Staphylococcus aureus stands as the predominant etiological agent in postoperative acute prosthetic joint infections (PJI), contributing to 35–50% of reported cases. This study aimed to evaluate the efficacy of dual prophylaxis incorporating cefuroxime and teicoplanin, in combination with nasal decolonization utilizing 70% alcohol, and oral and body lavage with chlorhexidine.

Material and methodsWe conducted a retrospective review of electronic health records regarding primary and revision arthroplasties conducted at our institution from 2020 to 2021. Relevant variables linked to prosthetic joint infections (PJI) were documented until the latest follow-up.

ResultsA total of 539 operations (447 primary arthroplasties and 92 revision arthroplasties) were performed on 519 patients. There were 11 cases of postoperative acute PJI, resulting in infection rates of 1.6% for primary arthroplasties and 4.3% for revision surgeries. Infections were more prevalent in male patients, individuals with an ASA classification>II, and those undergoing longer operations (>90min). S. aureus was not isolated in any of the cases.

ConclusionThe prophylactic measures implemented in our institution have exhibited a high efficacy in preventing postoperative acute PJI caused by S. aureus.

Staphylococcus aureus es el agente etiológico predominante en la infección aguda posoperatoria en cirugía protésica de la cadera, contribuyendo al 35-50% de los casos descritos. Este estudio tiene como objetivo evaluar la eficacia de la profilaxis dual que incorpora cefuroxima y teicoplanina, en combinación con la decolonización nasal utilizando alcohol al 70%, y el lavado oral y corporal con clorhexidina.

Material y métodosHemos realizado un estudio retrospectivo de los registros electrónicos de salud relacionados con artroplastia primaria y de revisión realizadas en nuestra institución desde 2020 hasta 2021. Se documentaron todas aquellas variables relevantes vinculadas a la infección protésica hasta el último seguimiento.

ResultadosSe llevaron a cabo un total de 539 operaciones (447 artroplastias primarias y 92 artroplastias de revisión) en 519 pacientes. Se registraron 11 casos de infección aguda posoperatoria, lo que resultó en tasas de infección del 1,6% para las artroplastias primarias y del 4,3% para las cirugías de revisión. Las infecciones fueron más prevalentes en pacientes varones, individuos con una clasificación ASA> II y aquellos sometidos a operaciones más prolongadas (> 90 minutos). No se aisló Staphylococcus aureus en ninguno de los casos.

ConclusiónLas medidas profilácticas implementadas en nuestra institución han demostrado una alta eficacia en la prevención de infección aguda posoperatoria causada por Staphylococcus aureus.

The utilization of preoperative antibiotics as a standard protocol in total joint arthroplasties has been linked to a substantial decrease in infection rates.1,2 Nevertheless, the prevailing incidence of prosthetic joint infections (PJI) is not exhibiting a decline, likely attributable to several factors such as an aging patient population with increased comorbidities, a heightened ratio of revision to primary operations, or an elevated resistance to cephalosporins among prevalent pathogens associated with orthopedic infections.3,4

Guidelines and international consensus among experts advocate for the administration of cefazolin or cefuroxime. In instances of cephalosporin allergy and/or for individuals harboring methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), the recommended alternatives include vancomycin or clindamycin.5–7 Recognizing the diminished efficacy of vancomycin as a sole prophylactic antibiotic, a combination approach involving cephalosporins and glycopeptides has been suggested, yielding favorable outcomes.8–10

The microorganism of greatest concern in PJI is Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus).4,11 A comprehensive previous study encompassing data from 345 cases of acute post-surgical PJI attributed to this pathogen, reported a failure rate of 45% for both methicillin-susceptible S. aureus (MSSA) and methicillin-resistant strains.12 Furthermore, various reports on PJI caused by diverse microorganisms have identified S. aureus as an independent predictor of failure.13,14

Nasal decolonization employing agents such as mupirocin, alcohol, iodine povidone, and chlorhexidine body lavage has been linked to a decrease in the incidence of surgical site infections caused by S. aureus.15,16 Nevertheless, the impact of combining dual prophylaxis and nasal decolonization remains unexplored.

In our institution, a combined approach involving dual prophylaxis with cefuroxime and teicoplanin, along with universal nasal decolonization using 70% alcohol, complemented by oral and body lavage with chlorhexidine was implemented in January 2020. The objective of this study was to assess the impact of this protocol on the prosthetic joint infection (PJI) rate attributable to S. aureus following both primary and revision total hip arthroplasty.

Material and methodsStudy designThis was a retrospective, descriptive, and non-experimental study including all consecutive elective primary hip arthroplasty and non-septic revision procedures were performed in our hospital between January 2020 and December 2021. The follow-up of the patients was 12 months.

