To analyze the waiting periods elapsed since soft tissue sarcomas become symptomatic until their specific treatment in our unit, and to determine new strategies for the improvement of referral circuits.

Material and methodsThis is an ambispective observational study of a cohort of 61 patients, with previously untreated soft tissue sarcomas, obtained from our musculoskeletal tumors database. Several variables related to the patient, tumor, and health care circuit were analyzed, as well as the different periods between the initial symptoms of the disease and the first consultation in our unit. The significance level was α=0.05.

ResultsThe mean size of the sarcomas was 11.3cm. Thirty-six patients (59%) followed the usual circuit of the National Health System in Spain. The time elapsed since the disease became symptomatic until the first medical consultation was greater than 9.5 months, and nearly another 8.5 months to the consultation in our specific unit. Statistically significant relationships were found between the independent and dependent variables.

DiscussionThe study shows that the care of patients with soft tissue sarcomas in our environment is far away from the times of care in our neighboring countries.

ConclusionsIt is essential to make the population and health professionals aware of this disease, as well as to remember that there is a referral circuit that must be used.

Analizar los tiempos de espera transcurridos desde que los sarcomas de partes blandas (SPB) se hacen sintomáticos hasta su tratamiento específico en nuestra Unidad de Tumores Músculo-Esqueléticos (UTME) para proponer estrategias de mejora en los circuitos de derivación.

Material y métodosEstudio observacional, longitudinal y ambispectivo de una cohorte de 61 pacientes con SPB vírgenes obtenidos e identificados de forma continua del registro de pacientes de la UTME. Se analizó la relación entre diferentes tiempos transcurridos desde que la enfermedad se hizo sintomática hasta la primera consulta en la UTME, y diversas variables ligadas a la persona, tumor y circuito asistencial. Se usó un nivel de significación α=0,05.

ResultadosEl tamaño medio de los sarcomas fue de 11,3cm. Treinta y seis pacientes (59%) siguieron el circuito habitual del Sistema Nacional de Salud en nuestro país. El tiempo medio transcurrido desde que la enfermedad se hizo sintomática hasta la primera consulta médica fue superior a 9,5 meses; y el que transcurrió desde esta hasta la primera en nuestra UTME fue de casi 8,5 meses. Algunas variables independientes mostraron relación estadísticamente significativa con las variables dependientes analizadas.

DiscusiónEl estudio muestra que la asistencia a los pacientes con SPB de las extremidades en nuestro medio está muy lejos de los tiempos que transcurren en los países de nuestro entorno.

ConclusionesParece fundamental la necesidad de concienciar a la población sobre la enfermedad y recordarla entre los profesionales sanitarios, al igual que la existencia de un circuito de derivación que es necesario utilizar.

Soft tissue sarcomas (STS) are a heterogeneous group of malignant tumors which derive from mesenchymal tissue originating in the embryonic mesoderm.1,2 They account for 1% of all adult tumors and are commonly diagnosed belatedly or treated inadequately at non-specialized centers, which may entail irreparable consequences for patients and physicians. For the former, the limb rescue procedure which may have been possible through an early diagnosis and treatment may become compromised and/or, even worse, the possibility of survival may be reduced. For physicians, in addition to having to bear the burden of feeling they could have done more for the patient, they may become involved in unpleasant malpractice lawsuits.

The objective of this work is to analyze the waiting times elapsed between the start of disease symptoms and specific treatment at our Musculoskeletal Tumor Unit (MSTU). Without going into detail about the consequences of delays, which we take as a given, we aim to identify bottlenecks in the patient referral circuit and propose strategies to improve them.

Materials and methodsBetween July 1st 2006 and December 31st 2012, the MSTU of our hospital provided medical care for 112 patients with malignant soft tissue tumors. We carried out an observational, longitudinal and ambispective study of a cohort of 61 patients with previously untreated STS, including some who had undergone prior biopsies at their referring centers. All cases were managed according to the diagnosis, treatment and follow-up guidelines reflected in the clinical practice guides for the disease.3–7

Patients were collected and continuously identified from the patient registry of the MSTU. According to the ethical guidelines for research procedures, the information was obtained through revision of medical histories and was gathered over telephone interviews with patients or close relatives (in cases where the patients had passed away) conducted by one of the authors (PCR). The mean follow-up period elapsed from the first consultation at our MSTU until the date of the study or death of each patient was of 2 years (range: 11 days–6 years and 2 months). The dates considered for the calculation of the different periods elapsed in healthcare were those specified in the corresponding official documents, as well as those reported by patients regarding the start of symptoms and initial medical consultations. When this was not clearly specified and was only estimated approximately within a specific month, we considered the 15th of that month. When 2 consecutive months were referred as the approximate time of the investigated episode, we considered the 1st of the second month. All data were collected and registered by one of the authors of the work (PCR) in a data collection form designed for this study.

