Questionnaires measuring health-related quality of life are difficult to perform and obtain for patients and professionals. Computerised tools are now available to collect this information. The objective of this study was to assess the ability of patients undergoing total knee replacement to fill in health-related quality-of-life questionnaires using a telematic platform.

Material and methodsNinety eight consecutive patients undergoing total knee arthroplasty were included. Participants were given an access code to enter the website where they had to respond to 2 questionnaires (SF8 and the reduced WOMAC), and 3 additional questions about the difficulty in completing the questionnaires.

ResultsA total of 98 patients agreed to participate: 45 males and 53 females (mean age 72.7 years). Fourteen did not agree to participate due to lack of internet access. Of the final 84 participants, 50% entered the website, and only 36 answered all questions correctly. Of the patients who answered the questionnaire, 80% were helped by a relative or friend, and 22% reported difficulty accessing internet.

ConclusionThe use of telematic systems to respond to health-related quality of life questionnaires should be used cautiously, especially in elderly population. It is likely that the population they are directed at is not prepared to use this type of technology. Therefore, before designing telematics questionnaires it must be ensured that they are completed properly.

La realización y obtención de cuestionarios de calidad de vida relacionada con la salud por el paciente y el profesional es complicada. Actualmente, disponemos de herramientas informáticas para recoger esta información. Nuestro objetivo fue evaluar la capacidad de los pacientes intervenidos de prótesis total de rodilla para rellenar cuestionarios de calidad de vida relacionada con la salud, utilizando una plataforma telemática.

Material y métodosFueron incluidos 98 pacientes consecutivos intervenidos de artroplastia total de rodilla. A los que aceptaron participar en el estudio se les solicitó responder, en una página web, a 2 cuestionarios de calidad de vida relacionada con la salud (SF8 y WOMAC reducido) y 3 preguntas adicionales de opinión sobre dichos cuestionarios.

ResultadosNoventa y ocho pacientes (45 hombres y 53 mujeres), con una media de edad de 72,7 años. Catorce no aceptaron participar por no disponer de acceso a Internet. De los 84 pacientes que aceptaron, el 50% entró en la página web, de los cuales solamente 36 contestaron correctamente a todas las preguntas. De estos, el 80% fue ayudado por un familiar o amigo y el 22% refirió dificultades para acceder a Internet.

ConclusiónLa utilización de sistemas telemáticos para responder a cuestionarios de calidad de vida debe ser usada de forma cautelosa, especialmente en población de edad avanzada. Probablemente, la población a la que va dirigida no está preparada para utilizar este tipo de tecnología. Por ello, antes de diseñar cuestionarios telemáticos debemos asegurarnos de si serán debidamente cumplimentados.

A wide variety of methods accepted by the scientific community is currently available for objectively measuring the outcome of procedures in orthopaedic and trauma surgery (OTS). The comparative efficacy of available alternative procedures may also be evaluated using these measurements.

The importance of recording data on clinical outcome and tests resides in its potential use for carrying out an appropriate pre- and post-operative evaluation of the different procedures.1,2 Over and above the standard radiographic and functional parameters in our speciality, efforts are also made to collect data on patients’ quality of life, using self-assessment questionnaires which refer to health-related quality of life (HRQOL).3

These questionnaires must be reliable and quantify the impact of medical interventions on patients’ quality of life in the most objective and accurate manner possible, providing a starting point from which to assess and improve our activity. Furthermore, they help to respond to public demand in order to achieve relevant outcomes. Finally, they provide a tool for weighing up the cost–benefit of these interventions; without them a significant part of scientific literature would lose its validty.1–4

Patient's quality of life assessment is not a standard procedure in our speciality, not least because of the difficulty in collecting data due to lack of time and familiarity with the questionnaires. The desire therefore exists to develop strategies based on the use of communication technologies in order to respond to this need.5,6

This study was designed for patients scheduled to undergo total knee replacement surgery (TKR), the main objective being to evaluate their ability to respond telematically in a satisfactory manner to HRQOL questionnaires. The secondary objective was to create a valid and reliable electronic platform so that these HRQOL measures could be routinely obtained in normal clinical practice.

