To analyse the relationship between the characteristics of the victim, the aggressor and sexual abuse in children and adolescents with the disclosure process; as well as with the chronicity of the event in the Division of the Institute of Legal Medicine of the Junín region-Perú.

Materials and methodsAs a general method of research, the scientific method was applied, carrying out a quantitative study, with a cross-sectional design. All forensic psychological evaluations from January to December of 2017 were analysed, of which only those that fulfilled the selection criteria were selected, leaving a total of 97 cases.

ResultsData from 97 psychological examinations of minors who were victims of sexual abuse were obstructed. Of the victims, 89.7% were female, 99% of the aggressors were male, 47% of the cases of sexual abuse occurred within the family home setting and 5% of victims became pregnant. The highest frequency of recurrent events was when the mother was not living at home (aPR: 1.44; 95%CI: 1.34−1.56; P < .001), living outside the city (aPR: 1, 27; 95%CI: 1.11−1.45; P = .001), late disclosure of abuse (aPR: 2.94; 95%CI: 1.79−4.84; P < .001), and among those who unintentionally revealed the event (aPR: 1.37; 95%CI: 1.06−1.78; P = .001); in contrast, extra-family offenders were less frequent among those with multiple events (aPR: .63, 95%CI: .44−.91, P = .014), adjusted for sex and age.

ConclusionsThe factors associated with recurrent sexual abuse were the victim's relationship with the mother, place of birth of the victim, disclosure latency, circumstance of the disclosure and type of link between victim and aggressor.

Analizar la relación que existe entre las características de la víctima, del agresor y del abuso sexual en niñas, niños y adolescentes con el proceso de revelación; así como, con la cronicidad del evento en la División del Instituto de Medicina Legal de la Región Junín-Perú.

Materiales y métodosDiseño transversal analítico. Se analizaron todas las evaluaciones psicológicas forenses desarrolladas de enero a diciembre del año 2017, de las cuales se seleccionaron sólo aquellas que cumplían con los criterios de selección, quedando un total de 97 casos.

ResultadosEl 90% de las víctimas fueron de sexo femenino, el 99% de los agresores fueron de sexo masculino, 47% de los casos de abuso sexual ocurrieron en un ambiente intradomiciliario familiar y el 5% de las víctimas quedó embarazada. La mayor frecuencia de eventos recurrentes fueron al no tener a la madre viviendo en casa (RPa: 1,44; IC95%: 1,34–1,56; P < 0,001), vivir fuera de la ciudad (RPa: 1,27; IC95%: 1,11–1,45; P = 0,001), el revelar tardíamente el abuso (RPa: 2,94; IC95%: 1,79–4,84; P < 0,001), y entre los que revelaron de manera no intencional (RPa: 1,37; IC95%: 1,06–1,78; P = 0,001); en cambio, los agresores extra familiares fueron menos frecuentes entre los que tuvieron múltiples eventos (RPa: 0,63; IC95%: 0,44–0,91; P = 0,014), ajustados por el sexo y la edad.

ConclusionesLos factores asociados al abuso sexual recurrente fueron: relación de la víctima con la madre, lugar de procedencia de la víctima, latencia de revelación, circunstancia de la revelación y tipo de vínculo de la víctima con el agresor.

Sexual abuse is a phenomenon that is defined as any form of sexual behaviour between two individuals who are in a situation of inequality1; for example, sexual behaviours with minors involves a lack of valid consent2 due to the age difference. It has been said that worldwide approximately 1% of boys, girls or adolescents experience some form of sexual abuse,3 and girls are the most commonly affected.4 The sexual abuse of minors has physical as well as emotional consequences at different levels, at different stages and in different areas of the personal lives of survivors.

Disclosure refers to the process in which the victim describes what occurred in the sexual abuse, and this process may be voluntary or involuntary.5 In judicial procedures it is usual for the two fundamental items of evidence to be the testimony of the minor and the expert reports of medical, psychological and socio-familiar indicators. Nevertheless, often no physical evidence is found, and the acts are usually clandestine,6 so that the disclosure or testimony of the minor is especially important.

Several studies have been performed in connection with the characteristics of the victims of child sexual abuse, the factors which intervene in the disclosure process and recurrence of the event. Girls and female adolescents are the most vulnerable to sexual abuse7–9; nevertheless, in terms of the disclosure of sexual abuse, boys and male adolescents show a higher incidence of unintentional disclosure.10 The absence of the parents and most especially the mother favours the recurrence of sexual abuse during infancy.11 The aggressor is usually a member of the victim’s family, and this in turn hinders early disclosure by the victim.7

Disclosure is the first step in recovery from sexual abuse,12 as to obtain help the victim has to tell a medical professional what happened. Delay in the disclosure of child sexual abuse hinders the successful processing of a case; and as such it also delays the necessary therapeutic intervention.6 This is the reason why it is important to know the factors which are associated with the disclosure process and the recurrence of abuse. Our aim was therefore to analyse the relationship between the characteristics of the victim, those of the aggressor and sexual abuse in girl, boys and adolescents and the disclosure process; as well as the chronicity of the event in the Division of the Legal Medicine Institute of the Junín-Peru Region.