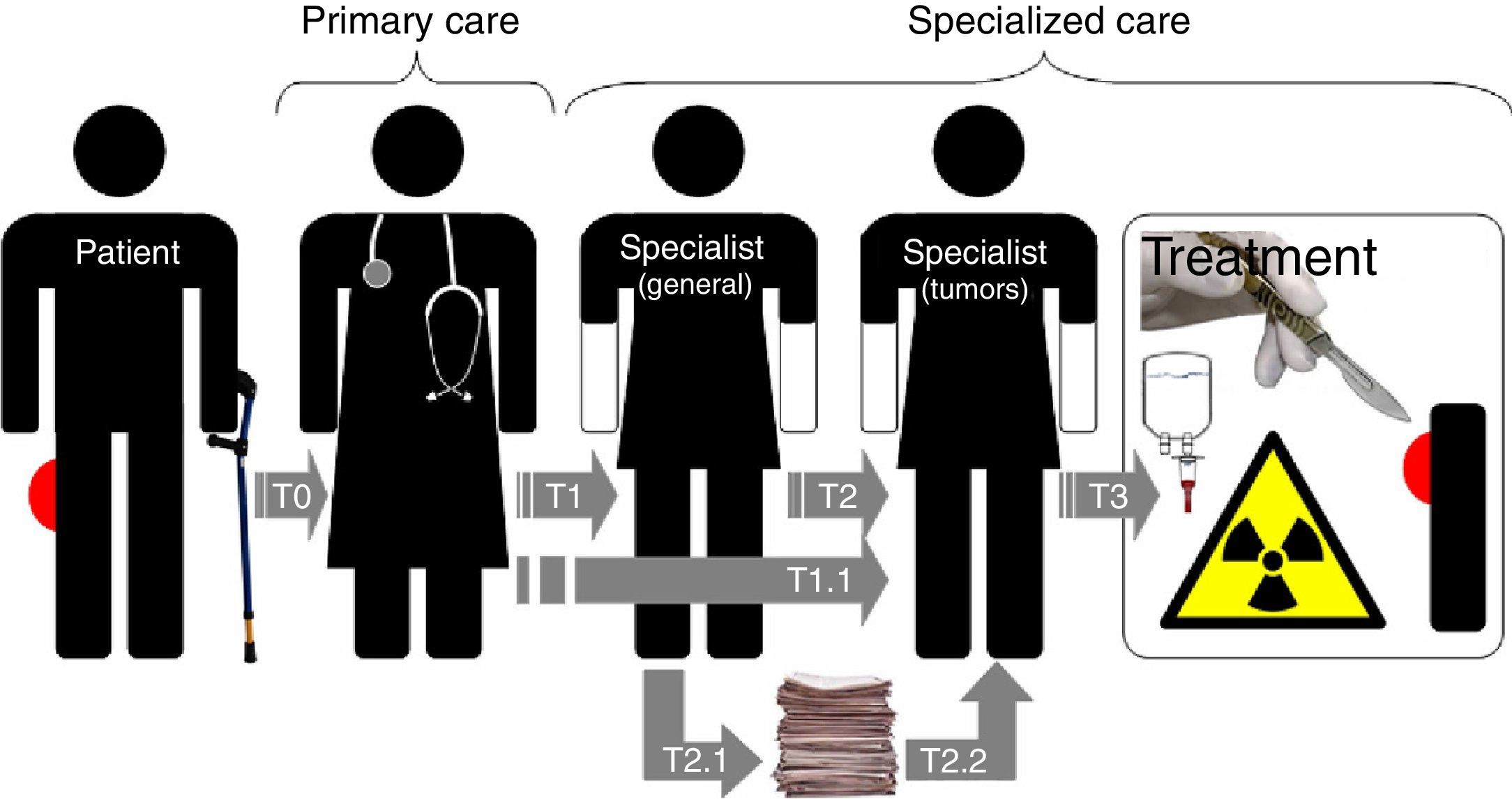

We analyzed the different times elapsed from the moment the disease became symptomatic in each patient until they were seen and began treatment at our MSTU (Tables 1 and 2, and Fig. 1). These were related to the following independent variables: a) linked to the characteristics of each patient (age above or below 65 years, gender, level of education, resident of a city with a general hospital or not, and referring healthcare area); b) related to the disease (first symptom/sign, location of the tumor in upper or lower limbs, superficial or deep location of tumor relative to the fascia, size of tumor larger or smaller than 8cm, considering this size as the major diameter of the tumor in any plane in space measured in cms in a magnetic resonance imaging [MRI] or computed tomography [CT] scan, and low or intermediate/high malignancy grade), and c) relative to the healthcare circuit followed by patients (type of first physician consulted, type of first specialist consulted and progress through the habitual healthcare circuit in the Spanish public health system: primary care physician – general traumatologist – oncological orthopedic surgeon).

Description of the variables regarding periods elapsed during healthcare of the patients in the study.

| T0 | Time elapsed from the confirmation of the first sign/symptom of the disease by the patient until the first medical consultation |

| T1 | Time elapsed from the first medical consultation for the disease until the first consultation with a specialist |

| T 1.1 | Time elapsed from the first consultation for the disease until consultation at our MSTU |

| T2 | Time elapsed from the first consultation for the disease with a specialist until consultation at our MSTU |

| T 2.1 | Time elapsed from the first consultation for the disease with a specialist until the start of the process for referral to our MSTU |

| T 2.2 | Time elapsed from the start of the process for referral to our MSTU until the first consultation at our MSTU |

| T3 | Time elapsed from the first consultation at our MSTU until the start of specific treatment for the disease |

Distribution of the patients in the series according to the variables and cutoff times considered.

| Cutoff times | T0 (%) | T1 (%) | T1.1 (%) | T2 (%) | T2.1a (%) | T2.2a (%) | T3b (%) |

| >30 days | 31 (51) | 31 (51) | 57 (93) | 46 (75) | 40 (66) | 3 (5) | 22 (36) |

| <30 days | 30 (49) | 30 (49) | 4 (7) | 15 (25) | 17 (28) | 54 (88) | 35 (57) |

| >60 days | 44 (72) | 36 (59) | 21 (34) | ||||

| <60 days | 17 (28) | 25 (41) | 36 (59) | ||||

| >90 days | 39 (64) | ||||||

| <90 days | 22 (36) |

The time variables were recoded into dichotomous variables with the following cutoff periods: periods equal to or shorter than (≤) and longer than (>) 30 days for the T0 and T1 variables; periods ≤ and > 60 days for T2 variables; and periods ≤ and >30, 60 and 90 days for T.1.1 variables.

