The aim of this study is to measure the DIP joint angle of the little finger and presence of degenerative changes in the DIP joint in Basque hand-pelota players and compare it with the general Spanish population.

Material and methodsCross-sectional study. We studied both hands of 40 male Basque pelota players (pelotaris) and 20 male controls. The assessment protocol consisted of a questionnaire, physical examination and bilateral plain radiographs. Distal interphalangeal (DIP) joint angle was measured on plain radiographs in both hands.

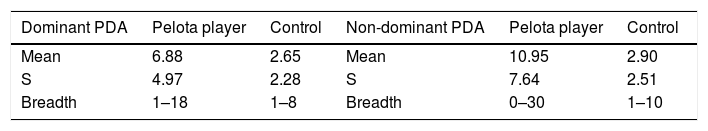

ResultsThe average DIP joint angle of the little finger in the control group was 2.6° in the dominant hand and 2.9° in the other hand. In the pelota players group we obtained a DIP angle of 6.8° in the dominant hand and 10.9° in the non-dominant hand. The DIP angle was significantly higher in the non-dominant hand (p=.002) in the pelota player group. Non-significant differences were obtained between both hands in the control group (p=.572). Significant differences were obtained in both player and control groups in the dominant hand (p=.001) and in the non-dominant hand (p=.001). Pelota players have a higher DIP angle in the little fingers than the control group. No differences were found in the pelota player group according to their position on the court (p=.742 forward, p=.747 defender) or sport level (p=.345 amateur, p=.346 professional).

DiscussionBasque hand-pelota produces post-traumatic acquired clinodactyly of the little finger. The non-dominant hand has a higher DIP joint angle. Clinodactyly poses no functional problems.

Cuantificar la desviación angular de la articulación interfalángica distal (IFD) del 5.° dedo y la presencia de cambios degenerativos en IFD en jugadores de pelota y compararlos con una población española.

Material y métodosEstudio de casos y controles de una población de 40 pelotaris manomanistas federados y de un grupo control formado por 20 varones no practicantes de pelota. Se calcularon el ángulo IFD y la presencia de cambios degenerativos en la articulación.

ResultadosEl ángulo IFD medio del 5.° dedo en el grupo control fue de 2,6° en la mano dominante y de 2,9° en mano no dominante. Grupo de pelotaris: ángulo IFD de 6,8° en mano dominante y 10,9° en la no dominante. El ángulo IFD fue significativamente mayor en la mano no dominante (p=0,002) en el grupo de pelotaris. No se encontraron diferencias significativas entre ambas manos en el grupo control (p=0,572). Se hallaron diferencias estadísticamente significativas tanto para la mano dominante (p=0,001) como para la no dominante (p=0,001) al comparar grupo control con pelotaris. Los pelotaris tienen un ángulo IFD superior a los controles en ambas manos. No se encontraron diferencias estadísticamente significativas en grupo pelotari según la posición en la cancha (p=0,742 delantero, p=0,747 zaguero) ni por categorías (p=0,345 aficionado, p=0,346 profesional).

DiscusiónLa práctica de pelota a mano se asocia a la presencia de una clinodactilia postraumática de la falange distal del 5.° dedo. La mano no dominante presenta unos ángulos mayores en IFD. La presencia de clinodactilia no genera limitación funcional.

Basque pelota is a sports activity mainly practised in the north of Spain, the south of France and the Americas.1–3 Hand pelota is a professional activity with a high social and economic impact in the regions where it is practised. The weight of the ball used ranges between 90g and 106g, depending on the different sport levels and federations, reaching speeds of over 100km/h. The ball is directly hit with the hand covered by protective cushioning, called “tacos” (studs), which are attached by means of tape. The impact area on the hand is variable, depending on the position of the pelota player on the court (forward or defender), and the different types of strike (volleying, hitting up high, propelling), with the area on the 2nd, 3rd, and 4th metacarpophalangeal joints those which presented with the highest rate of injury.1–3

Post-traumatic clinodactyly of the little finger consists in the angular deviation of the distal phalanx of the 5th finger of both hands and in the presence of degenerative changes in the distal interphalangeal joint (DIP).4 This commonly presents in pelota players, and has been previously described in other studies, although its intensity has not been quantified nor correlated with population values of people who do not practice this sport.5

The aim of this study was clinical assessment and quantification of the DIP joint angle deviation of the little finger in Basque hand-pelota players in radiographic testing and to compare it with a representative sample of the Spanish population.