Materials and methodsType of studyThe study design was observational, analytical and transversal.

ParticipantsThe psychological study files of all the boys, girls and adolescents under 18 years of age during 2017 were reviewed, with a single post-interview in the Gesell Dome and with a complete process of forensic psychological evaluation in a Legal Medicine Division of the Junín Region (census sampling). All of the cases which formed part of a legal process due to reports of presumed crimes against sexual freedom made to the Public Ministry were subjected to forensic psychological evaluation. The presumed crimes were acts against modesty, improper touching and rape, and in all of the cases the parents gave their consent for evaluation.

The psychological evaluations of girls, boys and adolescents younger than 18 years were included, as well as those with information corresponding to the single interview in the Gesell Dome. Inconclusive evaluations were excluded, as were those which lacked the necessary data (28 [22.4%] of the forensic psychological evaluations).

MeasurementData were obtained by professional psychologists who are trained in undertaken the single interview and forensic psychological evaluation; all of them had at least 5 years’ experience in the field and with cases of this type. The following information was recorded: personal details (age, sex, education and origin); the description of the abuse in the single interview, the source of information about the characteristics of the abuse, the aggressor, the disclosure process and the chronicity of the abuse. Personal and family history included the characteristics of family structure and the type of relationship of the victim with their parents.

Three basic criteria were applied to the characteristics of the disclosure:

- 1

The context of the disclosure: who the victim selected to reveal the experience of sexual abuse, who may be a member of their family (when the victim reveals the event to one of their parents, a sibling, grandparents, uncles or cousins) or outside the family (when the disclosure is made to a third party, such as a teacher, psychologist, professional, somebody in authority, one of their friends or a friend of their parents).13

- 2

The circumstances of the disclosure: the disclosure may be intentional (when the victim consciously decides to reveal the abusive situation, spontaneously describing what had happened) or it may be unintentional (occurring due to the influence of external circumstances, such as when it is triggered by the questions of close adults, or if third parties discover the abusive event).5

- 3

The latency of the disclosure: this is the time that has passed between the sexual abuse and disclosure of the same.13 The bibliographical review found different ways of categorising this latency, and the two category form was used, known as immediate and late. Disclosure is considered to be immediate if it occurs in the hours or days after the commencement of the aggression, and it is considered to be late if it occurs after 30 days have passed since the start of the sexual abuse.13

The chronicity of sexual abuse refers to the experience of more than one event of the same by the same boy, girl or adolescent; and by the same aggressor.14

ProcedureThis research was approved by the National Directorship of the Legal Medicine Institute, who were informed that the purposes of the same were strictly academic and scientific. It also complied with the ethical criteria which guarantee the confidentiality of the personal data corresponding to the cases reviewed. It was also approved by the Ethics Committee of “San Bartolomé” Hospital Nacional Docente Madre Niño with Exp. No. 15596-19. After this the data were compiled using an Excel format data file, and then they were processed and quality control was applied before exporting the data to the Stata statistical program.

Data analysisThe frequencies and percentages of categorical variables were analysed, as well as the medians and interquartile ranges of the quantitative variables (due to their non-normal behaviour). Statistical analysis was then performed, in which each one of the three outcomes was crossed with the other variables; generalised lineal models were used for this; Poisson family, log link function and robust models.

Results89.7% (n = 97) of all the cases evaluated were female, with a median age of 12 years (interquartile range [IQR]: 8–14 years). Regarding their origin, 73.2% were from the same region as the one where the study took place, and the educational level of the victims was described by 95.9% of them as appropriate for their age. Respecting their family characteristics, the victims reported that only 42.3% of them came from a nuclear family, while in 86.6% of the cases their mother lived in the same home as the victim. Regarding the characteristics of the abuse, a large percentage (66.0%) of the cases occurred within the family context, and 5.2% of the victims became pregnant. Respecting the characteristics of the aggressor, 99.0% of them were men and 47.4% had some form of family tie with the victim, and the majority of the aggressors were over the age of 18 years.

