Previous research supports the relationship between the use of alcohol and other drugs and mental disorders. The aim of this study was to analyse the association between drug and alcohol use prior to incarceration and the current prevalence of mental disorders among the incarcerated population in Spain.

Material and methodsA cross-sectional study was conducted, including to 2709 incarcerated subjects (2484 males and 225 females) from a total of 8 prisons. A self-administered anonymous and voluntary questionnaire was used. The prevalence of psychoactive substance use prior to imprisonment and the current prevalence of mental disorders was calculated. The association between the two variables was analysed with logistic regression for both genders.

ResultsAlcohol was the most consumed substance in the 6 months prior to detention for both men and women (68.5 and 48.9%, respectively) followed by cannabis (50.9 and 38.2%, respectively). The prevalence of mental disorders in prison was statically significant for men and women (24.9 and 34.2%, respectively). Most of the psychoactive substances analysed involve a risk factor for current mental disorder, especially as regards the use of psychotropic drugs (OR: 2.04, 95% CI: 1.54–2.71) and cannabis (OR: 1.81, 95% CI: 1.47–2.24).

DiscussionWe found an association between alcohol and drug use and the current prevalence of mental disorders among the incarcerated population sample. Furthermore, it is recommended to develop effective protocols for treatment and rehabilitation programmes in prison. These should suit inmates’ history of drug and alcohol use to improve mental health strategies.

Investigaciones previas apoyan la relación entre consumo de alcohol y otras drogas y trastornos mentales. El objetivo de este estudio fue analizar la asociación entre consumo de alcohol y otras drogas previo al internamiento en prisión y la prevalencia actual de trastornos mentales entre la población penitenciaria de España.

Material y métodosSe realizó un estudio transversal sobre 2.709 personas privadas de libertad (2.484 hombres y 225 mujeres) distribuidos en 8 centros penitenciarios. Se utilizó una encuesta autoadministrada anónima y voluntaria. Se calculó la prevalencia de consumo de sustancias psicoactivas previamente a prisión y la prevalencia actual de trastornos mentales. La asociación entre ambas variables se analizó con regresiones logísticas para ambos géneros.

ResultadosEl alcohol fue la sustancia más consumida en los 6 meses previos al internamiento tanto para los hombres como en las mujeres (68,5 y 48,9%) seguido del cannabis (50,9 y 38,2%). La prevalencia de trastornos mentales en prisión fue estadísticamente significativa para los hombres y mujeres (24,9 y 34,2%, respectivamente). El consumo de la mayoría de las sustancias psicoactivas analizadas supuso un factor de riesgo para tener actualmente algún trastorno mental, con especial relevancia del consumo de psicotrópicos (OR: 2,04 IC95%:1,54-2,71) y cannabis (OR: 1,81 IC95%:1,47-2,24).

DiscusiónSe encontró una asociación entre consumo de alcohol y drogas y la prevalencia actual de trastornos mentales entre la población penitenciaria estudiada. Asimismo se recomienda desarrollar programas de tratamiento y rehabilitación en prisión adecuados a las historias previas de consumo para mejorar las estrategias de salud mental.

The use of alcohol and other drugs among the prison population prior to imprisonment is an international problem, with a high prevalence of use being found in prior research projects conducted in the United States,1 South America,2 Europe3 and Asia4 with prevalences that range approximately from 20% to 80%. In a prior meta-analysis5 analysing a total of 30 studies, the prevalence of alcohol abuse was 18–30% and 10–24% among men and women, respectively, and 10–48% and 30–60%, respectively, at the time of imprisonment.

According to data provided by the European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction,3 approximately 60% of European inmates had a drug abuse problem at some point in their life prior to their imprisonment, highlighting cannabis with prevalences ranging from 12% to 70% depending on the country considered. In addition, occasionally the use and/or abuse of drugs continues during the fulfilment of the prison sentence.6

In Spain, the Survey on Health and Drug Use among Inmates in Penitentiary Institutions7 highlights alcohol use as the predominant substance in the month prior to imprisonment with approximately 65%, followed by cannabis (40%), and cocaine in powder and base form (27% and 18%, respectively).