The information was entered into a database created using Microsoft® Access 2000. Once this was revised and debugged, we exported the data to the statistical package SPSS® v.18, which we used to carry out the statistical analysis. This consisted of a descriptive analysis of the variables, calculating the frequency distribution for the qualitative variables and mean, median, standard deviation, 95% confidence interval, range, inter quartile range and maximum and minimum values for quantitative variables. We used Fisher's exact test to analyze the relationship between the waiting times recoded as dichotomous variables and the study variables. The level of statistical significance was set at α=0.05 in all cases.

ResultsResults of the characteristics of patients in the seriesThe 61 patients in the series included 31 males (51%) and 30 females (49%), with a mean age of 62 years (median: 64; SD: 17.4; 95% CI: 57.7–66.6; range: 72; minimum value: 18; maximum value: 90 years). A total of 12 patients (20%) had an educational level of high school or above, whilst the rest had basic education or none (80%). A total of 24 patients (39%) lived in cities with a general hospital, with 27 of these coming from the Leon healthcare area and the rest (56%) from other healthcare areas within the Region of Castilla y Leon, except for 1 patient who was referred from Plasencia (Region of Extremadura).

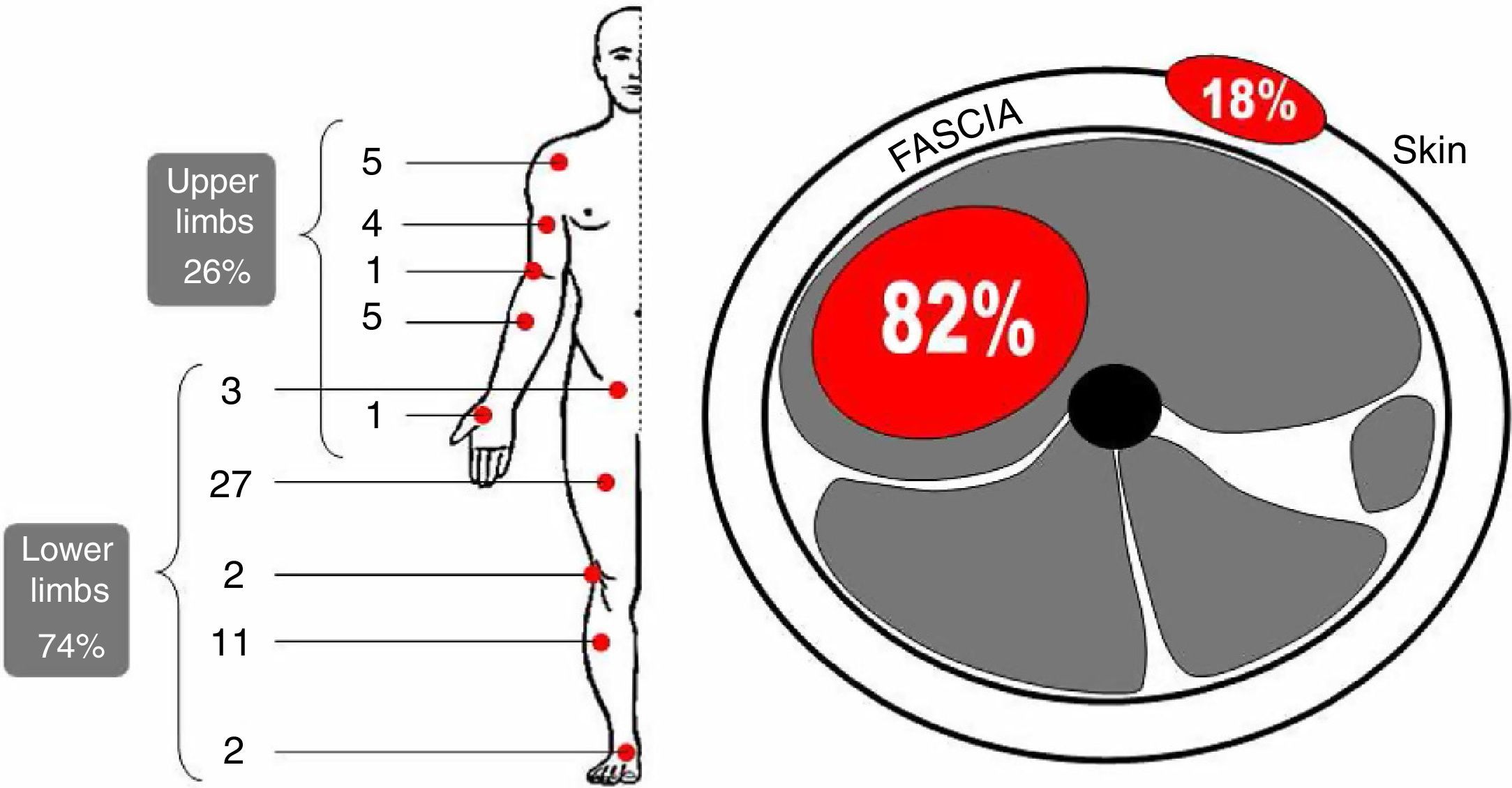

Results of the characteristics of the diseaseThere were 20 liposarcomas (33%) and 16 pleomorphic sarcomas (26%), with the remaining cases involving different histopathological types (Fig. 2). In terms of malignancy, 49 (80%) were intermediate or high grade and 12 (20%) were low grade. In terms of location, 45 (74%) were located in the lower limbs and pelvic girdle, with 27 of them in the thigh. The location of the remaining cases is represented in Fig. 3. The mean size of sarcomas was 11.3cm (range: 3.4–31cm), with 12cm (range: 3.4–31cm) among deep cases and 7.9cm (range: 4–20cm) among superficial cases. The first symptom of the disease was a bulge in 50 patients (82%), in 3 cases with pain associated to the tumor. A total of 11 cases (18%) did not report any swelling or bulge as the first sign of the disease. A total of 27 patients (44%) had died at the end of the study.

