Congenital pseudarthrosis of the clavicle is a rare malformation in which the aetiology is still unclear. Bilateral involvement is exceptional. Although it is a congenital malformation, it may not be diagnosed until late childhood, with patients presenting with a painless deformity of the middle third of the clavicle in the absence of prior trauma. The treatment is controversial, and may be surgical, depending on the functional impact and aesthetics. A case of bilateral involvement is presented, together with a review of the relevant literature.

La seudoartrosis congénita de clavícula es una rara malformación de etiología todavía no aclarada. La afectación bilateral es excepcional. Aun siendo una malformación congénita su diagnóstico puede prolongarse hasta avanzada la niñez, presentando los pacientes una deformidad indolora del tercio medio de la clavícula en ausencia de traumatismo previo. El tratamiento es controvertido, y puede ser quirúrgico o no según la repercusión funcional y estética. Presentamos un caso de afectación bilateral y analizamos la bibliografía encontrada al respecto.

We present the case of a male aged 3 months, the third of three siblings, whose delivery was normal with cephalic presentation. We detected a family history of “coffee stain” marks suggestive of neurofibromatosis inherited from the maternal grandmother and a sister.

In the study conducted by the neuropaediatric unit, no neurological changes were found in the patient.

The child was referred to the Department of orthopaedics and traumatology by his paediatrician after it was noted that he had a small lump in both clavicles.

Examination revealed normal movement of the neck and arms. There was an absence of asymmetry and there were small nodules in the middle third of both clavicles. The parents mentioned that at no time since birth had the child suffered from pain or impaired mobility.

