This study analyzes whether experienced and new Internet users react differently to online discounts and gifts. The results obtained in a multi-group SEM analysis show that experienced users are more influenced by online sales promotions and have a greater purchase intention than new users. However, although both groups of Internet users show a predisposition to purchase the promoted service, experts form an opinion about the Web advertisements when they see an online discount and they change their attitude toward the brand when they see an online gift, while no significant differences are observed in the novice users’ response to promotional incentives. The findings of this research help us understand better the way Internet users process different types of promotional incentives communicated through banners, and to what extent the experience in the use of Internet affects that process.

Esta investigación analiza si los expertos y los noveles en el uso de Internet reaccionan de igual o diferente forma ante los descuentos y los regalos on-line. A través de un análisis SEM multigrupos se obtiene que los expertos se ven más influidos por las promociones de ventas on-line, generando una mayor intención de compra que los noveles. Sin embargo, aunque ambos grupos de internautas presentan una predisposición a comprar el servicio promocionado, a los expertos los descuentos les sirven más para generar una opinión acerca del anuncio Web y los regalos on-line para cambiar su actitud hacia la marca, mientras que no se observan diferencias significativas en la respuesta de los noveles en función del incentivo promocional. Los hallazgos de esta investigación ayudan a comprender mejor la forma en que los internautas procesan diferentes tipos de incentivos promocionales comunicados a través de banners y en qué medida la experiencia de uso Web afecta a dicho procesamiento.

Among the online marketing communication tools with the highest growth in recent years, it is worth mentioning the sales promotion (Valassis.es, 2012). Sales promotion has been considered by some marketing managers in the industry as the most valuable communication tool for their business (ANA, 2012). Concerning the consumer's perspective, the “Trends in online Shopping” study determines that 30% of Internet users make their purchases online driven by special offers seen on the Internet, while only 18% of them are driven by online advertising (Nielsen, 2008). It is estimated that 32.5% of European users have used Groupon coupons at least once, while in 2012, 95.5 million Europeans used online incentives in 2012 (eMarketer.com, 2012). In Spain, 7.4 million Internet users have used discounts on portals such as Groupon and Groupalia, 25% of which are active seekers of online coupons (Nielsen, 2012). All these figures show the current importance of online sales promotion in the corporate marketing strategies and explain the effort directed by academia toward understanding how this communication instrument works in the online environment. Therefore, it is worth considering the following issues: What variables affect or precede consumer behavior in the face of an online sales promotion? Are all types of sales promotions on the Internet equally efficient? Do online sales promotions affect all Internet users in the same way? Another question that arises in connection with the previous ones is whether the proliferation of different online promotional incentives will solely and exclusively affect the consumer behavior variables or they will have an impact on its antecedents, such as attitude toward the brand and, therefore, on the brand equity.

The traditional (offline) means have proven that one of the key moderating variables of the impact of a sales promotion is precisely the type of incentive offered in it (monetary vs. non-monetary) (Buil, De Chernatony, & Martinez, 2011; Büttner, Florack, & Göritz, 2015; Mittal & Sethi, 2011; Reid, Thompson, Mavondo, & Brunsø, 2015). The different ways of integrating the promotional information related to every type of incentive will possibly affect the global processing of the incentive itself and, therefore, its impact on the consumer behavior (Montaner, De Chernatony, & Buil, 2011).

Literature has also highlighted that user's prior experience with the Internet is one of the moderating variables with the greatest impact on the user's final response to corporate marketing actions. This variable affects the decision making process and the information processing (Hoffman & Novak, 1996; Flavián-Blanco, Gurrea-Sarasa, & Orús-Sanclemente, 2012; San José-Cabezudo, Gutirrez-Arranz, &Gutirrez-Cillán, 2007). According to the general studies about experience with the technology, this variable is a strong predictor for both attitude and behavior regarding technology (Thompson, Higgins, & Howell, 1994). Several studies have proven that expert and novice use the information systems differently (King & Xia, 2007), determining the nature of their searches, their frequency of use and their online purchase behavior.

We can therefore affirm that prior experience with the Internet influences consumers’ online behavior and their preferences and assessments of online brands and products (Thorbjornsen & Supphellen, 2004). This paper seeks to contribute to the existing knowledge about the functioning of online sales promotion, focusing on the banner format as a transmitter of promotional incentives, for being one of the most common promotion methods used by companies on the Internet (eMarketer.com, 2013; IABEurope, 2013; IABSpain, 2013). In spite of the recent developments in alternative advertising formats, the traditional banner keeps being one of the most usual formats even today. The report published in September 2012 by eMarketer about the evolution of online advertising spending in the USA highlighted that banners or display ads were the most widespread format after the search engine ads. In 2012, it accounted for an overall advertising spending of $8.68 billion, being expected to reach $11.29 billion in 2016 (eMarketer.com, 2012).

The situation is very similar in Europe, as shown by some studies carried out by the IABEurope (2013). In Spain, which is the geographic region of this research, advertising spending on display ads accounted for 25.56% of the overall online advertising spending in 2012, according to IABSpain (2013).

In short, the main purpose of this study is to analyze how online discounts and gifts communicated through banners affect the formation of attitudes toward online purchases and the purchase intention, as well as to find out to what extent users’ level of Web experience moderates such relationship.

An interesting theoretical contribution of this paper is the integration of the theories of information processing (Petty & Cacioppo, 1981, 1986), sales promotion processing (Inman, McAlister, & Hoyer, 1990) and online information processing (Hershberger, 2003), within a single theoretical framework including the main developments introduced by each of these theories to date. This way, the theories are simplified in a single theoretical framework gathering their synergies and including the key differences of each of them. This paper represents a progress in the theory of information processing by adding the particular case of the information related to promotional incentives found on the Internet by users with different Web experience levels. A series of conclusions are driven from its development, deepening the knowledge about how promotional incentives are processed on the Internet and what is their appropriate use according to users’ level of experience in surfing the Web.

Literature reviewThe impact of online sales promotion on consumer's attitudeRossiter and Percy (1997) state that the best sales promotion is the one capable of influencing both consumers’ attitude and behavior. The formation of attitudes toward an object entails a combination of cognitive beliefs and feelings toward it (Zanna & Rempel, 1988). These attitudes are stored in our memory and are available to the consumer, thus facilitating and favoring a good quality decision-making process.

It is therefore worth wondering whether online sales promotions really influence consumers’ attitude and to what extent. Taking traditional (offline) markets as a reference point, Inman et al. (1990) concluded that sales promotion affects the formation and change of consumers’ attitude. On the other hand, Petty and Cacioppo's classical Elaboration Likelihood Model (ELM, 1986) establishes two different routes for the formation of people's attitudes: the central route and the peripheral route. Under the central route, consumers assess information cognitively, actively and diligently, while under the peripheral route a person makes final decisions based on simple inferences or secondary aspects. According to the premises of this model, its authors argued that the messages capable of providing information signals to consumers would stimulate information processing under the central route (high level of message elaboration), while the messages that provide fewer information signals would lead consumers to process information under the peripheral route (low level of message elaboration). Therefore, the thoughts generated about the message will be transmitted to the brand in the form of beliefs or thoughts under central processing, and in the form of attitude toward the advertisement under peripheral processing.

In the light of these premises and given that online sales promotion is a communication tool able to convey a particular message about the brand, it is to be expected that the information it provides will influence consumers’ attitudes to a greater or lesser extent, depending on the type of processing involved. This processing will be influenced, in turn, by the type of promotional incentive involved (online discounts vs. gifts) (Chandon, Wansink, & Laurent, 2000; Jones, Reynolds, & Arnold, 2006; O’Curry & Strahilevitz, 2001; Palazón & Delgado, 2009), as well by the user's level of experience with the Web (San José-Cabezudo et al., 2007).

Online discounts and gifts processing. The moderating role of the experience in the use of InternetThe information processing and the assessment of a sales promotion will depend on the way of expressing promotional incentives (Nunes & Park, 2003; Palazón & Delgado-Ballester, 2013). If the incentive provided is difficult to convert to a common unit of measure, such like the case of online gifts, it will be more globally assessed, without the need of arithmetical calculations that provide the optimal solution. However, based on Nunes and Park's (2003) findings, it is to be expected that in the case of measurable incentives such as online discounts, individuals will perform analytical processing in order to calculate the net price of the product. This way, the assessment process of the sales promotion will be simplified, making it easier to calculate the value of the incentive promoted. Therefore, it seems clear that consumers will assess the sales promotion differently depending on how the incentive is expressed.