Graphic representation of the histological types in our series. LS: liposarcoma; PLS: pleomorphic sarcoma; MFS: myxofibrosarcoma; SS: synovial sarcoma; Others: 3 leiomyosarcomas, 3 malignant nerve sheath tumors, 2 dermatofibrosarcomas, 1 angiosarcoma, 1 clear cell sarcoma, 1 epithelioid sarcoma, 1 malignant giant cell tumor, 1 Ewing sarcoma and 1 extraskeletal osteosarcoma.

The first professional consulted was a primary care physician in 48 cases (79%), who referred 36 of these patients (75%) to the corresponding regional traumatologist and the remaining 12 to other specialists (4 to a general surgeon and 3 to a dermatologist). All these specialists subsequently referred patients to a traumatologist or, in 2 cases, directly to our MSTU. In 13 cases (21%), the first professional consulted was not the primary care physician (an emergency room physician in 7 cases). Three patients were attended by three different physicians for the same disease. In 36 cases (59%), patients were treated by the primary care physician of their healthcare center and also by a general traumatologist, before being referred to our MSTU. The values of the waiting times elapsed from the first manifestation of the disease until its treatment are shown in Table 3. Figs. 4 and 5 present 2 cases of the series as examples.

Description of the values of times elapsed, in days, during the medical care of the patients in the series.

| Times | Mean | Median | Standard deviation | Interquartile range | Minimum value | Maximum value | Confidence interval* (mean) |

| T0 | 289 | 31 | 893 | 125.50 | 0 | 5463 | 42–388 (215) |

| T1 | 80 | 31 | 147 | 53.00 | 0 | 739 | 42–127 (85) |

| T1.1 | 253 | 107 | 562 | 95.00 | 2 | 4005 | 111–441 (276) |

| T2 | 173 | 67 | 538 | 68.50 | 0 | 3943 | 32–350 (191) |

| T2.1a | 169 | 51 | 556 | 62.00 | 1 | 3937 | 20–338 (179) |

| T2.2a | 12 | 10 | 11 | 10.00 | 0 | 49 | 9–15 (12) |

| T3b,c | 46 | 22 | 69 | 28.00 | 1 | 414 | 28–67 (47) |

Calculations for 57 cases, as the data regarding the start of the process for referral to our MSTU were not known in 4 cases.