Material and methodsA unicentric, transversal observational study was carried out on a consecutive cohort of patients scheduled to undergo TKR in the Hospital of Santa Creu y Sant Pau (University Hospital of Barcelona). The study protocol was approved by our hospital's ethical committee of clinical research (code number: IIBSP-OUT-2012-01).

Patients undergoing TKR were selected because this is one of the most standard surgical procedures in our OTS department, and because it has a high impact on patients’ quality of life.7 It should be taken into consideration that this type of patient is highly affected by their condition, causing them limitations in their daily lives, and we therefore believed they would be more than willing to participate in the study.

Patients were recruited between March 2012 and March 2013. During the preoperative outpatient visit to the OTS department, patients were informed in detail about the study, and they were offered the possibility of participating, regardless of whether they had access to the internet or not. Information was verbally communicated, always by the same person (co-author of the study), and patients were given a detailed information sheet about the study, for which their informed consent was obtained.

Those patients who refused to take part in the study were asked to provide details of their reasons, without this being detrimental or harmful in any way to their treatment or clinical follow-up of their condition.

A website was contracted for the survey. During the above-mentioned preoperative visit, those patients who decided to participate were given the access code to the website (www.surveymonkey.com/TKRSANTPAU) and the private user code to respond to 2 HRQOL questionnaires, in addition to a survey for evaluating their perception of the difficulty of accessing HRQOL telematically. They were asked to fill in the questionnaires prior to surgery.

From among the great variety of available questionnaires we chose those most regularly used in OTS8,9 (the shortened versions): the WOMAC questionnaire of 7 items validated in Spanish,2,3,10,11 and the general SF8 quesionnaire,8,12 to assist in its completion.2,4

The additional survey consisted of 3 questions aimed at assessing the degree of difficulty in accessing a computer with Internet connection, the need for help to go on-line and to fill in the questionnaires, and the perception of the level of difficulty of the questions in both questionnaires.

Prior to the study, 10 patients completed a pilot test, aimed at detecting possible problems or errors in the telematic platform where the questionnaires would be filled out, and also the viability of the study.

The information recorded in the telematic platform was collected and analysed, with 2 possible patient categories being determined, those who were “capable” and those who were “incapable” of completing all the questions on the questionnaires, regardless of the number of attempts made and whether they had received external assistance in completing them. This definition is based on the premise that the HRQOL are only useful when all items are completed. In addition, the patients classified as “incapable” were divided into 3 subcategories: (1) those patients who since the beginning had decided not to participate in the study; (2) those who after accepting, had not accessed the website; and (3) those who accessed the website but did not complete the questionnaires.

Once the study came to an end we contacted the “incapable” patients who had initially consented to participate (corresponding to categories 2 and 3), to find out the reason why they had not been able to complete the questionnaires.

All data were collected anonymously and treated confidentially using the telematic platform. They were subsequently evaluated by the epidemiological department in our hospital.

Statistical analysisAccording to our hypothesis, and assuming a priori a response rate of 80% and precision rate of 8%, the sample size was fixed at 97 patients. We decided to include all consecutive patients assessed in the preoperative TKR visits from March 2012 up to the completion of an “n” of 100 patients.

The statistical programme SPSS was used for analysis. Patient percentages in each category (“capable” and “incapable”) and in the established subcategories were calculated. These were compared using the Chi-squared test.

For the comparison of the patients’ mean age, an analysis was performed using Student's t-test for independent samples and equal variances.

