Vasculitis is a heterogeneous group of diseases characterized by inflammation of the blood vessel wall, which can cause thrombosis, stenosis, or occlusion. Its pharmacological management involves corticosteroids and conventional and biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs.

ObjectivesThe objective was to determine the different types of systemic vasculitis and their pharmacological treatment in a group of patients from Colombia, 2019–2020.

Materials and methodsThis was a cross-sectional study that identified different types of systemic vasculitis and their pharmacological management in a group of patients from a drug-dispensing database of approximately 8.5 million people. Sociodemographic, comorbidity and pharmacological variables were considered. A descriptive analysis was performed.

ResultsA total of 621 patients with a diagnosis of systemic vasculitis were identified. The patients had a median age of 55.0 years, and 74.4% were women. The most common vasculitis types were those limited to the skin (30.1%), granulomatosis with polyangiitis (17.6%), and necrotizing vasculopathy (10.8%). A total of 81.0% of cases received corticosteroid prescriptions, 44.0% received azathioprine, and 24.0% received methotrexate; only 1.6% were prescribed biological antirheumatic drugs. Cardiovascular diseases were the most common comorbidity.

ConclusionsThe pattern of prescription medications used for patients diagnosed with systemic vasculitis is heterogeneous. Much of this population has associated comorbidities, which increases the use of medications according to the current management guidelines.

Las vasculitis son un grupo heterogéneo de enfermedades caracterizadas por la inflamación de la pared de los vasos sanguíneos, lo cual puede llegar a ocasionar trombosis, estenosis u oclusión. Su manejo farmacológico incluye corticoesteroides, antirreumáticos modificadores de enfermedad convencionales y biológicos.

ObjetivosEl objetivo de este estudio fue determinar los diferentes tipos de vasculitis sistémicas y su tratamiento farmacológico en un grupo de pacientes de Colombia.

Materiales y métodosSe trató de un estudio de corte transversal que identificó los diferentes tipos de vasculitis sistémicas y su manejo farmacológico en un grupo de pacientes, a partir de una base de datos de dispensación de medicamentos de aproximadamente 8,5 millones de personas. Se consideraron variables sociodemográficas, comorbilidades y variables farmacológicas, y se hizo un análisis descriptivo.

ResultadosSe identificaron 621 pacientes con diagnóstico de vasculitis sistémicas, con una mediana de edad de 55,0 años, el 74,4% mujeres, siendo las vasculitis más frecuentes las limitadas a la piel (30,1%), la granulomatosis con poliangeitis (17,6%) y la vasculopatía necrosante (10,8%). El 81,0% de los casos recibió corticoesteroides, el 44,0% azatioprina y el 24,0 metotrexate, mientras que solo el 1,6% tenía prescritos antirreumáticos biológicos. Las comorbilidades cardiovasculares fueron las más comunes.

ConclusionesEl patrón de prescripción de medicamentos utilizados en pacientes con diagnóstico de vasculitis sistémicas es heterogéneo y acorde con las guías actuales de manejo. Gran parte de esta población cursa con comorbilidades asociadas, lo cual incrementa el uso de medicamentos.

Vasculitis refers to a group of heterogeneous diseases characterized by inflammation of the blood vessel wall, which can cause thrombosis, stenosis or occlusion, leading to organ ischemia and even the formation of aneurysms or hemorrhages.1 This syndrome can affect both arteries and veins and can individual organs or manifest as a multisystemic disease, which is why a wide variety of clinical and pathophysiological findings is observed.2

Vasculitis can be divided into two broad categories according to its etiology: primary and secondary vasculitis. In the latter, the clinical picture is due to a known underlying cause; in contrast, in primary vasculitis, the etiology is primarily idiopathic.3,4 The most commonly used classification was defined in the Chapel Hill Consensus of 2012, which defined three large groups according to the caliber of the affected vessels: small (less than macroscopic size: arterioles, capillaries and venules), medium (vessels are smaller than the branches of the aorta but still have intima, elastic lamina, tunica media, and adventitia) and large vessels (the aorta and its main branches).5 Each of these groups is characterized by a specific clinical and histopathological presentation and a different therapeutic behavior.6

The distribution of this syndrome is particularly heterogeneous, and its prevalence and incidence tend to vary depending on geographical area, ethnicity and environmental factors.7 Although the epidemiology of these diseases is becoming better known, there is still a large gap in knowledge due to their low prevalence; however, the average incidence of primary vasculitis has been established in some studies to be between 13.1 and 20 cases per million inhabitants.8–10

Pharmacological therapy for systemic vasculitis consists of two clearly established phases; from induction to remission and maintenance, the mainstay of treatment is corticosteroids, and depending on the patient's attenuating conditions or the severity of the clinical presentation, other drugs are used, including cyclophosphamide, azathioprine, methotrexate and certain biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDS), such as rituximab and tocilizumab.11 In Colombia, there are few published studies on patients diagnosed with vasculitis8,12; the available studies generally involve a limited number of cases12 and do not provide a broad pharmacological characterization. Consequently, the present study has the objective of determining the types of systemic vasculitis and their pharmacological treatment in a group of patients from Colombia.

