There are few studies on Fracture Liaison Service (FLS) that evaluate older patients after a hip fracture (HF) through comprehensive geriatric assessment. We aim to determine these patients’ characteristics, outcomes, and prescribed treatments.

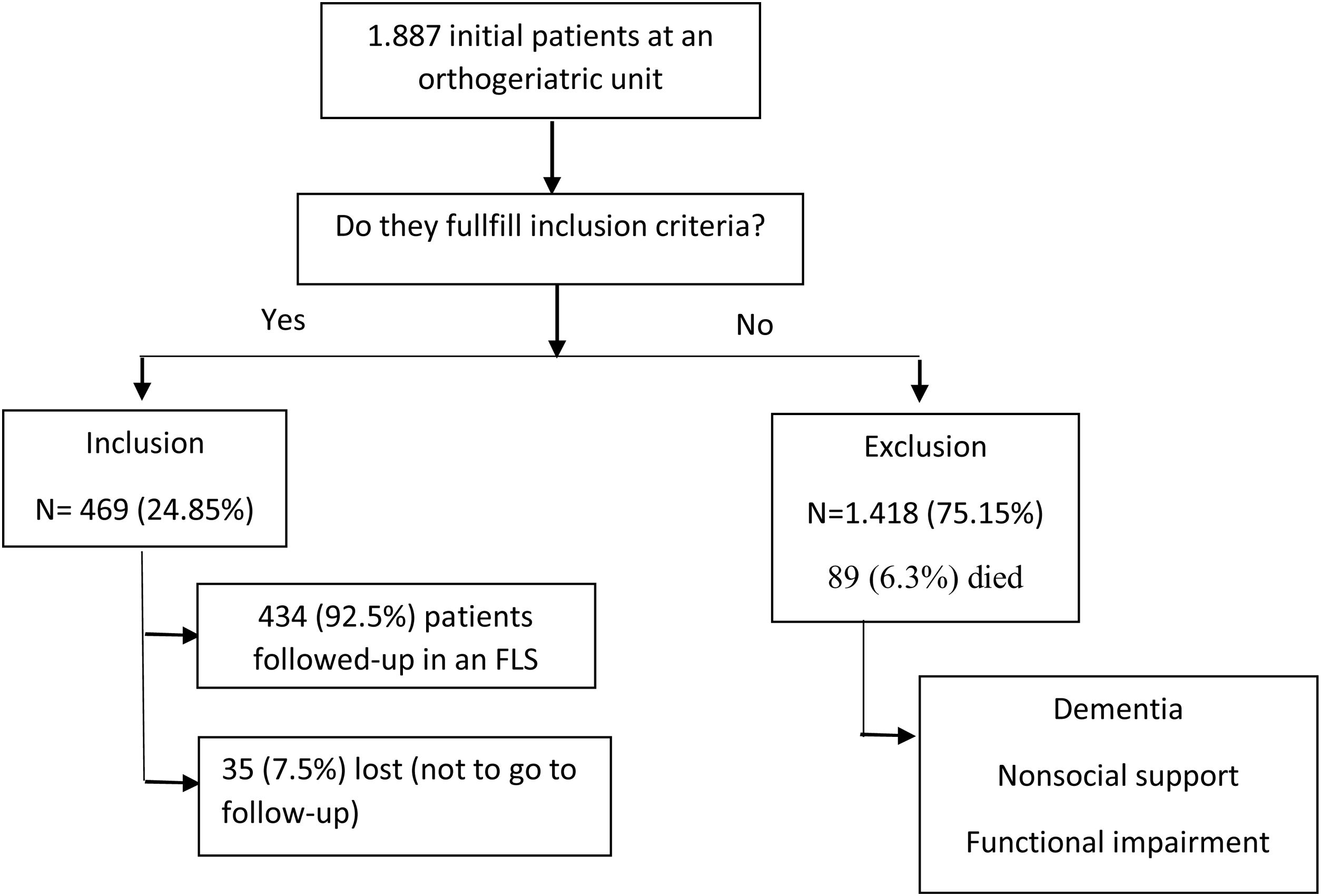

MethodsA retrospective observational study of a cohort of patients older than 65 years admitted with HFs to an orthogeriatric unit between February 25th (2013) and December 16th (2016). After hospitalization, those patients with a good baseline social, functional, and cognitive situation were referred to the FLS. A comprehensive geriatric assessment and treatment adjustment were conducted. A comparison between FLS patients and HF patients non-referred was made.