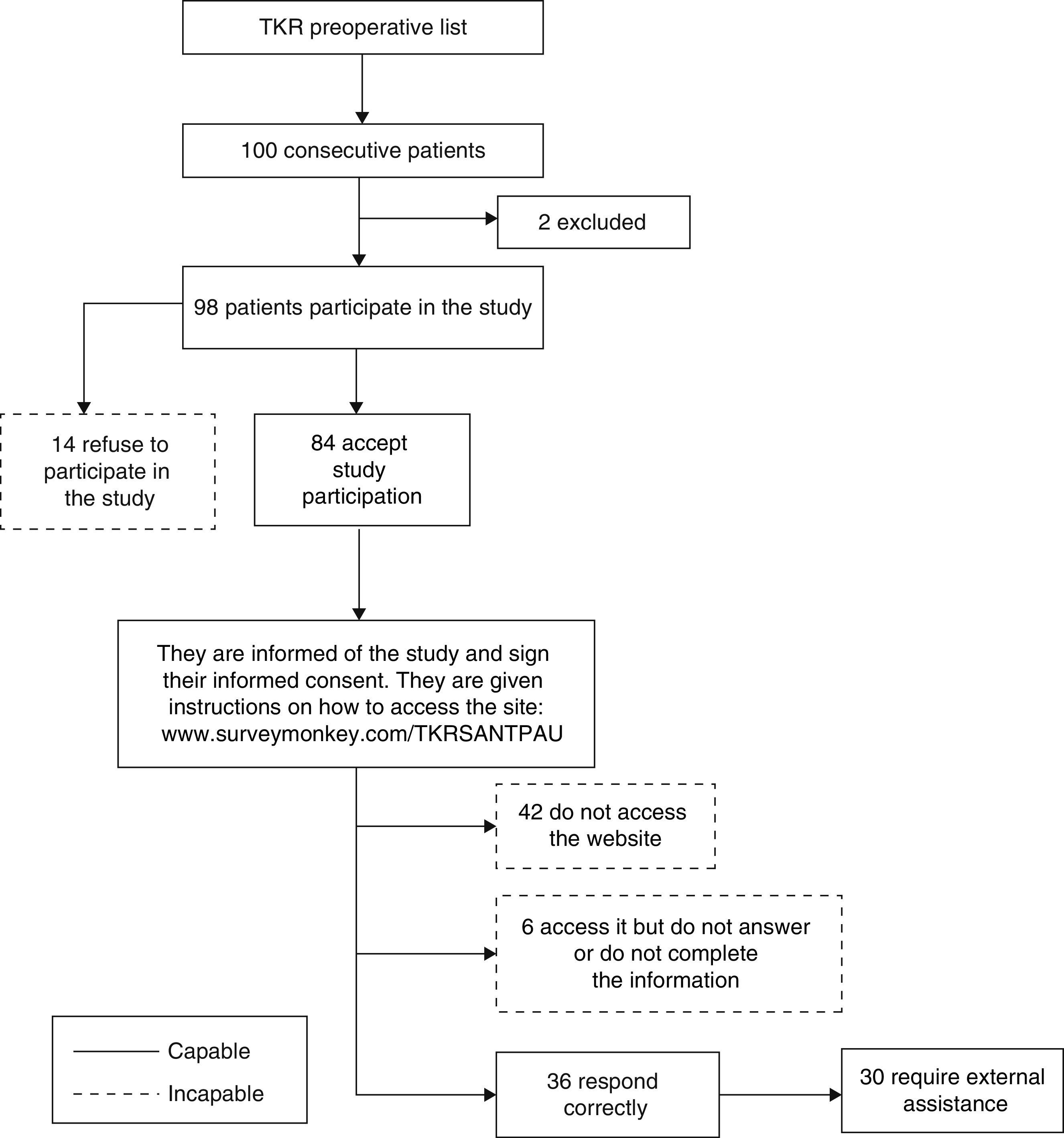

ResultsOf the 100 cases initially selected, 2 were subsequently excluded because they were repeated (they were erroneously given 2 codes), with 98 valid patients in total. Mean patient age was 72.7±7.02, with a range between 49 and 87 years of age. Of these, 14 refused to participate, indicating as their main reason the impossibility of accessing the Internet, whilst 84 patients (85.7%) did accept. Out of these, 42 patients (50%) finally indicated that they would participate but then later did not access the website, 6 gained access to the website but did not know how to respond or only partially responded to the surveys and the remaining 36 patients responded completely to the questionnaires (Fig. 1). Consequently, only 37% of the participants were considered capable of satisfactorily responding telematically to the survey, as opposed to the 80% assumed in our initial hypothesis.

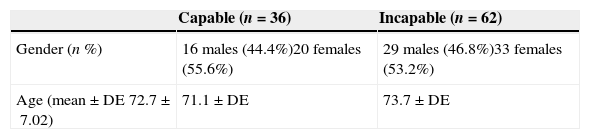

The mean age of the 36 capable patients was 71.1 (8.3), compared with 73.7 (±) of the incapable ones; this difference was not statistically significant (P=0.085). There were no significant differences regarding gender either (37.7% females and 35.6% males, P=0.823) (Table 1).

