The early identification of disorders of the musculoskeletal system in paediatrics should be of use in their approach and treatment. pGALS (paediatric Gait, Arms, Legs and Spine) is a tool used for evaluation of children with previous musculoskeletal disease. No studies were found in the literature reviewed that used pGALS as a screening test in Colombia.

ObjectiveTo identify the usefulness of pGALS as a screening test in children and adolescents in Colombia.

Materials and methodsDescriptive, cross-sectional study, which included children and adolescents, aged 6–16 years without a previous diagnosis of inflammatory or autoimmune skeletomuscular disease, who were evaluated with pGALS in their homes and in their schools during September and October 2018.

ResultsThe study included 169 patients, with a mean age of 9.43 years. Changes in pGALS were observed in 66.85% of the participants. The positive response to the first question in the examination had a sensitivity of 91.3%, a specificity of 53%, a positive likelihood ratio of 1.9, and negative likelihood ratio of 0.16 to identify changes in the musculoskeletal system. The positive response to any of the three questions had a statistically significant association to find altered pGALS (p = 0.001), sensitivity 58%, specificity 94%, positive likelihood ratio of 9.3, and negative likelihood ratio of 0.44. The acceptance by pGALS patients was 95.3%. The mean time to perform the test was 2:27 min.

ConclusionsPGALS is a quick and easy tool that is well tolerated by patients, and helps in the identification of musculoskeletal system disorders in the paediatric population.

La identificación temprana de trastornos del sistema musculoesquelético (SME) en pediatría permite realizar enfoque y tratamiento adecuado. pGALS (pediatric Gait, Arms, Legs and Spine) es una herramienta utilizada en la evaluación de niños con enfermedad osteomuscular previa. En la literatura revisada no se encontraron en Colombia estudios que apliquen pGALS como prueba de tamizaje.

ObjetivosIdentificar la utilidad de pGALS como prueba de tamizaje en niños y adolescentes en Colombia.

Materiales y métodosEstudio descriptivo, de corte transversal, que incluyó niños y adolescentes de 6 a 16 años sin diagnóstico previo de enfermedad osteomuscular de etiología inflamatoria o autoinmune, a quienes se evaluó con pGALS en sus viviendas y sus colegios durante septiembre y octubre de 2018.

ResultadosSe incluyeron 169 pacientes, edad promedio de 9,43 años. Se encontraron alteraciones en pGALS en el 66,85% de los participantes. La respuesta positiva a la primera pregunta de la exploración tuvo una sensibilidad del 91,3%, una especificidad del 53%, una razón de verosimilitud positiva de 1,9 y una razón de verosimilitud negativa de 0,16 para identificar alteraciones en el SME. La respuesta positiva a cualquiera de las tres preguntas tuvo asociación estadísticamente significativa para encontrar pGALS alterado (p = 0,001), sensibilidad 58%, especificidad 94%, razón de verosimilitud positiva de 9,3 y razón de verosimilitud negativa de 0,44. La aceptación de los pacientes de pGALS fue del 95,3%. El tiempo promedio en el que se realizó la prueba fue de 2:27 min.

ConclusionesPGALS es una herramienta de aplicación rápida y fácil, bien tolerada por los pacientes y que permite identificar trastornos del SME en la población pediátrica.

Pain is the most frequent symptom in musculoskeletal disorders (MSD). It is frequently identified in pediatrics and is a usual cause for visits to the doctor. The etiology of musculoskeletal disorders is mostly benign, and in some cases is a life-threatening manifestation,1 although the absence of pain does not rule out the presence of musculoskeletal disorders.2

Goff et al.3 showed that based on pediatric medical records, about two thirds of the cases of musculoskeletal disorders are missed. The assessment of MSD in children requires the ability to complete an adequate medical record, including a comprehensive physical examination, knowledge about the child’s normal development and its variations based on age, as well as about the epidemiology of the different pathologies by age group, in order to determine the diagnostic and therapeutic approach.