Materials and methodsA cross-sectional study of the patterns of prescription medications used to treat patients diagnosed with systemic vasculitis was conducted based on a drug-dispensing database that includes information from approximately 8.5 million people affiliated with the Colombian Healthcare System covered by six health insurance companies. The database covers approximately 30.0% of the active affiliated population under the contributory or paid regime and 6.0% of those under the government-subsidized regime, comprising 17.3% of the Colombian population.

Patients were identified using International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10) codes during the period from January 1, 2019, to June 30, 2020. Patients aged 14 years or older of any gender who were treated in an outpatient setting and undergoing pharmacological management for systemic vasculitis were included. According to the ICD-10 codes related to systemic vasculitis, the diagnoses were classified into the following groups:

- a.

Large vessel vasculitis: aortic arch syndrome [Takayasu] (M314), giant cell arteritis (M315, M316), cerebral arteritis (I677, I682), unspecified arteritis (I776).

- b.

Medium vessel vasculitis: polyarteritis nodosa (M300, M30, M30X, M308), mucocutaneous lymph node syndrome [Kawasaki].

- c.

Small vessel vasculitis: Wegener's granulomatosis (M313), polyarteritis with lung involvement [Churg-Strauss] (M301), cryoglobulinemia (D891), microscopic polyangiitis (M317).

- d.

Variable vessel vasculitis: Behcet's disease (M352), thromboangiitis obliterans [Buerger] (I73, I731).

- e.

Vasculitis limited to the skin (L958, L959).

- f.

Necrotizing vasculopathies (M318, M319).

- g.

Others: livedoid vasculitis (L950, L95, L95X), juvenile polyarteritis (M302), hypersensitivity angiitis (M310, M31, M31X).

Based on the medication use information for the affiliated population, which was systematically obtained by the drug-dispensing company (Audifarma S.A.), a database was designed that allowed the collection of the following patient variables:

- 1.

Sociodemographic: sex, age (under 40 years, from 41 to 64 years and 65 years or older), city of dispensation.

- 2.

Comorbidities: The main cardiovascular, endocrine, rheumatic, urologic, renal, psychiatric, neurological, digestive, respiratory and neoplastic diseases and those related to infections were identified based on ICD-10 codes.

- 3.

Medications for the management of vasculitis:

- •

Corticosteroids: prednisolone, prednisone, deflazacort, methylprednisolone, dexamethasone, betamethasone.

- •

Synthetic DMARDs: methotrexate, azathioprine, leflunomide, chloroquine, hydroxychloroquine, sulfasalazine.

- •

Immunosuppressants: cyclophosphamide, cyclosporine, mycophenolate, tacrolimus.

- •

Biological DMARDs: tocilizumab, rituximab, abatacept, ustekinumab, infliximab, etanercept, adalimumab.

- •

Others: colchicine.

- •

- 4.

Comedications: These were grouped into the following categories: (a) antidiabetic drugs (oral and subcutaneous), (b) blood pressure drugs and diuretics, (c) lipid-lowering drugs, (d) antiulcer drugs, (e) antidepressants, (f) anxiolytics and hypnotics (benzodiazepines and Z drugs), (g) thyroid hormone, (h) antipsychotics (typical and atypical), (i) antiepileptics, (j) antiarrhythmics, (k) antihistamines, (l) antidementia drugs, (m) opioid analgesics, (n) nonopioid analgesics, (o) bronchodilators and inhaled corticosteroids, (p) antiplatelet drugs, (q) anticoagulants.

The protocol was approved by the Bioethics Committee of the Technological University of Pereira under the category of “research without risk” (approval number 01-210920). The principles established by the Declaration of Helsinki were upheld.

The data were recorded in a Microsoft Excel database and subsequently analyzed using the statistical package SPSS Statistics, version 26.0 for Windows (IBM, USA). A descriptive analysis was performed using frequencies and proportions for the qualitative variables and measures of central tendency and dispersion for the quantitative variables according to their parametric behavior, which was established by the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test.