A multitude of previous international investigations show a high prevalence of mental disorders in prison,8–10 being higher than those found in the general population.11 In one meta-analysis8 conducted in prisons of 24 countries and more than 33,500 inmates, a general prevalence for depression of 10.2% was estimated among men and 14.1% among women. Regarding the characteristics of the mental disorders, most research projects agree that anxiety and depression disorders are the most common for both sexes,11–13 with prevalences ranging from 20% to 60% among men and 40% to 60% among women. In Spain, in the report from the Ministry of the Interior14 from the year 2006, it was estimated that the prevalence of mental disorders within Spanish prisons was approximately 46%. In another investigation in Spain15 on 707 inmates, it was observed that the prevalence of psychiatric pathology is higher in the penitentiary population than in the general population; the data reveal that approximately 40% have some disorder on Axis I in the DSM-IV.

The penitentiary population shows a high comorbidity between drug use disorders and various mental disorders.9,16 In an investigation conducted among female inmates in the United States,16 statistically significant associations were found between a mental disorder (OR: 2.4), severe depressions (OR: 2.7) and schizophrenia (OR: 2.4) with the abuse of alcohol and other drugs prior to prison. These data are in line with research projects conducted in prisons in France,17 Italy18 or Spain.19

Based on the previous literature analysed, we start from the hypothesis that inmates with a history of alcohol and other drug use will show a higher prevalence of mental disorders than inmates with no history of alcohol and drug use. In order to test this hypothesis, the following main objectives are established: (a) to learn the prevalence of the use of alcohol and other drugs prior to imprisonment; (b) to learn the prevalence of mental disorders among the study penitentiary population and (c) to analyse the possible association between the use of alcohol and other drugs prior to prison and mental disorders among the penitentiary population.

Materials and methodsParticipants and procedureAnalytical, cross-sectional study based on the population of 8 penitentiary centres in Spain: Murcia I, Murcia II, Alicante I, Alicante II, Granada, Cuenca, Albacete and Ocaña (No.=259). These prisons house a total of approximately 5200 male inmates (approximately 8.3% of the total prison population in Spain). The collection of information was conducted between January and August 2014 through self-administered surveys among the inmates.

The study population was the set of inmates of both sexes who met the following inclusion criteria: (a) able to read and write in Spanish, (b) participating voluntarily and (c) signing the informed consent form attached to each survey. Among the people who met the inclusion criteria, the inmates were randomly selected. At first it started with the prisons in the Community of Murcia, being expanded to prisons of different sizes until a representative sample (approximately 50%) was obtained. The size of the final sample was 2709 inmates (2484 men [79.8% convicted and 20.2% preventive] and 225 [84% convicted and 16% preventive] women), representing 49.2% of the total population in the study prisons.

Participants were divided into groups of approximately 20 people in the common areas in each of the modules where the research was conducted. The duration per group was approximately 30–45min with the surveys being self-administered. The research was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Universidad de Murcia and the Support Unit of the General Secretariat of Penitentiary Institutions. All inmates had to sign an informed consent prior to their participation that included relevant information about the research; not participating in the study did not pose any disadvantage for the participants.

InstrumentSociodemographic and penitentiary dataData were collected regarding age, nationality, current marital status, level of education reached, pre-prison employment situation, recidivism in prison and type of offence that gave rise to imprisonment.

Mental disorders in prisonIn order to determine the prevalence of different mental disorders in prison, the items were adapted from previous research conducted in prisons in New Jersey.20 Specifically, the questions were: “At present, are you receiving treatment diagnosed by a specialist for anxiety?”, “At present, are you receiving treatment diagnosed by a specialist for depression?”, “At present, are you receiving treatment diagnosed by a specialist for schizophrenia?” and “At present, are you receiving treatment diagnosed by a specialist for bipolar disorder?”. Inmates who responded positively to any of the above issues were categorised as currently receiving treatment for a mental disorder.

Pre-prison use of alcohol and other drugsAdapted from a prior research project3 and through 8 questions, they had to state “yes or no” to the use of the following substances during the 6 months prior to their current imprisonment: alcohol, cannabis, cocaine (powder and/or base), heroin, psychotropics (without medical prescription), LSD and/or ecstasy.

