Occipito-cervical metastases correspond to 0.5% of spinal metastases. The management of these lesions is complex and involves multiple radiological studies, such as simple radiology, computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Is vascular involvement is suspected, tests to assess vascular permeability are also recommended (angioCT). This type of lesion, due to its complex location, may require different types of approaches, commonly it will be the posterior approach, but sometimes anterior or antero-lateral approaches will be needed assisted by maxillofacial surgeons or otorhinolaryngologists for correct excision of the tumour. Pain with head turning can guide us to the diagnosis in an unstable spine. Magnetic resonance is the test of choice to diagnose and study these lesions. The presence of instability or progressive neurological symptoms is an indication for surgery.

Las metástasis a nivel occipitocervical corresponden solo al 0,5% de las metástasis del raquis. El manejo de estas lesiones es complejo y conlleva múltiples estudios radiológicos, tales como la radiología simple, la tomografía computarizada (TC) o la resonancia magnética (RM). Ante la sospecha de afectación vascular también será recomendable la realización de pruebas que valoren la permeabilidad vascular (angio-TC, angio-RM). Este tipo de lesiones, debido a su compleja localización, puede precisar distintos tipos de vías de abordaje; comúnmente será el abordaje posterior, pero en ocasiones se necesitarán abordajes anteriores o anterolaterales asistidos por cirujanos maxilofaciales u otorrinolaringólogos para una correcta exéresis de la tumoración. El dolor con los giros puede orientarnos al diagnóstico en una columna inestable. La RM es la prueba de elección para diagnosticar y estudiar estas lesiones. La presencia de inestabilidad o de clínica neurológica progresiva es indicación de cirugía.

The spine is the most frequent location of bone metastases, which affect the cervical spine in up to 15%, but only .5% at occipito-cervical level. Tumours of the occipito-cervical junction are defined according to the involvement of the condyles and/or the atlanto-axial column.1,2 The median survival of patients with spinal metastases is 10 months, and as a result, the goal will generally be local control of the disease; reduction of pain; improvement of neurological function, and maintenance of stability. The treatment of metastases at the occipito-cervical level represents a significant therapeutic challenge, given the peculiar anatomy of the area and the neurovascular structures that may be affected.3

In order to carry out a correct treatment of these patients, the following must be taken into account: the intraspinal extension, which will determine the possibility of oncological resection; the neurological and general status of the patient, as well as the histology of the initial tumour, differentiating between aggressive tumours that are difficult to control oncologically, such as pancreatic or gastric cancer, from tumours with better long-term control and less aggressiveness, such as breast cancer. The appearance of spinal cord compression conditions the patient's quality of life, so that, regardless of the prognostic assessment scales used, surgery may be indicated. It is not uncommon for a patient to present with a neurological lesion with a metastasis and a tumour of unknown origin, which further complicates decision-making.4

The origin of the metastasis is of paramount importance. In fact, tumours such as lymphoma, myeloma or plasmacytoma will respond very well to treatment by radiotherapy, which will reduce tumour size, improve neurological damage, if applicable, and allow surgery, if indicated, in cases of instability of the affected region. The vascularisation of the tumour must also be taken into account, since renal, thyroid, or hepatocellular carcinomas are highly vascularised and the possibility of embolisation of these should be considered beforehand.

Clinical diagnosisThe clinical presentation of tumours located in the cervico-occipital hinge is usually very discreet, progressing very slowly. This leads to delayed diagnosis which tends to be given when these tumours are larger. The most common clinical presentation is cervical pain and occipital neuralgia, as well as suboccipital and retroauricular headaches. Pain with rotation is present in up to 90% of cases when occipito-cervical involvement is present.5 The presence of myelopathy, however, is rare, being present in 0–22% of cases, due to the fact that the spinal canal is highly spacious in this region.

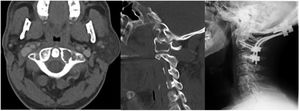

Diagnosis by imagingThe first test to be performed is a plain X-ray to check for correct alignment of the cervical spine. In half of the cases no pathological findings will be found, and in others it may show lytic or sclerotic areas, as well as alterations in alignment.