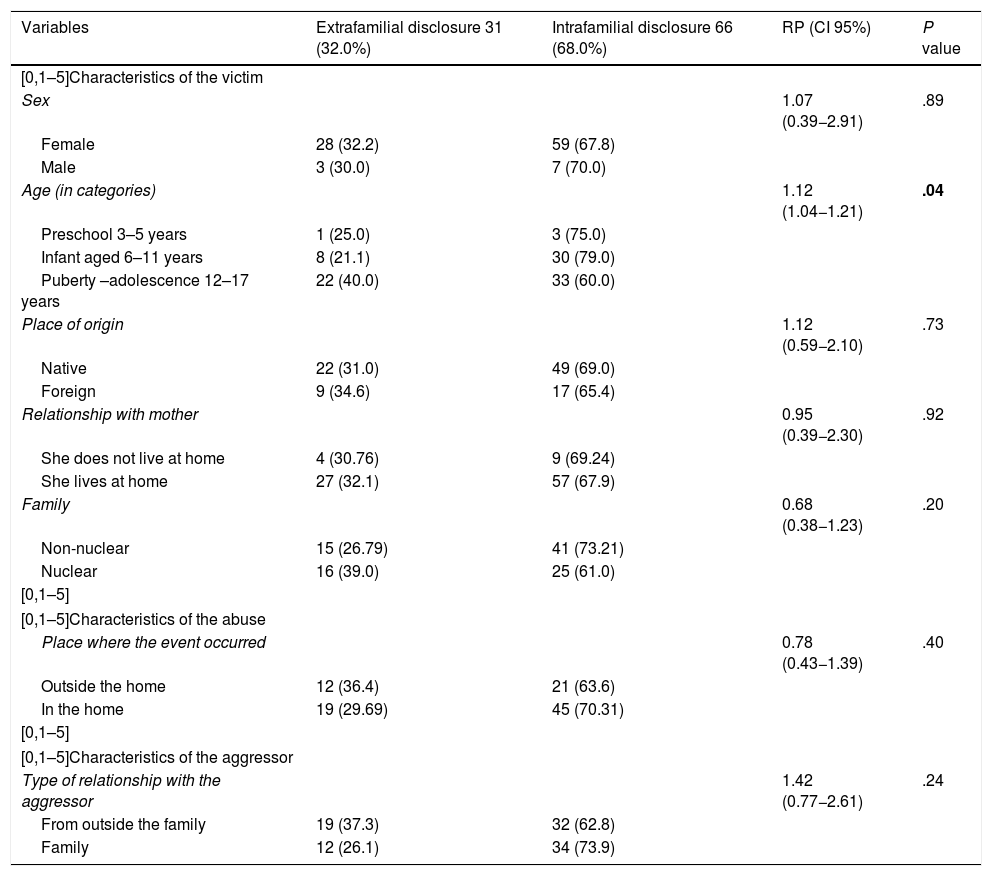

With respect to the disclosure process, it was found that the highest percentage (68.0%) of the victims revealed that they had been abused to someone in their family circle (Table 1).

Bivariate analysis of the characteristics of the victim, the abuse and the aggressor.

| Variables | Extrafamilial disclosure 31 (32.0%) | Intrafamilial disclosure 66 (68.0%) | RP (CI 95%) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [0,1–5]Characteristics of the victim | ||||

| Sex | 1.07 (0.39−2.91) | .89 | ||

| Female | 28 (32.2) | 59 (67.8) | ||

| Male | 3 (30.0) | 7 (70.0) | ||

| Age (in categories) | 1.12 (1.04−1.21) | .04 | ||

| Preschool 3–5 years | 1 (25.0) | 3 (75.0) | ||

| Infant aged 6–11 years | 8 (21.1) | 30 (79.0) | ||

| Puberty –adolescence 12–17 years | 22 (40.0) | 33 (60.0) | ||

| Place of origin | 1.12 (0.59−2.10) | .73 | ||

| Native | 22 (31.0) | 49 (69.0) | ||

| Foreign | 9 (34.6) | 17 (65.4) | ||

| Relationship with mother | 0.95 (0.39−2.30) | .92 | ||

| She does not live at home | 4 (30.76) | 9 (69.24) | ||

| She lives at home | 27 (32.1) | 57 (67.9) | ||

| Family | 0.68 (0.38−1.23) | .20 | ||

| Non-nuclear | 15 (26.79) | 41 (73.21) | ||

| Nuclear | 16 (39.0) | 25 (61.0) | ||

| [0,1–5] | ||||

| [0,1–5]Characteristics of the abuse | ||||

| Place where the event occurred | 0.78 (0.43−1.39) | .40 | ||

| Outside the home | 12 (36.4) | 21 (63.6) | ||

| In the home | 19 (29.69) | 45 (70.31) | ||

| [0,1–5] | ||||

| [0,1–5]Characteristics of the aggressor | ||||

| Type of relationship with the aggressor | 1.42 (0.77−2.61) | .24 | ||

| From outside the family | 19 (37.3) | 32 (62.8) | ||

| Family | 12 (26.1) | 34 (73.9) | ||

The PR (prevalence ratios), CI95% (95% confidence intervals) and P values were obtained with generalised lineal models, with the Poisson family, the log link function and robust models.

