The lipofibrohamartoma is a rare entity of unknown origin that can affect any peripheral nerves, but mainly being found in the median nerve within the carpal tunnel. The lipofibrohamartoma is frequently associated with other conditions such as macrodactyly, the Proteus and Klippel–Trenaunay–Weber syndromes and multiple exostosis, among others.

Clinical casesTwo cases of lipofibrohamartoma in the carpal tunnel with associated median nerve palsy are described in the present article. They were treated by simple decompression of the median nerve by releasing the transverse carpal ligament and a palmaris longus tendon transfer to improve the thumb abduction (Camitz procedure). In one of the cases, (a previously multi-operated median nerve entrapment at the carpal tunnel), a posterior interosseous skin flap was employed to improve the quality of the soft tissues on the anterior side of the wrist.

DiscussionA review of the literature is also presented on lipofibrohamartoma of the median nerve, covering articles from 1964 to 2010. The literature suggests that the most recommended treatment to manage this condition is simple release of the carpal tunnel, which should be associated with a tendon transfer when a median nerve palsy is noticed.

El lipofibrohamartoma es una rara entidad nosológica de etiología desconocida que puede afectar a cualquier nervio periférico, localizándose de forma preeminente en el nervio mediano en el interior del túnel carpiano. El lipofibrohamartoma se asocia con frecuencia a otras alteraciones como la macrodactilia, los síndromes de Proteus y Klippel-Trenaunay, y la exóstosis múltiple, entre otras.

Casos clínicosLos autores han tratado en 20 años 4 lipofibrohamartomas del nervio mediano, dos de los cuales tenían parálisis mediana, motivo de este artículo. Estos pacientes se trataron con liberación simple del nervio mediano mediante apertura del ligamento anular del carpo y transposición tendinosa abductora con palmaris longus prolongado con la fascia palmar superficial (Técnica de Camitz). En uno de los casos, multioperado previamente, se realizó también un colgajo interóseo posterior para mejorar la calidad de las partes blandas de la cara anterior de la muñeca.

DiscusiónSe hace una revisión de la literatura sobre el lipofibrohamartoma del nervio mediano, los trabajos desde 1964 hasta 2010. La revisión de la literatura sugiere que el tratamiento más recomendado es la liberación simple del túnel carpiano y se recomienda asociar una transposición tendinosa si hay parálisis del nervio mediano.

Lipofibrohamartoma (LFH) is a rare pseudotumor which may affect any peripheral nerve. Its most frequent location is in the median nerve, inside the carpal tunnel. US literature attributes its first description to Mason, who presented the first 2 cases at a Congress of the American Society for Surgery of the Hand in 1953. Ulrich et al.1 attribute the first report of a median nerve LFH associated to macrodactyly to Koehler, who described it in an article published in Germany in 1888.

Multiple definitions can be employed to describe this pathology, but, in our opinion, LFH is the most suitable, since it is actually a hamartoma rather than a tumor as such. LFH is composed of variable percentages of fatty and fibrous tissue, interlinked between nerve fibers in a disorganized manner, thus compressing and displacing them and distorting intraneural anatomy, although without infiltrating nervous tissue directly. Its macroscopic appearance is a white mass of medium consistency, located and lost within a nervous pathway, sometimes making it impossible to identify the fascicular structure of the affected nerve. LFH causes the nerve to grow up to 3–6 times its normal diameter in the affected area. This is particularly noticeable when compared to healthy proximal and distal areas. The most peculiar observation is its association with other alterations, such as macrodactyly (a malformation characterized by hypertrophy of one or more fingers or toes), Proteus syndrome gigantism (abnormal growth of skin, bones, muscles, adipose tissue and blood and lymph vessels), Klippel–Trenaunay–Weber syndrome gigantism (multiple hemangiomas, varicose veins and hypertrophy of soft tissues, sometimes causing gigantism of the affected limb) and multiple exostosis, among others. The origin of these associations is not currently known, especially in the case of macrodactyly, which can affect over 30% of cases.2 It is significant that when LFH is associated with macrodactyly it is much more common in females than in males, thus suggesting a genetic origin.3

In connection with a literature review, treatment of LFH of the median and other nerves in general has been very controversial and even contradictory, until about 15–20 years ago, when it was better defined. The first cases reported in the literature advocated block resection of the tumor mass.2,3 Other cases opting for interfascicular resection noted the near impossibility of identifying the nerve fascicles, which led other authors to carry out complete excision, with or without reconstruction using nerve grafts. Given the irreversible sensorimotor neurological sequelae secondary to segmental resection of the median nerve, this option is currently obsolete.4 Nevertheless, some authors reported cases with successful results using aggressive surgery, thus adding to the confusion.5

The aim of the present work is to review the literature regarding LFH of the median nerve in the wrist, analyzing descriptions of clinical cases and indicating the characteristics of the disease, such as its most common clinical presentation, age at onset or diagnosis and recommended treatment. Between 1993 and 2010, one of the authors has treated 5 LFH in the wrist and hand, 4 of them affecting the median nerve in the wrist, 2 of which associated median nerve palsy and which are the subjects described in this article. The remaining 2 patients presented carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS) without median nerve palsy, which is precisely what makes the cases presented in this study unique. The patients evolved satisfactorily after simple carpal tunnel release, so they are not described in this article. The fifth case affected the ulnar nerve.