Impact of the type of promotional incentive and of experience with the Internet on the attitude toward the ad and the promotionIn the ELM terminology, the experience in the use of Internet is equivalent to the ability of processing (San José-Cabezudo et al., 2007). Based on the premises of this theory, we can affirm that the greater this ability is, the higher the probability that the individual will process the content of the message deeply and correctly (central route). On the contrary, the lower this ability is, the higher the probability of the message being processed under the peripheral route. Not all users will have the same processing ability, since surfing the Web requires certain knowledge and each individual has a different learning curve (Lie & Saarela, 1999). The complexity of this action will have a direct influence on the impact of the message (Stevenson, Bruner, & Kumar, 2000) and, therefore, on the impact of the online sales promotion. The need to perform guidance tasks in the means of communication will diminish the Internet user's capacity to process the promotional messages.

According to the authors, familiarity and experience with the means of communication will reduce the complexity and the number of elaboration tasks required by the individual, thus adding more value to the brand (Bruner & Kumar, 2000; Eveland & Dunwoody, 2002).

Therefore, the difficulty of processing information under the central route is higher for the individuals having little experience with the means of communication, which increases the likelihood that they use the simpler peripheral route (San José-Cabezudo et al., 2007; Thorbjornsen & Supphellen, 2004). Given that novice users are more likely to process online sales promotions under the peripheral route, it is to be expected that their attitude will be formed through the relationships established by the affect transfer model1 (Castañeda, Muñoz-Leiva, & Luque, 2007; Mackenzie et al., 1986; Sicilia, Ruiz, & Munuera, 2005). In exchange, experienced users will process online sales promotion mainly through the central route, which is why their attitude formation will be performed based on the dual mediation model2 (Castañeda et al., 2007; Mackenzie et al., 1986; Sicilia et al., 2005). This manner of assessing and processing information will influence the way the message affects attitude toward the advertisement containing the incentive, the website itself, the brand, and subsequently, the purchase intention (Bruner & Kumar, 2000; San José-Cabezudo et al., 2007; Thorbjornsen & Supphellen, 2004).

On the other hand, as experience with the use of Internet determines message processing, we can expect that it also influences the way each incentive affects advertisement attitude. In this regard, literature has made it clear that promotional messages can have a negative impact on the advertisement if it is perceived as intrusive. Since content relevance is essential for online users – especially for the goal-oriented ones – (Gallagher, Foster, & Parsons, 2001; Morrison, Pirolli, & Card, 2001; Thota, Song, & Larsen, 2010), we can expect that each incentive will affect users’ perception in a different manner, depending on their experience with Internet use. Expert users will be less willing to process stimuli coming from brands other than the regular one, especially because they are not willing to make additional effort to search and compare alternatives (Brynjolfsson, Dick, & Smith, 2004), unless the stimulus in question is able to reduce the effort needed for decision-making and to increase the process efficiency. Therefore, since discounts are easier to integrate in the consumer's usefulness function than gifts (Nunes & Park, 2003; Palazón & Delgado-Ballester, 2013), it is more likely that discounts affect expert user's attitude permanently.

The expert user will generate a positive advertisement attitude as long as the ad provides them with relevant and interesting contents and increases efficiency while they browse the website. We can therefore infer that online discounts generate better advertisement attitudes and a better attitude toward the sales promotion than online gifts. In exchange, and given that novice users are less used to online stimuli, they will react positively to both incentives, regardless of their nature, and both incentives will generate a positive advertisement attitude.

Based on all of the above, we suggest the following work hypotheses:H1a In the case of expert users, online discounts generate a better advertisement attitude than online gifts. In the case of novice users, there are no differences in the advertisement attitude between online discounts and online gifts.

As mentioned earlier, traditional media proved that the type of incentive offered affects the assessment of the sales promotion (Nunes & Park, 2003; Palazón & Delgado-Ballester, 2013) and that discounts, coupons and 2×1 offers are generally preferred (Shi, Cheung, & Prendergast, 2005). Besides, based on the Benefit Congruency Framework (Rossiter & Bellman, 2005), the higher the congruency between the product and the incentive offered, the better the assessment of said incentive. Hence, the incentives that are more congruent with the product and the benefit sought by the consumer will have a better assessment from the Internet user. Based on these findings, it is to be expected that the type of online incentive offered (discount vs. gift) will influence the attitude toward the online sales promotion and that this relationship will be moderated by the consumer's experience with the use of Internet.

As suggested, discounts are assessed in an analytical way, being integrated within the usefulness function as a reduction of the product's purchase cost and increasing the process efficiency. However, for this result to occur, cognitive operations must be performed, although not all Internet users can perform them. As some users need time to find their way on the Internet, they will have a lower capacity to perform the rest of cognitive operations (Bhatnagar & Ghose, 2004; Bruner & Kumar, 2000; Eveland & Dunwoody, 2002; Sicilia & Ruiz, 2010). This situation affects the impact of benefit congruency on the assessment and preference of the online promotion. Discounts require less cognitive effort from novice users as they navigate the Web. For this reason, even though discounts might be perceived by users as being more congruent with the product, they generate a less positive attitude toward the online promotion than gifts. Nonetheless, expert users’ processing and assessment of the discount will not require additional efforts, while providing them advantages that are more congruent with what they seek for than gifts. Online discounts will increase efficiency of the decision-making process and minimize the associated costs, thus generating a better attitude from expert users toward an online promotion containing discounts-based incentives as compared to gift-based incentives.

In the light of these premises, the following hypotheses can be established:H2a For expert users, online discounts generate a better attitude toward the sales promotion than online gifts. For novice users, online gifts generate a better attitude toward the sales promotion than online discounts.

The literature on sales promotion efficiency in traditional markets has concluded that discount-based promotions affect brand perception and assessment in a negative manner, since they make consumers attribute the purchase to the discount provided instead of to the product/brand quality (Davis, Inman, & McAlister, 1992).

However, not all the sales promotions can have this negative result for the brand (Inman et al., 1990). In the case of online gifts, sales promotions will help generate beliefs toward the brand unrelated to the price to be paid, which makes it more likely that its impact on the brand attitude will be positive. The higher the congruence between product and gift, the more positive the associations generated and, therefore, the more lasting the impacts of the promotion and the greater the likeliness that the gift will affect brand attitude (Rossiter & Bellman, 2005). These authors justify these findings by stating that a high level of congruence between product and incentive helps the brand provide information about the characteristics of the product or the benefits of its use. In other words, the gift offered will help the consumer build the brand image and generate brand equity (Buil et al., 2011).

However, as mentioned earlier, this process requires the performance of cognitive operations that novice users might not be able to perform due to their need of orientation on the Internet. Besides, it is more likely that novice users process information under the peripheral route, so the impact on the brand attitude will be more determined by how the message is displayed (peripheral signs) than by its content. For these users, the sales promotion type will not have a direct influence on the brand attitude, since they will mostly assess the way information is displayed, rather than the information itself.

However, as expert users need less orientation operations on the Web, they will be able to focus on the assessment of the provided stimuli systematically and thoroughly (Bhatnagar & Ghose, 2004; Sicilia & Ruiz, 2010), generating a different brand attitude depending on whether the online incentive is a discount or a gift. According to literature, non-monetary incentives – i.e. gifts – are the most appropriate ones for creating associations with the brand and, therefore, for having an impact on the brand attitude (Chandon et al., 2000; Palazón & Delgado, 2009).

Based on all of the above, the following hypotheses can be established:H3a For expert users, online gifts have a more positive impact on brand attitude than online discounts. For novice users, there is no direct effect of the online promotion type on brand attitude.

According to the ELM, users with a favorable attitude toward the message will generate a positive attitude toward the means of communication and the brand (Cho, 1999; Hershberger, 2003; Zhang, Kardes, & Cronley, 2002). It can therefore be said that a positive assessment of the online promotion from users will generate, in turn, positive ad and brand attitudes. Since the ability of processing and assessing contents on the Internet depends on prior Internet experience (Dahlén, 2002; Flavián-Blanco et al., 2012), it is to be expected that this variable moderates the existing relationship between attitude toward the sales promotion, the advertisement and the brand. Since expert users will process information mainly under the central route – due to their increased ability (Sicilia & Ruiz, 2010), and will surf the Web with an objective in mind, it is very likely that their attitudes will be formed through the central arguments of the advertisement, i.e. the promotional incentive. In exchange, in the case of novice users – who will process information mainly under the peripheral route due to their lack of online skills (Sicilia & Ruiz, 2010), the assessment of the advertisement will be based on its secondary or accessory elements and not so much on its content. In this case, the attitude toward the online promotion will affect less the advertisement attitude than in the case of expert users. Besides, the advertisement attitude will be one of the main variables of the brand attitude, as it has been proved that the secondary or accessory elements contained in the advertisement are among the main determinants of users’ attitude (e.g. music, color, images, etc.).

According to these arguments, we propose the following work hypotheses:H4 Attitude toward the online sales promotion affects advertisement attitude in a more positive way in the case of expert users than in the case of novice users. Attitude toward the online sales promotion affects brand attitude in a more positive way in the case of expert users than in the case of novice users. The advertisement attitude affects brand attitude in a more positive way in the case of novice users than in the case of expert users.

