To evaluate the association between IL-6 in prostatic tissue/blood sample and BPH-LUTS, so as to preliminarily discover an indicator of inflammation that could show the severity of LUTS.

Patients and methodsThe prostatic tissues and blood samples were collected from 56 patients who underwent transurethral plasmakinetic resection of the prostate (TUPKRP). The association between IL-6 detected on prostatic tissues/blood sample and LUTS parameters, including international prostate symptom score (IPSS), peak flow rate (Qmax) and urodynamic parameters were analyzed with SPSS version 18.0, and p-value <0.05 was chosen as the criterion for statistical significance.

ResultsThe TPSA and prostate volume (PV) were found to be higher in the inflammation group (p=0.021, 0.036). There was a positive association between prostate tissue inflammation and LUTS ([IPSS, storage symptoms score (SSS), voiding symptoms score (VSS), p<0.05], [Qmax, p=0.025], [obstruction, p=0.027] and [AUR, p=0.018]). The level of serum IL-6 was significantly higher in inflammatory group (p=0.008). However, no differences were observed in different degrees of inflammation (p=0.393). The level of IL-6 in prostatic tissue significantly increased with the degree of inflammation (p<0.001), and the intensity of IL-6 expression was statistically correlative with the degree of inflammation (p<0.001). The IL-6 expression in prostatic tissue was statistically relevant with IPSS (p=0.018) and SSS (p=0.012).

ConclusionIL-6 expression in prostatic tissue is associated with storage IPSS, suggesting chronic inflammation might contribute to storage LUTS.

Evaluar la relación entre il-6 y bph-lut en muestras de tejido prostático/sangre, con el fin de identificar indicadores de inflamación que reflejen la gravedad de los lut.

Pacientes y métodosSe recolectaron muestras de tejido prostático y sangre de 56 pacientes sometidos a una plasmatectomía transuretral prostática. Se aplicó la versión 18.0 de SPSS para analizar la correlación entre el il-6 de tejido prostático/muestra de sangre y los parámetros relacionados con los LUTS (puntuación internacional de síntomas prostáticos (IPSS), flujo máximo (Qmax), parámetros urodinámicos), con UN valor p<0,05 como criterio para una diferencia estadísticamente significativa.

ResultadosHubo diferencias estadísticamente significativas (p=0,021, 0,036) entre el grupo con inflamación y el grupo sin inflamación en TPSA y PV. La inflamación del tejido prostático se relacionó positivamente con LUTS ([IPSS, puntuación de síntomas de almacenamiento (SSS), puntuación de síntomas de micción (VSS), p<0,001), y la intensidad de la expresión de il-6 se correlacionó estadísticamente con el grado de inflamación (p<0,001). La expresión de il-6 en el tejido prostático fue estadísticamente significativa con IPSS (p=0,018) y SSS (p=0,012).

ConclusionesLa expresión de il-6 en el tejido prostático está relacionada con el almacenamiento de IPSS, lo que sugiere que la inflamación crónica puede estar involucrada en el almacenamiento de LUTS.

Lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) was defined as three categories including storage, voiding and post-micturition symptoms, of which storage symptoms (51%) were more common than voiding symptoms (26%).1,2 BPH is a dominant cause of LUTS in the male over the age of 60 years. The REDUCE trial shows that the chronic inflammation in prostate tissue can be detected in 77.6% of patients with BPH who underwent prostate biopsies, and many studies have shown a significant correlation between chronic prostatic inflammation and LUTS severity, prostate volume and increased risk of acute urinary retention.3–5

Evidence from MTOPS and REDUCE clinical studies revealed that risk for LUTS due to BPH is correlated with intra-prostatic infiltration of inflammatory cells.6,7 Inflammatory cells (T and B lymphocytes, macrophages and mast cells) may contribute to the pathogenesis and progression of BPH by activating cytokines release and driving local growth factor production in the prostatic tissue. The pro-inflammatory cytokines have been widely reported in prostatic tissues of patients with BPH.8,9 Therefore, cytokine (IL-6, IL-8) has been proposed as a link between chronic prostate inflammation and the development of BPH. Interleukin-6 (IL-6) is a pro-inflammatory cytokine, which plays a crucial role in the regulation of T-cell differentiation and B-cell progression to antibody-producing plasma cells.10 The association between IL-6 and BPH-LUTS has not been reported before. Our study aims to evaluate the correlation between IL-6 in prostatic tissue/serum sample and BPH-LUTS, so as to preliminarily discover an indicator of inflammation that showed the severity of LUTS.