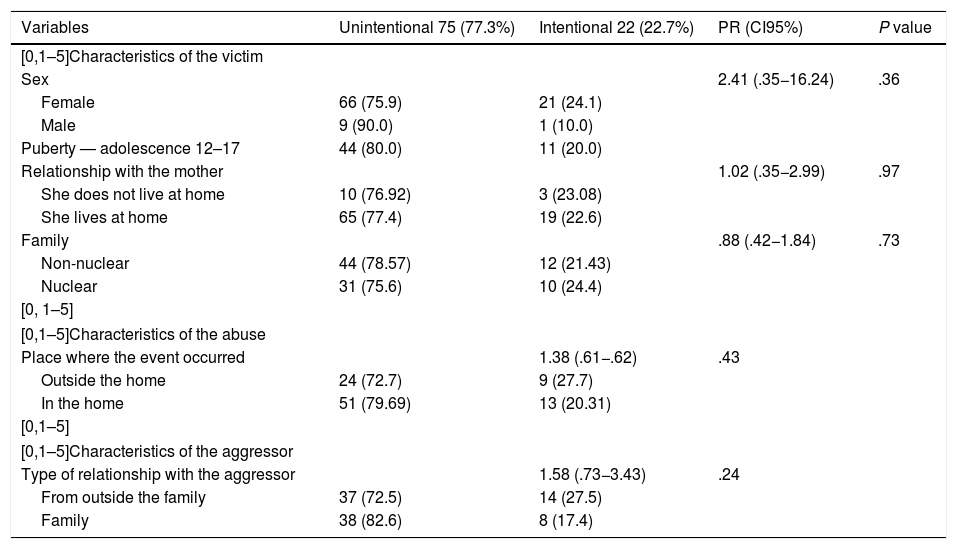

In connection with the circumstances of the disclosure, this was found to occur unintentionally in the majority of occasions (77.3%). Bivariate analysis of the characteristics of the victim, the abuse and the aggressor together with the circumstances of the disclosure was not found to be statistically significant. An outstanding finding was that the majority of male victims (90%) disclosed the abuse unintentionally (Table 2).

Bivariate analysis of the characteristics of the victim, the abuse and the aggressor, with the circumstances of disclosure (unintentional and intentional disclosure).

| Variables | Unintentional 75 (77.3%) | Intentional 22 (22.7%) | PR (CI95%) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [0,1–5]Characteristics of the victim | ||||

| Sex | 2.41 (.35−16.24) | .36 | ||

| Female | 66 (75.9) | 21 (24.1) | ||

| Male | 9 (90.0) | 1 (10.0) | ||

| Puberty — adolescence 12–17 | 44 (80.0) | 11 (20.0) | ||

| Relationship with the mother | 1.02 (.35−2.99) | .97 | ||

| She does not live at home | 10 (76.92) | 3 (23.08) | ||

| She lives at home | 65 (77.4) | 19 (22.6) | ||

| Family | .88 (.42−1.84) | .73 | ||

| Non-nuclear | 44 (78.57) | 12 (21.43) | ||

| Nuclear | 31 (75.6) | 10 (24.4) | ||

| [0, 1–5] | ||||

| [0,1–5]Characteristics of the abuse | ||||

| Place where the event occurred | 1.38 (.61−.62) | .43 | ||

| Outside the home | 24 (72.7) | 9 (27.7) | ||

| In the home | 51 (79.69) | 13 (20.31) | ||

| [0,1–5] | ||||

| [0,1–5]Characteristics of the aggressor | ||||

| Type of relationship with the aggressor | 1.58 (.73−3.43) | .24 | ||

| From outside the family | 37 (72.5) | 14 (27.5) | ||

| Family | 38 (82.6) | 8 (17.4) | ||

The PR (prevalence ratios), CI95% (95% confidence intervals) and P values were obtained with generalised lineal models, with the Poisson family, the log link function and robust models.