On the other hand, we can infer that the more favorable the user's attitude toward a website, the greater their attitude toward the advertisement displaying the promotional incentive and their brand attitude (Cho, 1999; Hershberger, 2003). The associations and opinions created toward the website in general will be transferred to the contents of said website and, subsequently, to the advertisements and brands it displays. Mandel and Johnson (2002) got to the conclusion that users create associations between the product, the brand and the design of the host website. As it occurs in traditional means of communication, on the Internet it is possible that a specific advertisement with a specific audience produces different effects when it is displayed on different mediums. This is explained by the fact that the credibility or reputation of the website displaying the advertisement might create inferences in the user's opinion about the quality of the content and the advertisements displayed on that website (Beerli, Martin & Padilla, 2009). Therefore, for both novice and expert users, the website credibility and reputation will affect in a positive way the opinion about the brand advertised and the banner displayed.

Based on the above premises, the following hypotheses can be drawn:H7 For both expert and novice users, attitude toward the website has a positive impact on the advertisement attitude. For both expert and novice users, attitude toward the website has a positive impact on the brand attitude.

At the behavioral level, academic literature has proven that the type of sales promotion also influences purchase intention. Discounts are more appropriate for inducing to acceleration, storage and increase of expenditure, while gifts seem more adequate for inducing to product testing (Shi et al., 2005). These authors found that on traditional markets, consumers’ favorite incentives and the ones with the highest impact on their purchase behavior were price discounts, 2×1 offers and discount coupons. However, Palazón and Delgado (2009) revealed that, when faced to a monetary and a non-monetary promotion, consumers do not have the need to justify their choice, so they always choose the promotion offering hedonic benefits, i.e. the non-monetary one.

Applying these results to the Internet, it is to be expected that different types of sales promotion affect users’ purchase intention differently, also depending on their Internet experience. Some authors have demonstrated that as the Internet use experience increases, the likeliness of making online purchases also increases (Kim & Park, 2005; Kuhlmeier & Knight, 2005).

However, there are authors who consider that, even though expert users have the necessary skills for processing messages more thoroughly, they do not always do so. Expert users are less responsive to unexpected stimuli (Dahlén, 2001) and less readily influenced by competitor stimuli (Bruner & Kumar, 2000). Bhatnagar and Ghose (2004), on their part, conclude that the more frequently individuals access the information on the Internet, the more likely it is that their behavior will be influenced by it. Therefore, the highest the frequency of Internet use, the higher the probabilities of being influenced by the information displayed on the websites and, subsequently, by corporate communication efforts. The Internet use experience provides familiarity with complex advertisement stimuli due to repeated exposure to them. However, the more time consumers spends on the Web, the more used they will get to the stimuli and more stimuli will be needed for obtaining a response (Hoffman & Novak, 1996).

In this sense, expert users will be less surprised by an online sales promotion than novice users and will be less responsive to it, thus requiring a more innovative stimulus to obtain a response. As mentioned earlier, the search for usefulness is the highest priority for expert users (Castañeda et al., 2007; Hammond, McWilliam, &Narholz, 1997; Novak, Hoffman, & Yung, 2000), which is why price discounts are considered to be more successful than online gifts at generating purchase intention. In short, novice users’ purchase intention will be equally affected by any type of online promotional stimulus, while the impact on expert users will depend on the type of stimulus displayed.

The following hypotheses can be drawn from all of the above:H9a For novice users, the type of promotional incentive (online discounts vs. gifts) will not affect their purchase intention differently. For expert users, discounts generate a higher impact on the purchase intention that online gifts.

To date, literature has made clear that advertisement attitude influences brand attitude (Briggs & Hollins, 1997; Dahlén & Bergendahl, 2001; Rettie, 2001; Ruiz & Sicilia, 2004) and purchase intention (Bruner & Kumar, 2000). Nonetheless, that influence depends on the Internet use experience, since that experience will directly and negatively impact the online advertisement efficiency in getting users’ attention, with novice users being the ones who are most aware of the advertisement. At the same time, since the perceived risk is higher among novice users (Korgoankar & Karson, 2007; Soopramanien, Fildes, & Robertson, 2007), getting users’ attention is not enough for influencing purchase intention directly, because the greater the perceived risk is, the lower the purchase probability will be (Barnes, Marateo, & Pixy Ferris, 2007; Forsythe & Shi, 2003; Korgoankar & Karson, 2007; Lassala, Ruiz, & Sanz, 2007; Tan, 1999). Novice users will seek brand security to reduce risk (Hoffman, Novak, & Peralta, 1999; Jarvenpaa, Tractinsky, & Vitale, 2000; Joines, Schere, & Sceufele, 2003; Kim, Ferrin, & Rao, 2008; Lee, 2001; McKnight, Choudhury, & Kacmar, 2002; Ruyter, Wetzels, & Kleijnen, 2001), as a prior condition for showing purchase intention in the online medium. For this reason, the advertisement attitude is considered to have a rather indirect impact on the purchase intention, through the brand assessment. However, since expert users trust their capacity to perform behaviors and make decisions online (Sánchez & Villarejo, 2004), it is to be expected that the online sales promotion will have a direct and positive influence on the purchase intention. The following hypotheses can be drawn from the above premises:H10 The impact of the advertisement attitude on the online purchase intention is higher among expert users than among novice users. The impact of the brand attitude on the online purchase intention is higher among novice users than among expert users.