Case 1Case 1 was a 43-year-old, right-handed male, who reported suffering gigantism of the index and middle fingers (Fig. 1) at the time of birth, and who was operated at 2 years of age by amputation of the distal and middle phalanges of the middle finger. He attended consultation due to symptoms consistent with right CTS of 10 years evolution, for which he had previously been operated on 3 occasions, with no improvement, especially regarding night pain. He also reported a painful mass in the volar side of the wrist, radiating to the thumb, index and middle fingers upon contact, and which greatly limited his activities of daily living. Examination revealed an atrophy of the thenar eminence, with associated paralysis of the pollicis brevis, as well as highly painful Tinel sign in the anterior side of the wrist connected to the previously described mass. Wrist flexion testing (Phalen) and carpal compression testing (Durkan) were equally positive. A neurophysiological study confirmed advanced compressive neuropathy of the median nerve within the carpal tunnel.

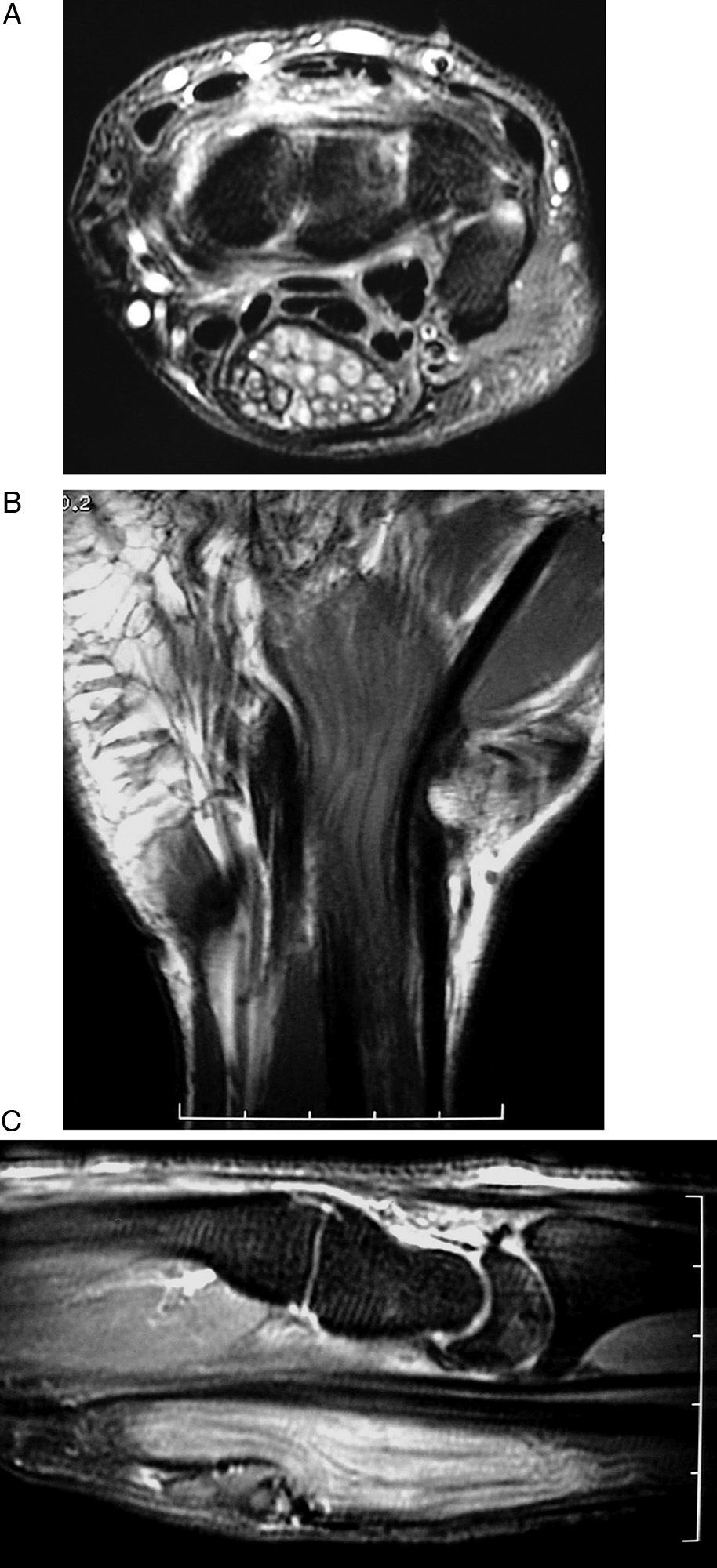

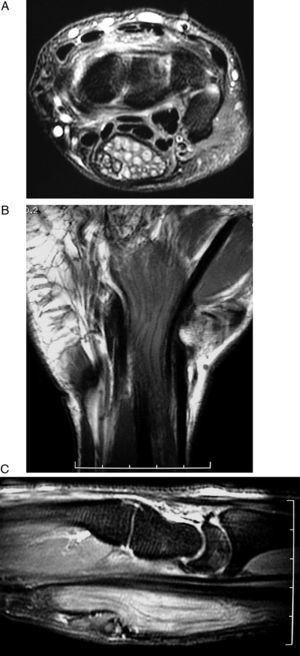

The radiological study showed a significant increase in size of the phalanges and metacarpals of the affected fingers. The magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) study revealed an image typical of median nerve LFH; a voluminous mass with a “wired” structure in its interior and an increase in resonance signal intensity, pathognomonic of this process (Fig. 2).

(A and B) Large, soft tissue mass, with a multiple “wired” aspect, corresponding to LFH of the median nerve. (C) The sagittal reconstruction shows stenosis of the nerve in the distal region of carpal tunnel and scarce coverage of soft tissues in the volar side of the wrist, which led to a posterior interosseous flap.