Of the 62 patients (63.2%) considered incapable, only 14 (22.6%) stated in the preoperative visit that they would not participate in the study because they had no Internet access. Of the remainder who did agree to participate in the study, 42 (43%) did not access the Internet and the response of 6 (9.6%) was incomplete. Of the 42 patients who had accepted to participate in the study but did not access the Internet, 19 (30.6%) reported they had difficulties in doing so, 9 (14.5%) forgot to do the survey despite having access to the Internet, 2 did not know how to get onto the website, one changed their mind and decided not to participate and one stated that the website did not work. It was not possible to contact another 10 patients to find out the reason why they had not participated in the survey.

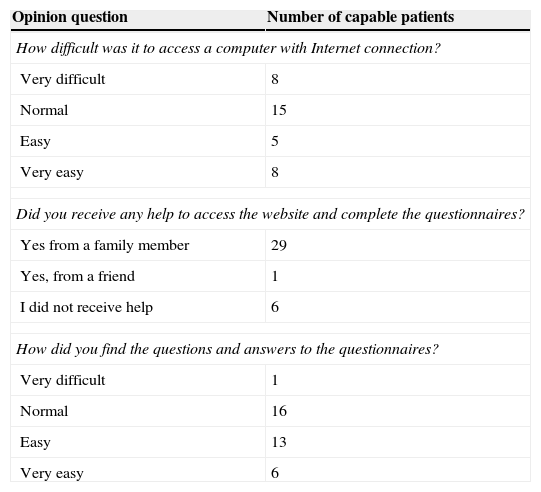

The 36 who were capable of satisfactorily completing the questionnaires, responded to the additional evaluation survey on the difficulty of access to the website and its content, and whether they required help in completing it. Of these, 28 (77.8%) indicated that responding telematically to the survey presented no major difficulty for them (15 responded normal, 5 easy and 8 very easy). A great majority (30) indicated they had received help from a family member. With regard to survey content, only one patient stated that they had found it very difficult. Finally, 27 (75%) completed the survey at a single attempt (Table 2).

Results of opinion polls regarding the difficulty in undertaking the study (n=36).

| Opinion question | Number of capable patients |

|---|---|

| How difficult was it to access a computer with Internet connection? | |

| Very difficult | 8 |

| Normal | 15 |

| Easy | 5 |

| Very easy | 8 |

| Did you receive any help to access the website and complete the questionnaires? | |

| Yes from a family member | 29 |

| Yes, from a friend | 1 |

| I did not receive help | 6 |

| How did you find the questions and answers to the questionnaires? | |

| Very difficult | 1 |

| Normal | 16 |

| Easy | 13 |

| Very easy | 6 |

Of the patients who underwent TKR in our hospital, a very much lower percentage than expected were capable of satisfactorily responding telematically to the quality of life questionnaires (36.7%), despite the fact that the majority of patients stated they had Internet access. For a variety of reasons, approximately one-quarter of the participants were incapable of completing the questionnaires despite having Internet access. In our study, although 61.5% reported they had access to the Internet, the majority required external aid to complete the questionnaires, and a cultural component therefore came into play which we had not evaluated regarding the availability or predisposition of family members and/or friends to help the survey participants.

One possible explanation for the low rate of completion of the telematic survey in our study could be the advanced age of the patients (mean age of 72.7 years). According to the National Institute of Statistics,16 in this age range, the percentage which accessed Internet in the last month was 12.9%, as opposed to 92.9% of the population aged between 16 and 24 or 82.8% of those aged between 25 and 34. This indicates a marked negative tendency to use the Internet as one gets older. It is possible that the outcome would have been different in other pathologies in younger patients.

Despite the above, we were unable to observe any differences regarding age or gender which could explain the differences between the patients who were capable and incapable of satisfactorily completing the questionnaires. Other variables of potential interest such as educational or socio-economic level were not evaluated, since no information was available in this regard.

With the appearance of new technologies and the extension of Internet usage, new systems have been established for self-completion of HRQOL questionnaires telematically.6,13 Collection of this valuable information is generally difficult and is inconvenient for professionals, especially because of the huge amount of time and resources required, and because they are not accustomed to it, many orthopaedic surgeons choose not to do so in the majority of cases.3,15 It was therefore assumed that using the Internet would improve completion.