Statistical analysisIn the first step, the bivariate analysis of socio-demographic and criminal variables was performed based on sex. Later, the prevalence of substance use on the basis of sex during the 6 months prior to imprisonment was estimated. In the bivariate comparisons between men and women, the analysis of χ2, or the Student's t-test, was used, depending on the nature of the variables analysed. Finally, by means of logistic regressions, the odds ratios (OR) were calculated on the basis of sex and adjusted for all psychoactive substances consumed before prison. Data analysis was performed using the SPSS statistical package (version 20.0) considering in the statistically significant comparisons a p-value of <0.050.

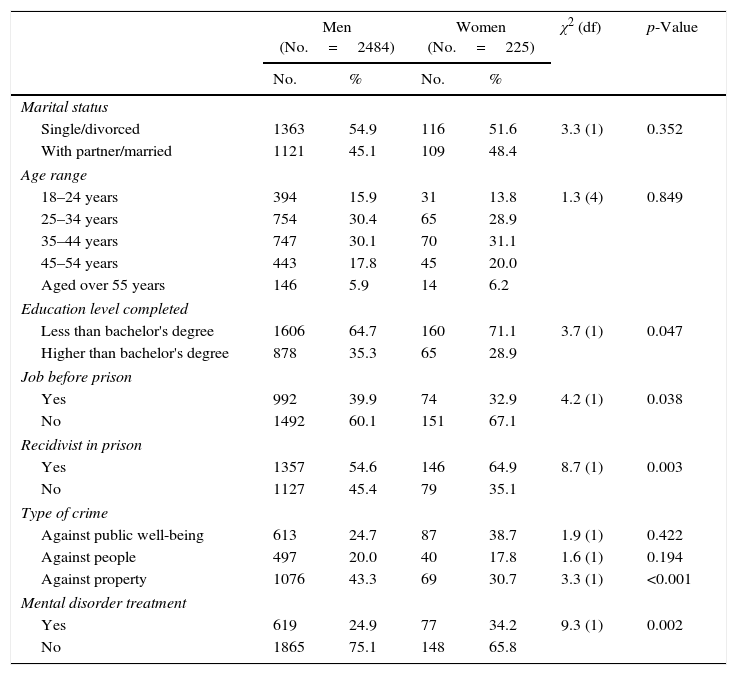

ResultsTable 1 shows the distribution of the socio-demographic and penitentiary variables of the participants according to the gender of the inmate (91.6% men and 8.4% women). Differences were found on the basis of sex, so the male group showed a higher educational level reached and a lower level of pre-prison unemployment. On the basis of the criminal variables, the number of recidivists in prison was higher in the female group, notably crimes against public well-being, with crimes against property being the predominant crime among males. Finally, it was observed that the number of women who are currently receiving treatment in prison for a mental disorder is higher than that of men (34.2% versus. 24.9%, respectively).

Socio-demographic and penitentiary characteristics according to sex.

| Men (No.=2484) | Women (No.=225) | χ2 (df) | p-Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | |||