ResultsFrom 1887 patients admitted to the orthogeriatric unit, 469 (24.85%) were referred to the FLS. Of those, 328 were women (75.6%) and 337 (77.6%) lived in the community. The FLS patients had a better functional status (96.8% of the patients with independent gait versus 64.8%) than non-FLS patients (p<0.001). After 3 months in the FLS, 356 (82%) patients had independent gait and had improved their analytical values. Antiosteoporotic treatment was prescribed to 322 patients (74%), vitamin D supplements to 397 (91.5%), calcium to 321 (74%), and physical exercise to 421 (97%).

ConclusionsPatients referred to an FLS were younger, with a better functional and cognitive situation. At hospital discharge, they frequently presented gait impairment and laboratory abnormalities (anemia, hypoproteinemia, vitamin D deficiency) that presented good recovery due to the patient's previous baseline. These patients benefit from comprehensive treatment (pharmacological and non-pharmacological).

Hay pocos estudios sobre las unidades de coordinación de fracturas (Fracture Liaison Services [FLS]) que evalúen a pacientes mayores tras una fractura de cadera (FC) a través de una valoración geriátrica integral. Nuestro objetivo es determinar las características de estos pacientes, los resultados y los tratamientos prescritos.

MétodosEstudio observacional retrospectivo de una cohorte de mayores de 65años ingresados tras fractura de cadera (FC) entre el 25 de febrero de 2013 y el 31 de diciembre de 2016 en una unidad de ortogeriatría. Tras el alta hospitalaria, los pacientes con buen soporte social y buena situación funcional y cognitiva fueron citados en la FLS. Se realizó una evaluación geriátrica integral y un ajuste del tratamiento. Dichos pacientes se compararon con pacientes con fractura de cadera no derivados a esta unidad.

ResultadosUn total de 1.887 pacientes ingresaron en la unidad de ortogeriatría, y 469 (24,85%) fueron derivados a la FLS. De ellos, 328 fueron mujeres (75,6%) y 337 (77,6%) vivían en el domicilio. Los atendidos en la FLS tuvieron mejor funcionalidad (96,8% de pacientes con deambulación independiente versus 64,8%) que los no incluidos (p<0,001). A los 3meses en la FLS, 356 (82%) pacientes presentaban deambulación independiente y habían mejorado sus valores analíticos. Se prescribieron antiosteoporóticos a 332 pacientes (74%), suplementos de vitaminaD a 397 (91,5%), calcio a 321 (74%) y ejercicio físico a 421 (97%).

ConclusionesLos pacientes atendidos en una FLS fueron más jóvenes, con mejor situación funcional y cognitiva. Al alta hospitalaria, frecuentemente presentaron inestabilidad de la marcha y alteraciones analíticas (anemia, hipoproteinemia, déficit de vitamina D) que tuvieron buena evolución dado el estado previo del paciente. Estos pacientes se benefician de un tratamiento integral (farmacológico y no farmacológico).

With population aging and the significant increase in osteoporosis, today's society is facing an increase in frailty-related fractures. It is estimated that in the year 2050 there will be about 6 million hip fractures,1 thus, making this a worldwide problem that we cannot ignore.

The incidence of hip fracture (HF) is growing in European countries due to the aging of the population and has become a public health problem in most European countries such as the United Kingdom and Spain.2 Within frailty-related fractures, HFs are the ones with the worst health outcomes due to their association with an increase in morbidity and disability in basic activities of daily living, cognitive impairment, and other factors including an increase in 1-year mortality rates.3 Most studies have focused only on bone metabolism treatments4 and have not considered other aspects of assisting older patients who present more complications such as functional and cognitive impairment, pain, malnutrition, and comorbidities. These patients, therefore, present different clinical characteristics.