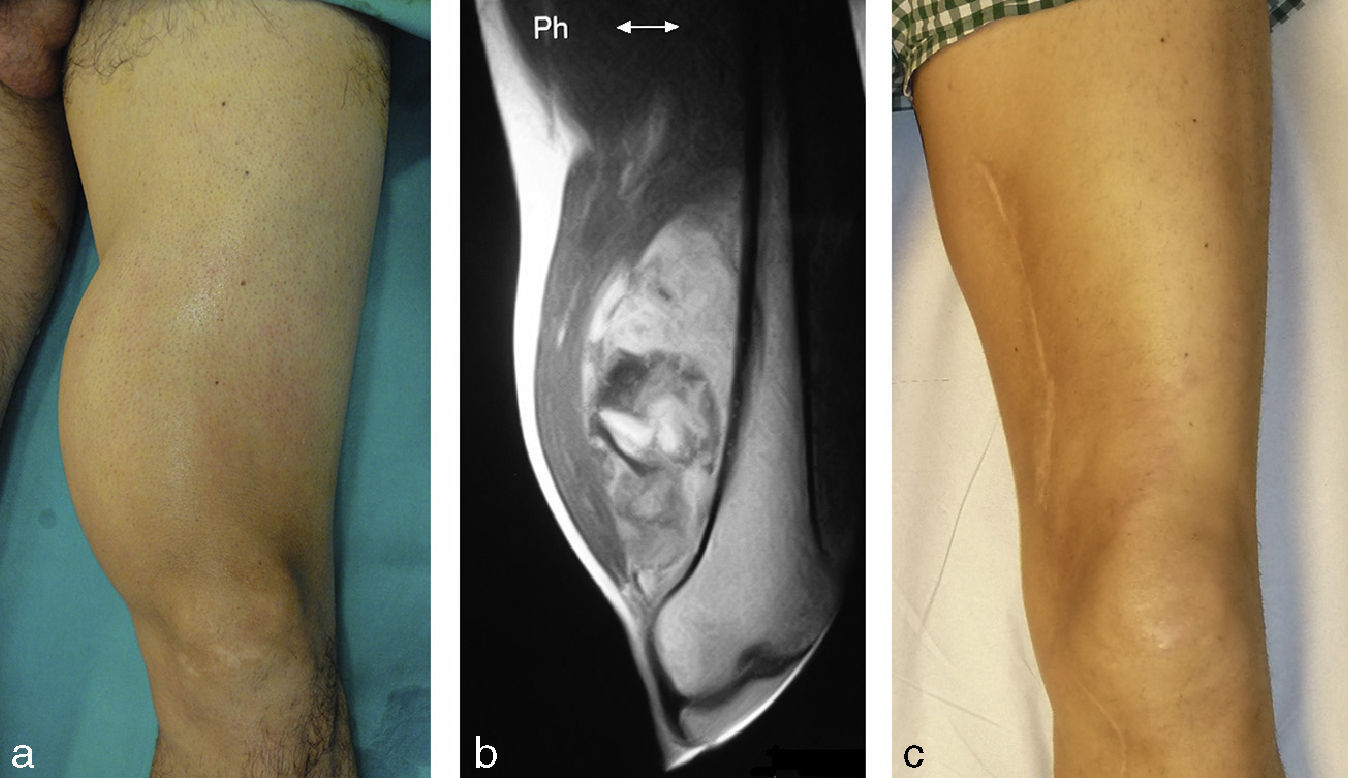

Deep liposarcoma in a 40-year-old male patient in the series, with higher education, who consulted the primary care physician 15 years (T0) after starting to perceive a bulge with a very slow growth in the left thigh (a). The physician referred him to a general surgeon, who saw him after 33 days (T1) and he was then referred to and seen at our consultation on the same day (T2: 0 days). The maximum diameter of the tumor measured in an MRI scan was 14cm (b). The surgical treatment of the tumor, after biopsy and surgical planning, took place 28 days later (T3). Two years after the resection and postoperative radiotherapy (c).

Superficial leiomyosarcoma in a 49-year-old female patient, with basic education, who attended consultation with her primary care physician 630 days (T0) after starting to perceive a bulge with progressive growth in her left thigh (a). She was referred by the physician to the area traumatologist, who saw her after 21 days (T1) and conducted an incisional biopsy. The patient was referred to and seen at our consultation 73 days after the first specialized consultation (T2), with the referral process being completed 3 days earlier (T2.2). The major diameter of the sarcoma was of 8.8cm (b). Its surgical treatment took place 15 days after the consultation at our MSTU (T3). Appearance of the thigh after extensive resection and reconstruction using a free skin graft and postoperative radiotherapy (c).

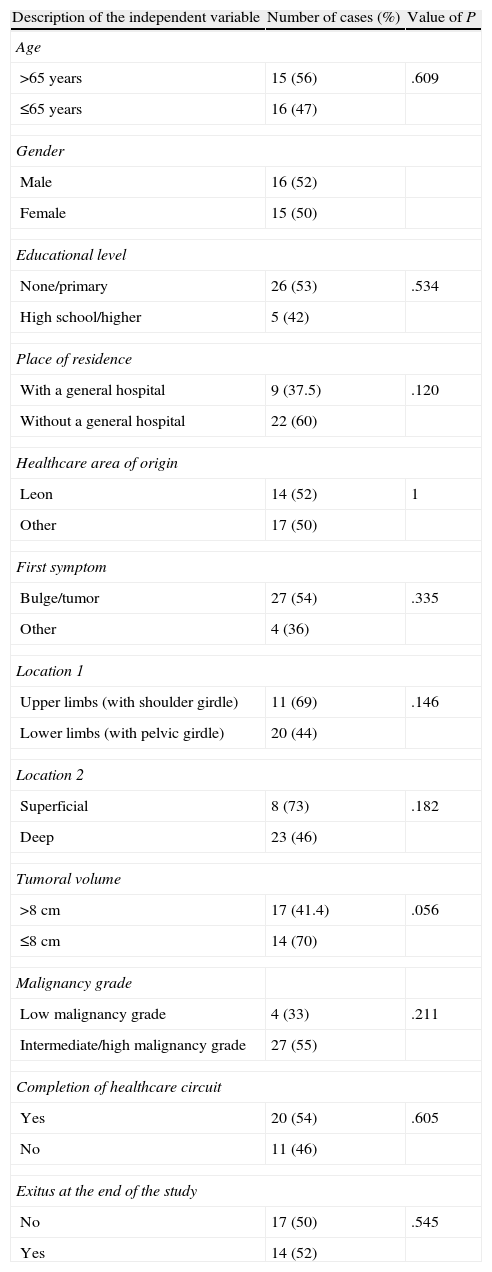

Very few variables displayed a statistically significant relationship with the care times analyzed. If we consider the frequency of patients with a T0 time over 30 days, we can observe a difference approaching statistical significance regarding tumor size: 70% of patients with tumors of 8cm or less had a T0 longer than 30 days, compared to 41.4% of those who had tumors larger than 8cm (P=.056). In total, 60% of patients who resided in towns without a general hospital also presented a T0 longer than 30 days, compared to 37.5% of those who lived in cities with a hospital (P=.120). Regarding location, 69% of patients with tumors in the upper limbs presented a T0 over 30 days, compared to 44% among those with tumors located in the lower limbs (P=.146). We also observed that 73% of patients with superficial tumors presented a prolonged T0, compared to 46% among patients with deep tumors (P=.182) (Table 4).