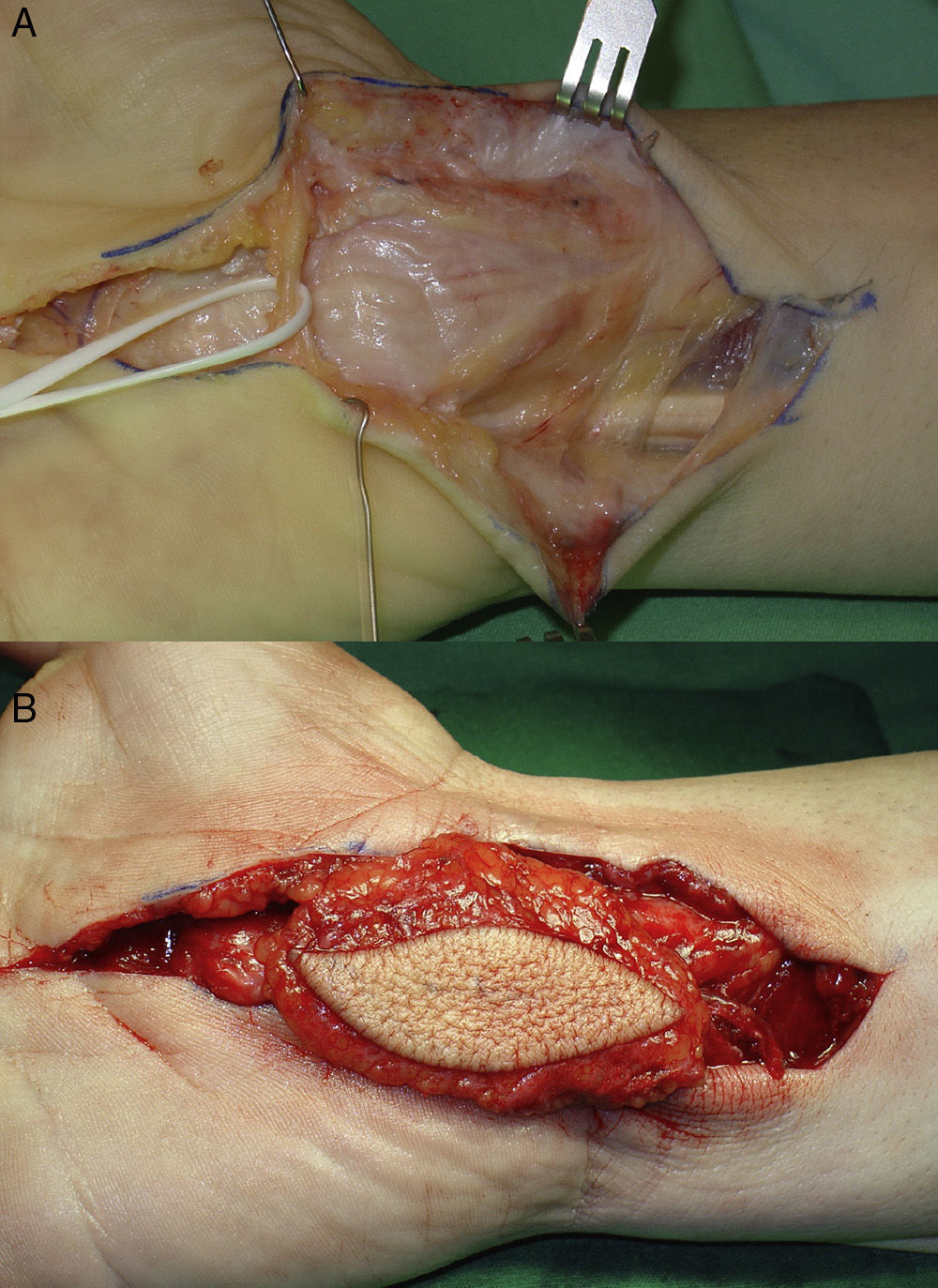

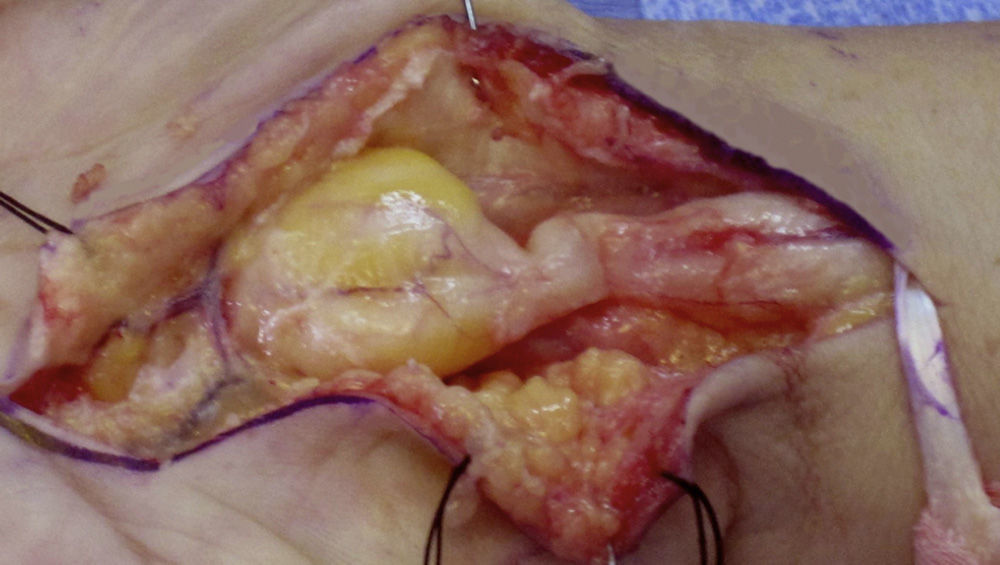

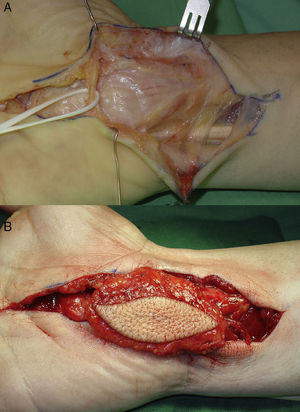

An extended carpal tunnel release was performed. Given the obvious diagnosis, biopsy was not performed. A posterior, fascio-fatty-cutaneous, interosseous flap was performed in order to improve the coverage of the volar side of the wrist. This provided protective padding, as well as a vascular contribution to the area in order to increase nerve regeneration (Fig. 3). The palmaris longus muscle, prolonged with the palmar fascia superficial to the insertion of the pollicis brevis, was transposed following the technique of Camitz6–9 in order to alleviate abductor paralysis.

(A) Intraoperative image showing the LFH of the median nerve, after release of the carpal tunnel. (B) The interosseous fascio-fatty-cutaneous flap was transposed to the anterior side of the mass of the LFH to improve vascularization of the median nerve and the quality of palmar skin.

Night pain disappeared in the immediate postoperative period; the pain upon contact on the volar side of the wrist became imperceptible at 3 months after surgery, once the scarring of the soft tissue of the flap became stabilized. Eight years after the intervention, the patient maintains an excellent abductor function of the thumb and the rest of the hand, with absence of pain and very scarce limitations for activities of daily living, except for those relating to rigidity of the index finger secondary to macrodactyly (Fig. 4). Given the long evolution of the neuropathy, thenar musculature has recovered partially, as well as sensitivity of the territory of the median nerve. Nevertheless, grip and pinch strength are normal compared to the contralateral hand (52 vs 55kg of grip strength and 19 vs 20kg of pinch strength). The patient is very satisfied with the result of the intervention.

Case 2The second case was a 56-year-old, right-handed female, who presented symptoms suggestive of right CTS of 10 years evolution (night pain, paresthesias in the territory of the median nerve and loss of strength). She also reported noticing progressive difficulty to separate the thumb from the palm and a progressive thinning of the thenar eminence, associated with decreased grip and pinch strength in the last 7 years. Examination found thenar muscle atrophy and paralysis of the pollicis brevis muscle. In addition, a significant increase in the volume of the palm, as well as the index and middle fingers and the volar side of the wrist were observed. Sensitivity of the territory of the median nerve was diminished, with positive CTS tests (Phalen, Durkan and Tinel tests). Electromyography suggested severe CTS. Moreover, she also presented De Quervain's tendinitis.

