% increase in forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) after 12 days of treatment with 5mg nebulized albuterol six times per hour.20

The patient received full dose corticosteroid therapy to act on both hematologic impairment and SLS, combined with hydroxy chloroquine 400mg/day. She also had a B2 mimetic and an inhaled corticosteroid.

The clinical course after one month of treatment was favorable with marked improvement in dyspnea and hematimetric parameters. A check-up by PFTs is scheduled 3 months after treatment. This favorable prognosis, noted in the patient, is also reported in the various observations of SLS having had an appropriate treatment.15 In his review of the literature of 155 cases of SLS, Duron et al. reported clinical improvement in 94% of cases, functional improvement in 77% of cases and radiological improvement in 57% of cases after treatment.7 If steroid treatment is unsuccessful, rituximab may be an alternative.21–23 Other immunosuppressants (cyclophosphamide, azathioprine, hydroxy chloroquine, methotrexate, mycophenolate mofetil) have not been shown efficiency.24

The overall mortality seems low despite the lack of specific and standardized treatment.5

ConclusionSLS is a rare and little-known complication of systemic lupus. This respiratory syndrome is often revealed by unexplained progressive dyspnea. Chest imaging as well as respiratory function tests play a key role in the diagnosis which is often difficult. Appropriate treatment allows functional improvement and a reduction in morbidity and mortality. In the absence of guidelines and given the series of cases reported in the literature, corticosteroids associated with adjuvant treatment (inhaled beta-2 agonists) can be used as first-line treatment. If this fails, rituximab is the immunosuppressant of choice. However, further studies are needed to provide a more precise and standardized treatment strategy.

Ethical considerationsThe authors have the informed consent of the patients. The ethical committee of the Douera Hospital Center (Algiers, Algeria) approved the research.

FundingNone.

Conflict of interestNone.