ResultsA total of 621 patients who were diagnosed with systemic vasculitis and related disorders and were receiving some pharmacological treatment were distributed in 56 different cities or municipalities. A total of 80.2% of the patients were found in 8 cities (Bogotá, Cali, Medellín, Pereira, Barranquilla, Manizales, Cartagena and Montería). A total of 74.4% (n=462) were women. The median age was 55.0 years (interquartile range 41.5–65.6 years): 22.7% (n=141) were younger than 40 years, 50.9% (n=316) were between 40 and 64 years, and 26.4% (n=164) were 65 or older. The vast majority were affiliated with the contributory regime (n=619; 99.7%).

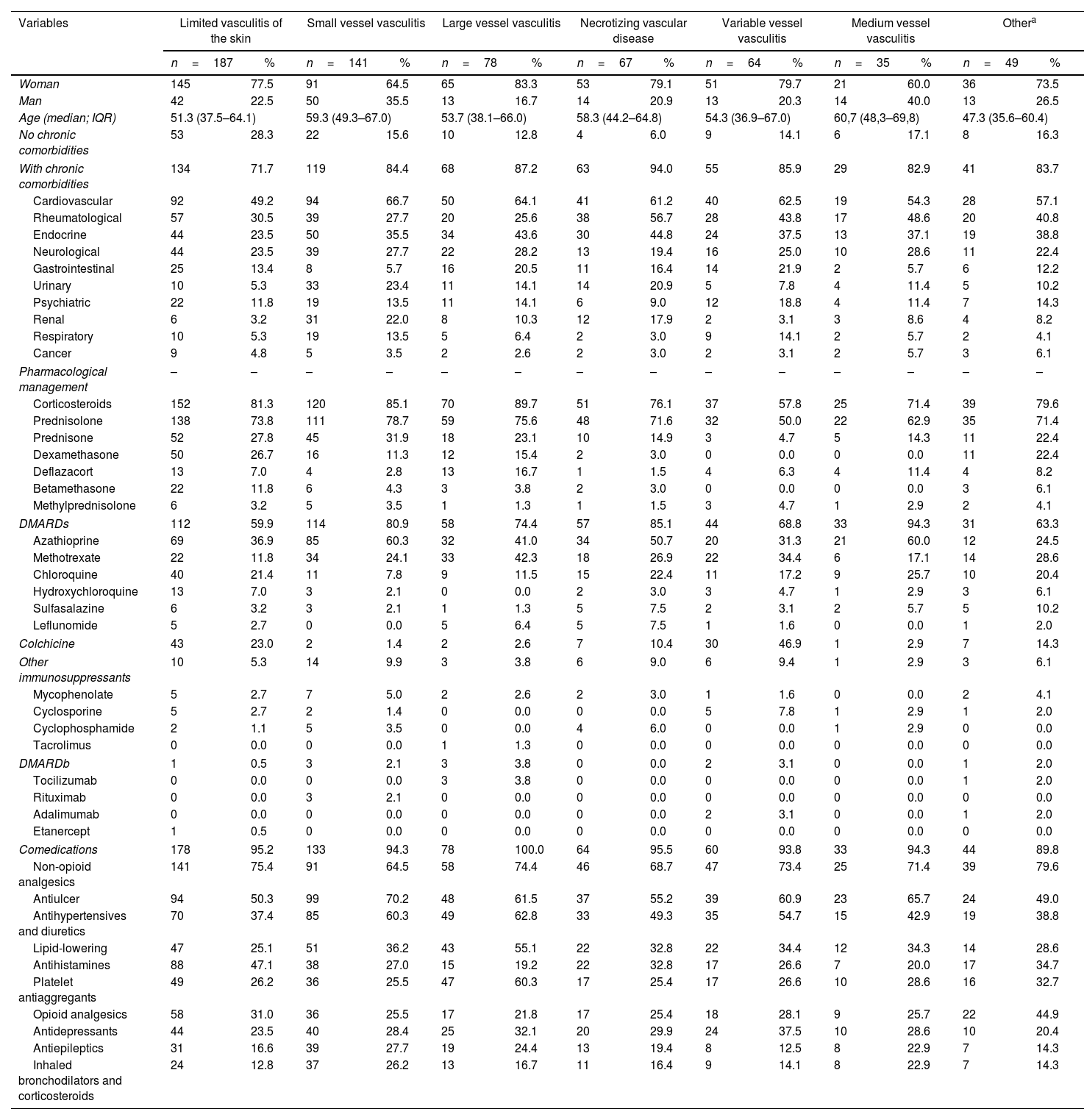

Concomitant chronic diseases were found in 82.0% (n=509) of the patients, of whom 47.2% (n=240) presented with 1 or 2 comorbidities, 33.2% (n=169) presented with 3 or 4 comorbidities, and 19.6% (n=100) presented with 5 or more simultaneous diseases. The 10 most frequently identified comorbidities were arterial hypertension (n=355; 57.2%), rheumatoid arthritis (n=98; 15.8%), hypothyroidism (n=92; 14.8%), diabetes mellitus (n=77; 12.4%), chronic kidney disease (n=63; 10.1%), Sjögren's syndrome (n=62; 10.0%), peripheral neuropathy (n=62; 10.0%), migraine (n=54; 8.7%), systemic lupus erythematosus (n=51; 8.2%) and osteoarthrosis (n=50; 8.1%). The most common were cardiovascular diseases (n=364; 58.6%), followed by rheumatological (n=219; 35.3%), endocrine (n=214; 34.5%) and neurological diseases (n=155; 25.0%) (Table 1). A total of 34.3% of the patients (n=213) had some infection during the study period.

Comparison of some sociodemographic, clinical and pharmacological variables with the diagnoses of systemic vasculitis, in a population of Colombia, 2019–2020.