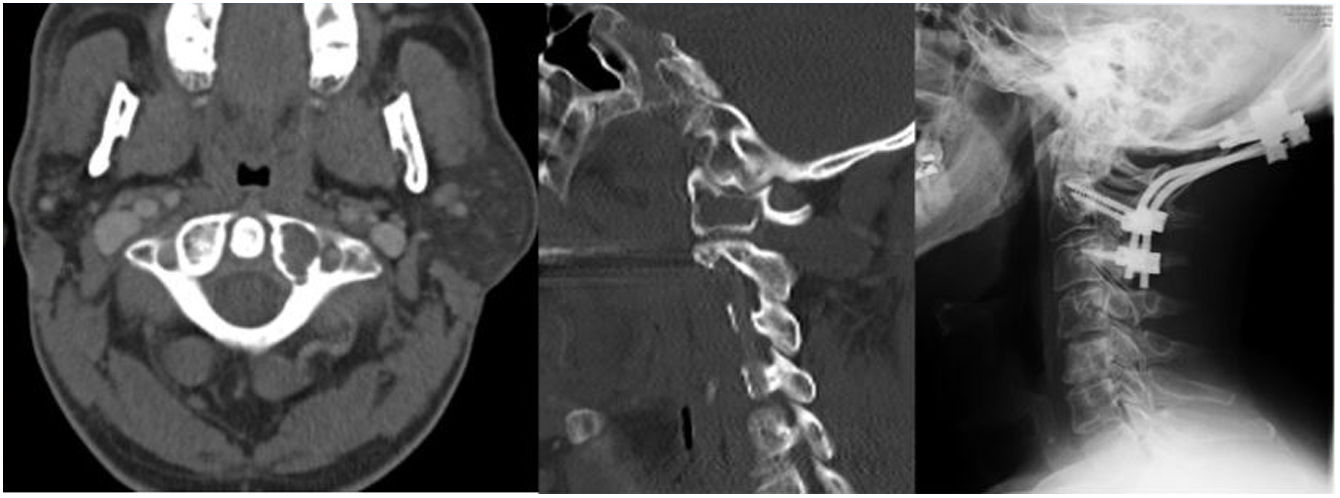

The CT scan and its reconstructions will serve to define the lytic lesion; the coronal, sagittal and axial planes will be assessed to analyse the degree of bone destruction, as well as the involvement of elements that may alter the stability of the cervico-occipital hinge (condyles). CT is also essential for correct preoperative planning, to plan the resection areas and their relationship with the structures to be preserved.

If vascular involvement is suspected, or in cases where the tumour is close to vascular structures, CT angiography or MRI angiography is recommended, where the relationship with the vertebral and carotid arteries will be verified, facilitating safer surgery.

The diagnostic test par excellence in this type of tumour is magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and by means of the different sequences, a probable diagnosis of its nature can be made, as well as a greater analysis of the state of the surrounding soft tissues, such as the ligaments. A complete extension study is also necessary, since factors such as the presence of visceral metastases and bone metastases in other locations influence the decision-making process for the management of these patients.

Management: radiation versus surgerySpinal metastases management varies constantly due to advances in the different types of adjuvant treatment, and better general control of the disease. In general, surgery is indicated in patients with over 6–12 months life expectancy (its indication in survival below 3 months is more controversial),6 in addition to spines with instability or with progressive neurological symptoms.

Bilsky et al.5 recommend non-surgical treatment in patients with correct alignment and/or minimal subluxation, regardless of histology and tumour radio-sensitivity. Surgery would be indicated in cases with instability criteria, including: atlanto-axial displacement>5mm, unilateral condylar destruction of 70%, bilateral condylar destruction>50%, angulation>11° with displacement of >3.5mm, or with persistent pain despite radiotherapy.

In cases where conservative treatment is the treatment of choice, we must bear in mind that radiotherapy has better results in prostate and breast metastases, and worse in renal and pulmonary metastases, and that similar results are obtained with a single dose (8Gy) and with fractionated doses of radiation, considering in certain cases the possibility of stereotactic radiosurgery.

Adjuvant hormonal chemotherapy will play a role in hormone-sensitive tumours (breast, thyroid and small cell lung carcinomas).

Multidisciplinary management between oncologists, pathologists, radiologists, radiotherapists, anaesthesiologists and surgeons is essential to reach the best decision for each patient.

Evaluation and instability scalesThere are a multitude of prognostic rating scales, most notably the Baue's, Tokuhashi's and Tomita's scales.