The radiological study indicated a slight increase in volume of the metacarpals and phalanges of the index and middle fingers. The MRI scan confirmed the diagnosis of suspected median nerve LFH, with similar findings to those described in case 1.

The patient was operated through an extended approach to the carpal tunnel, which was released in its entirety, confirming a very large pseudotumor corresponding to the median nerve, both proximally and distally to the carpal annular ligament, which caused compression on the anterior side of the mass.

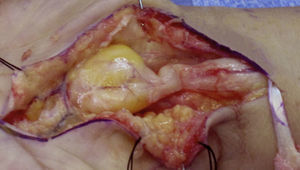

Biopsy of the pseudotumor mass was not performed, since the preoperative suspicion (macrodactyly, symptoms and conclusive imaging tests) pointed to LFH of the median nerve and the diagnosis was confirmed by the intraoperative pathognomonic appearance (Fig. 5). The palmaris longus tendon, prolonged with fibers of the superficial palmar fascia, was obtained in order to alleviate paralysis of the pollicis brevis. This was tunneled subcutaneously and inserted into the pollicis brevis tendon (Camitz technique).6–9 The first extensor compartment was released in the same surgical action.

Case 2: lipofibrohamartoma of the median nerve. A significant stenosis can be observed proximal to the pseudotumor, corresponding to the mark of the annular ligament of the carpus on the nerve. The difference in coloring and loss of surrounding adipose tissue due to extrinsic compression can also be observed. To the right of the image is the palmaris longus tendon, used to monitor the thumb.

Night pain disappeared in the immediate postoperative period and paresthesias improved gradually until their disappearance 1 year after surgery. Thumb anteposition and pinch motor function is excellent, with a normal tendon transposition function. At the time of the last examination, carried out 3 years after the intervention, the patient reported a normalization of activities using the right hand without any sensory deficit, as shown in Figure 6.

DiscussionLFH is a disorganized tissue characterized by an enlargement and hypertrophy of the epineurium and perineurium, interspersed with fibrous and fatty tissue deposits with normal histological properties. These abnormal accumulations deform and distort the nervous anatomy due to the infiltrative effect between and around fascicles and fascicular groups of the nerve.10 This infiltration causes the nerve structure to be unidentifiable and makes the nerve into a fusiform pseudotumoral mass with a volume 3–6 times that of the normal nerve. From a pathological point of view, LFH is a disorganized agglomeration of spindled and lobed fatty masses which increase the diameter and length of the affected nerve and intersperse into fibrous septa and nerve fascicles. The proximal and distal regions of the nerve are usually normal, but the affected segment can reach up to 10cm in length. A characteristic feature of LFH is that it does not adhere to surrounding tissues. Microscopically, the epineurium is enlarged and infiltrated by fibrofatty tissue, which separates and compresses the nerve fascicles.5 This infiltration causes atrophy of the neural elements, often followed by significant perineural fibrosis. Collagen deposition and loss of axons are indicators of these chronic changes. Some cases present perineural septa and formation of microfascicles.4

The etiology of LFH is unknown, although a congenital origin and an abnormal development of the retinaculum of the flexor tendons have been proposed. A traumatic origin or chronic inflammation of the nerve have also been suggested, although these do not seem feasible because in many cases the deformity is obvious at the time of birth.11 Amadio et al.3 postulated a common origin for LFH and macrodactyly, perhaps due to a genetic defect which could explain the concomitant development of both processes. Other authors, such as De Smet,12 have speculated that the hamartoma and associated nerve dysfunction could exert an influence on the development of macrodactyly, as both are often concurrent at birth, as documented in case 1. In this regard, it is worth noting that macrodactyly is usually located in the dependent territory of the nerve affected by hamartoma, as in the 2 cases reported and in the other 3 treated by one of the authors. The pathogenic correlation between the affected nerve and anatomical area is still unexplained, although it has been verified that when LFH affects the ulnar nerve macrodactyly affects the ring and little fingers, whereas when it affects the median nerve then the overdeveloped tissue is that of the remaining fingers. This hypergrowth affects the length and width of musculoskeletal tissues, generating grotesque deformities. In one of our cases, this led to partial amputation of the middle finger. Characteristically, this anomaly affects all digital structures.13