| Variables | Limited vasculitis of the skin | Small vessel vasculitis | Large vessel vasculitis | Necrotizing vascular disease | Variable vessel vasculitis | Medium vessel vasculitis | Othera | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n=187 | % | n=141 | % | n=78 | % | n=67 | % | n=64 | % | n=35 | % | n=49 | % | |

| Woman | 145 | 77.5 | 91 | 64.5 | 65 | 83.3 | 53 | 79.1 | 51 | 79.7 | 21 | 60.0 | 36 | 73.5 |

| Man | 42 | 22.5 | 50 | 35.5 | 13 | 16.7 | 14 | 20.9 | 13 | 20.3 | 14 | 40.0 | 13 | 26.5 |

| Age (median; IQR) | 51.3 (37.5–64.1) | 59.3 (49.3–67.0) | 53.7 (38.1–66.0) | 58.3 (44.2–64.8) | 54.3 (36.9–67.0) | 60,7 (48,3–69,8) | 47.3 (35.6–60.4) | |||||||

| No chronic comorbidities | 53 | 28.3 | 22 | 15.6 | 10 | 12.8 | 4 | 6.0 | 9 | 14.1 | 6 | 17.1 | 8 | 16.3 |

| With chronic comorbidities | 134 | 71.7 | 119 | 84.4 | 68 | 87.2 | 63 | 94.0 | 55 | 85.9 | 29 | 82.9 | 41 | 83.7 |

| Cardiovascular | 92 | 49.2 | 94 | 66.7 | 50 | 64.1 | 41 | 61.2 | 40 | 62.5 | 19 | 54.3 | 28 | 57.1 |

| Rheumatological | 57 | 30.5 | 39 | 27.7 | 20 | 25.6 | 38 | 56.7 | 28 | 43.8 | 17 | 48.6 | 20 | 40.8 |

| Endocrine | 44 | 23.5 | 50 | 35.5 | 34 | 43.6 | 30 | 44.8 | 24 | 37.5 | 13 | 37.1 | 19 | 38.8 |

| Neurological | 44 | 23.5 | 39 | 27.7 | 22 | 28.2 | 13 | 19.4 | 16 | 25.0 | 10 | 28.6 | 11 | 22.4 |

| Gastrointestinal | 25 | 13.4 | 8 | 5.7 | 16 | 20.5 | 11 | 16.4 | 14 | 21.9 | 2 | 5.7 | 6 | 12.2 |

| Urinary | 10 | 5.3 | 33 | 23.4 | 11 | 14.1 | 14 | 20.9 | 5 | 7.8 | 4 | 11.4 | 5 | 10.2 |

| Psychiatric | 22 | 11.8 | 19 | 13.5 | 11 | 14.1 | 6 | 9.0 | 12 | 18.8 | 4 | 11.4 | 7 | 14.3 |

| Renal | 6 | 3.2 | 31 | 22.0 | 8 | 10.3 | 12 | 17.9 | 2 | 3.1 | 3 | 8.6 | 4 | 8.2 |

| Respiratory | 10 | 5.3 | 19 | 13.5 | 5 | 6.4 | 2 | 3.0 | 9 | 14.1 | 2 | 5.7 | 2 | 4.1 |