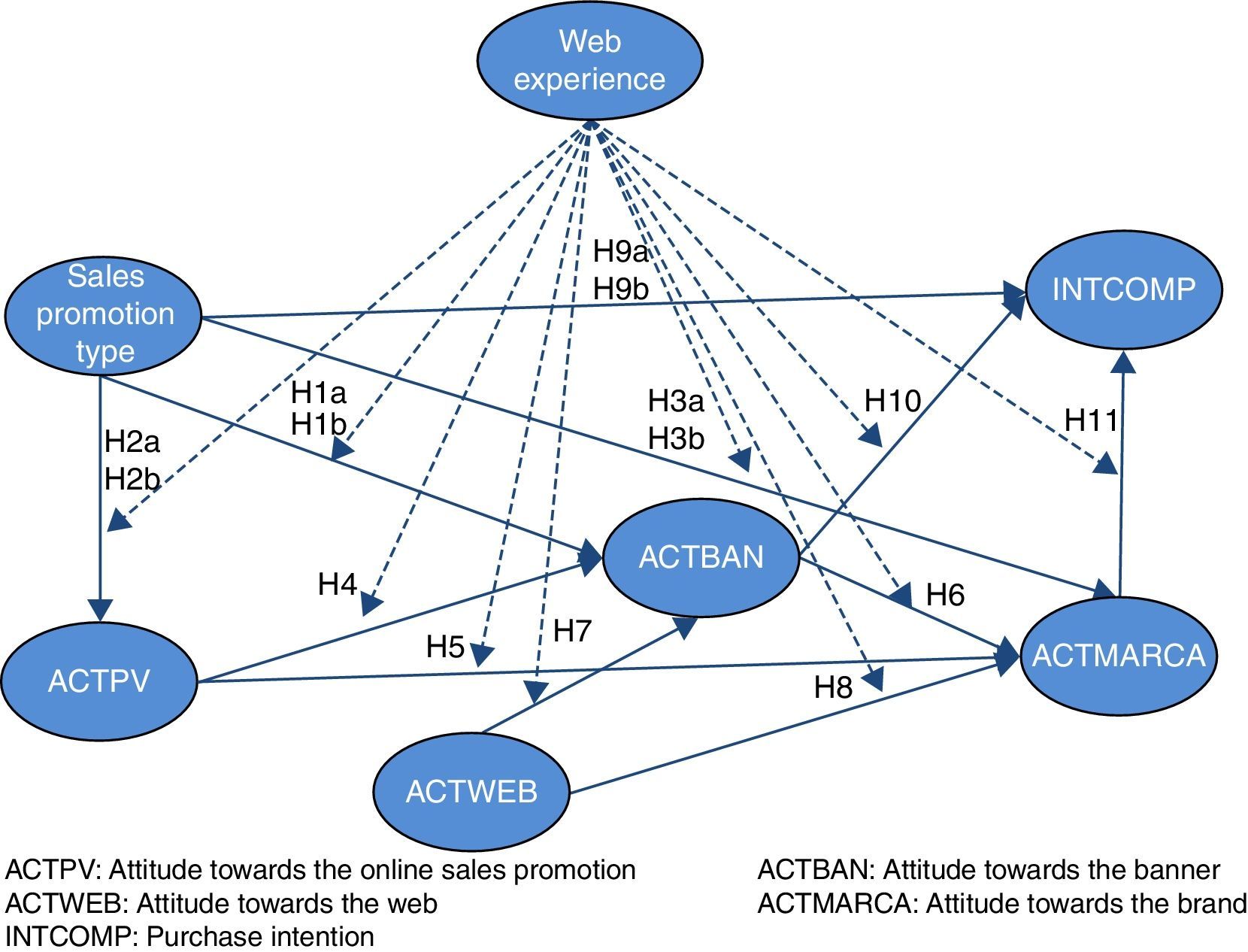

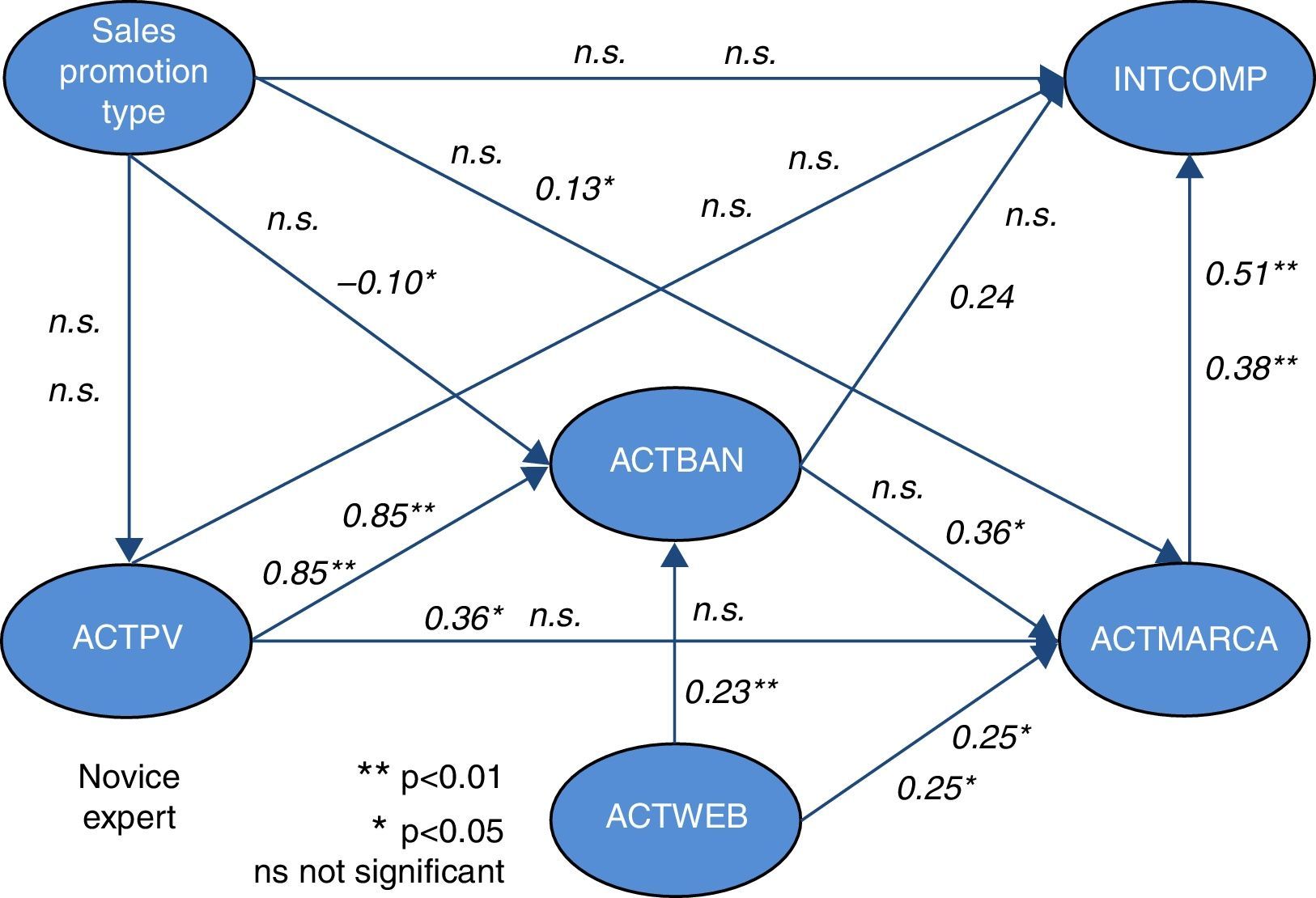

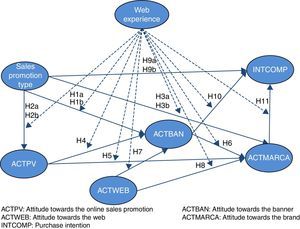

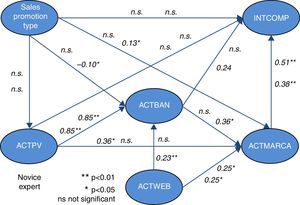

Based on the reviewed literature and the hypotheses suggested above, we propose a theoretical processing model for online sales promotions, which attempts to explain how the type of promotional incentive (online discounts vs. gifts) affects attitude formation and change, as well as Internet users’ purchase intention, all this moderated by users’ experience with the Internet (see Fig. 1).

Empirical studyAn experimental design was created to estimate the proposed theoretical model and compare the hypotheses, based on observations of individual behaviors and a computer survey.

Independent variablesThe independent variables were the type of online sales promotion (discount vs. gift) and the user's prior Internet experience (high vs. low). While the former is an a priori factor that allowed us to randomly assign individuals to the different promotional techniques considered in this study, the latter is considered to be a factor calculated a posteriori based on a series of objective and subjective measurements taken for each individual during the fieldwork.