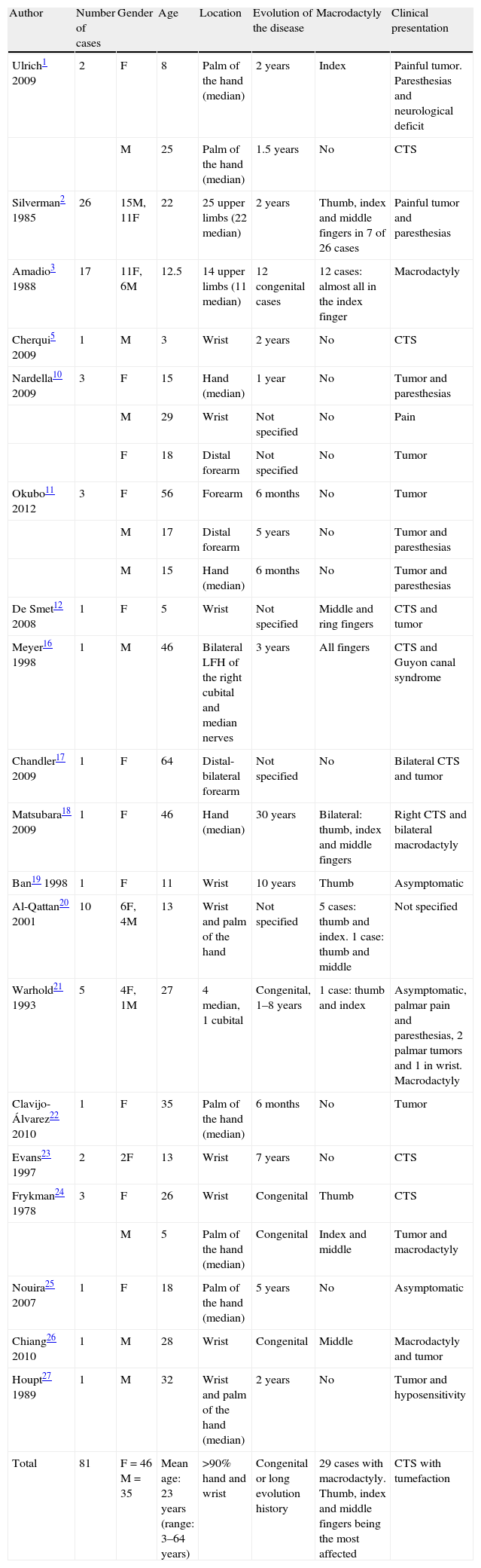

De Maeseneer et al.14 introduced the first classification of LFH, which divided it into 3 types: type I or isolated, type II, when it coexists with intramuscular fatty deposits, and type III, when it is associated with macrodactyly (macrodystrophia lipomatosa). This type corresponds to type I of the Dell classification of macrodactyly.15 After reviewing 56 articles, we found 132 cases of median nerve LFH, although not all have been referenced in this article (Table 1), with type I being the most frequent (67% of cases). The disease affects females and males equally (71 females and 61 males), with a mean age of onset of 21 years, and being most frequently located on the right side; with bilateral cases being very rare.16,17 Involvement of the median nerve occurs most frequently in the wrist and palm, with its appearance in the digital territories being rare. It is associated to macrodactyly in one third of cases. In such cases, the female/male ratio is of 2–1. The 4 cases of LFH of the median nerve which the authors have had the chance to treat were all associated with macrodactyly, and were 2 males and 2 females. LFH is also associated with other pathological processes, such as Klippel–Trenaunay–Weber syndrome,18 Proteus syndrome, vascular malformations19 and bone and fat tumors.20

Relevant data of the literature review conducted.

| Author | Number of cases | Gender | Age | Location | Evolution of the disease | Macrodactyly | Clinical presentation |

| Ulrich1 2009 | 2 | F | 8 | Palm of the hand (median) | 2 years | Index | Painful tumor. Paresthesias and neurological deficit |

| M | 25 | Palm of the hand (median) | 1.5 years | No | CTS | ||

| Silverman2 1985 | 26 | 15M, 11F | 22 | 25 upper limbs (22 median) | 2 years | Thumb, index and middle fingers in 7 of 26 cases | Painful tumor and paresthesias |

| Amadio3 1988 | 17 | 11F, 6M | 12.5 | 14 upper limbs (11 median) | 12 congenital cases | 12 cases: almost all in the index finger | Macrodactyly |

| Cherqui5 2009 | 1 | M | 3 | Wrist | 2 years | No | CTS |

| Nardella10 2009 | 3 | F | 15 | Hand (median) | 1 year | No | Tumor and paresthesias |

| M | 29 | Wrist | Not specified | No | Pain | ||

| F | 18 | Distal forearm | Not specified | No | Tumor | ||

| Okubo11 2012 | 3 | F | 56 | Forearm | 6 months | No | Tumor |

| M | 17 | Distal forearm | 5 years | No | Tumor and paresthesias | ||

| M | 15 | Hand (median) | 6 months | No | Tumor and paresthesias | ||

| De Smet12 2008 | 1 | F | 5 | Wrist | Not specified | Middle and ring fingers | CTS and tumor |

| Meyer16 1998 | 1 | M | 46 | Bilateral LFH of the right cubital and median nerves | 3 years | All fingers | CTS and Guyon canal syndrome |

| Chandler17 2009 | 1 | F | 64 | Distal-bilateral forearm | Not specified | No | Bilateral CTS and tumor |

| Matsubara18 2009 | 1 | F | 46 | Hand (median) | 30 years | Bilateral: thumb, index and middle fingers | Right CTS and bilateral macrodactyly |