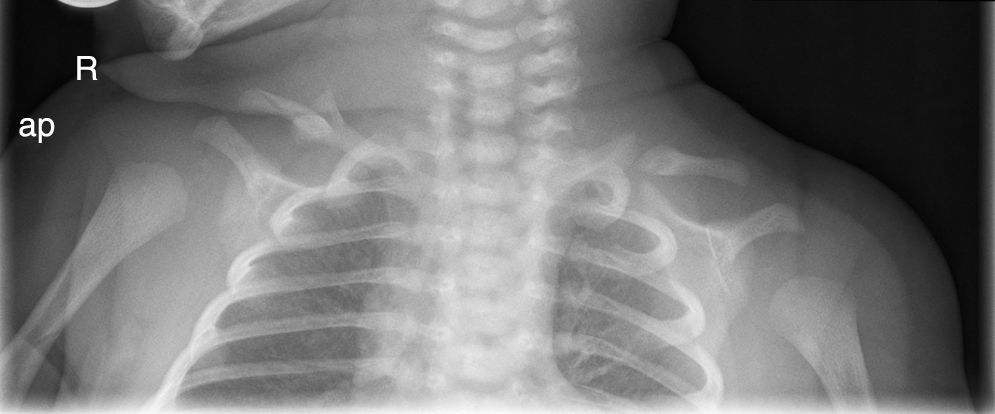

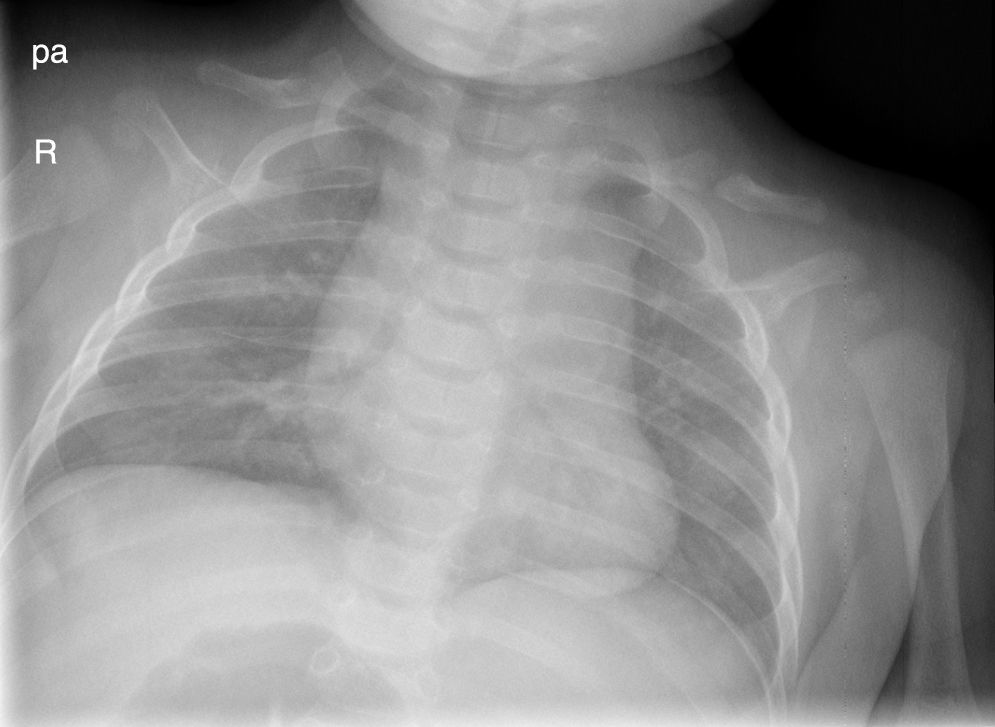

The X-ray at one week old (Fig. 1.) shows an image compatible with a fracture versus bilateral pseudarthrosis of the clavicles. The study was repeated at 4 months (Fig. 2) and the persistence of the image of pseudarthrosis may be observed in both clavicles. Since there was neither sign of consolidation nor any background of a traumatic birth or previous trauma, bilateral congenital pseudarthrosis of the clavicle was diagnosed.

Congenital pseudarthrosis of the clavicle is a rare pathology and there are few references to it in literature. 200 cases have been described in literature, most frequently in girls.1 Bilateralism is uncommon, and there are 7 published cases.2

Its aetiology has not been clarified with certainty. Several authors believe that this is due to a failure in the consolidation of the two ossification centres of the clavicle.3,4 Others believe it originates from a defect in embryological development during the initial stages.5 It has also been attributed to a causal link between the foetal head and cephalic delivery.5 Several authors have found a certain relationship between congenital pseudarthrosis of the clavicle and narrow superior thoracic outlet syndome,2 and between Ehlers–Danlos syndrome6 and neurofibromatosis.2

Although cases of autosomal inheritance have been described, in general their presentation is sporadic. However, autosomal dominant genetic transmission is a possibility. Cases of family involvement also exist. A relationship with the chromosome 10p11.21p127 has also been found.

Diagnosis is clinical and radiological. It presents as a painless deformity at the clavicle in the absence of any background of obstetric trauma and with no mobility impairment. It is usually diagnosed in the first few years of life, due to the aesthetic defect it entails. Usually the mother realises there is a lump.

In the majority of cases a biopsy is not necessary. An X-ray reveals the bone involvement at both ends of the clavicle with the middle and anterior bone fragment being wider than the lateral one.

If hypertrophic pseudarthrosis is present the anatomopathological imaging shows up hyaline cartilage1 with chondrocytes in different stages of maturity with the same pattern as that of the growth plate.4 If it is a case of atrophic pseudarthrosis we may have a pattern of fibrous connective tissue.1,5

Differential diagnosis must primarily take place with obstetric fracture of the clavicle. In these cases there may be a background of trauma, from, for example, a delivery with dystocia, macrosomia or the use of forceps. The fracture callus would be visible in an X-ray and there would be pain on physical examination. It is also necessary to differentiate from cleidocranial dysostosis,8 where the patient would also present with bulging fontanelles, an impairment in the development of the sternum, spine and pelvis in addition to having bilateral involvement and a family history of the condition.

With regards to treatment, this is controversial. Several authors prefer conservative treatment, provided that there are no functional limitations,1 vascular nerve compression and that the aesthetic defect is tolerated by the patient.3 Those who prefer surgical treatment advise non-intervention until the age of 4.1,2 The majority of authors only recommend surgery in the case of symptomatic patients or those with major deformities. Surgical correction basically consists of the resection of fibrous tissue and osteosynthesis using Kirschner9 needles or plates in addition to grafts.2,6

Prakash Chandran et al.10 in their study refer to a lower rate of infection and complications with the use of plates compared to osteosynthesis with Kirschner needles.

Unlike congenital pseudarthrosis, in post-traumatic pseudarthrosis the majority of patients require surgical treatment due to pain and impaired mobility associated with these lesions.

To conclude, we presented this case due to its exceptional nature, low prevalence and because it concerned a male patient with bilateral involvement.

We would highlight the scarcity of published literature in this regard and the absence of long term studies. As a result, from our point of view, it would be essential to carry out a follow-up of the patient to periodically assess the evolution of the condition. Should clinical symptoms, outstanding deformity and/or impairment of mobility occur we would suggest surgery be performed.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of people and animals subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments have been carried out on humans or animals for this investigation.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have adhered to the protocols of their centre of work regarding the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

FundingThere was no type of financing.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Please cite this article as: Nieto Gil A, Gómez Navalón A, Zorrilla Ribot P. Seudoartrosis congénita de clavícula bilateral. Caso clínico. Rev Esp Cir Ortop Traumatol. 2016;60:397–399.