| Marital status | ||||||

| Single/divorced | 1363 | 54.9 | 116 | 51.6 | 3.3 (1) | 0.352 |

| With partner/married | 1121 | 45.1 | 109 | 48.4 | ||

| Age range | ||||||

| 18–24 years | 394 | 15.9 | 31 | 13.8 | 1.3 (4) | 0.849 |

| 25–34 years | 754 | 30.4 | 65 | 28.9 | ||

| 35–44 years | 747 | 30.1 | 70 | 31.1 | ||

| 45–54 years | 443 | 17.8 | 45 | 20.0 | ||

| Aged over 55 years | 146 | 5.9 | 14 | 6.2 | ||

| Education level completed | ||||||

| Less than bachelor's degree | 1606 | 64.7 | 160 | 71.1 | 3.7 (1) | 0.047 |

| Higher than bachelor's degree | 878 | 35.3 | 65 | 28.9 | ||

| Job before prison | ||||||

| Yes | 992 | 39.9 | 74 | 32.9 | 4.2 (1) | 0.038 |

| No | 1492 | 60.1 | 151 | 67.1 | ||

| Recidivist in prison | ||||||

| Yes | 1357 | 54.6 | 146 | 64.9 | 8.7 (1) | 0.003 |

| No | 1127 | 45.4 | 79 | 35.1 | ||

| Type of crime | ||||||

| Against public well-being | 613 | 24.7 | 87 | 38.7 | 1.9 (1) | 0.422 |

| Against people | 497 | 20.0 | 40 | 17.8 | 1.6 (1) | 0.194 |

| Against property | 1076 | 43.3 | 69 | 30.7 | 3.3 (1) | <0.001 |

| Mental disorder treatment | ||||||

| Yes | 619 | 24.9 | 77 | 34.2 | 9.3 (1) | 0.002 |

| No | 1865 | 75.1 | 148 | 65.8 | ||

df: degrees of freedom.

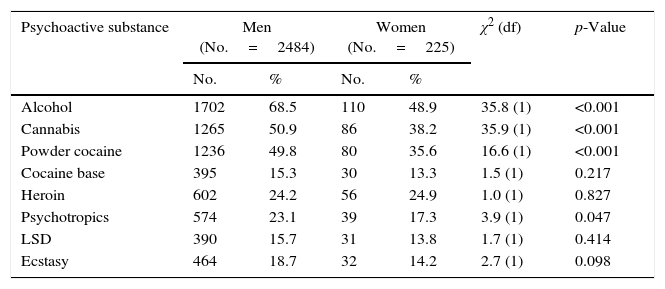

Table 2 shows the prevalence of drug use during the 6 months prior to admission to prison based on sex. The most commonly used legal drug was alcohol for both men and women (68.5% and 48.9%, respectively) and the illegal drug was cannabis (50.9% versus 38.2%). On the other extreme, the use of LSD was the least common for men and women (15.7% versus 14.2%). The use of alcohol, cannabis and powder cocaine in the 6 months prior to prison was clearly higher in the male group than the female group, finding statistically significant associations in all cases (p<0.001).

Prevalence of drug use in the six months prior to entry into prison, according to sex and for the total of the sample.

| Psychoactive substance | Men (No.=2484) | Women (No.=225) | χ2 (df) | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | |||

| Alcohol | 1702 | 68.5 | 110 | 48.9 | 35.8 (1) | <0.001 |

| Cannabis | 1265 | 50.9 | 86 | 38.2 | 35.9 (1) | <0.001 |

| Powder cocaine | 1236 | 49.8 | 80 | 35.6 | 16.6 (1) | <0.001 |

| Cocaine base | 395 | 15.3 | 30 | 13.3 | 1.5 (1) | 0.217 |

| Heroin | 602 | 24.2 | 56 | 24.9 | 1.0 (1) | 0.827 |

| Psychotropics | 574 | 23.1 | 39 | 17.3 | 3.9 (1) | 0.047 |

| LSD | 390 | 15.7 | 31 | 13.8 | 1.7 (1) | 0.414 |

| Ecstasy | 464 | 18.7 | 32 | 14.2 | 2.7 (1) | 0.098 |

df: degrees of freedom.