Antibiotic prophylaxisIn the pre-operative phase, all patients, on the day of the surgical intervention, underwent nasal decolonization with 70% alcohol applied to both nostrils, a 1-min oral rinse with chlorhexidine, and body cleansing using towels saturated with chlorhexidine. Throughout the hospitalization period post-operation, nasal decolonization and oral rinsing were implemented twice daily, while body cleansing was performed once daily for 5 days or until discharge, whichever transpired first.

In the operating room, within the 60min preceding the beginning of the operation, patients received intravenous administration of cefuroxime (1.5g) and teicoplanin (800mg) in cases of primary arthroplasty and ceftazdime (2g) and teicoplanin (800mg) in cases of presumed aseptic revision arthroplasty. In instances where the surgical procedure extended beyond 2h, an additional dose of the cephalosporin was administered.

Definition of the outcomeAcute PJI was defined as presenting with clinical symptoms and signs of infection for ≤3 weeks, requiring open debridement and positive intraoperative cultures or in case of negative cultures, the presence of pus or high leukocyte count in synovial fluid of periprosthetic tissue according to the criteria included in the European Bone and Joint Infection Society (EBJIS) inclusion criteria.17

Ethical requirementsThe data used in the study was obtained from the medical records of the patients. Data was collected retrospectively and blindly analyzed. This study was reviewed and approved by the Ethical Institutional Review Board of the hospital with the code HCB/2023-0493.

Statistical analysisContinuous variables were described using mean and standard deviation (SD), and categorical variables were described using absolute numbers and percentages. Data was gathered in an Excel file, and analyses were performed using the IBM SPSS 29.0.0 Statistical Package (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL).

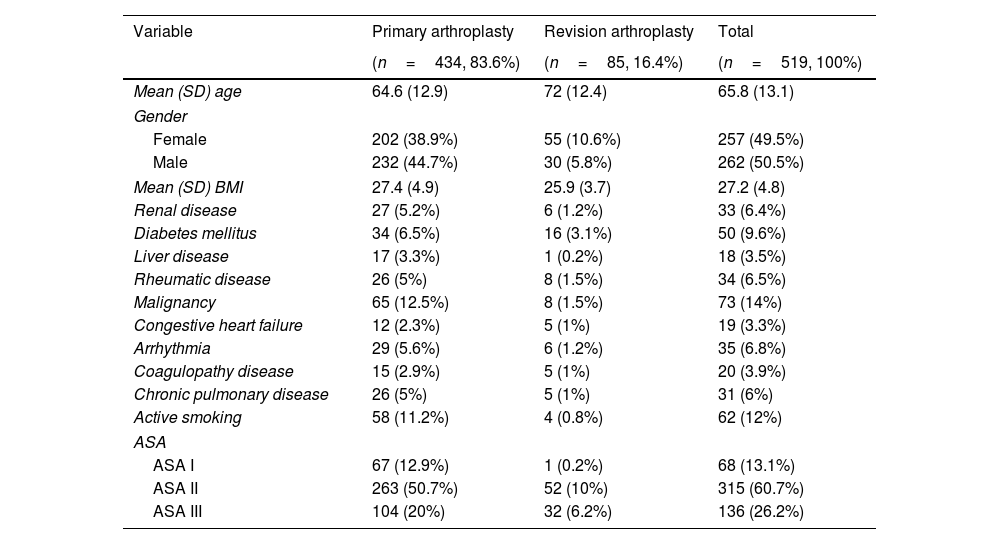

ResultsA total of 519 patients, comprising 262 men and 257 women, were included in the analysis. The mean follow-up period was 17.5 months (SD 6.4), with an average age of 65.8 years (SD 13.1) (Table 1). A total of 20 of the 519 patients received either bilateral hip arthroplasties or nonseptic revision surgeries of the primary prosthesis of the same hip. Thus, a total of 539 surgical interventions were finally analyzed, encompassing 447 primary arthroplasties and 92 revisions, with mean surgical durations of 107min (SD 32.5) and 145min (SD 52.1), respectively.