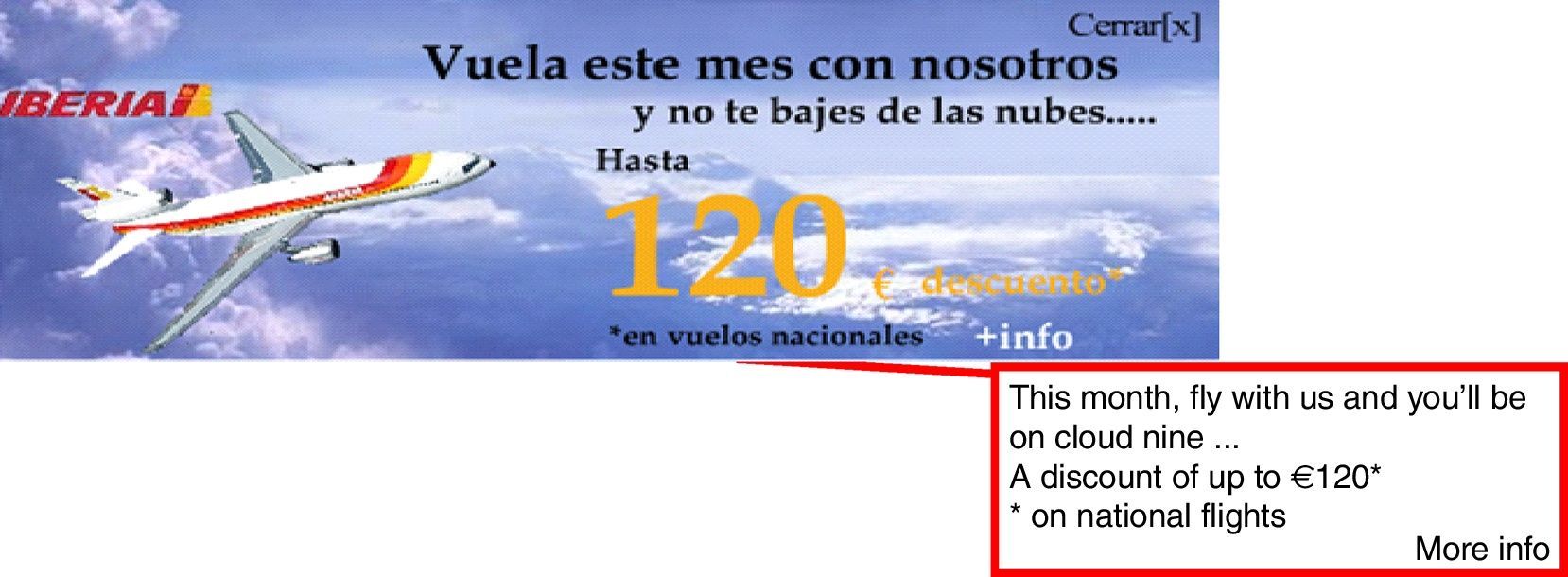

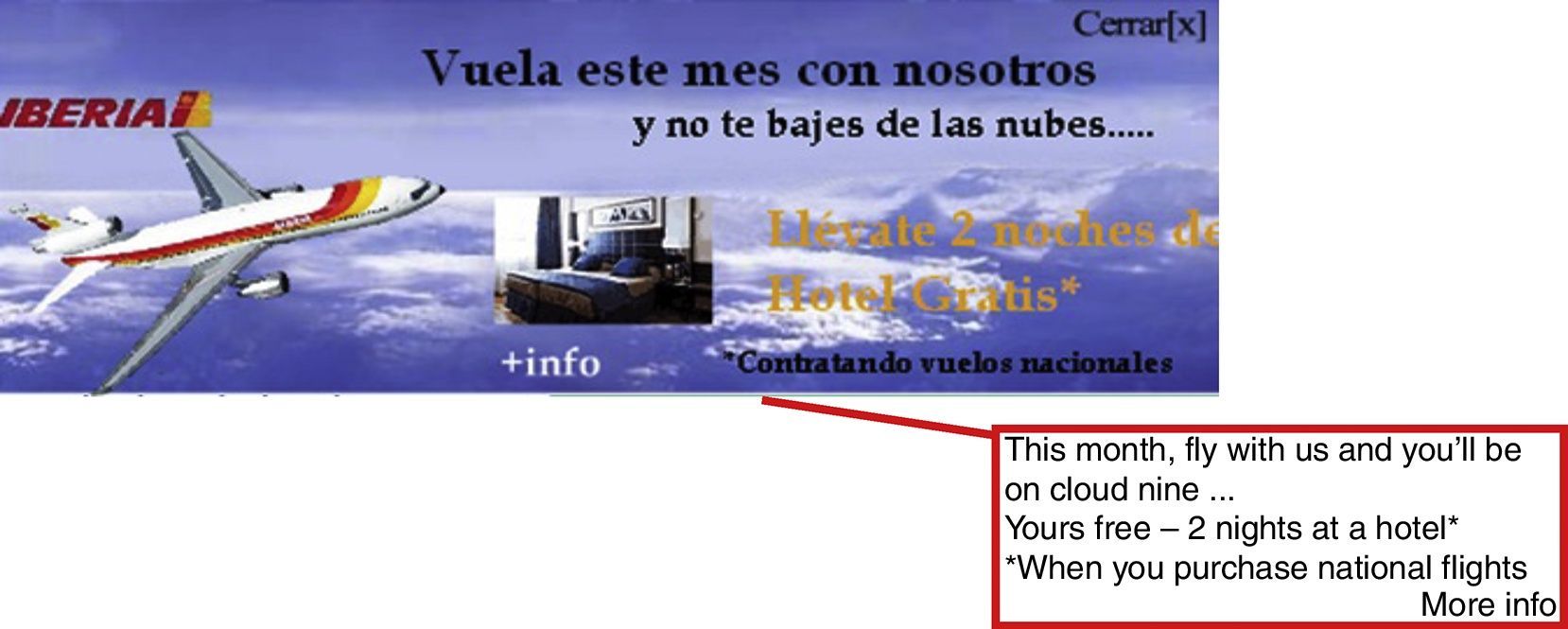

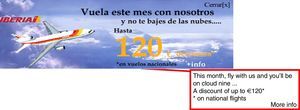

Product selection and design of promotional incentivesCertain criteria were taken into account to select the product category and brand based on the findings of similar prior studies (Alford & Biswas, 2002; Palazón & Delgado, 2011; Tan & Chua, 2004): the product category should be something that is purchased on a regular basis, with similar consumption levels for men and women and frequently offered promotional incentives; it should also be a product that is not considered to be totally hedonic or utilitarian to avoid the possible potential effects of congruence between the product and the incentive (Chandon et al., 2000; Nunes & Park, 2003). Therefore, the category “airline tickets” was selected as it complies with all the aforementioned requirements and is one of the most frequently purchased products on the Internet.

The Iberia brand was selected as it is well known among the target population and to avoid the possible effects of users’ potential aversion to risk on the final results.

We followed the recommendations of various authors to select the promotional incentives, establishing a monetary value for the incentive between 20% and 50% of the product's price (Alford & Biswas, 2002; Hardesty and Bearden, 2003; Nunes & Park, 2003; Tan & Chua, 2004).

Once the monetary value was established, incentives were selected based on the principle of compatibility (Tversky, Sattath, & Slovic, 1988), as congruent with the desired benefits for users and the selected product (Dowling & Uncles, 1997; Palazón & Delgado, 2009; Roehm, Pullins, & Roehm, 2002; Tversky et al., 1988).

For this study, we considered the work of various authors who have determined the main benefits of online purchases to be saving time and convenience3 (Atchariyachanvanich, Sonehara, & Okada, 2008; Castañeda et al., 2007; Dholakia & Uusitalo, 2002; McMeekin, Miles, Roy, & Rutter, 2000; Messenger & Narashiman, 1997; Morganosky & Cude, 2000).

We also considered the fact that airline tickets and hotel reservations are services that are often purchased together, according to various reports (IABSpain, 2013). We therefore selected a discount of 120€ for flight purchases as a monetary incentive and two free nights at a hotel as a non-monetary incentive.

Selection of the experimental websiteTo select the website used for the promotional experiment, we considered the Admetrics.com study (2013), which Iberia uses to focus their advertising efforts on dynamic banners that highlight prices, and the EyeBlaster report (2010), which concludes that airlines primarily use news, travel and economy-related websites to host their promotional banners. We finally opted to host the banners with promotional incentives on a news website, specifically, the El Mundo website (www.elmundo.es), as it is one of the most popular digital news sites in Spain.

Two layer-banners were created for each incentive (see Figs. 2 and 3). Due to the impossibility of actually using these experimental techniques on the actual El Mundo.es site, an expert I.T. engineer helped us create a website application that would capture the website in real time and redirect it to our own URL hosted on a different server, giving full autonomy to the experimental process. The website application consists of two frames – one that loads the Mundo.es site in real time, and the other to host the promotional processes. By combining the two, users see the experimental banners appear on the newspaper's website. Participants in the experiment were unable to distinguish that they were not actually on the official news website, since they were viewing the website's actual content in real time, without realizing that it was actually copied and redirected from another URL.

Pre-testIn order to verify whether the selected product was perceived as utilitarian or hedonic, a pre-test was conducted of 90 individuals, using the scale proposed by Batra and Ahtola (1990) and later applied by Spangenberg, Voss, and Crowley (1997) and Chandon et al. (2000). This scale measures the product's utilitarian component based on the following aspects: Practical/Impractical, Essential/Non-essential, while the hedonic component was measured with the following aspects: Fun/Boring, Pleasant/Unpleasant. Afterwards, an index was calculated to measure the difference between the average values of the utilitarian component and the average values for the hedonic component. Negative scores on said index indicate that the product is primarily hedonic while positive scores indicate that it is primarily utilitarian. The index obtained in this case was −0.1271, indicating that the utilitarian and hedonic components had a similar weight for the selected product category.

The pre-test demonstrated that the gift was perceived with the same value as the discount, using a t-test for a sample with a reference value of 120€ (p>0.5).

Experiment development and sample compositionThe experiment was conducted in two different Spanish provinces because, as a consequence of the type of product chosen, there could be possible differences in the responses of subjects residing in provinces with large or small airports. Considering the number of passengers registered in airports, we chose to conduct fieldwork in Madrid, where the country's main national airport is located, and another city with an airport listed at the bottom of the rankings according to the AENA annual report for 2010 (AENA, 2012). In order to avoid problems due to selecting subjects on the Internet and related issues of representation, the sample subjects (all Internet users) were selected randomly on the street rather than online, maintaining the percentages of sex and age proportionate to the Spanish population.

The experiment was conducted for one month in various selected cafés in the two cities. The fieldwork was conducted by an external service company specializing in market research under the researchers’ direct supervision. Once subjects were recruited, they were informed that they were going to participate in a study conducted by university researchers, without revealing the research objective, and they were invited into the café. Once inside the café, they were assigned to a workstation based on the aforementioned percentages, with a computer connected to the website and one of the experimental techniques, and were invited to navigate freely. All participants collaborated for free, and were not offered any incentives for their participation. After two minutes of navigation, the assigned layer-banner would appear on the upper right-hand part of the screen, moving downwards on the screen. At that time, users could either choose to interact with the banner, close it, or do nothing. In the first case, the online questionnaire would appear; otherwise it would appear automatically after 8minutes of navigation. The final sample consisted of 445 individuals, 57.5% of which were men and 42.5% were women, and 73.3% were between the age of 19–34, with the remaining 26.7% over 34 years old.

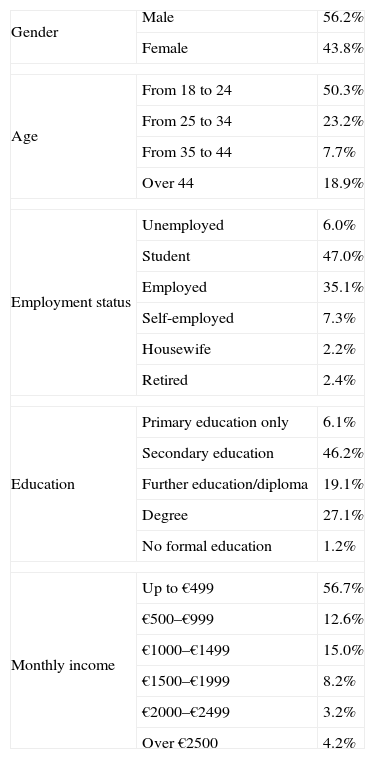

The final sample consisted of 445 individuals, 57.5% of which were men and 42.5% were women, and 73.3% were between the age of 19–34, with the remaining 26.7% over 34 years old. The majority had a monthly income under 1500€ and used e-mail and the Internet various times per week, every day, or various times per day (see Table 1).