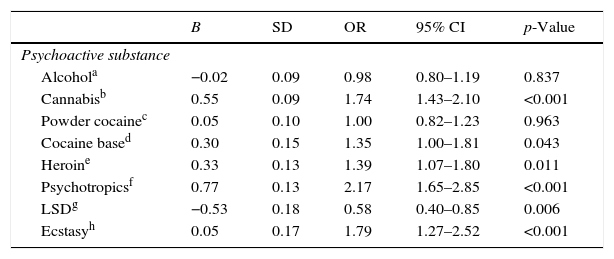

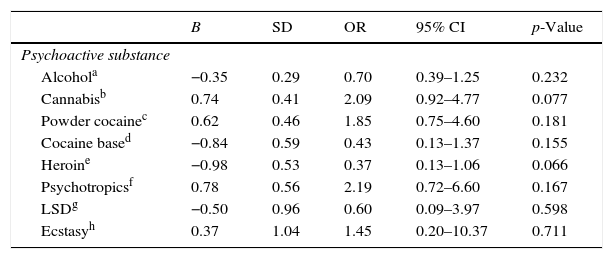

Table 3 shows the results obtained after a logistic regression between each of the psychoactive substances analysed prior to prison and currently receiving treatment (dependent variable) for a mental disorder among the participating men. Inmates who used some of the substances tested (except alcohol and powder cocaine) in the 6 months prior to prison are more likely to be currently receiving mental treatment in prison, with special relevance among users of psychotropic drugs without a medical prescription (OR=2.17, 95% CI: 1.65–2.85; p<0.001) and cannabis (OR: 1.74, 95% CI:1.43–2.10; p<0.001). Finally, Table 4 shows the results generated when carrying out the same statistical analysis between the female group in prison, not finding any statistically significant association.

Logistic regression analysis between drug use in the six months prior to prison and being treated for a mental disorder compared among men (No.=2484).

| B | SD | OR | 95% CI | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Psychoactive substance | |||||

| Alcohola | −0.02 | 0.09 | 0.98 | 0.80–1.19 | 0.837 |

| Cannabisb | 0.55 | 0.09 | 1.74 | 1.43–2.10 | <0.001 |

| Powder cocainec | 0.05 | 0.10 | 1.00 | 0.82–1.23 | 0.963 |

| Cocaine based | 0.30 | 0.15 | 1.35 | 1.00–1.81 | 0.043 |

| Heroine | 0.33 | 0.13 | 1.39 | 1.07–1.80 | 0.011 |

| Psychotropicsf | 0.77 | 0.13 | 2.17 | 1.65–2.85 | <0.001 |

| LSDg | −0.53 | 0.18 | 0.58 | 0.40–0.85 | 0.006 |

| Ecstasyh | 0.05 | 0.17 | 1.79 | 1.27–2.52 | <0.001 |

B: regression coefficient; SD: standard deviation; 95% CI: 95% confidence interval; OR: odds ratio.

Reference category:

Logistic regression analysis between drug use in the six months prior to prison and being treated for a mental disorder compared among women (No.=225).

| B | SD | OR | 95% CI | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Psychoactive substance | |||||

| Alcohola | −0.35 | 0.29 | 0.70 | 0.39–1.25 | 0.232 |

| Cannabisb | 0.74 | 0.41 | 2.09 | 0.92–4.77 | 0.077 |

| Powder cocainec | 0.62 | 0.46 | 1.85 | 0.75–4.60 | 0.181 |

| Cocaine based | −0.84 | 0.59 | 0.43 | 0.13–1.37 | 0.155 |

| Heroine | −0.98 | 0.53 | 0.37 | 0.13–1.06 | 0.066 |

| Psychotropicsf | 0.78 | 0.56 | 2.19 | 0.72–6.60 | 0.167 |

| LSDg | −0.50 | 0.96 | 0.60 | 0.09–3.97 | 0.598 |

| Ecstasyh | 0.37 | 1.04 | 1.45 | 0.20–10.37 | 0.711 |

B: regression coefficient; SD: standard deviation; 95% CI: 95% confidence interval; OR: odds ratio.

Reference category:

The results of this study show, the same as in prior research projects, a high prevalence of pre-prison drug use3–5 and mental disorders during the completion of the custodial sentence,11–14 finding statistically significant associations between both phenomena (pre-prison usage and disorders in prison). Among the drugs analysed, the most commonly consumed before prison for both sexes was alcohol, followed by cannabis and cocaine. These frequencies, the same as in other countries, are significantly higher than the data obtained for use in the general population.21

In a study on drug use in the penitentiary setting in Portugal,22 results were obtained which are very similar to ours, in which it was observed that the use of cannabis and cocaine are the most common for both sexes,4 a preference that is repeated in other investigations.23,24

Regarding the prevalence of mental disorders in the study prisons, the frequencies obtained are sometimes higher8,11 and in other cases similar25 to those shown in other investigations in this same area. The existence of different methodological procedures, especially when defining and measuring the existence of mental disorders, greatly contributes to obtaining different prevalences.26