| Ban19 1998 | 1 | F | 11 | Wrist | 10 years | Thumb | Asymptomatic |

| Al-Qattan20 2001 | 10 | 6F, 4M | 13 | Wrist and palm of the hand | Not specified | 5 cases: thumb and index. 1 case: thumb and middle | Not specified |

| Warhold21 1993 | 5 | 4F, 1M | 27 | 4 median, 1 cubital | Congenital, 1–8 years | 1 case: thumb and index | Asymptomatic, palmar pain and paresthesias, 2 palmar tumors and 1 in wrist. Macrodactyly |

| Clavijo-Álvarez22 2010 | 1 | F | 35 | Palm of the hand (median) | 6 months | No | Tumor |

| Evans23 1997 | 2 | 2F | 13 | Wrist | 7 years | No | CTS |

| Frykman24 1978 | 3 | F | 26 | Wrist | Congenital | Thumb | CTS |

| M | 5 | Palm of the hand (median) | Congenital | Index and middle | Tumor and macrodactyly | ||

| Nouira25 2007 | 1 | F | 18 | Palm of the hand (median) | 5 years | No | Asymptomatic |

| Chiang26 2010 | 1 | M | 28 | Wrist | Congenital | Middle | Macrodactyly and tumor |

| Houpt27 1989 | 1 | M | 32 | Wrist and palm of the hand (median) | 2 years | No | Tumor and hyposensitivity |

| Total | 81 | F=46 M=35 | Mean age: 23 years (range: 3–64 years) | >90% hand and wrist | Congenital or long evolution history | 29 cases with macrodactyly. Thumb, index and middle fingers being the most affected | CTS with tumefaction |

| Author | Affected side | Associated disease | Preoperative paralysis | Treatment | Recurrence of symptoms | Monitoring | Postoperative neurological deficits |

| Ulrich1 2009 | R | No | No | CTR and partial excision | No | 8 years | No |

| L | No | No | CTR and partial excision | No | 6 years | No | |

| Silverman2 1985 | Not specified | No | No | CTR and total or partial excision | 3 of 18 cases | Not specified | In 20% of excisions |

| Amadio3 1988 | 7 L, 10 R | Klippel–Trenaunay–Weber syndrome | No | 11 total or partial excisions, 6 amputations, 4 CTR, 3 neurolysis, 8 volume reductions | 2 cases | 8 years | Hypoesthesia |

| Cherqui5 2009 | L | No | No | CTR+total excision+sural nerve graft | No | 18 months | No |

| Nardella10 2009 | R | No | No | No treatment | No | 6 months | No |

| R | No | No | CTR | No | Not specified | No | |

| R | No | No | No treatment | No | Not specified | No | |

| Okubo11 2012 | R | No | No | Excision and biopsy | No | 6 months | No |

| R | No | No | CTR and biopsy | No | 6 months | No | |

| R | No | No | CTR and biopsy | No | 4 years | No | |

| De Smet12 2008 | R | No | No | CTR and thinning of digital nerves | No | 6 years | No |

| Meyer16 1998 | Bilateral | No | No | CTR+epineurolysis of the median and cubital nerves | No | Not specified | No |

| Chandler17 2009 | Bilateral | No | No | CTR in the left side+biopsy | No | 9 months | Paresthesias |

| Matsubara18 2009 | R | Klippel–Trenaunay–Weber syndrome | No | CTR | No | 20 months | No |

| Ban19 1998 | R | Vascular malformation: red marks on neck, thorax and arm | No | Excision of digital nerves and thumb volume reduction. No tendon transposition. | No | Not specified | No |

| Al-Qattan20 2001 | Not specified | 2 adipose and 2 bone tumors | No | 2 CTR, 1 CTR+excision of cutaneous palmar nerve, 2 isolated volumetric reductions and 5 associated to CTR | 1 case | Not specified | No |

| Warhold21 1993 | 3 R, 2 l | No | No | 2 CTR, 2 excisions without graft and 1 with graft | No | 3.5 years | 1 case of sensitivity deficit |

| Clavijo-Álvarez22 2010 | R | No | No | CTR+total excision+sural nerve graft | Yes | 3 years | No |

| Evans23 1997 | Not specified | No | No | Volume reduction+CTR+total excision+opponensplasty with indicis proprius extensor | No | 3 years | CTS |

| Frykman24 1978 | R | No | No | CTR, median total excision and unspecified opponensplasty | Yes | 2.5 years | Hypoesthesia |

| L | No | No | CTR, volume reduction of affected fingers and excision of digital nerves | No | 3 months | No | |

| Nouira25 2007 | L | No | No | No treatment | No | Not specified | No |

| Chiang26 2010 | L | Neurofibroma of the median nerve in forearm (“skip lesion”) | No | Not specified | No | No | No |

| Houpt27 1989 | L | No | No | CTR and interfascicular neurolysis | No | 2 years | Thumb opposition deficit |

| Total | 26 R, 15 L, 2 bilateral | Some cases associated to Klippel–Trenaunay–Weber syndrome or bony tissue or soft tissue tumors | No | Most cases were treated by CTR+partial excisional biopsy, and volumetric finger reduction. Two palliative tendinous transpositions by complete resection of the median | 10% | Mean follow-up: 3 years (range: 3 months–8 years) | Sensory in 50% of excisions and motor in 15% of excisions |

CTR: carpal tunnel release; CTS: carpal tunnel syndrome; F: female; L: left; LFH: lipofibrohamartoma; M: male; R: right.