Summary of contingency tables of the relation between T0>30 days and the independent variables studied.

| Description of the independent variable | Number of cases (%) | Value of P |

| Age | ||

| >65 years | 15 (56) | .609 |

| ≤65 years | 16 (47) | |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 16 (52) | |

| Female | 15 (50) | |

| Educational level | ||

| None/primary | 26 (53) | .534 |

| High school/higher | 5 (42) | |

| Place of residence | ||

| With a general hospital | 9 (37.5) | .120 |

| Without a general hospital | 22 (60) | |

| Healthcare area of origin | ||

| Leon | 14 (52) | 1 |

| Other | 17 (50) | |

| First symptom | ||

| Bulge/tumor | 27 (54) | .335 |

| Other | 4 (36) | |

| Location 1 | ||

| Upper limbs (with shoulder girdle) | 11 (69) | .146 |

| Lower limbs (with pelvic girdle) | 20 (44) | |

| Location 2 | ||

| Superficial | 8 (73) | .182 |

| Deep | 23 (46) | |

| Tumoral volume | ||

| >8cm | 17 (41.4) | .056 |

| ≤8cm | 14 (70) | |

| Malignancy grade | ||

| Low malignancy grade | 4 (33) | .211 |

| Intermediate/high malignancy grade | 27 (55) | |

| Completion of healthcare circuit | ||

| Yes | 20 (54) | .605 |

| No | 11 (46) | |

| Exitus at the end of the study | ||

| No | 17 (50) | .545 |

| Yes | 14 (52) | |

The variables with greatest connection with a T1.1 over 30, 60 and 90 days, were completing the healthcare circuit and survival at the end of the study. Up to 73% of patients who completed the circuit waited more than 90 days, whereas 50% of those who did not, waited less, although the difference was not significant (P=.102). Up to 74% of patients who were alive at the end of the study had waited more than 90 days, compared to 52% of the patients who died (P=.109) (Table 5).

Summary of contingency tables of the relation between T1.1>90 days and the independent variables studied.

| Description of the independent variable | Number of cases (%) | Value of P |

| Age | ||

| >65 years | 16 (59) | .595 |

| ≤65 years | 23 (68) | |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 20 (65) | .567 |

| Female | 19 (63) | |

| Educational level | ||

| None/primary | 31 (63) | .553 |

| High school/higher | 8 (67) | |

| Place of residence | ||

| With a general hospital | 13 (54) | .276 |

| Without a general hospital | 26 (70) | |

| Healthcare area of origin | ||

| Leon | 18 (67) | .791 |

| Other | 21 (62) | |

| First symptom | ||

| Bulge/tumor | 32 (64) | 1 |

| Other | 7 (64) | |

| Location 1 | ||

| Upper limbs (with shoulder girdle) | 12 (75) | .370 |

| Lower limbs (with pelvic girdle) | 27 (60) | |

| Location 2 | ||

| Superficial | 9 (82) | .299 |

| Deep | 30 (60) | |

| Tumoral volume | ||

| >8cm | 24 (59) | .263 |

| ≤8cm | 15 (75) | |

| Malignancy grade | ||

| Low malignancy grade | 9 (75) | .509 |

| Intermediate/high malignancy grade | 30 (61) | |

| Completion of healthcare circuit | ||

| Yes | 27 (73) | .102 |

| No | 12 (50) | |

| Exitus at the end of the study | ||

| No | 25 (74) | .109 |

| Yes | 14 (52) | |

The variable most related to a T1 over 30 days was survival at the time of the study: 62% of survivors presented a T1 over 30 days, compared to 37% of those who died before the end of the study (P=.073). There were no variables related to a T2 over 30 days with a value of P<.2. The variable which was most related to a waiting time over 60 days was completing the normal healthcare circuit: 70% of patients who completed it had a T2 over 60 days, compared to 42% among those who did not complete it (P=.035). The variables which were most related to a T2.1 greater than 30 days were the original healthcare areas of patients and their survival at the end of the study. In total, 87.5% of patients from the province of Leon had a T2.1 over 30 days, compared to 58% among those who came from other healthcare areas in the Region of Castilla y León (P=.020). On the other hand, 81% of patients who were alive at the end of the study had a T2.1 over 30 days, compared to 58% among those who did not survive (P=.083). None of the variables approached statistical significance when analyzing a T2.1 over 60 days, T2.2 over 30 days or T3 over 30 days.

DiscussionSTS are malignant tumors derived from extraskeletal mesenchymal tissue, including adipose, fibrous, nervous and muscular tissue, as well as blood and lymph vessels. Their clinical behavior is variable, depending on the age of the patient and the location and histological type of the tumor. Survival at 5 years is estimated at about 50–60% of cases.1,2 The cases in our series did not present any unusual epidemiological, histopathological or clinical peculiarities, except that their size at the time of diagnosis was considerably larger than the average for the countries in our environment, around 9cm.8,9 The mean size of the sarcomas in our series reached 11.3cm, with 7.9cm in superficial cases and 12cm in deep cases.