Material and methodsCase and control study of a population of 40 federated Basque hand-pelota players and a control group formed by 20 men who did not practice hand pelota.

The inclusion criteria of the cases were: aged between 18 and 40. Regular and continuous practice of hand pelota, being federated in a club as a non-professional or professional player and taking part in pelota federation competitions. The patients in both groups signed an informed consent form for participation in the study. Exclusion criteria were considered to be the presence of an active or tumoral infectious disease and a history of previous surgery. For the control groups, patients who played hand pelota recreationally or occasionally were excluded.

The main clinical variables for analysis were: age, weight, height, body mass index (BMI), dominant hand, position in the court (forward or defender), DIP measurement of 5th finger in a radiographic and goniometric study, plus the presence of osteoarthritic changes in DIP. Clinodactyly was defined as the radial deviation of the distal phalanx of the 5th finger, with an angulation equal to or higher than that of the 4th finger.

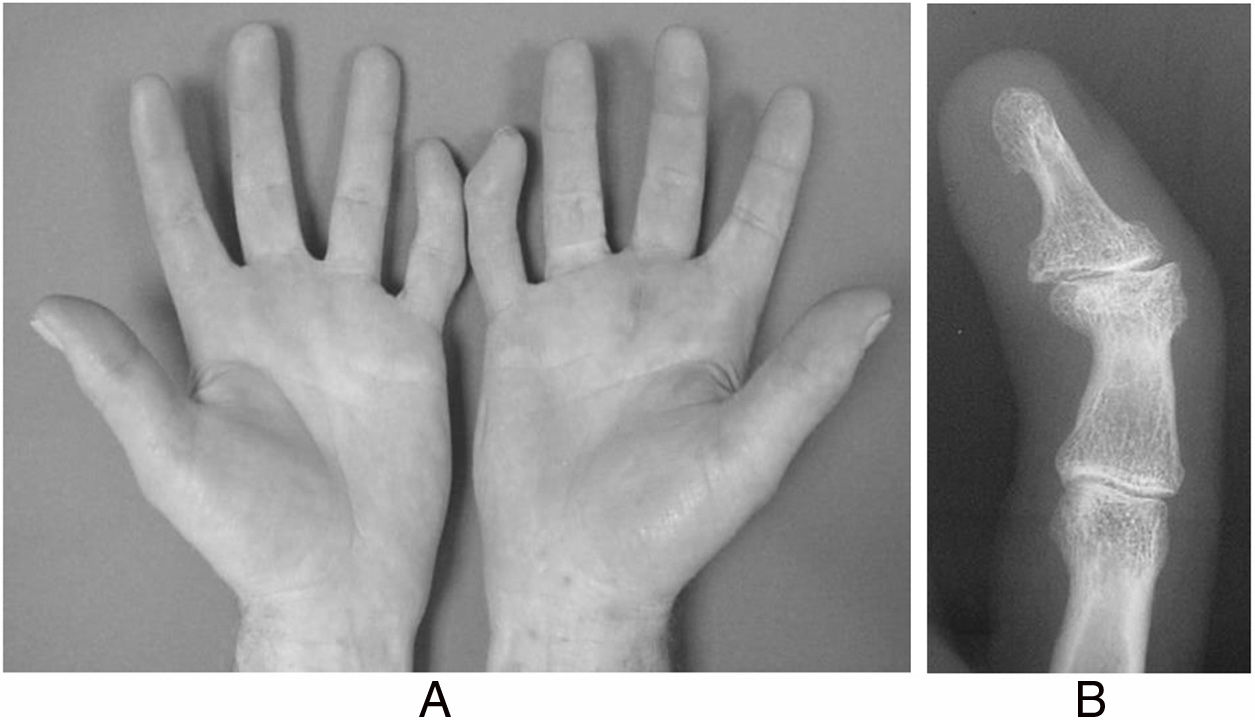

Protocol consisted in the study of both hands in all cases (pelota players and control group) through physical examination (Fig. 1A) and radiographic assessment of hand in anteroposterior and oblique positions (Fig. 1B). For radiographic assessment a longitudinal line from the axis of the mid phalanx was traced and the angle obtained between both lines was calculated using the reader of the angles from the software system incorporated into the radiographic visual display (Fig. 2). Data collection of case and control groups was performed in a standardised and homogeneous manner for both groups. Clinical and radiographic assessments were made by the corresponding author.