Material and methodsPatient selectionFrom January 2017 to December 2018, 133 patients who underwent transurethral plasmakinetic resection of the prostate (TUPKRP) for LUTS were diagnosed histologically as benign prostatic hyperplasia at Baotou Central Hospital affiliated to Inner Mongolia Medical University, but only 56 patients agreed to collect sample for further study. Before the TUPKRP, digital rectal examination (DRE) and transrectal ultrasonography were used to access the prostate volume for all patients. Serum PSA were obtained using screening test.

Exclusion criteria of patients: (1) urinary tract infection (white cell count in the urine >3/HP), (2) connective tissue diseases, (3) neurologic diseases, (4) hematological malignancy history, and (5) medical therapy (e.g. chemotherapy or immunotherapy) which may influence the level of peripheral blood parameters.

Sample collectionA prospective study was performed with full approval of the ethics committee of the Baotou Central Hospital affiliated to Inner Mongolia Medical University (No. YKD2017016). After patient consent was obtained, the prostate tissues were collected from 56 patients who underwent TUPKRP. 3ml of serum was separated from 56 participant's blood samples during operation, and then stored at −20°C for measurements of IL-6 by ELISA.

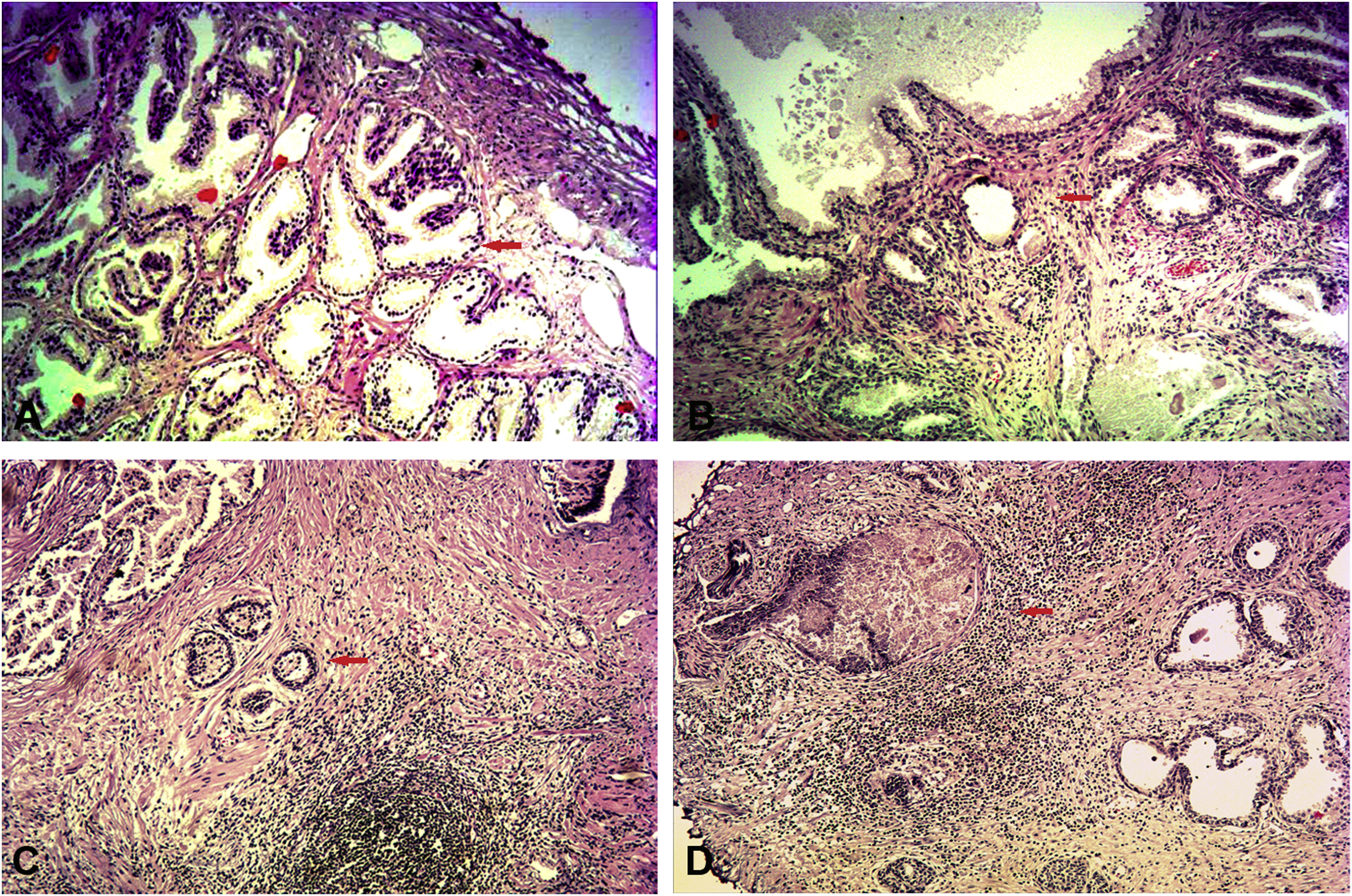

Inflammation assessmentThe assessment of prostate tissue inflammation was supported in a blinded manner by a certified pathologist according to the International Histopathological Classification System of Prostatic Inflammation (mild: scattered inflammatory cell infiltration within the stroma without lymphoid nodules; moderate: nonconfluent lymphoid nodules; severe: large inflammatory areas with confluence of infiltrates) (Fig. 1). The prostate specimens obtained from TURP and were stained by hematoxylin and eosin (H&E).

The assessment of prostate tissue inflammation via H&E staining (100×). (A) Non-inflammatory BPH; normal prostate gland (red arrow). (B) Mild-inflammatory BPH; scattered distribution of lymphocytes around the gland (red arrow). (C) Moderate-inflammatory BPH; nonconfluent lymphoid nodules (red arrow). (D) Severe-inflammatory BPH; large inflammatory areas with confluence of infiltrates (red arrow).

The objective clinical parameters of LUTS were collected from the urodynamic. The peak flow rate (Qmax) was measured by uroflowmetry at a voided volume of >150ml. The extent of bladder outlet obstruction (BOO) was evaluated by pressure-flow studies (PFS) according to the Schafer line.

The subjective clinical parameters of LUTS, including international prostate symptom score (IPSS), storage symptoms score (SSS), voiding symptoms score (VSS), and QOL were collected from the medical records before TURP to evaluate lower urinary tract symptoms.