| Cancer | 9 | 4.8 | 5 | 3.5 | 2 | 2.6 | 2 | 3.0 | 2 | 3.1 | 2 | 5.7 | 3 | 6.1 |

| Pharmacological management | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Corticosteroids | 152 | 81.3 | 120 | 85.1 | 70 | 89.7 | 51 | 76.1 | 37 | 57.8 | 25 | 71.4 | 39 | 79.6 |

| Prednisolone | 138 | 73.8 | 111 | 78.7 | 59 | 75.6 | 48 | 71.6 | 32 | 50.0 | 22 | 62.9 | 35 | 71.4 |

| Prednisone | 52 | 27.8 | 45 | 31.9 | 18 | 23.1 | 10 | 14.9 | 3 | 4.7 | 5 | 14.3 | 11 | 22.4 |

| Dexamethasone | 50 | 26.7 | 16 | 11.3 | 12 | 15.4 | 2 | 3.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 11 | 22.4 |

| Deflazacort | 13 | 7.0 | 4 | 2.8 | 13 | 16.7 | 1 | 1.5 | 4 | 6.3 | 4 | 11.4 | 4 | 8.2 |

| Betamethasone | 22 | 11.8 | 6 | 4.3 | 3 | 3.8 | 2 | 3.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 6.1 |

| Methylprednisolone | 6 | 3.2 | 5 | 3.5 | 1 | 1.3 | 1 | 1.5 | 3 | 4.7 | 1 | 2.9 | 2 | 4.1 |

| DMARDs | 112 | 59.9 | 114 | 80.9 | 58 | 74.4 | 57 | 85.1 | 44 | 68.8 | 33 | 94.3 | 31 | 63.3 |

| Azathioprine | 69 | 36.9 | 85 | 60.3 | 32 | 41.0 | 34 | 50.7 | 20 | 31.3 | 21 | 60.0 | 12 | 24.5 |

| Methotrexate | 22 | 11.8 | 34 | 24.1 | 33 | 42.3 | 18 | 26.9 | 22 | 34.4 | 6 | 17.1 | 14 | 28.6 |

| Chloroquine | 40 | 21.4 | 11 | 7.8 | 9 | 11.5 | 15 | 22.4 | 11 | 17.2 | 9 | 25.7 | 10 | 20.4 |

| Hydroxychloroquine | 13 | 7.0 | 3 | 2.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 3.0 | 3 | 4.7 | 1 | 2.9 | 3 | 6.1 |

| Sulfasalazine | 6 | 3.2 | 3 | 2.1 | 1 | 1.3 | 5 | 7.5 | 2 | 3.1 | 2 | 5.7 | 5 | 10.2 |

| Leflunomide | 5 | 2.7 | 0 | 0.0 | 5 | 6.4 | 5 | 7.5 | 1 | 1.6 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 2.0 |

| Colchicine | 43 | 23.0 | 2 | 1.4 | 2 | 2.6 | 7 | 10.4 | 30 | 46.9 | 1 | 2.9 | 7 | 14.3 |

| Other immunosuppressants | 10 | 5.3 | 14 | 9.9 | 3 | 3.8 | 6 | 9.0 | 6 | 9.4 | 1 | 2.9 | 3 | 6.1 |

| Mycophenolate | 5 | 2.7 | 7 | 5.0 | 2 | 2.6 | 2 | 3.0 | 1 | 1.6 | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 4.1 |

| Cyclosporine | 5 | 2.7 | 2 | 1.4 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 5 | 7.8 | 1 | 2.9 | 1 | 2.0 |

| Cyclophosphamide | 2 | 1.1 | 5 | 3.5 | 0 | 0.0 | 4 | 6.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 2.9 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Tacrolimus | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 1.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| DMARDb | 1 | 0.5 | 3 | 2.1 | 3 | 3.8 | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 3.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 2.0 |

| Tocilizumab | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 3.8 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 2.0 |

| Rituximab | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 2.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Adalimumab | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 3.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 2.0 |

| Etanercept | 1 | 0.5 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Comedications | 178 | 95.2 | 133 | 94.3 | 78 | 100.0 | 64 | 95.5 | 60 | 93.8 | 33 | 94.3 | 44 | 89.8 |

| Non-opioid analgesics | 141 | 75.4 | 91 | 64.5 | 58 | 74.4 | 46 | 68.7 | 47 | 73.4 | 25 | 71.4 | 39 | 79.6 |

| Antiulcer | 94 | 50.3 | 99 | 70.2 | 48 | 61.5 | 37 | 55.2 | 39 | 60.9 | 23 | 65.7 | 24 | 49.0 |