The modified Bauer scale7,8 gives 1 point for each of the following prognostic factors: (1) absence of internal organ metastases; (2) solitary skeletal metastasis; (3) absence of lung cancer; and (4) primary breast, kidney, lymphoma or multiple myeloma. The total points are classified into three prognostic groups, with median overall survival of 4.8 (score between 0 and 1), 18.2 (score of 2) and 28.4 (score of 3 and 4) months each.6

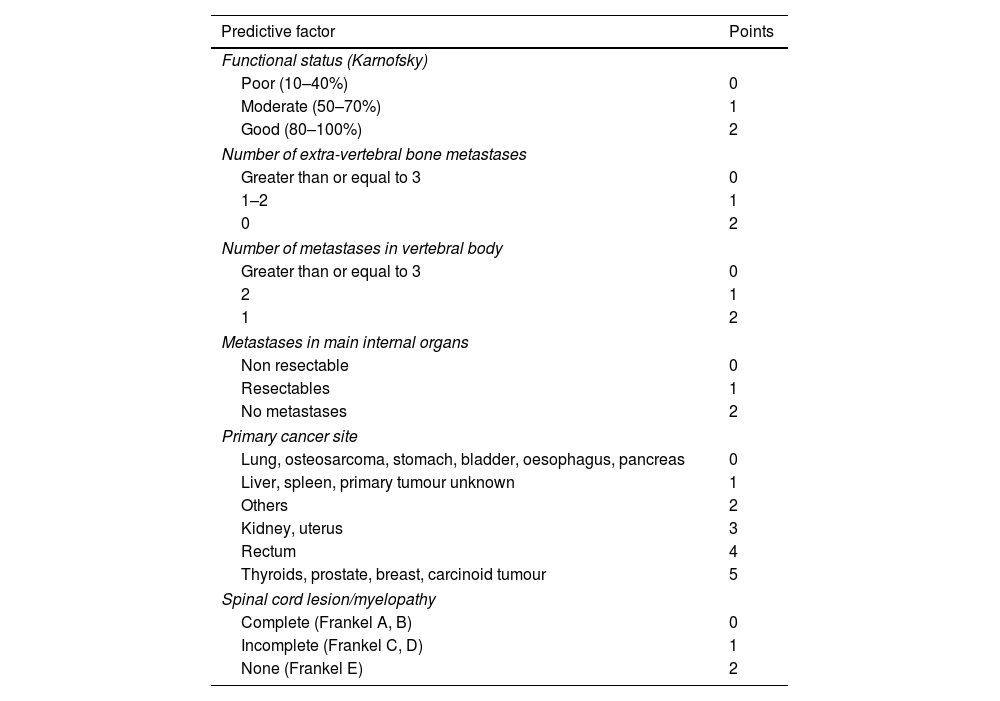

The Tokuhashi classification system9 takes into account the patient's general condition, the original tumour, the presence of visceral and bone metastases and neurological involvement and a fairly reliable assessment has been established for most tumours (Table 1).

Modified Tokuhashi prognostic scale.

| Predictive factor | Points |

|---|---|

| Functional status (Karnofsky) | |

| Poor (10–40%) | 0 |

| Moderate (50–70%) | 1 |

| Good (80–100%) | 2 |

| Number of extra-vertebral bone metastases | |

| Greater than or equal to 3 | 0 |

| 1–2 | 1 |

| 0 | 2 |

| Number of metastases in vertebral body | |

| Greater than or equal to 3 | 0 |

| 2 | 1 |

| 1 | 2 |

| Metastases in main internal organs | |

| Non resectable | 0 |

| Resectables | 1 |

| No metastases | 2 |

| Primary cancer site | |

| Lung, osteosarcoma, stomach, bladder, oesophagus, pancreas | 0 |

| Liver, spleen, primary tumour unknown | 1 |

| Others | 2 |

| Kidney, uterus | 3 |

| Rectum | 4 |

| Thyroids, prostate, breast, carcinoid tumour | 5 |

| Spinal cord lesion/myelopathy | |

| Complete (Frankel A, B) | 0 |

| Incomplete (Frankel C, D) | 1 |

| None (Frankel E) | 2 |

Score total (ST): 0–8 points≤6 months survival; 9–11 points≥6 months survival; 12–15 points≥1 year survival.