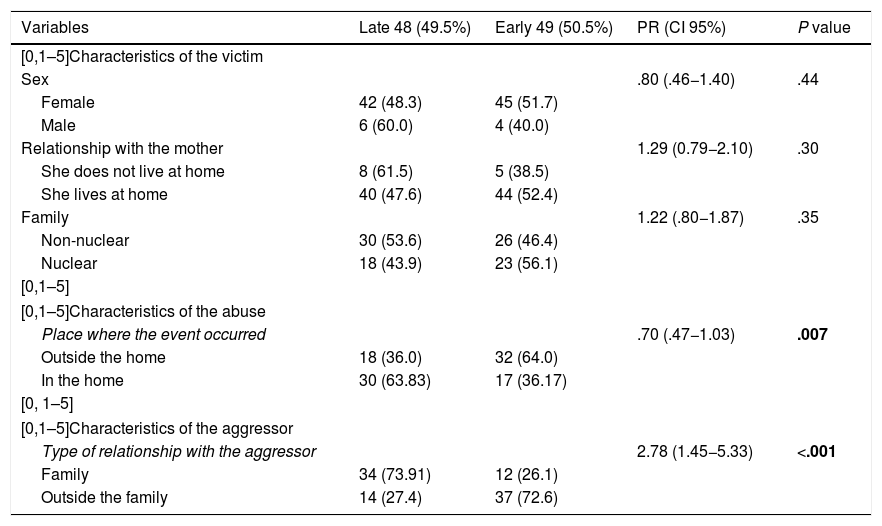

Regarding the delay before the abuse was revealed, almost half of the abuses were disclosed late (49.5%). When the latency time for disclosure of the abuse was analysed it was found that when it occurred in a context outside the home, it was disclosed early in the majority of cases (72.7%), while abuse in the home was disclosed late. Likewise, a significant relationship was found between the latency time before disclosure and the type of relationship between the aggressor and the victim, and late disclosure occurred in 73.9% of cases when the aggressor belonged to the family circle (Table 3).

Bivariate analysis of the characteristics of the victim, the abuse and the aggressor, with the latency time before disclosure.

| Variables | Late 48 (49.5%) | Early 49 (50.5%) | PR (CI 95%) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [0,1–5]Characteristics of the victim | ||||

| Sex | .80 (.46−1.40) | .44 | ||

| Female | 42 (48.3) | 45 (51.7) | ||

| Male | 6 (60.0) | 4 (40.0) | ||

| Relationship with the mother | 1.29 (0.79−2.10) | .30 | ||

| She does not live at home | 8 (61.5) | 5 (38.5) | ||

| She lives at home | 40 (47.6) | 44 (52.4) | ||

| Family | 1.22 (.80−1.87) | .35 | ||

| Non-nuclear | 30 (53.6) | 26 (46.4) | ||

| Nuclear | 18 (43.9) | 23 (56.1) | ||

| [0,1–5] | ||||

| [0,1–5]Characteristics of the abuse | ||||

| Place where the event occurred | .70 (.47−1.03) | .007 | ||

| Outside the home | 18 (36.0) | 32 (64.0) | ||

| In the home | 30 (63.83) | 17 (36.17) | ||

| [0, 1–5] | ||||

| [0,1–5]Characteristics of the aggressor | ||||

| Type of relationship with the aggressor | 2.78 (1.45−5.33) | <.001 | ||

| Family | 34 (73.91) | 12 (26.1) | ||

| Outside the family | 14 (27.4) | 37 (72.6) | ||

The PR (prevalence ratios), CI95% (95% confidence intervals) and P values were obtained with generalised lineal models, with the Poisson family, the log link function and robust models.