| Antihypertensives and diuretics | 70 | 37.4 | 85 | 60.3 | 49 | 62.8 | 33 | 49.3 | 35 | 54.7 | 15 | 42.9 | 19 | 38.8 |

| Lipid-lowering | 47 | 25.1 | 51 | 36.2 | 43 | 55.1 | 22 | 32.8 | 22 | 34.4 | 12 | 34.3 | 14 | 28.6 |

| Antihistamines | 88 | 47.1 | 38 | 27.0 | 15 | 19.2 | 22 | 32.8 | 17 | 26.6 | 7 | 20.0 | 17 | 34.7 |

| Platelet antiaggregants | 49 | 26.2 | 36 | 25.5 | 47 | 60.3 | 17 | 25.4 | 17 | 26.6 | 10 | 28.6 | 16 | 32.7 |

| Opioid analgesics | 58 | 31.0 | 36 | 25.5 | 17 | 21.8 | 17 | 25.4 | 18 | 28.1 | 9 | 25.7 | 22 | 44.9 |

| Antidepressants | 44 | 23.5 | 40 | 28.4 | 25 | 32.1 | 20 | 29.9 | 24 | 37.5 | 10 | 28.6 | 10 | 20.4 |

| Antiepileptics | 31 | 16.6 | 39 | 27.7 | 19 | 24.4 | 13 | 19.4 | 8 | 12.5 | 8 | 22.9 | 7 | 14.3 |

| Inhaled bronchodilators and corticosteroids | 24 | 12.8 | 37 | 26.2 | 13 | 16.7 | 11 | 16.4 | 9 | 14.1 | 8 | 22.9 | 7 | 14.3 |

IQR: Interquartile range; DMARDs: Synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs; DMARDb: Biological disease modifying antirheumatic drugs.

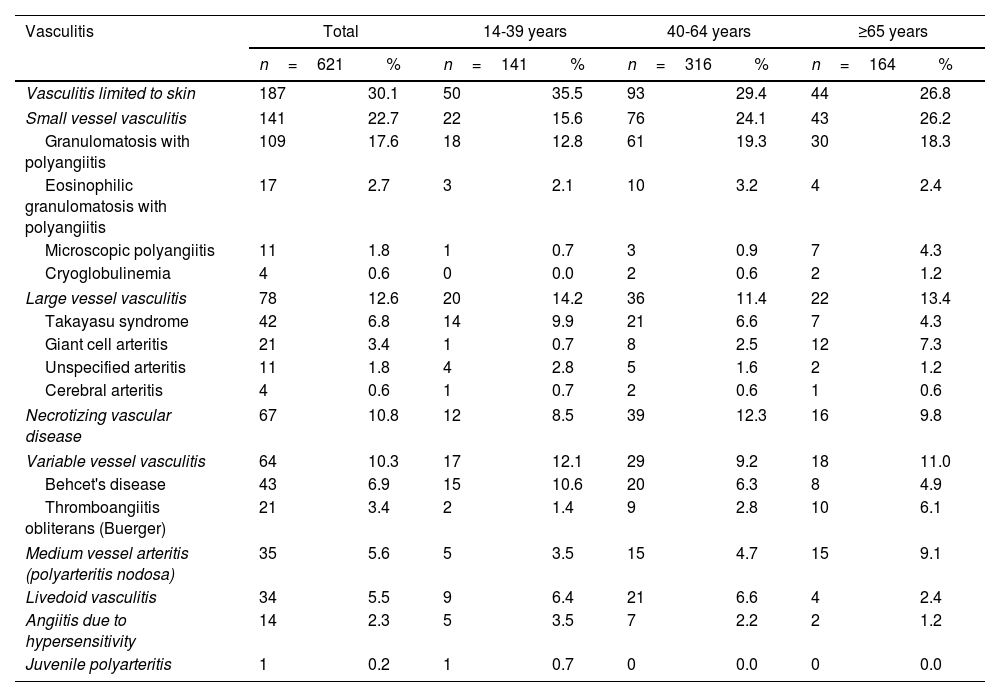

Vasculitis limited to the skin was the most common diagnosis (n=187; 30.1%), followed by granulomatosis with polyangiitis (n=109; 17.6%) and necrotizing vasculopathy (n=67; 10, 8%). Table 2 shows the distribution of systemic vasculitis according to age group. The pharmacological management of systemic vasculitis mainly involved the use of corticosteroids (n=503; 81.0%), especially prednisolone (n=445; 71.7%), followed by synthetic DMARDs (n=449; 72.3%), of which azathioprine (n=273; 44.0%), methotrexate (n=149; 24.0%) and chloroquine (n=105; 16.9%) predominated. Immunosuppressants (n=43; 6.9%), such as mycophenolate (n=19; 3.1%) and biological DMARDs (n=10; 1.6%), were not often prescribed (Table 1).