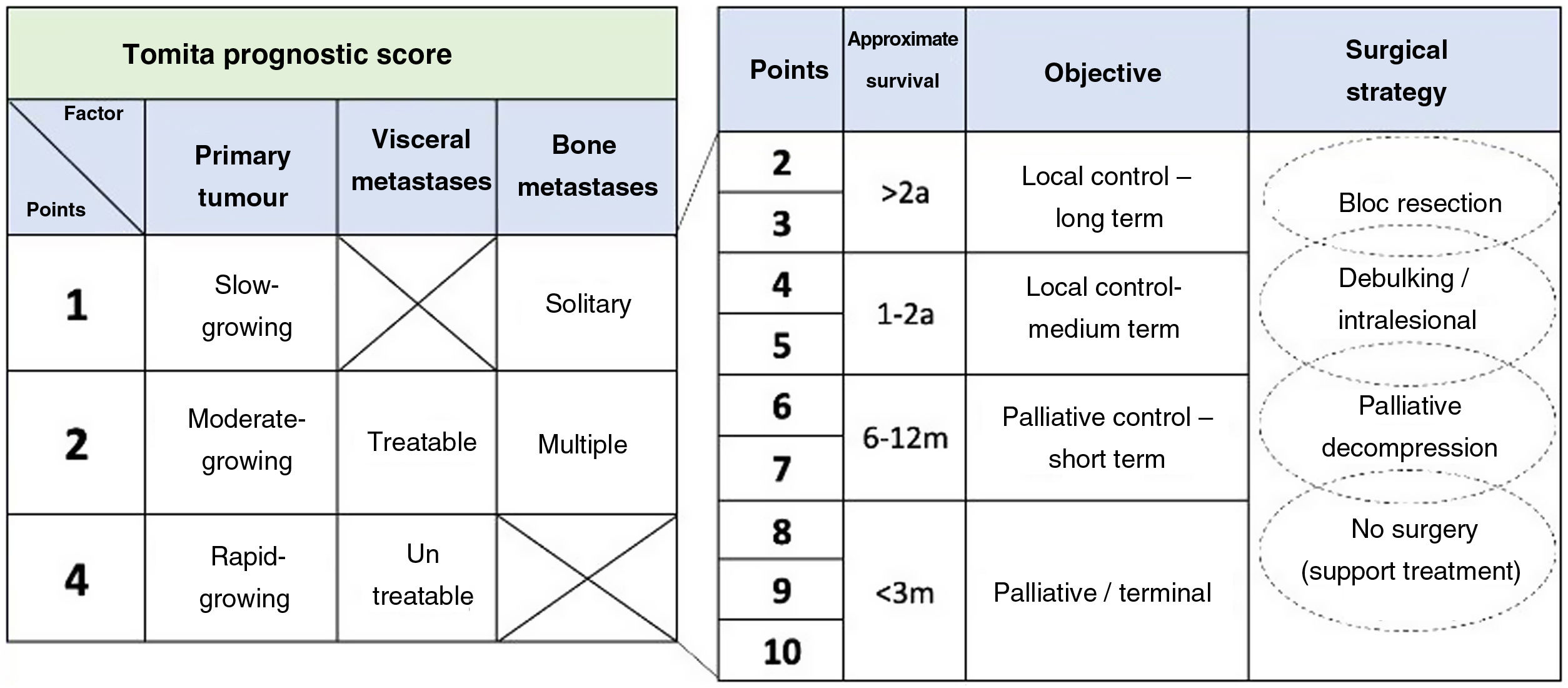

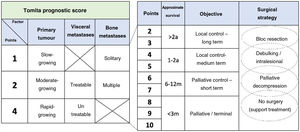

The Tomita system10 assesses the original tumour, differentiating between slow, moderate or rapid-growing tumours, the number of visceral and bone metastases, proposing a treatment plan according to the calculated survival for each case (Fig. 1).

Against this backdrop we can reach a decision and an assessment of the prognosis of our patients, but there are other key issues, such as neurological compression, vertebral instability and general patient status.

It is widely established that, in the face of neurological compression, surgical treatment is indicated in most cases, mainly to improve the patient's quality of life.11 In this regard, the NOMS algorithm by Bilsky and Smith12 helps to assess spinal cord compression, and analyses neurological status (N), oncological status (O), mechanical instability (M) and systemic disease (S).