Statistical description of the sample.

| Gender | Male | 56.2% |

| Female | 43.8% | |

| Age | From 18 to 24 | 50.3% |

| From 25 to 34 | 23.2% | |

| From 35 to 44 | 7.7% | |

| Over 44 | 18.9% | |

| Employment status | Unemployed | 6.0% |

| Student | 47.0% | |

| Employed | 35.1% | |

| Self-employed | 7.3% | |

| Housewife | 2.2% | |

| Retired | 2.4% | |

| Education | Primary education only | 6.1% |

| Secondary education | 46.2% | |

| Further education/diploma | 19.1% | |

| Degree | 27.1% | |

| No formal education | 1.2% | |

| Monthly income | Up to €499 | 56.7% |

| €500–€999 | 12.6% | |

| €1000–€1499 | 15.0% | |

| €1500–€1999 | 8.2% | |

| €2000–€2499 | 3.2% | |

| Over €2500 | 4.2% | |

To measure attitude toward the brand (ACTMARCA), a Likert scale was used with 4 items and 7 points developed by Mitchell and Olson (1981), which is widely used in relevant academic literature: 1. Iberia is a very good brand, 2. I like the Iberia brand, 3. Iberia is a very attractive brand, 4. Iberia is a quality brand.

The attitude toward sales promotions (ACTPV) was measured through a semantic differential scale of 4 items and 7 points proposed by Elliot and Speck (1998): 1. Not interesting/Very interesting, 2. Not fun/Very fun, 3. Not informative/Very informative, 4. Not credible/Very credible.

The attitude toward the website (ACTWEB) was also measured using a semantic differential scale of 3 items and 7 points proposed by Castañeda, Rodríguez, and Luque (2009): 1. Good/Bad, 2. Unfavorable/Favorable, 3. Negative/Positive.

On the other hand, the attitude toward the banner (ACTBAN) was measured using the scale proposed by Cho (2003) with 8 semantic differential items and 7 points: 1. I don’t like it/I like it, 2. I find it entertaining/I don’t find it entertaining, 3. It is not useful/It is useful, 4. It is not important/It is important, 5. It is not interesting/It is interesting, 6. It is not informative/It is informative, 7. I wouldn’t see this advertising banner again/I would see this advertising banner again, 8. It is not good/It is good.

Purchasing behavior was measured using a scale of purchase intentions (INTCOMP) applied to numerous studies by various authors, including Belch (1981) and Chatterjee and McGinnis (2010). The Likert scale of 7 points consisted of only one item: I intend to purchase the Iberia brand product the next time I buy an airline ticket.

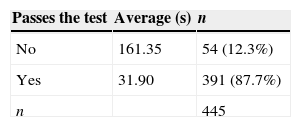

Lastly, a combination of different objective and subjective measurements was used to measure the subject's prior Internet experience. The subjective measures include asking the subjects a series of questions regarding the number of hours they spend per week navigating online, their frequency of use, and the type of online tools they use. The category for each of these variables was selected based on those established by the AIMC in the “General Media Study” and the “Internet User Survey.” In terms of the objective measures, immediately after concluding the experiment, and before leaving the room, the subjects were asked to search for information on the internet to respond to the following question: What is the diameter of a CD/DVD? The interviewees were encouraged to use all the available resources on the Internet to find the answer to this question, and the time they spent on this task was recorded. According to Yun and Lee (2001), the time (in seconds) each individual took to find the correct response is indicative of their skill level for using the Internet. A new variable was therefore established, called “Skill,” which determines the time (in seconds) each user took to find the answer to the question they were asked (see Table 2).

ResultsClassification of users according to Internet experiencePrior to estimating the proposed theoretical model and comparing the hypotheses, it was necessary to process the Internet experience variable in order to classify the individuals. We decided to conduct a Hierarchical Segmentation considering the aforementioned subjective and objective variables. The dependent variable was the participant's skill level using the Internet and the independent variables were the number of hours spent online per week, the frequency of Internet use and the types of tools used online. AID (Automatic Interaction Detection) was used as a segmentation algorithm. The analysis revealed two different groups of users: experts (56.5%) and novices (43.5%), although there were no significant differences between these two groups in terms of their relationship to the evaluated socio-demographic variables (p>0.10). Segment 1 (novices) was characterized by individuals unable to find the answer to the proposed question and those who took 37–70s to find it. These users spend less than 10h per week online and use one or two Internet applications (e-mail or navigation). Segment 2 (experts) consisted of users who found the correct answer in less than 37s, spend more than 10h per week online, use the Internet various times a day or every day, and frequently use more than 2 Internet applications.

Finally, a Kolmogorov–Smirnov test confirmed that there were no differences between the two groups in terms of the number of subjects exposed to each kind of promotional incentive (p>0.05). We therefore confirmed that the obtained results were not affected by any imbalance between the experimental techniques (discount vs. gift) for subjects with different levels of Internet experience. The tests also confirmed that there were no significant differences between the two groups in terms of the sociodemographic variables used to calculate the percentages (gender and age) (p>0.05). There were also no differences between the two groups in terms of the index measuring the perception of the nature of the product (utilitarian vs. hedonic) (p>0.10).

Estimate of the theoretical model and comparison of hypothesesAn SEM multi-group analysis (experts vs. novices) was used to estimate the theoretical model, as we had the appropriate conditions established by Jöreskog and Sörbom (1993). The type of online sales promotion was introduced in the model as a dummy variable considering the effects of the SEM analysis as a categorical variable. This implied that the estimated model would be conducted based on the ML robust estimation procedure (Satorra & Bentler, 1988, 1994) provided by Lisrel 8.8, mixing categorical and continuous variables and using the asymptotic covariance matrix as the weight matrix.

The obtained results indicated that the estimated model appropriately adjusted to the data, since the overall goodness of fit indicators were within the recommended limits. SB chi-square: 626.32 (d.f.: 343, p-value: 0.00); Normed chi-square: 1.83; RMSEA: 0.05; CFI: 0.98; Critical N: 288.77 (Del Barrio & Luque, 2012; Hair, Black, Babin, Anderson, & Tatham, 2005).

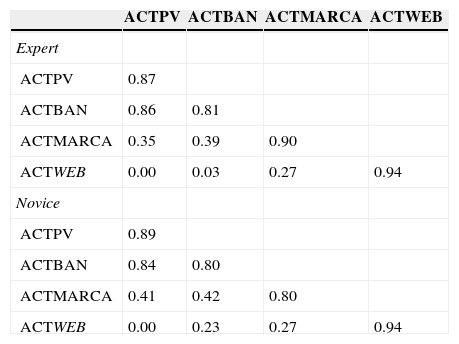

The measurement scales used presented good psychometric properties. All factorial loads were significant (p<0.05) with an individual reliability (R2) over 0.48 in all cases. The composite reliability (CR) and average variance extracted (AVE) indices were adequately over 0.70 and 0.50, respectively. Furthermore, the discriminant validity of the scales was used for each group, following the procedure recommended by Fornell and Larcker (1981), according to which the square root of the AVE must be greater than the correlation between the latent constructs (see Table 3).

Discriminant validity – square root of the AVE and correlations among constructs (by groups).

| ACTPV | ACTBAN | ACTMARCA | ACTWEB | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Expert | ||||

| ACTPV | 0.87 | |||

| ACTBAN | 0.86 | 0.81 | ||

| ACTMARCA | 0.35 | 0.39 | 0.90 | |

| ACTWEB | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.27 | 0.94 |

| Novice | ||||

| ACTPV | 0.89 | |||

| ACTBAN | 0.84 | 0.80 | ||

| ACTMARCA | 0.41 | 0.42 | 0.80 | |

| ACTWEB | 0.00 | 0.23 | 0.27 | 0.94 |

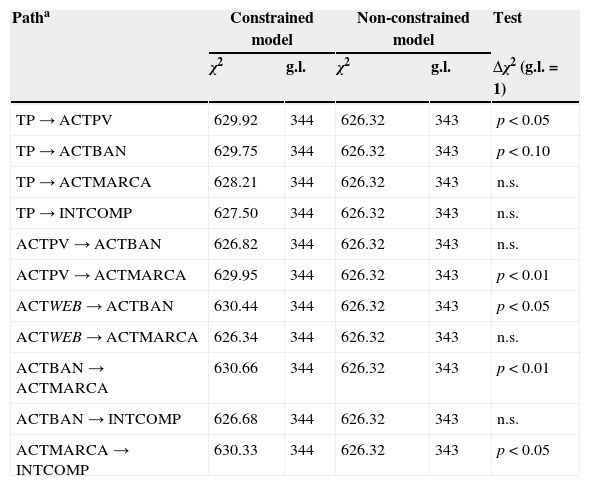

Fig. 4 shows the final estimated model for both groups, considering the standardized solution to be a common metric between the groups, as proposed by Jöreskog and Sörbom (2001). Our analysis of the results led to the first conclusion: Internet use experience moderates the way in which the Internet user processes information in online sales promotions and produces differential responses to online gifts and discounts. Table 4 shows the results of the invariance analysis4 between the parameters of the two groups using the chi-square test (Byrne, Shavelson, & Bengt, 1989; Satorra & Bentler, 2001).