Acquired post-traumatic clinodactyly of both little fingers of the professional hand pelota player. (A) Image of the professional pelota player: bilateral clinodactyly and hyperkeratosis of the palm. (B) X-rays of the 5th finger of the hand in anteroposterior projection where post-traumatic clinodactyly may be observed.

The Excel 2008 programme was used for data collection and table design. Statistical analysis of data was performed using the IBM SPSS statistics 15.0 software for health sciences (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA), where the database was created. For statistical analyses quantitative variables were expressed as mean±standard deviation and qualitative data as absolute frequencies and percentages. For variable contrast the Student's T-test was used for independent variables and correlated for quantitative variables and the Chi-square test was used for the qualitative variables. Statistical significance was established as 95% (p<.05).

All participants were informed of the study protocol and voluntarily accepted it. This protocol was presented and approved by the hospital ethics committee.

ResultsIn the group of hand-pelota players (n=40), 18 players were forwards and 22 were defenders, with 23 plays being amateurs and 17 professionals. No significant differences were found between the number of forwards and defenders in keeping with the sports level (p=.75).

The dominant hand was the right in 85% of the pelota players and 90% of the control group members.

The mean age was 23.6 years (17–39) in the pelota player group and 26.6 (21–39) in the control group. BMI in the control group was 25.1 and 24.6 in the control group. Weight in the pelota player group was 81.6kg and 81.7kg in the control group. There were no significant differences between the pelota player group and the control group regarding BMI (p=.422), height (p=.281) and weight (p=.977), but they did exist with regards to age when the study took place (p=.037). The magnitude of difference in age (3 years) was not a bias in the variables to be studied. There were no significant differences between the professional and amateur subgroup regarding BMI (p=.161) but there were for age at the time of the study (p=.016), height (p=.032) and weight (p=.023). As expected, the physical build of the professional pelota players (height and weight) was greater than that of the amateurs. No significant differences were found between the forward and defender subgroup regarding age at the time of study (p=.296) or BMI (p=.082) but they were found regarding height (p=.006) and weight (p=.003). The physical build of the defenders is greater than that of the forwards. The defenders have greater power and resistance and the forwards are more agile, faster and have greater reflexes.

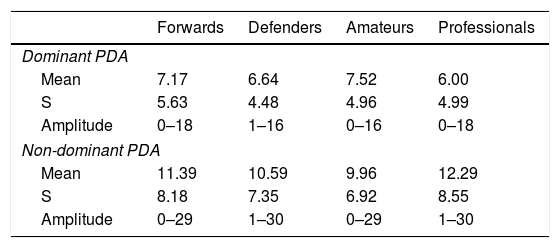

The mean DIP angle of the 5th finger in the control group was 2.6° in the dominant hand and 2.9 in the non-dominant hand. In the pelota player group we found a DIP angle of 6.8° in the dominant hand and of 10.9° in the non-dominant hand (Table 1). The DIP angle was significantly higher in the non-dominant hand (p=.002) than in the pelota player group. No statistically significant differences were found between both hands in the control group (p=.572). Statistically significant differences were found both in the dominant hand (p=.001) and the non-dominant hand (p=.001) when comparing the control group with that of the pelota players. The pelota players have a higher DIP angle to the control groups in both hands (Table 2). No statistically significant differences were found between the pelota player group according to the position on the court (p=.742 forward, p=.747 defender) or sport level (p=.345 amateur p=.346 professional).