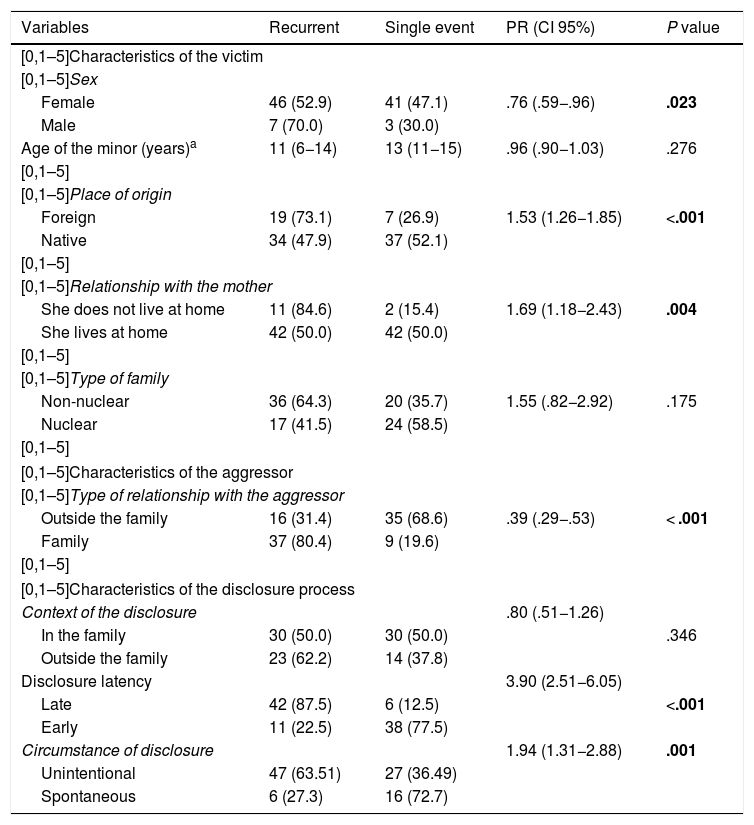

In connection with the chronicity of sexual abuse, bivariate analysis found that recurring events were less frequent with female victims and those in which the aggressor had a non-family relationship with the victim. The victims who originated in a place other than the one where the evaluation took place and who did not live with their mother suffered a higher frequency of recurring events; this was also the case for those who disclosed the abuse late and unintentionally, as they too suffered a higher frequency of recurring events (Table 4).

Bivariate analysis of the characteristics of the victim, the aggressor and the disclosure process with the chronicity of the sexual abuse.

| Variables | Recurrent | Single event | PR (CI 95%) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [0,1–5]Characteristics of the victim | ||||