Parameter test. Directs effects (differences between groups by χ2-test).

| Patha | Constrained model | Non-constrained model | Test | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| χ2 | g.l. | χ2 | g.l. | Δχ2 (g.l.=1) | |

| TP→ACTPV | 629.92 | 344 | 626.32 | 343 | p<0.05 |

| TP→ACTBAN | 629.75 | 344 | 626.32 | 343 | p<0.10 |

| TP→ACTMARCA | 628.21 | 344 | 626.32 | 343 | n.s. |

| TP→INTCOMP | 627.50 | 344 | 626.32 | 343 | n.s. |

| ACTPV→ACTBAN | 626.82 | 344 | 626.32 | 343 | n.s. |

| ACTPV→ACTMARCA | 629.95 | 344 | 626.32 | 343 | p<0.01 |

| ACTWEB→ACTBAN | 630.44 | 344 | 626.32 | 343 | p<0.05 |

| ACTWEB→ACTMARCA | 626.34 | 344 | 626.32 | 343 | n.s. |

| ACTBAN→ACTMARCA | 630.66 | 344 | 626.32 | 343 | p<0.01 |

| ACTBAN→INTCOMP | 626.68 | 344 | 626.32 | 343 | n.s. |

| ACTMARCA→INTCOMP | 630.33 | 344 | 626.32 | 343 | p<0.05 |

n.s.=not significant.

a Free estimate on non-constrained model.

The results led to the conclusion that novice users process the messages they receive according to the established classical model of independent influences5 while experts seem to do so according to the affect transfer model (Mackenzie et al., 1986). In other words, for novice users, the type of promotion viewed (discount or gift) does not seem to affect their formation of attitudes, as none of the established relationships were found to be significant. For these users, discounts and gifts generate similar attitudes toward the promotion itself, the banner and the brand (p>0.10). Nevertheless, for expert users, the type of online promotions affects their attitude toward the banner (β: −0.10; p<0.05) and the brand (β: 0.13, p<0.05). For these users, discounts produce a more positive attitude toward the banner than online gifts. However, gifts generate a more positive attitude toward the brand than online discounts. These findings confirm hypotheses H1a, H1b, H2a, H3a, and H3b, although H2b cannot be confirmed since both discounts and gifts generated a similar attitude toward sales promotions in novice users.

On the other hand, the attitude toward the sales promotion has a significant, direct effect on the attitude toward the banner for both groups (βNovices: 0.85; βExperts: 0.85; p<0.01), thereby confirming hypothesis H4. It also has a direct affect on the brand, but only in the case of novice users (βNovices: 0.36; p<0.05) and not for experts (p>0.10), confirming hypothesis H5 once again. As seen in Fig. 4, the relationship between attitudes toward the banner and the brand is significant for expert users (βExperts: 0.36; p<0.01), but not for novices (p>0.10), thereby confirming hypothesis H6 again. In other words, users’ feelings toward the banner are transferred to the brand only when they have experience using the Internet.

On the other hand, the relationship between the website and the promotional banner was not significant for experts (p>0.10), which means that these users do not appear to transfer their feelings about the website to the banner. However, novices did produce attitudes toward the banner as a result of their opinion of the hosting website (βNovices: 0.23; p<0.01). These results led us to reject hypothesis H7. The attitude toward the website did seem to affect the attitude toward the brand, in the case of both experts (βExperts: 0.25; p<0.05) and novices (βNovices: 0.25; p<0.05), and there were no significant differences between groups (p>0.10), confirming hypothesis H8. In other words, the user's Internet experience does not affect the relationship between the attitude toward the website and the brand.

Furthermore, the type of promotion viewed (discount vs. gift) does not affect the purchase intentions for either group (p>0.10). Both groups of individuals (experts vs. novices) present a purchase intention level similar to online gifts and discounts, rejecting hypotheses H9a and H9b. However, purchase intentions have a direct, quasi-significant influence on attitudes toward the banner, but only in the case of novice users (βNovices: 0.24; p<0.10) and not in the case of experts (p>0.10), confirming hypothesis H10.

Finally, in regard to the relationship between the influence of attitude toward the brand on purchase intentions, the results show that said relationship is significant for both novice and expert users, although greater for novices (βNovices: 0.51; βExperts: 0.38; p<0.01), thereby confirming hypothesis H11.

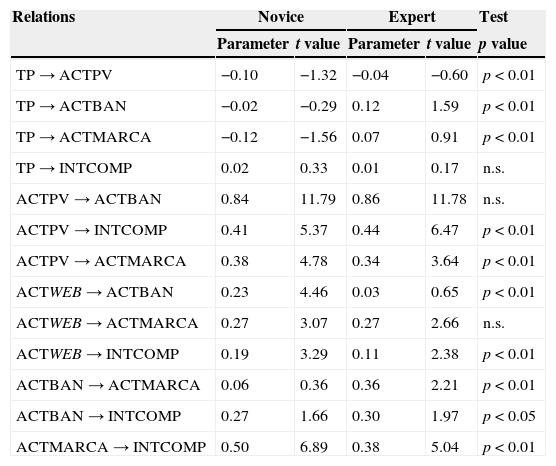

In order to study whether the previous results are true in terms of direct effects when the analysis of the relationships between the proposed variables is conducted in terms of the total effects (direct and indirect), we conducted a test of the differences of the total effects, which showed similar results (see Table 5).

Non-standardized total effects. Differences between groups (t-test).

| Relations | Novice | Expert | Test | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | t value | Parameter | t value | p value | |

| TP→ACTPV | −0.10 | −1.32 | −0.04 | −0.60 | p<0.01 |

| TP→ACTBAN | −0.02 | −0.29 | 0.12 | 1.59 | p<0.01 |

| TP→ACTMARCA | −0.12 | −1.56 | 0.07 | 0.91 | p<0.01 |

| TP→INTCOMP | 0.02 | 0.33 | 0.01 | 0.17 | n.s. |

| ACTPV→ACTBAN | 0.84 | 11.79 | 0.86 | 11.78 | n.s. |

| ACTPV→INTCOMP | 0.41 | 5.37 | 0.44 | 6.47 | p<0.01 |

| ACTPV→ACTMARCA | 0.38 | 4.78 | 0.34 | 3.64 | p<0.01 |

| ACTWEB→ACTBAN | 0.23 | 4.46 | 0.03 | 0.65 | p<0.01 |

| ACTWEB→ACTMARCA | 0.27 | 3.07 | 0.27 | 2.66 | n.s. |

| ACTWEB→INTCOMP | 0.19 | 3.29 | 0.11 | 2.38 | p<0.01 |

| ACTBAN→ACTMARCA | 0.06 | 0.36 | 0.36 | 2.21 | p<0.01 |

| ACTBAN→INTCOMP | 0.27 | 1.66 | 0.30 | 1.97 | p<0.05 |

| ACTMARCA→INTCOMP | 0.50 | 6.89 | 0.38 | 5.04 | p<0.01 |

Despite the popularity of online promotional incentives for business practices, there are very few academic studies that study how these incentives are processed, and more specifically the differences in processing online discounts and gifts. We also have not found any scientific studies analyzing whether the level of users’ Internet experience moderates said processing. This study is intended to breach the existing gap in the academic literature on this subject.

The results have demonstrated that online discounts and gifts have a different effect on the consumer's response and that the users’ Internet experience moderates said relationship. Specifically, offering an online discount or gift affects consumers’ attitudes and purchase intentions. This influence on their attitudes and behavior has been shown to be positive in all cases. The study also demonstrates that online discounts and gifts are processed differently depending on whether the Internet user is an expert or a novice. While novice users process both types of online incentives similarly, expert users process the information more or less in-depth depending on whether they are offered an online discount or gift. We have also determined that during the promotional period, online sales promotions act as a limiting factor for negative thoughts about the brand, obtaining positive evaluations in all cases. Therefore, our first interesting conclusion from this study is that, in the case of online sales promotions, the users’ attitudes toward said promotions do not seem to negatively affect the brand, unless said attitudes toward the promotion are negative.

The study also concludes that the promotional incentive used determines the attitude toward the banner and the registered brand, however it does not affect purchase intentions or the attitude toward the sales promotion itself. Both incentives (gift vs. discount) generate positive attitudes toward the sales promotion and high purchase intentions.