Foster et al.4 validated pGALS (pediatric Gait, Arms, Legs and Spine) for the assessment of school children with a diagnosis of juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA). The tool was found to be easy and quick to administer, it was accepted by parents/caregivers and children, with a sensitivity of 97–100 % and a specificity of 98–100%, for the detection of joint disorders.

pGALS has been used in the identification of MSD by various authors and in different populations.5–7

Whereas MSDs are a frequent cause of visits to the pediatrician, a quick, friendly tool that is well accepted by the patient and his/her parents is required. pGALS is suggested as a screening tool, though no similar studies were identified for Colombia in the literature reviewed.

MethodologyDescriptive, cross-section study intended to determine the value of pGALS as a screening tool in children and adolescents. The study included 169 patients between 6 and 16 years old, residents of Pasto (Colombia), examined at home and in two schools during September and October 2018. The sample size was based on convenience sampling.

The inclusion criteria were: age between 6 and 16 years, submitting an informed consent signed by their parents, and the child’s acceptance. Children with physical limitations to take the test were excluded.

The test was administered by a physician specializing in pediatrics, previously trained on pGALS by the department of pediatric rheumatology.

The information was collected in a single form specially designed for the trial. The demographic variables included gender and age. All of the participants received the three questions and underwent the 17 maneuvers comprised in the pGALS test, as described hereunder.

Questions- 1

Do you experience any pain or stiffness in the joints, muscles or back?

- 2

Do you have any difficulties to get dressed without any help?

- 3

Do you have any problems to walk up or down the stairs?

- 1

Watch the child standing up (front, back, sideways).

- 2

Bend down and touch toes.

- 3

Watch the child walking.

- 4

Heel and tiptoe walking.

- 5

Stretching hands upwards.

- 6

Look at the ceiling.

- 7

Placing hands behind the neck.

- 8

Bringing the ear against the shoulder (avoid raising the shoulder).

- 9

Open mouth widely and place three fingers inside.

- 10

Bring hands together palm against palm and then back to back.

- 11

Squeeze the joints between the metacarpals and phalanges.

- 12

Stretch hands in front.

- 13

Place hands in supine position and make a fist.

- 14

Bring thumb together with the tip of the fingers.

- 15

Palpate the knee to identify any effusions/pain.

- 16

Active knee motion (flexion and extension).

- 17

Passive hip motion (knee flexed at 90 degrees and internal hip rotation).

The time to administer the test was recorded. All patients in whom alterations were identified during the test were referred to pediatrics, orthopedics, physiatry or pediatric rheumatology. A scale from to 1 to 5 was used to measure the test acceptance by children, with 1 being not annoying and 5 very annoying, No pictures were taken of the children participating in the study.

The statistical analysis was based on descriptive and inferred statistical techniques, using the SPSS version 2.2. software. Frequency analysis was conducted for all variables. The comparative analysis of the categorical variables (answers to the first questions on the test and identification of test alteration) was performed using the chi square test, with a significance value of p < 0.05. Then, a bivariate analysis was conducted based on contingency tables to estimate the sensitivity, the specificity and likelihood ratios.

ResultsA total of 169 children were assessed, between 6 and 16 years old. The mean age was 9.43 years (standard deviation 2.43 years, median 9 years), 95 examined (56.2%) were males.

The test was completed in all the children; the mean time to administer the test was 2:27 min (range 1:51–3:55 min; median 2:25 min), 66 subjects (39.1%) said they experienced pain or stiffness of the joints, muscles or back; 4 (2.4%) had difficulty to get dressed without help and 7 (4.1%), experienced problems to walk up and down the stairs.