Main demographics of the patients included in the study according to the type of surgical procedure.

| Variable | Primary arthroplasty | Revision arthroplasty | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| (n=434, 83.6%) | (n=85, 16.4%) | (n=519, 100%) | |

| Mean (SD) age | 64.6 (12.9) | 72 (12.4) | 65.8 (13.1) |

| Gender | |||

| Female | 202 (38.9%) | 55 (10.6%) | 257 (49.5%) |

| Male | 232 (44.7%) | 30 (5.8%) | 262 (50.5%) |

| Mean (SD) BMI | 27.4 (4.9) | 25.9 (3.7) | 27.2 (4.8) |

| Renal disease | 27 (5.2%) | 6 (1.2%) | 33 (6.4%) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 34 (6.5%) | 16 (3.1%) | 50 (9.6%) |

| Liver disease | 17 (3.3%) | 1 (0.2%) | 18 (3.5%) |

| Rheumatic disease | 26 (5%) | 8 (1.5%) | 34 (6.5%) |

| Malignancy | 65 (12.5%) | 8 (1.5%) | 73 (14%) |

| Congestive heart failure | 12 (2.3%) | 5 (1%) | 19 (3.3%) |

| Arrhythmia | 29 (5.6%) | 6 (1.2%) | 35 (6.8%) |

| Coagulopathy disease | 15 (2.9%) | 5 (1%) | 20 (3.9%) |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 26 (5%) | 5 (1%) | 31 (6%) |

| Active smoking | 58 (11.2%) | 4 (0.8%) | 62 (12%) |

| ASA | |||

| ASA I | 67 (12.9%) | 1 (0.2%) | 68 (13.1%) |

| ASA II | 263 (50.7%) | 52 (10%) | 315 (60.7%) |

| ASA III | 104 (20%) | 32 (6.2%) | 136 (26.2%) |

SD: standard deviation, BMI: body mass index, ASA: American Society of Anesthesiologist physical status classification system.

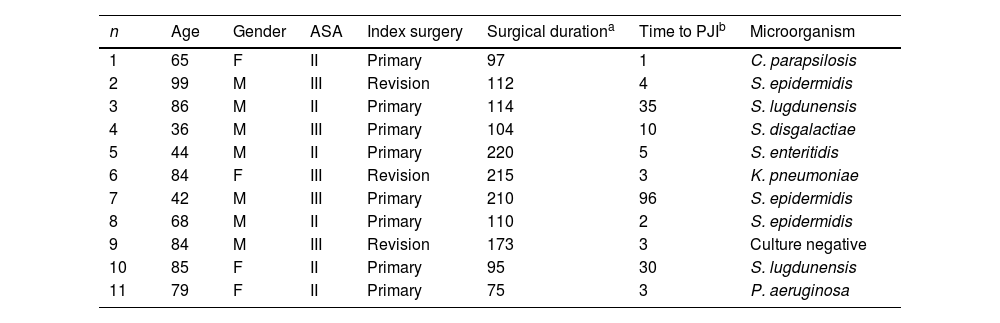

Throughout the follow-up period, out of the 539 surgical interventions, 11 (2%) resulted in prosthetic joint infection: 7 cases occurred following primary arthroplasties (1.6%), and 4 cases after revision operations (4.3%). Among the cases with a surgical duration of less than 90min (103 cases), only 1 case developed PJI (0.9%). In the group with a duration of 90–120min (218 cases), 6 patients presented with an infection (2.8%). In the remaining 218 cases where the intervention exceeded 120min, 4 patients developed an infection (1.8%).

Upon analyzing the characteristics of the 11 PJI, 7 cases involved male patients; 6 had an ASA classification of II, and 5 had an ASA classification of ≥III. Up to 8 cases were classified as early acute infections, occurring within the first 4 postoperative weeks, and 2 occurred between 5 and 12 weeks postoperatively. The remaining 3 patients experienced late acute PJI, occurring after than 3 months from the index surgery.

The isolated pathogens in the PJI included Staphylococcus epidermidis in 3 cases, Staphylococcus lugdunensis in 2 cases, extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae in 1 case, Streptocuccus disgalactiae in 1 case, Salmonella enteritidis in 1 case, Pseudomonas aeruginosa in 1 case and Candida parapsilopsis in 1 case. There was a single case in which preoperative cultures from wound exudate were positive for P. aeruginosa, but intraoperative cultures were negative (Table 2).

Main characteristics of the patients who developed prosthetic joint infection (PJI).

| n | Age | Gender | ASA | Index surgery | Surgical durationa | Time to PJIb | Microorganism |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 65 | F | II | Primary | 97 | 1 | C. parapsilosis |

| 2 | 99 | M | III | Revision | 112 | 4 | S. epidermidis |

| 3 | 86 | M | II | Primary | 114 | 35 | S. lugdunensis |

| 4 | 36 | M | III | Primary | 104 | 10 | S. disgalactiae |

| 5 | 44 | M | II | Primary | 220 | 5 | S. enteritidis |

| 6 | 84 | F | III | Revision | 215 | 3 | K. pneumoniae |

| 7 | 42 | M | III | Primary | 210 | 96 | S. epidermidis |

| 8 | 68 | M | II | Primary | 110 | 2 | S. epidermidis |

| 9 | 84 | M | III | Revision | 173 | 3 | Culture negative |

| 10 | 85 | F | II | Primary | 95 | 30 | S. lugdunensis |

| 11 | 79 | F | II | Primary | 75 | 3 | P. aeruginosa |

F: female, M: male, ASA: American Society of Anesthesiologist physical status classification system, PJI: prosthetic joint infection.