On the other hand, we have found that Internet experience affects the relationship between the types of online incentive offered, attitudes toward the banner, and attitudes toward the brand. Both the discount and the gift have a similar effect on the attitude toward the banner and the brand for novice users. However, online discounts are more effective than gifts to improve attitude toward the banner in the case of expert users. In contrast, their attitude toward the brand is stronger when they view an online gift despite the fact that, initially, we would expect the user's Internet experience to not affect the direct relationship between the type of online sales promotion and purchase intentions. Both groups (novices vs. experts) developed similar purchase intentions when viewing each of the promotional incentives. We also did not find any differences in the relationship between the attitude toward the sales promotion and the attitude toward the banner. Both novices and experts largely transfer their opinions and attitudes toward the sales promotion to the viewed banner. However, Internet experience does seem to affect the relationship between the attitude toward the sales promotion and the attitude toward the brand, since novice users transfer more feelings toward the brand than experts. This result is coherent with the ELM model. Assuming that novices have more cognition necessities than experts, novices most likely develop more opinions about the brand based on the online discount or gift. However, due to the perceived risk, novices present lower purchase intentions than experts with the same promotional stimuli.

The study demonstrated that direct transfer between the banner and the brand only occurs with expert Internet users and not novices, most likely due to what Bhatnagar and Ghose (2004) and Sicilia and Ruiz (2010) have established, that experts have more resources available for processing this information, and most likely process said information more in-depth. Therefore, the effect on attitudes is greater for experts than for novices. However, the findings of this study contradict those established by Hershberger (2003) also in an online environment, since, according to this author, novice users are more prone to changing their attitudes than experts as a result of being exposed to online stimuli.

In regard to the precedents of online purchase intentions, the variable that initially determines novice users’ purchase intentions is their attitude toward the brand, followed by their attitude toward the promotion, the banner, and lastly the website. However, for expert users, the main variable affecting online purchase intentions is their attitude toward the sales promotion, followed by the opinion about the brand, the banner, and lastly, the website.

Therefore, novice Internet users seem to make purchases guided primarily by the offered brand, although the promotional incentive, as well as the banner and the website, further reinforce purchase intentions. However, for expert users, the offered online sales promotion is the main determining factor in making a purchase. Experts are also much more affected by how said sales promotion is communicated (banner) and much less by the brand and the website than novices. We can therefore conclude that the presentation and communication format of the online sales promotion is fundamental for expert users, since the viewed banner is one of the factors that affects their purchase intentions.

However, as previously mentioned, in the case of novices, the online advertisement has a direct effect on their online purchase intentions, although this does not occur with experts. The main reason behind these results is that novice users are less used to the stimuli of Internet communications, which more easily affects purchase intentions than in the case of experts. Nevertheless, said influence is not as powerful as the brand's influence, since these users have less confidence in their ability to process information on the Internet. This feeling leads them to try to make sure they do not make any mistakes. They therefore risk less and, consequently, are less likely to be guided by commercial offers and more by the brand offering said promotions as a guarantee of success. Expert users have more confidence in their abilities to process online information and to evaluate an online commercial offer, which is why they have a greater response to communication stimuli on the Internet.

Management recommendationsConsidering these findings for attracting the attention of Internet users, it is highly recommended to use well-designed promotional incentives that are adapted to the users’ Internet experience. This will undoubtedly help the company distinguish itself from the competition and generate added value for the client. To achieve this objective, it is necessary to know the users’ levels of Internet experience beforehand in order to design a promotional incentive adapted to their needs. This is clearly a complicated task, although in the past decade, and more specifically in the past few years, the development of information sources regarding the online environment has allowed us to discover audience profiles for hundreds of thousands of websites based on Internet users’ demographic characteristics, lifestyles and behavior patterns. On a global scale, companies such as comScore have developed pioneer tools for measuring website audiences, for example MMX, which obtains data from 49 European markets through panels of thousands of Internet users, or Digital Analytix, which combines the data from panels with the analytics data from the website servers. This information is used by companies nowadays to develop their digital media plans, offering a high degree of flexibility in terms of website selection and especially the type of user viewing a certain banner, or others, based on variables such as age, the components or plug-ins installed in their equipment, the number of times they access the website, and their Internet navigation speed (which are all determining factors of the user's Internet experience).

For more novice users, it is recommended to launch online sales promotions only for those who have prior knowledge of the brand since their opinion about said brand is the greatest determining factor in their future purchase intentions. We also recommend selecting and designing the promotional incentives very carefully in an attempt to transfer the appropriate brand characteristics, since for this kind of novice, their opinion about the online sales promotion has a direct, positive effect on the brand.

To improve the attitude toward the brand, online gifts are recommended as a promotional technique, since these have a greater influence on the opinion of the brand when users are either experts or novices. However, if the company's objective is simply to get the user to purchase a product/service, price discounts are recommended.

Based on all of the above, we recommend designing dynamic promotional banners with very attractive visual content and very clear, concise information, in line with the promotional stimuli used in this study. The content of the promotional banner should very clearly show the aspects users should remember, as well as those that would motivate them to initiate certain behaviors. Promotional banners should be designed to be as attractive as possible to draw the Internet user's attention without bothering them, in order to attract their attention away from the navigation process.

It is also important to carefully select the website used to communicate the promotional incentives, since it has been demonstrated that the opinion about the website affects both future purchase intentions and the attitude toward the brand and the banner. Therefore, websites should be selected according to the consumer's tastes in order to generate positive attitudes, since said attitudes will transfer to the brand and purchase intention.

Limitations and future lines of researchWe are aware of certain limitations of this study that should be taken into consideration for future research. The primary limitations include the following: a quasi-experimental design was created that used purchase intention behavior as the final variable instead of real purchase behavior. Working with purchase intentions as an indicator of real behaviors may lead to overestimating some of the obtained results. Various situations in the environment as well as a change in the consumer's characteristics could consequently lead them to not purchase the product; therefore, future research could try to reconsider the experimental design in order to simulate a real purchase situation. The measurement of said variable has not been expressly specified for the acquisition of the online sales promotion. This may result in certain individuals exhibiting purchase intentions that were not motivated by the sales promotion in question.

Another limitation may arise from the congruence between the brand and the incentive. As explained in this study, said congruence may affect the user's attitudes toward the sales promotion and the brand. Since the degree of congruence was not measured, it is possible that the results were affected; however, although the degree of congruence was not measured, the incentives were designed to be as similar as possible to the brand's general manner of using this tool. Another limitation is related to the actual tool used to communicate the incentives: a layer-banner. The high degree of intrusiveness may also have affected the users’ perceptions about the banner, therefore affecting the results of this study. Nevertheless, it should be taken into account that the type of banner used was exactly the same for both types of promotional incentives.

Limitations may also occur from the generalization of the obtained results due to the use of only one product category and brand. Future research should focus on other categories of products and/or services in order to improve the generalization of the results.

Lastly, future lines of research could also study how the results obtained in this study may vary based on the type of tool used to communicate the promotional incentives, Display Ads (such as in the case of our study) versus Search Engine Ads, which is a less intrusive advertising format and more natural in the actual navigation process.

As explained in this study, the congruence between the brand and the selected incentive could affect the results obtained by the selected sales promotion. It is therefore essential to propose future research to analyze situations of congruence or a lack of congruence between the brand and the incentives in order to study the effect on the results.

The affect transfer, dual mediation and independent influence models are an attempt to define the way brand and advertisement cognition interact with attitude toward the ad and the brand, as well as with the purchase intention the brand advertised (MacKenzie, Lutz, & Belch, 1986). In particular, the affect transfer model establishes that advertisement attitude indirectly affects purchase intention through brand attitude; at the same time, advertisement attitude will affect brand attitude.

According to the dual mediation model, brand cognition and brand attitude act as a mediator in the relationship between advertisement attitude and purchase intention. In other words, advertisement attitude affects brand cognition and brand attitude. This model states that the advertisement attitude affects both the way of coding the information provided in the ad and the consumers’ inferences about the brand, this effect being reflected in the thoughts they develop during the information processing.

This term is understood as the additional benefits perceived by consumers derived from attributes such as the establishment's location, 24h availability of the service, saving time, compatibility with the lifestyle, and privacy (Rugimbana, 1995; Rugimbana & Iversen, 1994).

The invariance test of parameters consists of first estimating the model for both groups, leaving the parameters open between constructs (unrestricted model). After, the model is estimated again, setting the parameter being compared equally between the groups (restricted model). The last step consists of performing a chi-square test to establish the differences between the restricted and unrestricted models (g.l.=1) to determine whether said difference is significant (p<0.05). The chi-square comparison was conducted following the procedure proposed by Satorra and Bentler (2001) for situations lacking data normality.

The model of independent influences proposes a direct influence of attitude toward the advertisement on purchase intentions and independent of the influence of attitude toward the brand (Mackenzie et al., 1986).