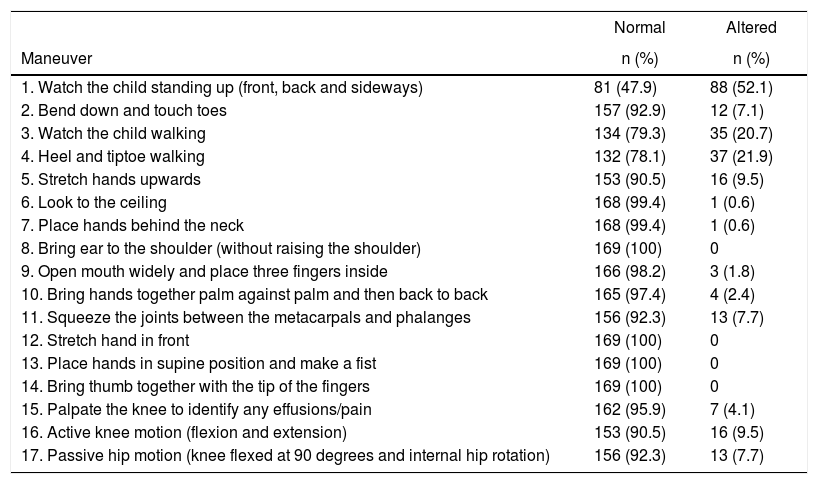

88 children (52.1%) experienced difficulty with maneuver number 1, which was the one with the highest frequency of difficulty, followed by maneuvers 4 (21.9%), 3 (20.7%), 5 and 16 (9.5%, respectively) (Table 1).

Frequency of alterations identified with pGALS in children and adolescents in Colombia.

| Normal | Altered | |

|---|---|---|

| Maneuver | n (%) | n (%) |

| 1. Watch the child standing up (front, back and sideways) | 81 (47.9) | 88 (52.1) |

| 2. Bend down and touch toes | 157 (92.9) | 12 (7.1) |

| 3. Watch the child walking | 134 (79.3) | 35 (20.7) |

| 4. Heel and tiptoe walking | 132 (78.1) | 37 (21.9) |

| 5. Stretch hands upwards | 153 (90.5) | 16 (9.5) |

| 6. Look to the ceiling | 168 (99.4) | 1 (0.6) |

| 7. Place hands behind the neck | 168 (99.4) | 1 (0.6) |

| 8. Bring ear to the shoulder (without raising the shoulder) | 169 (100) | 0 |

| 9. Open mouth widely and place three fingers inside | 166 (98.2) | 3 (1.8) |

| 10. Bring hands together palm against palm and then back to back | 165 (97.4) | 4 (2.4) |

| 11. Squeeze the joints between the metacarpals and phalanges | 156 (92.3) | 13 (7.7) |

| 12. Stretch hand in front | 169 (100) | 0 |

| 13. Place hands in supine position and make a fist | 169 (100) | 0 |

| 14. Bring thumb together with the tip of the fingers | 169 (100) | 0 |

| 15. Palpate the knee to identify any effusions/pain | 162 (95.9) | 7 (4.1) |

| 16. Active knee motion (flexion and extension) | 153 (90.5) | 16 (9.5) |

| 17. Passive hip motion (knee flexed at 90 degrees and internal hip rotation) | 156 (92.3) | 13 (7.7) |

Alterations were identified in 113 children and these were in order of frequency as follows: shoulder asymmetry (69%), articular hypermobility (16%), internal tibial torsion (13%), alterations of the grasping mechanics (8%), genu valgus (7%), knee arthralgia (5%), metatarsalgia (4,4%), polyarthralgia (4,4%),external tibial torsion (3.5%), talalgia (2.6%) and hamstrings bursitis (1.7%). A history of minor trauma before the test (3.5%), fracture or sprain (2.6%), and correction of equinovarus foot deformity (17%).

Finally, 111 (65.7%) of the children had to be referred to specialists for additional assessment of the alterations identified during the administration of the test; of these, 65 answered “yes” to one or more of the questions and 46 answered “no” to the three questions. Two children were referred to general medicine due to the identification of an incipient shoulder asymmetry.

An affirmative answer to question 1 “Do you experience any pain or stiffness in the joints, muscles or back?” had a statistically significant relationship with the need to refer the patient for further assessment (p = 0.001), with a sensitivity of 91.3%, specificity of 53%, positive likelihood ratio of 1.9 and negative likelihood ratio of 0.16 to identify any MSDs. An affirmative answer to any of the three questions had a statistically significant association with an altered pGALS (p = 0.001), sensitivity of 58%, specificity of 94%, positive likelihood ratio of 9.3 and negative likelihood ratio of 0.44.

With regards to tolerance and test acceptance, 161 (95.3%) children said it was not annoying, 4 (2.4%) said a bit annoying, 3 (1.8%) annoying, and one (06%) said it was very annoying.