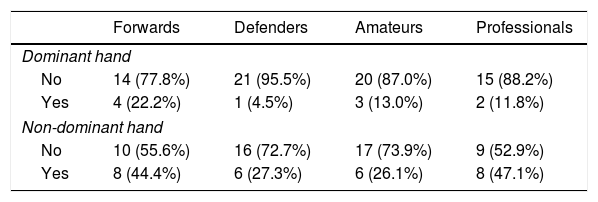

Degenerative changes were observed in the DIP joint of the little finger of the non-dominant hand in 14 pelota players (35%) and in 5 pelota players (12.5%) of the domain hand. There were statistically significant differences when both hands were compared (p=.012) (Table 3). There were no statistically significant differences in the presence of degenerative osteoarthritic phenomena in the DIP joint of the 5th finger of the dominant hand and the non-dominant hand according to the position in the field (p=.155 dominant, p=.327 non-dominant) or sport level (p=.646 dominant, p=.149 non-dominant).

Osteoarthritis in DIP joint of the little finger according to position played and sport level.

| Forwards | Defenders | Amateurs | Professionals | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dominant hand | ||||

| No | 14 (77.8%) | 21 (95.5%) | 20 (87.0%) | 15 (88.2%) |

| Yes | 4 (22.2%) | 1 (4.5%) | 3 (13.0%) | 2 (11.8%) |

| Non-dominant hand | ||||

| No | 10 (55.6%) | 16 (72.7%) | 17 (73.9%) | 9 (52.9%) |

| Yes | 8 (44.4%) | 6 (27.3%) | 6 (26.1%) | 8 (47.1%) |

Clinodactyly of the little finger and the degenerative changes in DIP joint did not cause pain nor required any treatment at the time of the study.

DiscussionThe radial deviation of the 5th finger (acquired post-traumatic clinodactyly) in Basque hand pelota players has been described by other authors.1–5 This consists in angular deviation of the distal phalanx of the 5th finger of both hands and in the presence of degenerative changes in the DIP joint.6–8

As shown from the results of our study, the appearance of the deformity is clearly related to the practice of a sport and does not appear in the non-hand-pelota playing population which was used as the control group. Basque hand pelota also leads to early degenerative changes in sportspeople, which is not present in the general population at such as early age.9–12

In general, the pelota players do not complain about this problem and rarely seek medical attention for it.13–15 No functional limitation ensues in the sportsperson and some of the older ones are even proud of it as a sign (or stigmata) of having played pelota in their youth, since in some regions it is considered a sport with massive connotations.

Several theories exist regarding the aetiology of this deformity. Some authors report that the deviation could be caused by a traumatic epiphysiolysis with partial epiphysiodesis (physary bridge) in the distal phalanx but no study has been able to demonstrate this.16–18 In our personal experience as physicians who increasingly treat pelota players, we have not found any epiphysolysis or partial epiphysiodesis of the distal phalyange in radiographies of pelota players with open physes and some of them have developed the deformity in adult age after physary closure.