Fracture Liaison Services (FLS) emerged as a multidisciplinary management model to reduce the risk of a second fracture in those patients who have presented a frailty-related fracture.5 Their main function is to identify patients who have experienced fractures and comprehensively assess all elements that increase the risk of another fracture to reduce it and, if needed, initiate antiosteoporotic treatment.6

In the reviewed literature on FLS, most studies are population-based and include a wide range of patients with different types of fractures, with means their mean ages are much lower than those found in patients with HFs, and few studies have included older patients with HFs.4,7

In general, the risk evaluation of new fractures includes a study of the risk factors, previous drugs, and compliance with antiosteoporotic drug treatment. With older adults, however, non-pharmacological interventions (comprehensive assessment with multi-component exercise, assessing the risk of falls, preventing polypharmacy, healthy diet, smoking cessation, avoiding alcohol) must be the first approach to fracture prevention.8

In order to do this, there are various models, the most effective of which not only identifies patients who have experienced fractures, but also studies the risk of new fractures, indicates treatment, and coordinates the follow-up.9 The benefits of FLS shown by studies include the increased diagnosis and treatment of osteoporosis, the reduced risk of new fractures, the greater efficiency in health care, and the reduction in mortality.10 Each FLS conducts different activities, but few detailed explanations of their functions have been published.11

The approaches that have been published so far regarding FLS interventions are highly limited. Thus, this is the first study to assess HF geriatric patients comprehensively through an FLS, including functional, and cognitive descriptions and the pharmacological changes made throughout the follow-up.

The objective of this study is to describe the clinical, functional, and blood test profile of patients referred to an FLS after a HF using a comprehensive geriatric assessment with a multicomponent intervention and to describe their 3-month progression and the specific treatments they have taken.

Materials and methodsStudy designThis is a retrospective observational study of a patient cohort referred to an FLS for HF.

Participants and settingsEvery patient older than 65 years of age who was admitted with a HF to the acute orthogeriatric unit at Hospital Universitario La Paz, Madrid (Spain) between the 25th of February 2013 and the 16th of December 2016 was assessed. 1887 patients were admitted to the orthogeriatric unit during this period. The unit's patient management protocol has been previously described,12,13 known as FONDA for Function, Osteoporosis, Nutrition, Pain, and Anemia. We describe the aim of the protocol in the baseline and admission assessment.

Basement and admission assessmentDuring admission to the orthogeriatric unit, the patients were treated by the orthopedic surgeon, geriatrician, and orthogeriatric nurse. In addition to the usual orthogeriatric care, the patients were managed with a standardized protocol of comprehensive treatment, which included: (1) prescription of physical exercise right after admission to improve their functional status; (2) instructions to treat vitamin D deficiency if it was detected through oral supplements; (3) nutritional oral high-protein supplementation for hospitalized patients at risk of malnutrition (defined as hypoproteinaemia [(<6.5mg/dL], hypoalbuminemia [<3.5mg/dL], low body mass index [BMI<22kg/m2] or low oral intake); (4) scheduled pain medication consisting of paracetamol with metamizole and, if needed, tramadol; and (5) red blood cell concentrate transfusion if the hemoglobin level was <9g/dL or <10g/dL in patients with diseases affecting vital organs and intravenous iron infusion in case of iron-deficiency anemia or the risk of having the condition.

A comprehensive geriatric evaluation was conducted at admission and discharge, and the cases selected for follow-up were evaluated 3 months after the fracture.

Data was collected by the orthogeriatric nurse during the first 72h after hospital admission, on discharge day, and during the medical visit. The clinical baseline variables were age, sex, place of residence, current diseases, number and type of prescribed drugs, American Society of Anesthesiologists Physical Status Classification, and abbreviated Charlson Index. In this study, we considered patients could walk independently when the Functional Ambulation Category score was ≥4.14 Activities of daily life were assessed using the Barthel index,15 and the previous mental state was assessed using the Red Cross Mental Scale and Pfeiffer's Short Portable Mental Status Questionnaire (SPMSQ)16 at admission and discharge, with cognitive impairment considered as an SPMSQ score>2. Hemoglobin, vitamin D, calcium, total serum protein, and albumin levels were recorded. Pain severity was assessed using the verbal rating scale of Morrison et al.,17 which classifies pain from 0 (no pain) to 5 (unbearable pain) while at absolute rest and while weight-bearing at discharge. Information was collected on whether antiosteoporotic medication, vitamin D, and calcium were prescribed before hospital admission and at discharge.