The general status of the patient should be considered, as suggested by the treatment algorithm proposed by the Boriani group.13

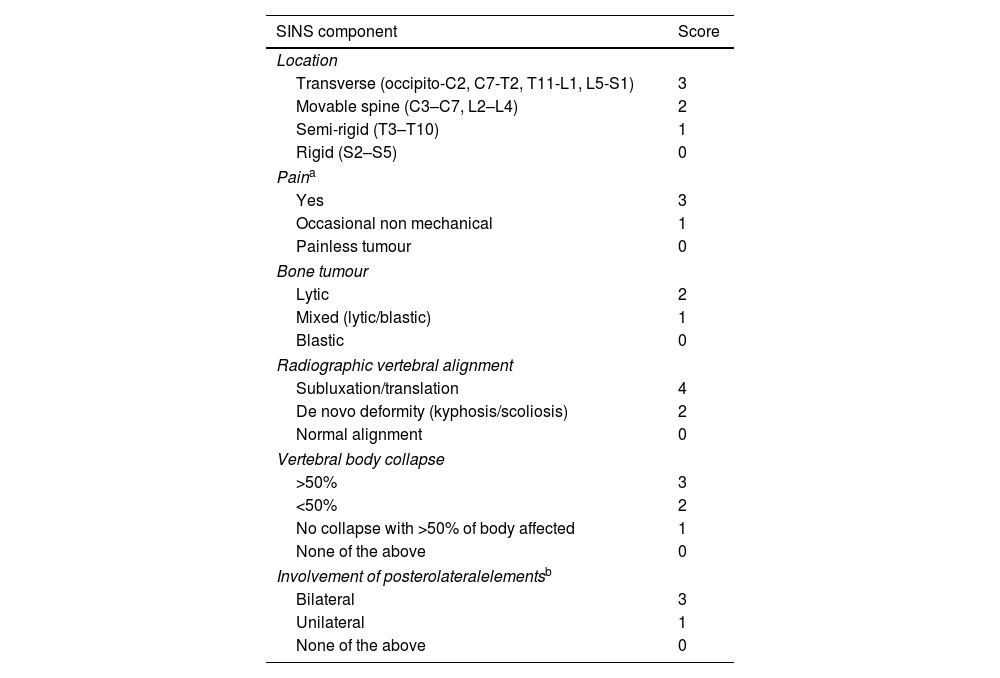

The scale most currently used to assess spinal stability is the Spine Instability Neoplastic Score (SINS), developed by the Spine Oncology Study Group14,15 and globally accepted,16 with 96% sensitivity and 80% specificity. It assesses 6 aspects: location; presence of pain; radiological alignment; involvement of posterior elements; degrees of vertebral body collapse and tumour morphology (Table 2).

SINS: Spinal Instability Neoplastic Score classification.