According to the incidence rates of this disease, 2–4 STS are diagnosed in the limbs for every 100,000 inhabitants per year. This allows us to estimate that primary care physicians will attend 1 case every 24 years and general specialists will see very few during their healthcare practice.10 Knowledge of the existence and significance of such an infrequent and relevant disease, which is often unknown by patients, is essential for an opportune and adequate care,3,5–7,11,12 which, in turn, will determine the prognosis of the disease.13,14 The adequate form of treatment is related, firstly, to the place where this should take place; at specialized referral centers, where the diagnosis will be more certain in relation to the biopsy12,15 and its pathological interpretation,16 as well as in relation to the oncological and functional therapeutic results.17 Regarding the times, the sooner the treatment for STS is started, the better the prognosis. Not complying with any of the aforementioned places, the health of the patient at risk increases costs18 and exposes professionals to scrutiny by society, patients and their families, as well as to possible malpractice lawsuits.

Rapid referral of a patient with STS to a specialized center requires a knowledge of the suspicion signs of the disease, which are mainly bulges, usually deep and slightly or not painful, over 5cm in size and which grow or reappear after excision.8 The existence of a rapid and simple referral circuit in the context of a fluid relationship between healthcare professionals is another key element.17,19

Regarding the mentioned circuit, one of the objectives of the clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of STS is to reduce waiting times from the moment the disease becomes symptomatic until the start of treatment. Specific studies do not reflect uniformity among the times recorded, as this is not present either in the circuits followed by patients, who may reach the specialized unit after referral by a primary care physician or another general specialist, sometimes with intermediate stages. For example, in the series by Rowbotham et al.,7 36% of patients were referred by a primary care physician, whilst the remaining 64% came from other hospital specialists. These were normally traumatologists or general surgeons. Interestingly, the latter generally referred patients who had undergone more previous procedures, usually inadequate, than the former. Up to 74% of patients in the series by George and Grimer20 attended the initial consultation with their primary care physician with, at least, 1 of the findings listed in urgent referral guidelines; and only 2 (4%) were referred directly to the tumor unit, whilst 21 (43%) were referred to secondary centers to conduct additional tests.

In our Public Healthcare System the care circuit is clearly defined, with primary care physicians being the entry point to the system, and emergency services acting as a complement for urgent cases. Either of these stages, when required, should refer patients to general specialists who, in turn, should do the same for diseases requiring a more specific care, as in the case of patients with STS. In our study, the first professional consulted was a primary care physician in 79% of cases and a specialist at the emergency service in 11%, thus highlighting that the correct circuit was only followed by 59% of patients. This means that 41% followed a different circuit because they initially consulted a specialist other than their primary care physician (21%) or because they were referred by their primary care physician to a specialist other than a traumatologist (20%).

The question of the periods elapsed in the care circuit for STS patients is vitally important since, in addition to affecting morbidity, it has been described as a statistically significant predictive factor of metastasis at the time of diagnosis and patient overall survival,21 although this observation has not been shared by all authors. In fact, Rougraff and Lawrence22 considered that the time of diagnosis in high grade STS patients did not predict the oncological result, which would be more dependent on other biological factors of the disease. Moreover, paradoxically, in some cases a long delay in care has been associated with a good prognosis, although these cases would involve tumors with a low grade of malignancy.8

In any case, the diagnostic delay considered significant is difficult to quantify,7 and studies on this issue tend to find the limitations inherent to a difficulty in identifying the cause of the delay, which is often multifactorial, as well as the lack of a group of cases diagnosed incidentally to serve as a control group. In general, accepting that delays tend to occur before patients reach the referral center,23 we can distinguish between delays attributed to patients and delays attributed to physicians. The former takes place between the first symptom and the first medical consultation, whereas the latter takes place from the time of the first medical consultation until the patient reaches the oncological unit.

In countries with developed healthcare systems, the mean delays attributed to patients range between 1 and 4 months, whilst those attributed to physicians range between 1 and 3 months.15,20 In the series by Johnson et al.,24 the time elapsed from the presentation of the disease until consultation with the specialist was less than 1 month in half of the patients. In the series by Malik et al.,25 all patients with sarcomas began treatment within 2 months after being referred, regardless of the circuit followed. In the series by Smith et al.,9 the times elapsed from the start of the symptoms until patients were treated at the unit for STS tumors in upper and lower limbs, thorax and pelvis were 26, 25, 20 and 28 weeks, respectively.

In all the cases in our study, the mean time elapsed from the onset of the first symptoms of the disease until the first medical consultation was slightly over 9.5 months, whilst the period elapsed from this first consultation until the first consultation at our MSTU was nearly 8.5 months. Within this period, the time until the first specialized consultation was 80 days, whilst the remaining period of over 5 months represents the time from that consultation to our own. If we divide that time interval by the time taken to process the referral to an oncological unit, we can see that most of it (98%) took place before the referral, so only 12 days elapsed until consultation at our MSTU. In other words, regardless of the fact that the series included cases very far from the mean which could have distorted the results, it seems clear that the times were very distant from those published, and that patients waited too long to attend consultation for the disease. In addition, the period from the first medical consultation until the first consultation at a specialized unit was also too long. The period elapsed from the first specialized consultation until the start of referral processing was especially striking.