Assessment at FLSThose patients who were considered able to attend and who would benefit from follow-up in the FLS were selected for the appointment. Of 1887 patients admitted, 469 (24.85%) were referred to the FLS.

The eligibility criteria for an appointment to the FLS were (1) admission due to a frailty-related HF in the orthogeriatric unit, (2) a functional situation and social support system that would make it possible for the patient to attend the appointment and (3) sufficiently unimpaired mental health that would make following all recommendations a feasible possibility.

All the patients received treatment and exercise indications following the hospital protocol at discharge whether they were included in the FLS or not.

The selected patients were re-evaluated at the FLS medical visit 3 months after the fracture by the orthogeriatric nurse and geriatrician, during which a comprehensive geriatric assessment, detection of frailty, blood test, pain evaluation, and diet review were conducted. Whether the patients were taking antiosteoporotic drugs and whether they were performing the physical exercise program was recorded.

During the FLS examination, some of the clinical variables were obtained and blood samples were obtained. Furthermore, physical frailty was assessed using the Short Physical Performance Battery,18 while handgrip strength was measured using a Jamar® hydraulic dynamometer. The established parameters were as follows: anemia when the hemoglobin level was <13g/dL in men and <12g/dL in women; hypoproteinaemia when the total serum protein level was <6.5mg/dL; and hypoalbuminemia when the albumin level was <3.5mg/dL. Low grip strength was considered <23kg for men and <13kg for women. These cut-off points were obtained from the reference values of a previous study of a population-based cohort that assesses the target population of the same hospital's area (the Peñagrande Cohort Study).19 Bone health medication and physical exercise prescriptions were re-evaluated and re-recorded. Physical exercises consisted of a previously described multicomponent program12 that included physical strength, balance, and flexibility exercises.

Statistical analysisWe performed a descriptive analysis of the variables at baseline, on admission, and at follow-up. The study was designed to recruit patients for 3 years. The final sample was made up of 1887 patients, of whom 469 attended the consultation. This sample size allows, with 80% power, to find differences between groups of 5 points in the Barthel index and 10% in the proportion of patients with independent walking, cognitive impairment, and ASA or SPMSQ>2, as well as adjusting a model of logistic regression with the analyzed variables. The quantitative variables are presented as mean values and standard deviations, while the qualitative variables are presented as absolute numbers and relative frequencies. We calculated the statistical significance of each variable's associations using a paired samples t-test, chi-square test, Fisher's exact test the analysis, we considered 0.05 as the indication of statistical significance. The data analysis was performed using SAS software v9.4 (Copyright © 2013 SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC, USA).

Ethical considerationsThis research project was approved by the research ethics committee of the La Paz Hospital where the study was conducted (protocol number PI-3261).

ResultsOf the 1852 patients admitted to the orthogeriatric unit during the research period, 469 met the inclusion criteria for referral to the FLS and were therefore given an appointment. Ultimately, 434 visited the clinic. The mean waiting time from admission to the appointment was 108 (SD 32) days (Fig. 1).

Patients’ characteristicsTable 1 shows the characteristics of the patients admitted to the orthogeriatric unit based on whether they were referred to the FLS or not. Geriatric patients referred to the FLS after a frailty-related HF were of similar age, Barthel Index, and cognitive status, and both were mostly living in the community. However, more patients in the FLS group (96.8% vs 64.8%) had independent gait without statistical differences.