Notwithstanding, according to Keurentjes et al.,17 there is a clear preference for patients who are to undergo knee and hip replacement operations to respond to questionnaires in paper format (86.8% and 81.8% respectively). However, we consider that for our specialty, although patients may have this preference, it would be feasible for them to be equally capable of responding to surveys telematically, especially bearing in mind increasing Internet usage.

By using this technology, information is directly introduced by the patient, reducing the time they spend in the surgery and avoiding human transcription errors.

It has been shown that patients familiarised with the use of these technologies respond to telematic questionnaires in less time than written or telephone ones. Help windows may be added to facilitate comprehension, providing additional information in response to possible doubts. Moreover, periodic reminders may be sent via email, SMS or similar means, to ensure their completion and alerts may be incorporated into the survey itself to detect when information is incomplete or the recorded responses are incorrect.15

Notwithstanding, prior to coming to a decision on the systematic recording of data using this method, we would have to explore the possible difficulties which may limit its viability, such as the barriers patients have in accessing new technologies, their inability to use them and the difficulties in correctly completing the questionnaires or the lack of assistance, particularly by family members with a higher level of competence in Internet usage.

One must take into account that the percentage of homes with Internet access in Spain is lower than the other EU countries (67% compared with 76%).14 Furthermore, predictably, older patients have greater difficulty using it and in completing questionnaires.

There are studies which argue that the cost of carrying out this type of questionnaire is lower than paper-based ones,18 although other studies support the fact that the cost of the questionnaires using this type of platform would depend on the sample size, larger samples being more profitable or beneficial.15 In our case, there was no evaluation of this type at the start of the study and therefore no calculation could be made.

It is probable that there will be a trend towards an increase in access to new technologies in Spanish homes, as has occurred up until now, thus increasing the capacity to respond to medical online surveys, when the population around us is more familiar with Internet usage and IT devices. The generations which currently use this type of technology will be our future study samples and probably fewer difficulties will be encountered for completing this type of survey.

The application used for completing the questionnaires was the website www.surveymonkey.com. Despite being a reliable and confidential site, probably the fact that it is external to the hospital leads patients to being somewhat reluctant to use it. Another telematic option to consider could be responding to surveys using a tablet which would collect the data in a computerised way. Easier and simpler-to-use tools or devices could possibly be designed which would help with completion of surveys but which at present we do not generally have at our disposition.

It is also worth mentioning that since survey completion in this study was low, the secondary objective regarding the creation of a valid and reliable telematic platform for obtaining HRQOL questionnaire measurements could focus on participants with better Internet access and a willingness to complete. We could also therefore address the possibility of having a mixed survey, whereby the patient chooses whether to complete the survey online or on paper.

Our study had several limitations; no relevant information was collected on patients’ social class or educational level, or the availability of assistance by a third party if required.

It is also of note that the opinion surveys used put forward 4 very subjective categories and without any definition of the criteria for each one of them. However, roughly speaking, they express the perception of patient difficulty.

To conclude, for the patients of our hospital scheduled for TKR surgery, Internet usage is not a viable strategy to ensure that quality of life data is obtained in a thorough and satisfactory manner.

Level of evidenceEvidence level V.

Ethical responsibilitiesProtection of human beings and animalsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this investigation.

Data confidentialityThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their centre of work on the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained the informed consent of patients and/or subjects referred to in this article. This document is in the possession of the corresponding author.

FinancingThe necessary resources for subscription and the web platform maintenance (300€) were financed by H.R., Fungibles S.L.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

We would like to thank the Statistics team from the Hospital de Sant Pau as well as all the nursing staff from the Orthopaedic and Traumatology Department for their participation in the undertaking of this study.

Please cite this article as: Besalduch-Balaguer M, Aguilera-Roig X, Urrútia-Cuchí G, Puntonet-Bruch A, Jordan-Sales M, González-Osuna A, et al. Nivel de cumplimiento vía telemática de cuestionarios relacionados con la calidad de vida en artroplastia total de rodilla. Rev Esp Cir Ortop Traumatol. 2015;59:254–259.