| [0,1–5]Sex | ||||

| Female | 46 (52.9) | 41 (47.1) | .76 (.59−.96) | .023 |

| Male | 7 (70.0) | 3 (30.0) | ||

| Age of the minor (years)a | 11 (6−14) | 13 (11−15) | .96 (.90−1.03) | .276 |

| [0,1–5] | ||||

| [0,1–5]Place of origin | ||||

| Foreign | 19 (73.1) | 7 (26.9) | 1.53 (1.26−1.85) | <.001 |

| Native | 34 (47.9) | 37 (52.1) | ||

| [0,1–5] | ||||

| [0,1–5]Relationship with the mother | ||||

| She does not live at home | 11 (84.6) | 2 (15.4) | 1.69 (1.18−2.43) | .004 |

| She lives at home | 42 (50.0) | 42 (50.0) | ||

| [0,1–5] | ||||

| [0,1–5]Type of family | ||||

| Non-nuclear | 36 (64.3) | 20 (35.7) | 1.55 (.82−2.92) | .175 |

| Nuclear | 17 (41.5) | 24 (58.5) | ||

| [0,1–5] | ||||

| [0,1–5]Characteristics of the aggressor | ||||

| [0,1–5]Type of relationship with the aggressor | ||||

| Outside the family | 16 (31.4) | 35 (68.6) | .39 (.29−.53) | < .001 |

| Family | 37 (80.4) | 9 (19.6) | ||

| [0,1–5] | ||||

| [0,1–5]Characteristics of the disclosure process | ||||

| Context of the disclosure | .80 (.51−1.26) | |||

| In the family | 30 (50.0) | 30 (50.0) | .346 | |

| Outside the family | 23 (62.2) | 14 (37.8) | ||

| Disclosure latency | 3.90 (2.51−6.05) | |||

| Late | 42 (87.5) | 6 (12.5) | <.001 | |

| Early | 11 (22.5) | 38 (77.5) | ||

| Circumstance of disclosure | 1.94 (1.31−2.88) | .001 | ||

| Unintentional | 47 (63.51) | 27 (36.49) | ||

| Spontaneous | 6 (27.3) | 16 (72.7) | ||

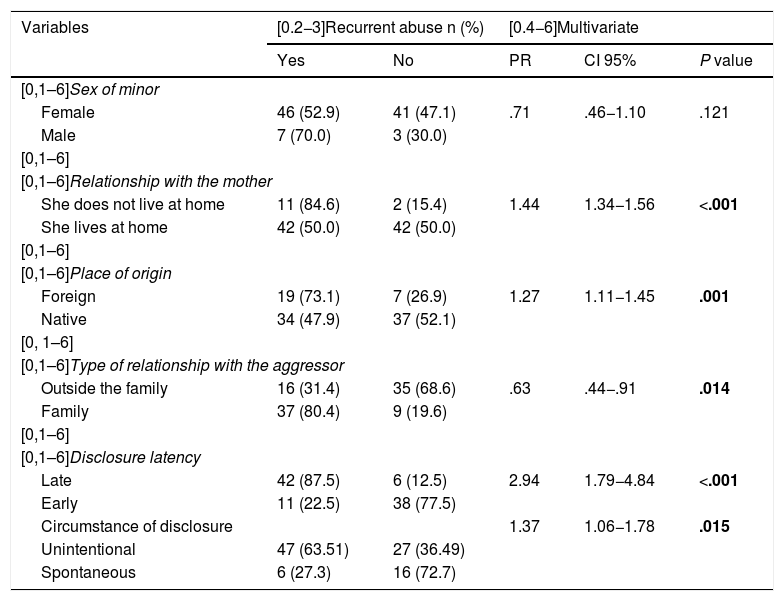

Multivariate analysis found a higher frequency of recurring events among the minors who did not live in the same home as their mother (RPa: 1.44; CI95%: 1.34−1.56; P< .001), among those who lived outside Huancayo (RPa: 1.27; CI95%: 1.11−1.45; P = .001), among those who disclosed the abuse late (RPa: 2.94; CI95%: 1.79−4.84; P< .001), and among those who disclosed it unintentionally (RPa: 1.37; CI95%: 1.06−1.78; P = .001). On the other hand, those who suffered multiple events were less likely to have an aggressor from outside the family (RPa: .63; CI95%: .44−.91; P = .014). These crosses were adjusted for sex and the age category of the minors involved (Table 5).

Multivariate analysis of the factors associated with recurrent sexual abuse.

| Variables | [0.2−3]Recurrent abuse n (%) | [0.4−6]Multivariate | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | PR | CI 95% | P value | |

| [0,1–6]Sex of minor | |||||

| Female | 46 (52.9) | 41 (47.1) | .71 | .46−1.10 | .121 |

| Male | 7 (70.0) | 3 (30.0) | |||

| [0,1–6] | |||||

| [0,1–6]Relationship with the mother | |||||

| She does not live at home | 11 (84.6) | 2 (15.4) | 1.44 | 1.34−1.56 | <.001 |

| She lives at home | 42 (50.0) | 42 (50.0) | |||

| [0,1–6] | |||||

| [0,1–6]Place of origin | |||||

| Foreign | 19 (73.1) | 7 (26.9) | 1.27 | 1.11−1.45 | .001 |

| Native | 34 (47.9) | 37 (52.1) | |||

| [0, 1–6] | |||||

| [0,1–6]Type of relationship with the aggressor | |||||

| Outside the family | 16 (31.4) | 35 (68.6) | .63 | .44−.91 | .014 |

| Family | 37 (80.4) | 9 (19.6) | |||

| [0,1–6] | |||||

| [0,1–6]Disclosure latency | |||||

| Late | 42 (87.5) | 6 (12.5) | 2.94 | 1.79−4.84 | <.001 |

| Early | 11 (22.5) | 38 (77.5) | |||

| Circumstance of disclosure | 1.37 | 1.06−1.78 | .015 | ||

| Unintentional | 47 (63.51) | 27 (36.49) | |||

| Spontaneous | 6 (27.3) | 16 (72.7) | |||

The PR (prevalence ratios), CI95% (95% confidence intervals) and P values were obtained with generalised lineal models, with the Poisson family, the log link function, robust models and victim age category adjustment.

Nine of every ten sexual abuse victims were female, showing that women are more vulnerable to sexual aggression. Moreover, in connection with the percentage of sexual abuse victims who are women, data were found that indicate that this percentage rises as they approach adolescence and youth. In Hong Kong (China) one study concluded that 96% of the victims of sexual abuse were women.7 Two studies in the U.S.A. show slightly lower but no less important figures.8,9 Cultural differences around the world do not change this tendency, so that being a woman means being more vulnerable to sexual aggression.

More than two thirds of all sexual abuse victims are younger than 18 years.9 In our study the median age of the victims was 12 years (IQR 8–14), and similar results were found in a study on child sex abuse in Hong Kong (China).7 In another study performed in the U.S.A., the age range when the majority of cases occurred (81%) was from 12 to 17 years.8 The risk of suffering violent rape also increased dramatically from 10 to 14 years of age.9 The above considerations lead us to infer that the increase in the risk of suffering sexual abuse occurs at the start of puberty, and that it is associated with the development of secondary sexual characteristics which are evident in female adolescents.

Characteristics of the place where aggression took placeIn respect of the context in which the sexual abuse took place, more than half of these events occurred in a family setting; a retrospective study of university students in the U.S.A, showed that the majority of child victims of sexual aggression knew their aggressor.15 The presence of the aggressor in the family allows them to have access to minors and groom them sexually and manipulate them, so that it will not be necessary for them to use physical force and with the aim of preventing the minors from revealing the abuse; additionally, in an intrafamily context the minor’s carers would find their disclosure less likely to be truthful.16

Characteristics of the aggressorAlmost all of the aggressors were men; this datum is similar to the results of other studies undertaken in China and the U.S.A., in which more than 95% of the aggressors were men.7,8 From a social point-of-view we can state that gender inequalities still favour the practice of abusive sexual behaviours due to the dominant position of men vs women; this is aggravated when generational factors come into play, as infancy is a state of physical, psychological and sexual fragility.