DiscussionThere were 169 children assessed in the study, between the ages of 6 and 16 years old; all of them completed the test, and MSDs were identified in 65.7% of the children There were MSDs in 46 subjects who answered “no” to the three questions, which supports the idea that a negative answer to those questions does not rule out MSD and therefore, the complete test should be administered.1

In this study, a positive answer to the first question had a sensitivity of 91.3%, a specificity of 53%, a positive likelihood ratio of 1.9, and a negative likelihood ratio of 0.16 to identify MSD. Similarly, a positive answer to any of the three questions had a statistically significant relationship with an altered pGALS (p = 0.001), with a sensitivity of 58%, specificity of 94%, positive likelihood ratio of 9.3 and negative likelihood ratio of 0.44.

The results are similar to those reported in 2016 by Batu et al.5, after assessing 95 patients in the pediatric emergency department of Haccettepe University, and outpatients of the Department of Rehabilitation and Physical Therapy of the University of Marmara; they found a sensitivity of 64.7% and a specificity of 89.7% to identify one abnormal pGALS test, when there was a positive answer to one or more of the screening questions. Moreover, Smith et al.6 assessed pGALS in 51 children in a hospital and emergency setting, aged 4–16 years old; in this series, the sensitivity was 57% and the specificity was 63% for the diagnosis of MSD.

In Latin America, specifically in Peru, the Abernethy8 group administered the Spanish version of pGALS to 53 children between 4 and 16 years old, in the emergency department. A positive answer to one of more screening questions had a sensitivity of 63.6% and a specificity of 87.1% to identify alterations in pGALS. In Mexico, pGALS was used in children between 6 and 16 years old, 87 patients with osteomuscular disease versus 88 controls, with a 97% sensitivity, 93% specificity, positive likelihood ratio of 14.3 for the diagnosis of MSD.9

It should be noted that the studies conducted in Turkey, Malawi, Peru and Mexico were in children with previous MSDs, both inpatients as well as outpatients. This study focused on outpatients without a diagnosis of inflammatory or autoimmune MSD.

In India, pGALS was administered for screening MSD in school children between 3 and 12 years old. MSDs were identified in 368 (10.63%) of the participants, among which 366 (99.46%) answered “yes” to one or more of the screening questions and 223 (60.6%) had an abnormal pGALS test. Hypermobility (25.54%), growing pains (38.86%), and mechanical pains (24.46%) were the most frequent conditions. In this study, the frequency of MSDs was 67.5%, with shoulder asymmetry as the most frequent finding (69%), followed by articular hypermobility (15%).

pGALS acceptance by patients was 95.3%, similar to the figures reported by other authors. The mean time to administer the test in this study was 2:27 min, which is also similar to the data reported in the literature.

There are limitations because this is a descriptive trial, and the observation was the responsibility of only one examiner previously trained in pGALS by a pediatric rheumatologist; however, a concordance trial is required to be able to measure inter and intra-observer variability.

ConclusionspGALS is an easy to administer tool, it is quick, well accepted by patients, which allows for the identification of MSDs in the pediatric population, enabling timely diagnosis and therapeutic approaches. It may be administered by the general practitioner, by the pediatrician, or by a pediatric rheumatologist. The suggestion is to include this tool in routine pediatric assessment.

Ethical responsibilitiesProtection of persons and animals: the authors claim they have not conducted any experiments in humans or animals for this study.

Confidentiality of the information: the authors declare that no information from the participants in the study has been disclosed in this study.

Right to privacy and informed consent: the authors declare that this article does not disclose any patient data and all the participants submitted their informed consent signed by their parents and the children approval before participating in the study.

FinancingThe study was conducted with the author’s resources.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interest to disclose.

To the parents and children for participating in this study; to the Institución Educativa Municipal INEM in Pasto city for encouraging research at their institution.

Please cite this article as: Cárdenas Silva AM, Rodríguez Perea LM, Avendaño Valdés K, Cuellar Zapata N, Valencia AM, Gómez Mora MdP. Utilidad de pGALS como prueba de tamizaje en niños y adolescentes en Colombia. Rev Colomb Reumatol. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rcreu.2020.04.005

This was a work that won second place in the IX National Prize for Research in Rheumatology, Pediatrics category. Competition held within the framework of the XVII Colombian Congress of Rheumatology and VIII Colombian Congress of Pediatric Rheumatology, held in Barranquilla, Colombia, from 6 to 9 February. 2020;27:161–165.