Characteristics of patients with hip fractures, classified according to whether or not they were referred to the Fracture Liaison Service (n=1887).

| Non-referred patients | Patients referred to the FLS | OR (95% CI) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 1418 | 469 (24.85%) | ||

| Baseline | ||||

| Age, years | 86.0±7.6 | 84.4±5.8 | 1.02 (0.99, 1.05) | <0.001a |

| Women, n (%) | 1068 (75.3%) | 328 (75.6%) | 1.45 (0.93, 2.26) | 0.99b |

| Independent gait | 919 (64.8%) | 420 (96.8%) | 1.03 (0.33, 3.24) | <0.001a |

| Barthel index | 71.2±26.4 | 93.5±10.0 | 1.05 (1.03, 1.08) | <0.001a |

| Cognitive impairment | 237 (16.7%) | 3 (0.7%) | 0.46 (0.20, 1.05) | <0.001b |

| Living in their own home | 1.049 (74.0%) | 337 (77.6%) | 8.14 (1.96, 33.9) | <0.121b |

| Hospital admission | ||||

| ASA Scale>II | 1106 (78.0%) | 234 (54.0%) | 0.49 (0.33, 0.73) | <0.001a |

| Pfeiffer's SPMSQ>2 | 413 (29.1%) | 11 (2.3%) | 0.23 (0.15, 0.35) | <0.001b |

| At discharge | ||||

| Independent gait | 31 (2.2%) | 25 (5.8%) | 0.99 (0.22, 4.40) | <0.001c |

| Barthel index | 30.4±17.6 | 47.7±13.6 | 1.01 (0.99, 1.03) | <0.001a |

| Pfeiffer's SPMSQ>2 | 429 (30.3%) | 13 (3%) | 0.41 (0.23, 0.73) | <0.001b |

| Discharge destination | <0.001b | |||

| Own home | 305 (21.6%) | 167 (38.5%) | Ref | |

| Nursing home | 516 (36.5%) | 37 (8.5%) | 0.24 (0.10, 0.58) | |

| Rehabilitation unit | 478 (33.8%) | 228 (52.5%) | 0.98 (0.56, 1.74) | |

| Deceased | 89 (6.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | – | |

| Other | 30 (2%) | 2 (0.5%) | – | |

Regarding the ASA and Pfeiffer scale results, both parameters seem to show better results in patients referred to the FLS. In the case of the ASA scale, 78% of patients not referred had a score over II (p<0.001), while only 53.9% of the patients in the FLS group achieved this score. In the case of the Pfeiffer test, 29.1% committed > 2 errors in the not referred group, whereas 2.3% of the patients referred reached this score (p<0.001).

At discharge, significant differences were found concerning independent gait and Pfeiffer scale results in patients referred to the FLS.

When analyzing discharge destination, we observed significant differences in every parameter analyzed, with a higher presence of both home-bound discharges and referrals to rehabilitation units in patients included in the FLS group versus a higher rate of institutionalization and death in patients not included (p<0.001).

When carrying out the multivariate analysis applying three models, we found that gait independence ceases to be a significant parameter, giving way to cognitive and social (defined as living in their home) situations being the most relevant factors.

Furthermore, in regards to the institutionalization and referrals to rehabilitation units, the differences found in the univariate analysis were maintained.

MortalityThe mean hospital mortality ranges between 4 and 5%, being 6.3% in our study in those not included in the FLS and 0 in those who met the inclusion criteria.

Evolution of patients in the followed-up (Table 2)

Evolution of patients with hip fractures followed-up in a Fracture Liaison Service (n=434).

| Hospitalization | At dischargea | FLS consultationa | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Independent gait | 420 (96.8%) | 13 (2.9%) | 356 (82%) |