The prevalence of LFH is very low and most publications refer to isolated cases. One of the authors (JGP) has treated just 5 cases after 20 years of exclusive dedication to hand pathologies at a reference center. The literature review shows 3 articles with a high number of cases which are worth commenting. The first is from Al-Qattan20 who, being a reference for infantile hand pathology in Saudi Arabia, a country with 27 million inhabitants, treated 10 cases of LFH in a period of 7 years. Amadio et al.3 found their 17 cases by reviewing the files of the Mayo Clinic between 1935 and 1985. Finally, Silverman and Enzinger,2 from the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology in Washington, the largest referral center in the US for musculoskeletal pathology, found their 26 cases over a period of 43 years.

In the literature review we found that the most common clinical presentation was CTS associated with a mass in the volar side of the wrist or proximal side of the palm. Moreover, subjects may present associated esthetic problems if the mass is large and sensory and/or motors deficits if compression is prolonged, as in the cases presented. This pathology is rarely asymptomatic. When associated to macrodactyly, the most commonly affected fingers are the index and middle fingers. This fact is linked with the innervation of the median, which is by far the most commonly affected nerve.

The diagnosis of LFH is obtained clinically and through magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), as its images are pathognomonic and due to fibrofatty tissue being interposed between and around nerve fibers, without directly infiltrating them. Axial sections present a multiple “wired” aspect, and coronal and sagittal sections present a “spaghetti” aspect. MRI is also very useful for the differential diagnosis with intraneural lipoma, which has a capsule separating it.

According to the literature, the most controversial aspect is treatment. In our review, almost all patients were operated by release of the carpal tunnel and a biopsy was obtained in many cases, except in 40 cases in which full or partial excisions were performed, and in 4 which were treated conservatively (Table 1). Approximately half of those receiving treatment suffered severe motor-sensory deficits, although in some cases the defects were repaired with sural nerve grafts.5,21,22 Logically, the best results were obtained in children. Tendon transposition was only performed in 2 cases, when thumb function was affected by median nerve palsy, and both presented good results.23,24 In cases where the symptoms were scarce, the literature reviewed suggested an absence of therapy.6,25,26

In our opinion, treatment is contraindicated by the irreversible sequelae it produces and by the difficult return of nerve function, not only motor but especially sensory, since the motor function can be alleviated by tendon transpositions, but the sensory damage is irreparable. This sequela is directly proportional to the defect created by resection and the age of the patient.4 Neurolysis is equally damaging to nerve vascularization, leading to interfascicular fibrosis.27 This is due to the fact that nerve fascicles are impossible to locate, identify and release from the fatty tissue surrounding them, as they are lost within the fatty mass. An attempt to release the nerve tissue in this adverse situation only worsens the prognosis. Furthermore, the diagnosis is evident from the symptoms and the imaging study, and is corroborated by inspection of the affected nerve, which also contraindicates excisional biopsy, with simple release of the median nerve in the carpal tunnel28 being the treatment of choice, along with motorization of the thumb in case of established median nerve paralysis.6–9

Median nerve LFH in the wrist should only be treated by simple release in the carpal tunnel at an early stage, in order to prevent the progressive establishment of paralysis of the thumb. In fact, the existence of paralysis makes this problem different from non-paralytic CTS, because simple release without added transposition is an insufficient treatment. In cases with paralysis, simple release will not enable nerve recovery, and palliative surgery by palmaris longus tendon transposition must be performed. Sensitivity will be recovered if the evolution is not very long, although night pain disappears almost immediately.

Level of evidenceLevel of evidence iv.

Ethical responsibilitiesProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that this investigation did not require experiments on humans or animals.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their workplace on the publication of patient data and that all patients included in the study received sufficient information and gave their written informed consent to participate in the study.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare having obtained written informed consent from patients and/or subjects referred to in the work. This document is held by the corresponding author.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

The authors wish to express their gratitude to Dr. M. Dolores Gimeno García-Andrade, from the Hand Surgery Unit at Hospital Universitario San Carlos, in Madrid, for her invaluable collaboration in one of the cases presented in this work.

Please cite this article as: Biazzo A, González del Pino J. Parálisis del nervio mediano secundaria a lipofibrohamartoma en el túnel carpiano. Rev Esp Cir Ortop Traumatol. 2013;57:286–95.