With regard to a possible existence of dual pathology, the logistic regression analysis shows that for men, except for alcohol, the use of any of the other drugs poses a significant risk, to a greater or lesser extent, of receiving treatment for a mental disorder, with the use of psychotropics, cannabis and ecstasy being those that show greater significance. Although surprisingly this is not so, in the case of women, where none of the associations was statistically significant, contrary to previous research among women in prison.27

Likewise, we have been able to observe how the use of certain drugs, such as psychotropic drugs, cannabis and/or ecstasy, show a strong statistically significant association with the prevalence of a mental disorder in prison. The risk associated with the use of these drugs (especially cannabis) as a trigger for different psychiatric problems has been observed by several previous research studies.28,29 Although surprisingly it is not so in this study for women, where none of the associations were statistically significant. These data are difficult to interpret, Taking into account that the few studies that exist at both the national and international levels have not focused in depth on the influence that alcohol and drug use may have on the development of a mental disorder or vice versa.17–19

This study presents some limitations that may affect the generalisation of its results. First, as they are self-administered questionnaires among the participants themselves and as they deal with delicate aspects, such as the use of alcohol and other drugs prior to prison, the inmates could diminish the veracity in some answers.2 Second, this research has only been conducted in 8 prisons in Spain, so the results obtained cannot be generalised to the prison population as a whole. Third, no information was collected on the possibility of other mental disorders commonly found in penitentiary populations, such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder or psychotic episodes,30 a high percentage of false negatives could have been generated, or false positives in the event that the inmates confused the possibility of a current medical treatment as a mental health treatment. Finally, due to the characteristics related to the study design (cross-sectional analysis) we are only able to determine the association between the analysed variables, without being able to determine if the use of alcohol and other drugs gave origin to the different mental disorders or vice versa.

Finally, the most significant limitation of this research relates to how to measure the prevalence of subjects receiving treatment in prison for a mental disorder. As we have seen, the information on these variables was self-reported by the participants, and this information was not able to be contrasted with the official medical records in order to guarantee the anonymity of the participants. Therefore, it is possible that there were people admitted without having been diagnosed in the penitentiary area. However, previous research has evaluated the obtaining of this type of information using similar collection methods as positive and reliable.12,20 Furthermore, the prevalence of mental disorders observed is similar to that shown by previous research conducted in prisons in Spain, using standardised measures to determine the presence of mental disorders.14,15 Further research is needed using instruments whose validity and reliability has been demonstrated in this type of population in relation to the presence of mental disorders. On the other hand, in the research that is presented and the results and statistically significant associations found, there was no direct relationship when drug use prior to imprisonment and mental disorders during the completion of the sentence was measured. Finally, we must assess the possible bias in the collection of information as a result of the high level of illiteracy (close to 10% according to the General Report31 of the General Secretariat of Penitentiary Institutions) among the penitentiary population and, consequently, their difficulty in participating by completing questionnaires.

In spite of the existing limitations, we must bear in mind that this is the first study conducted in the penitentiary population of Spain where the possible association between histories of consumption of alcohol and other drugs before prison and the presence of different mental disorders is analysed.

We must bear in mind that these data, however, cannot be generalised, that we cannot avoid worrying about the high percentages obtained both in the use of drugs, and mental illness in the penitentiary environment. This makes us reflect on the effectiveness of treatment and prevention programmes, since they appear to be insufficient to try to curb the appearance of these phenomena that clearly affect the health and relationships of individuals, both within and outside of penitentiary institutions. We believe that there should be improvements in the evaluation processes of the programmes, as well as improvements in the detection of needs, which would greatly help the development of future penitentiary policies. Another point to bear in mind is that both prevention programmes and treatments are carried out in an area of deprivation of freedom, which adds an even greater hindrance to the ultimate aim of prison; the rehabilitation and resocialisation of the inmate, since it barely considers the context he or she comes from, collaboration with the family and the work of the inmate.

Conflicts of interestThe author declares that there are no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Caravaca Sánchez F. Consumo de alcohol y drogas como factores asociados a los trastornos mentales entre la población penitenciaria de España. Rev Esp Med Legal. 2017;43:99–105.