While the incidence of prosthetic infections in primary operations is estimated to be up to 2%, the incidence in revision procedures ranges from 3 to 10%.18 Our results align with these rates, demonstrating an incidence of 1.6% in primary and 4.3% in revision arthroplasties. S. aureus stands out as a primary causative agent of PJI according to the literature. Triantafyllopoulos et al.19 retrospectively analyzed 36.494 patients undergoing total hip arthroplasty, identifying 154 PJI, with S. aureus isolated in 42.2% of cases, comprising 29.2% methicillin-susceptible S. aureus (MSSA) and 13% methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA). In addition, S. aureus has been identified as a crucial predictor of treatment failure following the debridement, antibiotic treatment, and implant retention (DAIR) approach.13 A multinational cohort study by Espindola et al.20 reported a failure rate of 32.8% in infections caused by S. aureus. Consequently, strategies aimed at reducing the frequency of S. aureus infections are of paramount importance. In a previous study, we demonstrated that the addition of teicoplanin to cefuroxime in joint arthroplasty significantly reduced, though not eradicated, S. aureus infections.8 Recently, authors from the United Kingdom showed that prophylactic regimens containing teicoplanin were as effective as other regimens, including cephalosporins, but S. aureus continued to be an etiologic agent in infected cases.21

The need for dual antibiotic prophylaxis is based on our previously published experience.8 We are aware that this is not the usual strategy. However, a recent study by Azamgarhi et al. regarding another center in the United Kingdom reported positive experiences with the combination of teicoplanin and gentamicin for antimicrobial prophylaxis in primary total joint arthroplasty.22 The goal in both cases is to cover the maximum number of potentially causative microorganisms for prosthetic infection. This necessitates incorporating coverage against methicillin-resistant coagulase-negative staphylococci, which are resistant to the cephalosporins typically used for prophylaxis (cefazolin and cefuroxime). Teicoplanin is a convenient and well-tolerated option for achieving this. We prefer to maintain cefuroxime rather than switching to gentamicin, as we encounter fewer issues with gram-negative bacilli resistant to cephalosporins. Additionally, we avoid nephrotoxicity, which was observed in the study by Azamgarhi et al.22 These data are the result of retrospective observational studies and may be associated with multiple biases, so controlled studies in the future will be necessary to address these questions.

Pre-operative S. aureus decolonization, employing nasal mupirocin or 60–90% alcohol, has effectively proved to reduce surgical site infections caused by S. aureus.15,23,24 In addition, the combination of nasal decolonization with body application of chlorhexidine has demonstrated a synergistic effect, significantly reducing infection rates.25,26 In this study, we assessed the impact of dual prophylaxis with teicoplanin and cefuroxime, in conjunction with nasal decolonization using 70% alcohol and body wash with chlorhexidine. The key finding is that, after more than 500 operations spanning two years, no infection due to S. aureus was detected. During the study follow-up, a total of 11 cases of PJI were diagnosed, yet none were attributed to S. aureus, demonstrating a 100% efficacy in the utilized prophylactic program.

The present study features some inherent limitations mainly related to its retrospective nature. The second limitation is the limited number of cases, as a consequence of being a single center study, however the patient population from a large teaching hospital reflects a realistic representation of daily practice without exclusion of patients with relevant comorbidities.

ConclusionsIn conclusion, antibiotic prophylaxis with cefuroxime and teicoplanin, combined with nasal decolonization using 70% alcohol and oral and body washing with chlorhexidine, as part of routine practice in antibiotic prophylaxis for hip arthroplasty operations proves to be an effective approach in reducing prosthetic joint infections caused by S. aureus.

Level of evidenceLevel of evidence iii.

Ethical considerationsThe authors confirm that the current study was reviewed by an Ethics Committee for Clinical Investigation, approved under the code HCB/2023-0493 and was conducted in accordance with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration.

FundingThis research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

DeclarationsThe authors did not receive support from any organization for the submitted work. All authors certify that they have no affiliations with or involvement in any organization or entity with any financial interest or non-financial interest in the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript.

Conflict of interestAt the time of publication none of the authors have any potential conflicts of interest to disclose. All authors declare that they have no affiliations that might affect the presentation of this research.

None.