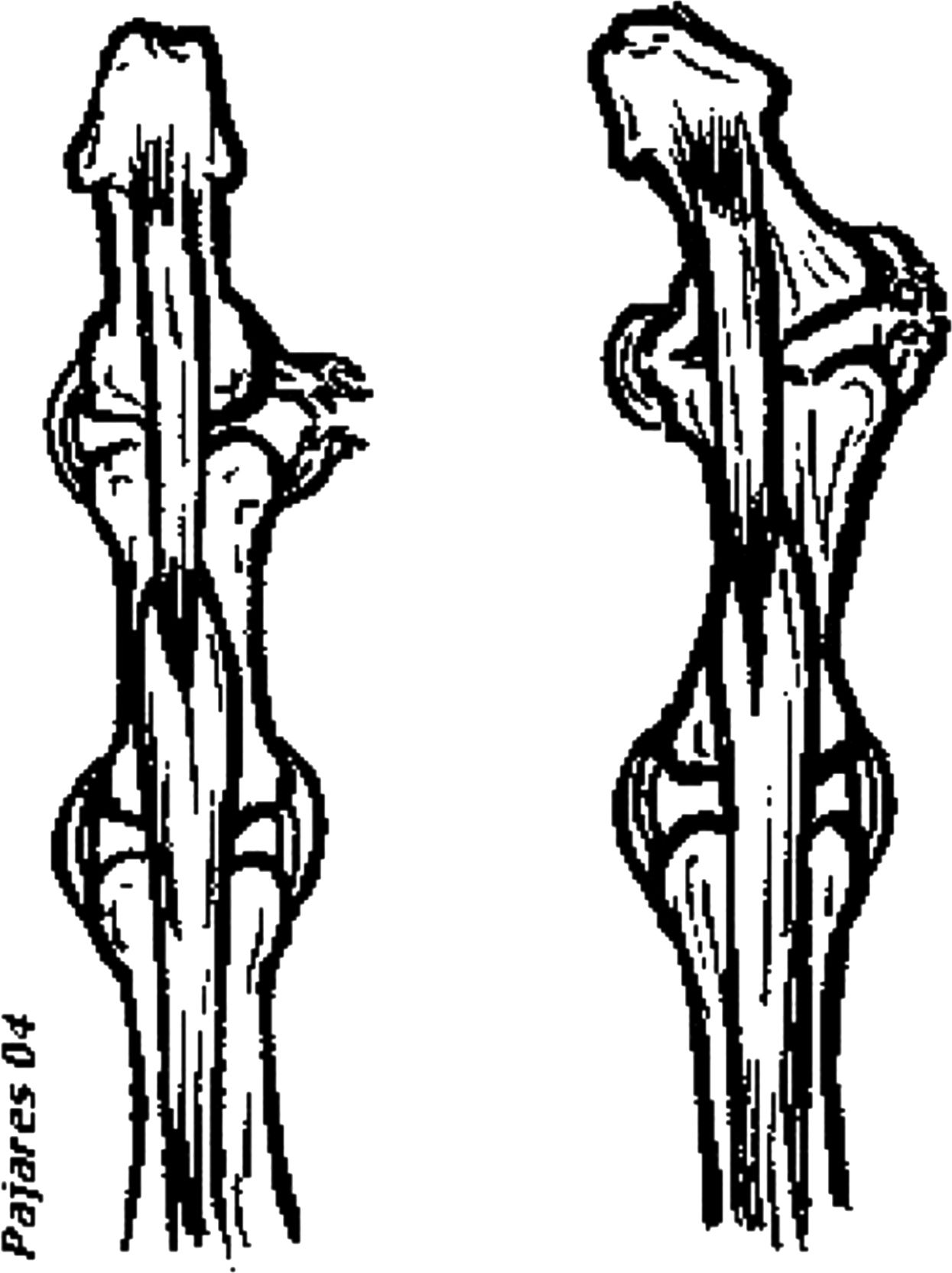

We believe that the deformity happens because of recurrent sprains of the ulnar collateral ligament of the DIP joint, secondary to repetitive trauma against the ball or the left wall of the court. These sprains are usually not treated, not immobilised and the pelota player continues playing and the DIP joint develops a lateral instability, which may be demonstrated with examination in some sportspeople during our regular medical practice on the pelota courts. The tractor effect of insertion of the deep flexor tendon of the fingers in the distal phalange acts as a bowstring developing the deformity (Fig. 3). In many X-rays calcification of the ulnar collateral ligament may be observed and a narrowing of the DIP joint of the little finger (Fig. 4). In acute cases there is pain and instability in that region.

(A) X-ray of the 5th finger of DIP of male pelota player aged 24 years with a dominant left hand with image of calcification of the ulnar collateral ligament. (B) X-ray of the 5th finger of DIP of male pelota player aged 26 years with a dominant right hand with degenerative changes in DIP.

It is more common in the left hand because most of the most difficult hits are near the left wall and it is easier to injure the hand, either against the wall or the ball.

There are no differences in prevalence due to the position on the court (forward or defender) or the sports sport level (amateur/professional).

ConclusionsThe continuous practice of hand pelota is associated with the presence of a post-traumatic clinodactyly of the distal phalanx of the 5th finger. This deviation does not appear in individuals who do not play pelota.

This deviation does not lead to limitations in practicing sports or carrying out daily life activities.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Our thanks to Dr. Samuel Pajares Cabanillas, from the Clínica Universidad de Navarra in Madrid, for the illustrations provided.

Also to the Department of Health of the Government of Navarre for the grant received for conducting this study.

The grant for Research projects in Health Sciences Department of health of the Government of Navarre (Regional Order 1036/1999. Case 22/1999).

Please cite this article as: Barriga-Martín A, Romero-Muñoz LM, Aquerreta-Beola D, Amillo-Garayoa S. Clinodactilia postraumática del meñique en el pelotari manista. Rev Esp Cir Ortop Traumatol. 2020;64:160–166.