The reasons for an excessive delay before the first medical consultation probably involve a lack of specific or severe symptoms, which the patients did not respond to. In our study, with a cutoff point of 30 days, the longest periods were mainly related to cases with sizes below 8cm, in accordance with expectations and published reports. The fact that patients who resided in towns without a general hospital also delayed the first medical consultation could be more related to the influence of the hospital on the awareness of the disease among the population than a lower educational level, whose influence was also studied and ruled out. The fact that patients with tumors located in the upper limbs and with superficial sarcomas attended consultation later is probably connected to an erroneous perception of the disease by the population.

According to Johnson et al.,24 the reasons for an excessive delay in reaching the specialized unit after the first medical consultation are the responsibility of the medical professional and are related to a lack of suspicion of the disease, leading to confusion with other processes.19 In our study, with cutoff points at 30, 60 and 90 days and without investigating the specific reason for the delay, the longest delays were associated to patients who had followed the usual referral circuit and to those with the longest survival at the end of the study. Far from being surprising, the interpretation of these findings confirms the suspicion that the circuit is slow and should be improved, as it is not normal that those patients who do not follow it are seen sooner (most likely because they go to emergency services where the referral process is accelerated). The fact that those patients with greater survival waited longer for therapy is explained by the fact that these patients had a less severe disease at the time of diagnosis.

A third entity in the responsibility for delay, which has hardly been mentioned in the literature, could be the system itself and its inherent rigidity. Although we might be tempted to place blame on it, especially in the current context of crisis and budget cuts which increase healthcare load, it does not appear that it could be the reason for delays once the disease is suspected. The mean value of 12 days elapsed from the start of the referral process of patients to our MSTU proves that, at least in this last part of the circuit, there is no administrative responsibility.

Considering the prognostic factors of STS and the fact that nothing can be done to influence many of them, an early diagnosis would lead to a smaller size at presentation, which would facilitate a conservative treatment and would improve the prognosis of the disease,8,26 in spite of the fact that no significant correlation has been proven between the duration of symptoms and size,8 nor between size and a belated diagnosis of the tumor.27 Regardless of this point, size as the single criterion for referral of patients with soft tissue lesions to a reference center is arguable, since it has been proven that 10% of malignant lesions can measure less than 5cm, and that over half of benign lesions can measure over 5cm.7

The measures which should be adopted and maintained over time to improve care for STS patients include educating the general population about the alert signs and symptoms of the disease, as well as the importance of consulting a physician early; training of medical staff to improve suspicion of the disease and its correct treatment, which should also be extended to medical students; and the creation of guidelines and circuits, which should be publicized, for the referral of patients to adequate centers.20 Accepting that awareness campaigns for this disease targeting the population would not have the same effect as, for example, those related to breast cancer, and in fact would increase healthcare load, as well as the fact that urgent referral centers have several shortcomings, such as their proven performance and the interference with emergency healthcare services which should be dedicated to patients referred by other routes,25,28–30 these measures would improve the deficient reality identified.

Our work has several limitations, although in spite of them we believe that it proves that care for patients with STS of the extremities in our environment could be improved with regards to the healthcare circuit and philosophy. Firstly, it is a retrospective study. Secondly, the sample size is relatively small, thus decreasing the power of the statistical tests employed. This means that, although we may have observed important clinical differences which would probably be statistically significant, they could be very difficult to detect (false negatives). Thirdly, inherently to the disease being studied, the cases were heterogeneous in their histological type and grade of malignancy. In fourth place, the population studied was already biased because it comprised patients with a diagnosis of sarcoma at a referral unit which does not receive all the sarcomas diagnosed in the Region of Castilla y Leon. Furthermore, the geographic, demographic and possibly socioeconomic and cultural peculiarities are not the same as in other political Regions in our country. In fifth place, the dates employed in the study were mainly based on the memories of patients regarding their disease, which are always subject to bias. In order to minimize this, the dates recorded in the clinical history of patients were compared with those asked from patients (or their relatives when patients had passed away), ensuring that there were no significant differences. In sixth place, we did not study aspects which could have been of interest, such as details about the delays of patients regarding the first medical consultation or the relationship between delays and treatment results, which we considered demonstrated. Lastly, we did not carry out a multivariate analysis, which could have proven an interrelationship and exponentiation of the variables.

In conclusion, the waiting times in our environment, as well as the volume of STS at diagnosis, are excessively long and large, respectively, especially until the start of the referral process for patients to our MSTU. The needs to increase awareness of the disease among the population and also to remind healthcare professionals about it seem essential. Likewise, the existence of a necessary and mandatory referral circuit should also be highlighted.

Level of evidenceLevel of evidence II.

Ethical responsibilitiesProtection of people and animalsThe authors declare that this investigation did not require experiments on humans or animals.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their workplace on the publication of patient data and that all patients included in the study received sufficient information and gave their written informed consent to participate in the study.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare having obtained written informed consent from patients and/or subjects referred to in the work. This document is held by the corresponding author.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Please cite this article as: Ramos-Pascua LR, Sánchez-Herráez S, Casas-Ramos P, Izquierdo-García FJ, Maderuelo-Fernández JA. Circuito de asistencia a pacientes con sarcomas de partes blandas de las extremidades: un tortuoso y lento camino hasta las unidades de referencia. Rev Esp Cir Ortop Traumatol. 2014;58:160–170.

This work received the SECOT Foundation award for Clinical Research in Traumatology and Orthopedic Surgery in 2013.