ImmunohistochemistryParaffin wax embedded formaldehyde-fixed tissues were cut to 5μm sections. Each section was de-waxed in xylene and rehydrated in dilutions of ethanol; 3% H2O2 and phosphate buffer saline (PBS) were used to deactivate the endogenous peroxidase. Antigen retrieval was obtained by 0.25% trypsin at indoor temperature for 20min. The slides were washed with PBS 3 times. Serial sections were incubated with goat serum anti-IL6 for 30min at indoor temperature. Then serial sections were incubated with anti-human IL-6 primary antibody overnight at 4°C. The secondary anti-human IL-6 antibody was incubated at indoor temperature for 60min, and then the tissue sections followed by PBS washing in 3 times for 5min each. The tissue sections were incubated with diaminabenzidine (DAB) substrate for 5min. The samples were photographed using optical microscope. The scores of tissue staining were evaluated by 3 pathologists who performed independent reviews of all samples.

Immunohistochemical evaluation: The tissue of staining intensity (no staining=0, weak staining=1, moderate staining=2, strong staining=3), and staining extent (% of positive cells; <5%=0, 5–25%=1, 26–50%=2, 51–75%=3, and >75%=4). The scale=staining intensity+staining extent; scale ≤3: −; scale=4: +; scale=5: ++; scale=≥6: +++.

Enzyme-linked immune sorbent assayConcentrations of IL-6 in serums were measured using commercially available enzyme-linked immunoassay (ELISA) kits (Uscnlife, Wuhan, China) according to the instructions. The minimum detectable value was 1.0pg/ml. All samples were assayed in duplicate.

Statistical analysisCategorical variables were described by frequencies and percentages. Continuous variables are presented as mean±standard deviation of the mean. Statistical comparisons between the subgroups were tested using chi-square tests for categorical characteristics, and the Mann–Whitney U tests were used for continuous characteristics. The serum IL-6 level in different inflammatory groups was compared with one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Correlations between IL-6 level and BPH/LUTS parameters were analyzed by Pearson correlation coefficient in case of continuous characteristics and Spearman correlation coefficient in case of categorical characteristics. All analyses were performed by the SPSS ver18.0, and statistical significance was defined as p<0.05.

ResultsAccording to the International Histopathological Classification System of Prostatic Inflammation, 133 patients were divided into inflammation group and non-inflammation group. The clinical characteristics of patients were summarized in Table 1. The median age and BMI have no significance between two groups (p-value: 0.407, 0.142). The TPSA and prostate volume (PV) showed a statistically significance between two groups (p=0.010, 0.046), and the TPSA and PV were found to be higher in the inflammation group than those without inflammation (8.84±8.41 vs 5.41±4.24, 81.69±42.26 vs 61.52±33.99). There was a positive association between prostate tissue inflammation and LUTS (IPSS, SSS, VSS, QOL [p<0.01], Qmax [p=0.025], obstruction [p=0.009] and AUR [p=0.038]).