| Walking aids | |||

| None | 385 (88.7%) | 5 (1.2%) | 86 (19.8%) |

| 1 walking stick | 42 (9.7%) | 4 (0.9%) | 220 (50.7%) |

| 2 walking sticks | 3 (0.7%) | 24 (5.5%) | 29 (6.7%) |

| Walking frame | 4 (0.9%) | 401 (92.4%) | 99 (22.8%) |

| Barthel index | 93.5±10 | 47.75±13.65 | 83.7±18.2 |

| Pfeiffer's SPMSQ>3 | 87 (19.6%) | 83 (19.1%) | 86 (19.8%) |

| Pain at rest | |||

| Mild (0–1) | – | 370 (85.2%) | 428 (98.6%) |

| Moderate (2–3) | – | 55 (12.7%) | 6 (1.4%) |

| Severe (4–5) | – | 9 (2.1%) | 0 (0%) |

| Pain when weight bearing | |||

| None/mild (0–1) | – | 101 (23.3%) | 393 (90.6%) |

| Moderate (2–3) | – | 258 (59.4%) | 41 (9.4%) |

| Severe (4–5) | – | 75 (17.3%) | 0 (0%) |

| Anemia | |||

| Men<13g/dL | – | 101 (95.3%) | 34 (32%) |

| Women<12g/dL | – | 289 (88.1%) | 45 (13.7%) |

| Hypoproteinaemia<6.5mg/dL | – | 303 (69.9%) | 91 (20.96%) |

| Hypoalbuminemia<3.5mg/dL | – | 337 (78.6%) | 48 (11.05%) |

| Vitamin D<30ng/mL | – | 404 (93.1%) | 108 (25%) |

HF=hip fracture; FLS=Fracture Liaison Service; SPPB=Short Physical Performance Battery.

At 3 months, all clinical, functional, and analytical parameters show significant improvement when referred to the FLS, except for cognition quantified by the Pfeiffer test.

Pharmaceutical managementTable 3 shows the treatments prescribed at the different moments during the patients’ evolution. The prescription rate rose from 15.4% at baseline to 91.5% at the FLS for vitamin D, from 15.7% to 74.2% for antiosteoporotic drugs, and from 10.8% to 74% for calcium supplements. Oral nutritional supplements were required in almost all cases during the hospital stay and for 60% of the patients at discharge. Physical exercises were prescribed to all patients during the hospital stay and at discharge and to 97% of the patients at the FLS consultation.

Prescribed treatments for patients with hip fractures followed-up in a Fracture Liaison Service.

| Baseline | Admission | Discharge | Visit to the FLS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vitamin D | 67 (15.4%) | 340 (78.3%) | 419 (96.5%) | 397 (91.5%) |

| Calcium | 47 (10.8%) | – | 368 (84.4%) | 321 (74%) |

| Antiosteoporotic drugs | 68 (15.7%) | – | 118 (27.2%) | 322 (74.2%) |

| Oral nutritional supplements | – | 402 (92.6%) | 258 (59.4%) | 65 (15%) |

| Multimodal exercise prescription | 430 (99.1%) | 430 (99.1%) | 421 (97.0%) |

Our results show that, after suffering a HF, patients referred to a FLS were in their eighties, complex, and more likely to be community-dwelling. There were clear differences regarding age and functionality status between the patients who were referred to the FLS and those who were not due to the inclusion criteria. In addition, all the clinical, functional, and analytical parameters analyzed in the patients referred to the FLS showed evolutionary improvement of the sample selected for the FLS. Furthermore, if we compare the Spanish Hip Fracture Registry and other international registries,20 we can see that most of the patients in these international registries lived in the community (around 70%) and a small percentage had cognitive impairment (less than 30%), which aligns with the results obtained in our project.

A mortality of 2% during hospitalization was observed, which, if compared with the Spanish Hip Fracture Registry, is within the range, as shown. As shown in some articles and according to the characteristics of the patient's, a worse prognosis may be seen.21Other articles also focus on recovery after 3 or 6 months, showing that the patients do not recover to the previous situation.22

On discharge, between 15 and 30% of patients returned home. We have seen an increase in this percentage in our study in the patients referred to the FLS, going up to 38.5%. Usually, 32% of patients are transferred to functional recovery units in Spain, while in countries such as Ireland, Australia, or Germany this percentage increases up to 50%, closer to the results provided in this study.

Our patients were among the oldest FLS patients described in the literature. The mean age was 85.8 years, older than that of previous studies where the mean age ranged from 71 to 82.5 years.23,24 This fact is important because as a patient's age increases, so does their complexity and comorbidity. As far as we know, there have only been a few studies with a similarly aged population. A study by Gosch et al.,23 which included patients with a mean age of 82.5 years who attended a geriatric fracture center, focused specifically on osteoporosis treatment. Only 15% of their patients had a previous HF.