Characterization of patients diagnosed with systemic vasculitis with age groups, in a Colombian population, 2019-2020.

| Vasculitis | Total | 14-39 years | 40-64 years | ≥65 years | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n=621 | % | n=141 | % | n=316 | % | n=164 | % | |

| Vasculitis limited to skin | 187 | 30.1 | 50 | 35.5 | 93 | 29.4 | 44 | 26.8 |

| Small vessel vasculitis | 141 | 22.7 | 22 | 15.6 | 76 | 24.1 | 43 | 26.2 |

| Granulomatosis with polyangiitis | 109 | 17.6 | 18 | 12.8 | 61 | 19.3 | 30 | 18.3 |

| Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis | 17 | 2.7 | 3 | 2.1 | 10 | 3.2 | 4 | 2.4 |

| Microscopic polyangiitis | 11 | 1.8 | 1 | 0.7 | 3 | 0.9 | 7 | 4.3 |

| Cryoglobulinemia | 4 | 0.6 | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 0.6 | 2 | 1.2 |

| Large vessel vasculitis | 78 | 12.6 | 20 | 14.2 | 36 | 11.4 | 22 | 13.4 |

| Takayasu syndrome | 42 | 6.8 | 14 | 9.9 | 21 | 6.6 | 7 | 4.3 |

| Giant cell arteritis | 21 | 3.4 | 1 | 0.7 | 8 | 2.5 | 12 | 7.3 |

| Unspecified arteritis | 11 | 1.8 | 4 | 2.8 | 5 | 1.6 | 2 | 1.2 |

| Cerebral arteritis | 4 | 0.6 | 1 | 0.7 | 2 | 0.6 | 1 | 0.6 |

| Necrotizing vascular disease | 67 | 10.8 | 12 | 8.5 | 39 | 12.3 | 16 | 9.8 |

| Variable vessel vasculitis | 64 | 10.3 | 17 | 12.1 | 29 | 9.2 | 18 | 11.0 |

| Behcet's disease | 43 | 6.9 | 15 | 10.6 | 20 | 6.3 | 8 | 4.9 |

| Thromboangiitis obliterans (Buerger) | 21 | 3.4 | 2 | 1.4 | 9 | 2.8 | 10 | 6.1 |

| Medium vessel arteritis (polyarteritis nodosa) | 35 | 5.6 | 5 | 3.5 | 15 | 4.7 | 15 | 9.1 |

| Livedoid vasculitis | 34 | 5.5 | 9 | 6.4 | 21 | 6.6 | 4 | 2.4 |

| Angiitis due to hypersensitivity | 14 | 2.3 | 5 | 3.5 | 7 | 2.2 | 2 | 1.2 |

| Juvenile polyarteritis | 1 | 0.2 | 1 | 0.7 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

Comedications were found in 95.0% (n=590) of patients, and the 10 most prescribed pharmacological groups were nonopioid analgesics (n=447, 72.0%), antiulcer drugs (n=364; 58.6%), blood pressure drugs and diuretics (n=306; 49.3%), lipid-lowering drugs (n=211; 34.0%), antihistamines (n=204; 32.9%), antiplatelet drugs (n=192; 30.9%), opioid analgesics (n=177; 28.5%), antidepressants (n=173; 27.9%), antiepileptic drugs (n=125; 20.1%) and bronchodilators and inhaled corticosteroids (n=109; 17.6%) (Table 1).

Comparison of systemic vasculitis typesDifferent types of systemic vasculitis were predominant in women, and in older patients, there was a greater predominance of medium- and small-vessel vasculitis. Corticosteroids were less often prescribed for patients with variable vessel vasculitis; azathioprine was widely used for medium and small vessel vasculitis; and methotrexate use was predominant for large vessel vasculitis and variable vessel vasculitis. The greater use of colchicine and cyclosporine for variable vessel vasculitis was noteworthy (Table 1).