| SINS component | Score |

|---|---|

| Location | |

| Transverse (occipito-C2, C7-T2, T11-L1, L5-S1) | 3 |

| Movable spine (C3–C7, L2–L4) | 2 |

| Semi-rigid (T3–T10) | 1 |

| Rigid (S2–S5) | 0 |

| Paina | |

| Yes | 3 |

| Occasional non mechanical | 1 |

| Painless tumour | 0 |

| Bone tumour | |

| Lytic | 2 |

| Mixed (lytic/blastic) | 1 |

| Blastic | 0 |

| Radiographic vertebral alignment | |

| Subluxation/translation | 4 |

| De novo deformity (kyphosis/scoliosis) | 2 |

| Normal alignment | 0 |

| Vertebral body collapse | |

| >50% | 3 |

| <50% | 2 |

| No collapse with >50% of body affected | 1 |

| None of the above | 0 |

| Involvement of posterolateralelementsb | |

| Bilateral | 3 |

| Unilateral | 1 |

| None of the above | 0 |

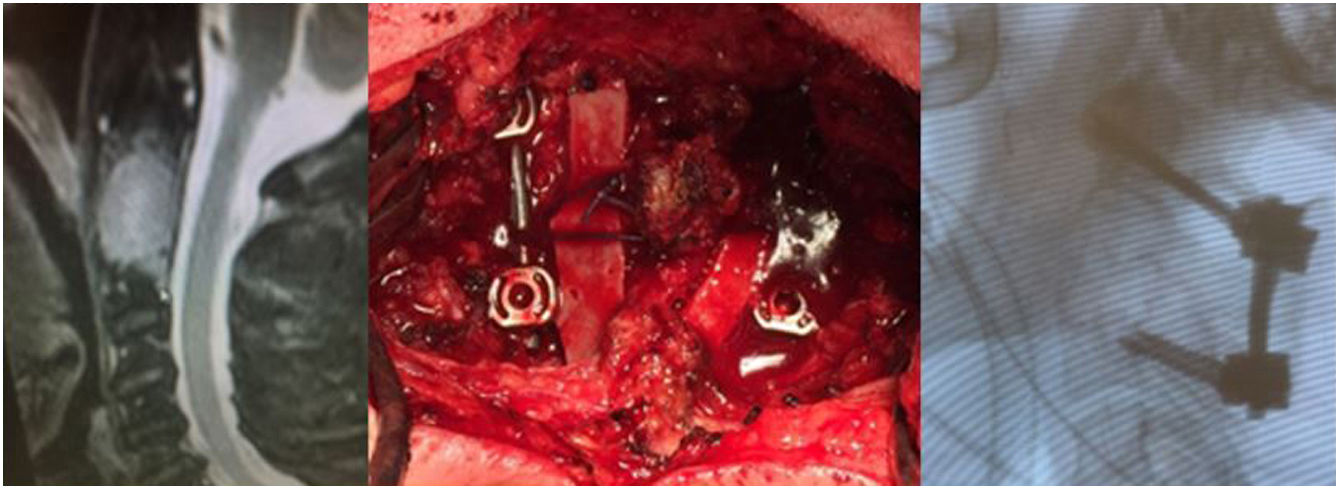

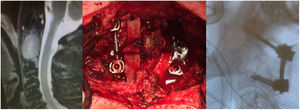

Tokuhashi classification scale is useful for surgical indication decision. Criteria for instability and indication for surgical stabilisation are established when there is a subluxation fracture>5mm, unilateral condylar destruction of 70% or bilateral condylar destruction>50% (Figs. 2 and 3).17,18

Once the surgical indication has been made,19,20 the approach to be used must be chosen. The most common approach is a posterior approach, which allows access to the posterior elements of the occipito-cervical junction. The variability of the vertebral artery21 must be taken into account, and therefore a CT angiography or MRI angiography should be performed prior to any intervention.

In addition to the posterior approach, there is the transoral approach,22,23 indicated for irreducible anterior compression, which allows access from the clivus to the body of C3 and the possibility of fixation with a plate. The posterolateral approach,24 also exists and this allows access to the anterior and lateral areas of the occipito-cervical junction. It is particularly suitable when there is a highly vascularised lesion, but if fixation is required, bilateral exposure will be necessary. These anterior or antero-lateral approaches sometimes require the assistance of maxillofacial surgeons or otorhinolaryngologists, as a thin layer of pharyngeal tissue may remain over the operated area, requiring local rotational flaps or vascularised free flaps to cover it. It is important to note that postoperatively, after a transoral/transmandibular approach, delayed orotracheal extubation, feeding tubes and monitoring of diet and swallowing may be required.

Regarding which instrumentation to use, screws25 are recommended over wires, as they achieve better pain relief, correction of alignment and a higher fusion rate.26 Kato et al.27 concluded that the use of Luque sublaminar instrumentation in upper cervical spine metastases provided significant stability for pain relief, even in late-stage disease, as long as the patient's general condition allows such surgical intervention.

ConclusionsWe can conclude that metastases of the occipito-cervical junction are rare lesions that initially produce few clinical symptoms. As these lesions increase in size, they may cause pain and/or instability.

Surgical treatment will be considered in those patients with a life expectancy of 6–12 months or more. In those with a survival of 3 months or less, the indication is controversial.

The main indication for surgery is when there is persistent pain, neurological deficit or instability criteria: atlanto-axial displacement>5mm; unilateral condylar destruction of 70%; bilateral condylar destruction>50%; angulation>11° with displacement of >3.5mm, requiring in these cases a complete radiological study due to the characteristic anatomy and proximity to important vascular structures (vertebral and carotid arteries).

Level of evidenceLevel of evidence iv.

FundingThis study did not receive any grants or funding.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.