Characteristics of the disclosure processDisclosure of sexual abuse is the first step in a successful process of personal emotional recovery, to gain social and familial support and to access the legal system. Nevertheless, in our study more than half of the cases were disclosed late and unintentionally. A similar result was reported in another study, where 58% of the victims waited more than one year before revealing their experience of sexual abuse.17 However, in a study of 263 sexually abused adolescents it was found that the highest percentage (43%) disclosed it immediately.18 We also found a study of boys and girls in Israel which found that 57% of them intentionally disclosed the abuse.19 These differences may be due to the fact that the study was undertaken in a country that has no legal support for an Integrated Sexual Education program20; so that boys, girls and adolescents lack the skills to express themselves spontaneously about their sexuality. Moreover, some negative sexual experiences favour non-disclosure (such as fear, blame and shame), leading to the imposition of a culture of secrecy.

The majority of male victims (90%) were found to make unintentional disclosures. A study in Chile reported that males disclose the aggression due to questioning (49% of males versus 34% of females).10 In the same way, in Quebec, Canada, girls and women were found to be far more likely to report abuse than were men or boys.21,22 Additionally, the males reported that they were not ready to disclose abut because they feared being labelled as homosexuals or victims.23,24

When abuse has occurred outside the home it is usually disclosed at an early stage, and likewise disclosure tends to take place late when the aggressor is part of the family circle. These results are similar to those of a Chinese study, which found that when the aggressor belongs to the family circle, the abuse was discovered much later.7 In the same way, in Israel the researchers found that boys who knew their aggressors were less likely to reveal tell their parents about the abuse (28%) that were those whose aggressors were strangers (67%; P: .027).19,25 Similarly, a study in Italy reported that the impediments against disclosure included factors such as shame and the fear of causing problems in the family.26

Characteristics of chronicity and its associated factorsSexual abuse may create emotional affects and sequelae, as was shown in a Colombian study which stated that repeated sexual abuse may cause mental disorders such as depression, suicide, self-harm, poor self-esteem and all types of addiction. It may also lead to prostitution, relationship problems, aversion to sexual contact and abortions.27 Among the factors associated with repeated abuse, we found that it occurred more often when children were not living with their mother. These results are similar to those found in a study in which children had no maternal support, who were up to five times more likely to suffer recurring events of sexual abuse.28 Parental ties are the most important predictive factor for disclosure by boys as well as girls.11 The emotional tie between parents and their children increases the communication between them in all areas, including that of sexuality; this tie is strengthened when parents live with their children, and it facilitates disclosure by the latter, thereby preventing sexual aggressions from repeating.

In connection with place of origin, this study describes a higher frequency of multiple events among victims who live outside the city of Huancayo. These results may be due to the greater difficulty in accessing health services in areas distant from the city, together with the lack of sex education and the poor standard of care for children there. A higher frequency of multiple events was also found among those cases in which disclosure was late. This is similar to other results which indicate that when sexual aggression is chronic, the majority of cases (93%) are disclosed late.10 Respecting the emotional consequences, children expressed fear or shame more often when the abuse was recurring.19 These results may allow us to take preventive measures, as early disclosure may reduce the chronicity of these experiences and their associated consequences.29

This study had the limitation of selection bias, as data were only gathered from one group of children and adolescents, so that the results cannot be extrapolated to a larger population. Nevertheless, this is the first scientific report in a Peruvian mountain city, so that it may be used as a basis by the corresponding authorities and other researchers to continue investigating this subject. Prospective studies could be initiated, as well as ones which cover other variables that could not be studied here due to the type of its design.

We conclude that there is an inverse relationship between the sexual behaviour of the victim and the aggressor. The number of victims who disclosed sexual abuse late is alarming, and this occurred prior to commencing the legal process; more than half of the victims suffered chronic sexual abuse. Suffering sexual abuse in the home when the aggressor is a member of your family is devastating, but it is still more probable than becoming the victim of sexual abuse by a stranger. The disclosure of sexual abuse by a minor makes it possible to activate the legal system; however, given that a forensic medical examination is rarely able to confirm and never able to rule out child sex abuse, a forensic psychological interview with the victim is of maximum importance, as it gives details of the victim, the aggressor, the abuse, the disclosure and the chronicity of the event.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

To the girls, boys and adolescents who survived sexual abuse, for their strength in disclosing this and commencing on their road to recovery, to the people who accompany them in this process and the professionals who expertly conducted the forensic psychological interviews. Thanks also to the National Directorship of the Legal Medicine and Forensic Sciences Institute of Peru for their confidence and support for carrying out this study.

Please cite this article as: Lívano RM, Valdivia-Lívano S, Mejia CR. Evaluaciones psicológicas forenses de abuso sexual en menores: proceso de revelación y cronicidad del evento en la serranía peruana. Rev Esp Med Legal. 2021;47:57–65.