DiscussionIt was possible to identify a significant number of patients in Colombia with a diagnosis of systemic vasculitis in Colombia. The Chapel Hill classification, some sociodemographic variables and the pharmacological management of the disease were described. The average age of the patients with systemic vasculitis was 55 years, consistent with that reported in other studies.13–15 The disease predominantly affected women, as described in most reports.13,15,16 Although our series found a predominance of women, the data in the literature are variable and are related to the type of vasculitis, as in the studies by Vargas et al. in Chile and Flores-Suárez in Mexico, who reported a predominance of women with vasculitis associated with anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCAs),17,18 while Kitching et al. reported a 1:1 ratio of men and women.19

The most common type of vasculitis was limited to skin, in contrast with the findings of two previous studies conducted in Colombia.8,12 In one of them, Ochoa et al. reviewed the literature published in different databases on cases of vasculitis between 1945 and 2007 and unpublished literature sent directly by the authors, and they found that Takayasu arteritis was the most common type of vasculitis (13.3%), followed by Buerger's disease (11.2%), primary cutaneous vasculitis (10.0%) and polyarteritis nodosa (10.0%).8 In addition, Ramírez et al. documented that Takayasu arteritis was the most common vasculitis (21.8%), followed by polyarteritis nodosa (18.0%).12 The possible explanations for these variations may be the different methodologies used in these investigations, the types of vasculitis included, the diagnostic criteria used and the period of time for which patients were identified.

The epidemiology and distribution of vasculitis also varies according to country; for example, in Spain and Israel, there is a predominance of giant cell arteritis (39.1–55.1%)13,20; in Portugal, Iran and Egypt, Behcet's disease was predominant (42.5–76.0%)16,21,22; in the United Kingdom, granulomatosis with polyangiitis predominated (66.0%)23; and in Japan, microscopic polyangiitis was most common (83.0%).23 In Latin America, Iglesia et al. documented that Takayasu arteritis was the most common form of vasculitis in Brazil, Colombia and Mexico, whereas granulomatosis with polyangiitis predominated in Chile, and microscopic polyangiitis predominated in Peru.24 A study by Flores-Suarez in Mexico reported 102 patients with vasculitis associated with ANCAs between 1982 and 2010.18 These variations may be due to genetic factors (gene polymorphisms) and environmental variations, such as infections, seasons, ultraviolet radiation and chemical exposure.25–27 Regional differences in the incidence, prevalence and clinical characteristics of patients with systemic vasculitis should be considered at the time of diagnosis and the establishment of treatment.28

In this group of patients with systemic vasculitis, most were treated with corticosteroids (81.0%), although at a lower proportion than that found in Spain (100.0%).13 Similarly, azathioprine and methotrexate were the most frequently prescribed antirheumatics, which is consistent with what was found in Spain (31.8% and 10.9%, respectively)13 and in France (57.0% and 26.0%, respectively); in comparison, the rate of DMARDb prescriptions was very low (1.6%), in contrast with what was found in Portugal (8.6%).16 In this report, the use of colchicine predominated for variable vessel vasculitis; colchicine was also the predominant treatment in Portugal, but at a much lower rate (75.3%).16 In general, the pharmacological management provided for patients with systemic vasculitis was consistent with the recommendations of the clinical practice guidelines.11,29,30

Hypertension was the most common comorbidity in this report, which is consistent with reports for Spain (30.7%),13 Sweden (41.9–52.9%)15,31 and Germany (83.0%)32 and contributes to the increased cardiovascular risk of patients with systemic vasculitis.33 On the other hand, this report found that just over one-third of patients had an infection, which is consistent with other studies (27.1–32.3%).31,34 According to Mohammad, a cohort of patients with giant cell arteritis had a higher risk of severe infections than the general population (RR: 1.85; 95% CI: 1.57–2.18).31

There were some limitations in the interpretation of the results since access to medical records was not obtained to verify the patients’ diagnoses, paraclinical studies and hospitalizations or the activity, severity and complications of the disease; similarly, medications that were prescribed outside the health system or were not provided by the dispensing company were unknown, as was information about the patients’ pharmacological induction cycles. However, the study included a significant number of patients distributed throughout most of the national territory and included patients affiliated with both the contributory and subsidized regimes of the country's health system.

ConclusionsLastly, we can conclude that the pattern of prescriptions used to treat patients diagnosed with systemic vasculitis is heterogeneous and in accordance with current clinical management guidelines. Additionally, much of this population has associated comorbidities, which increases the use of medications. Despite the great advances in the diagnostic methods and management of vasculitis, there are still unresolved issues, such as recognizing and avoiding chronic limitations, improving adherence to treatment, ensuring clinical follow-up and knowing the needs of patients to improve their quality of life.

FundingThe present study did not receive funding.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflict of interest.

The authors acknowledge Soffy Claritza López for her work in obtaining the database.