On discharge, 226 (61.42%) patients had been prescribed oral bisphosphonates; however, 65% of the 160 patients who were followed up after 12 months had stopped taking the oral bisphosphonates. In the Spanish Hip Fracture Registry,20 the rate of bisphosphonate prescription on discharge for patients with a mean age of 86.7 years after a HF in 54 Spanish hospitals was higher than for our patients (37% vs. 27.2%) but we have found it was much lower at followed-up (41% vs. 74.2%).

The study's antiosteoporotic treatment prescription rate was similar to ours (74.2% in our study vs. 68.8% in the study by Gosch et al.,23 for antiresorptive therapy, 91.5% vs. 95.6% for vitamin D supplementation, and 74% vs. 80.2% for calcium supplementation respectively). In other Spanish studies, Naranjo et al.,24 describe an FLS in which 75% of the patients were taking bisphosphonates at 6 months and Gamboa et al.,25 analyzed also data from 85-year-old patients discharged for HF.

Most studies on the FLS experience of patients with HF have shown that the FLS prioritizes actions on the bone metabolism and have described the results along this line but do not include other aspects e.g., the increase in detection of osteoporosis,26 the establishment of osteoprotective treatments,24,26 the reduction in posterior fracture, and the increase in healthcare efficiency.2,27 The results in terms of secondary fracture prevention are important, but these patients also need to be addressed and managed comprehensively. Our study not only took antiosteoporotic treatment into account but also considered the patients’ comprehensive geriatric assessment. Several studies have implemented a geriatric HF care program and education on fall prevention,28 while others have included a comorbidity evaluation26 and even a functional assessment.25 However, they do not describe a comprehensive geriatric assessment, the patients’ clinical details, or the need for other treatments, which are needed to recover the patients’ general condition and function.

After the hospitalization process with the follow-up in the FLS, we applied European guidelines for antiosteoporotic treatment and an individualized multicomponent approach to improving their recovery.

The period between the start of the study and the follow-up also influences the results. Currently, the recommended time to start drug treatment is when patients experience a fracture and are hospitalized. Pape and Bischoff Ferrari30 proposed that treatment for patients with HFs should begin upon discharge from the orthogeriatric unit itself rather than waiting for a medical visit a few months after the fracture. Thus, even geriatric patients who are unable to attend FLS consultations will benefit from secondary fracture prevention.

The differing patterns and models of FLS make comparisons between them very difficult. There is diversity in the literature in terms of the follow-up time after a HF, with several FLS studies including a follow-up of 6 to 12 months,28 while other studies established follow-up after 3 months, as in our case.29 Each FLS has also its own protocol. However, there is more agreement in the literature regarding the best patient candidates for follow-up in any FLS. These patients would be the ones who experience a frailty-related fracture, who live in the community, and have good functionality and no cognitive impairment.23,26–29

This study analyzed a large number of HF cases included in 4 years, representing the study population reflecting a particularly complex, vulnerable, and older population compared to previous studies in a tertiary referral hospital with a target population of 520,000 residents and a large number of variables are taken into account, including variables regarding physical function, cognitive evaluation, and blood test results.

However, there are some limitations that we have to take into account. It is a retrospective observational study. Also, the patient selection bias is due to the inclusion criteria. Only those patients with a good baseline social, functional, and cognitive situation were referred to the FLS, to make attending the appointment more possible and following the medical recommendations more likely.

ConclusionIn conclusion, this study assesses HF geriatric patients referred to an FLS and describe the clinical, functional, and blood test profile that identify the rates and evolution of geriatric syndromes. Our results show that these situations are very common in such patients and should be necessary a comprehensive non-pharmacological and pharmacological treatment to improve the secondary prevention of fractures. This recommendation should be included in future guidelines for those patients older than 65 years who experience a HF and could benefit from an FLS follow-up due to the major complexity of the condition in order to reduce the risk of a second fracture.

FundingResearch Foundation of La Paz University Hospital and by financial support from Nestle Health Science to the Research Foundation of La Paz University Hospital in 2012 for the establishment of the FONDA Cohort. (FONDA Cohort Study, PI-1334 Project). Nicolás Martínez Velilla received funding from “la Caixa” Foundation.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

We thank Nestle Health Science to the Research Foundation of La Paz University Hospital and Navarrabiomed. Also, all the authors for their support during the implementation of the study.