Comparison of BPH/LUTS parameters between the inflammatory and non-inflammatory BPH group.

| Group | BPH/AIP | BPH alone | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. of patients | 107 | 26 | |

| Median (IQR) | |||

| Age, years | 71.53±6.50 | 70.35±6.46 | 0.407 |

| TPSA, ng/ml | 8.84±8.41 | 5.41±4.24 | 0.010 |

| Prostate volume, cm3 | 81.69±42.26 | 61.52±33.99 | 0.046 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 25.51±2.46 | 25.83±2.16 | 0.142 |

| IPSS | 23.29±4.06 | 18.38±4.63 | 0.000 |

| SSS | 12.06±2.13 | 10.00±2.06 | 0.000 |

| VSS | 9.79±1.84 | 7.50±3.40 | 0.000 |

| QOL | 4.11±0.98 | 3.23±1.07 | 0.000 |

| Qmax | 5.14±2.89 | 6.91±3.90 | 0.025 |

| N(%) | |||

| Obstruction classification | 0.009 | ||

| III | 44 | 19 | |

| IV | 27 | 5 | |

| V | 22 | 2 | |

| VI | 14 | 0 | |

| AUR | 0.038 | ||

| Absent | 38 | 15 | |

| Present | 69 | 11 |

AIP: asymptomatic inflammatory prostatitis; BMI: body mass index.

In 56 patients who have agreed to be collected sample, the level of serum IL-6 was significantly higher in inflammatory group (319.93±90.76 vs 214.13±29.20, p=0.008). However, no differences were observed in different degrees of inflammation (299.94±113.69 vs 304.55±71.81 vs 348.64±91.57, p=0.393). (Fig. 2).

The comparison of serum cytokine in different degrees of inflammatory group. (A) Serum IL-6 level between inflammatory and non-inflammatory group; (B) serum IL-6 in different degrees of inflammation (*p<0.01; mild-inflammation [n=15]; moderate-inflammation [n=20]; severe-inflammation [n=12]; non-inflammation [n=9]).

As Table 2 shows, the highest correlation was only found between serum IL-6 level and Qmax (r=0.430, p=0.007). However, serum IL-6 level was not significantly associated with IPSS (r=−0.089, p=0.595), VSS (r=−0.073, p=0.665), SSS (r=−0.121, p=0.470), QOL (r=0.004, p=0.983), obstruction classification (r=0.052, p=0.754) and AUR (r=0.052, p=0.755).

The expression of IL-6 in prostatic tissues was detected by immunohistochemistry. The results showed that IL-6 was mainly expressed in glandular epithelium (Fig. 3). Table 3 summarizes the expression level of IL-6 significantly increased with the degree of inflammation (χ2=15.579, p<0.001), and the intensity of IL-6 expression was statistically correlative with the degree of inflammation (rs=0.526, p<0.001).

The correlation between IL-6 expression in prostatic tissues and BPH/LUTS parameters was seen in Fig. 4. The IL-6 expression was statistically associated with IPSS (r=0.315; p=0.018) and SSS (r=0.333; p=0.012). The IL-6 expression was no associated with VSS (r=0.186, p=0.171), QOL (r=0.197, p=0.146), obstruction classification (r=0.133, p=0.327) and Qmax (r=−0.076, p=0.575).

DiscussionHistological inflammation is commonly found in BPH specimens, and it affects the biological characteristics of benign prostate hyperplasia, such as patient symptoms, PSA levels and prostate volume. The REDUCE trail7 showed an association between the degree of chronic inflammation and LUTS related to BPH. Among 8224 men, 77.6% had chronic inflammation, and only 21.6% had no inflammation. For those men with chronic inflammation, 89% had mild, 10.7% had moderate and 0.3% had severe inflammation. In addition, the results of this trail showed that total IPSS and subscores were higher in patients with histological chronic inflammation at baseline compared with those with no chronic inflammation. After the longitudinal evaluation for 4 years, Nickel et al.3 confirmed that chronic inflammation is associated with severity and the progression of LUTS related to BPH, and chronic inflammation at baseline was associated with an increased risk of acute urinary retention. In the Robert's study,11 the results reveal the strong correlation between histological inflammation, prostate volume and IPSS. In this study, the prostatic inflammation was diagnosed by histopathology in 47/56 patients. Of the 83.9% who had prostate inflammation, 31.9% had mild, 42.6% had moderate and 25.5% had severe inflammation. Because our study was conducted in BPH patients with severe symptoms requiring surgical treatment, these limitations may result in the difference with the REDUCE trail. However, our study still suggested that local prostatic histological inflammation is positively associated with prostate volume, initial PSA and LUTS (IPSS, SSS, VSS, QOL, Qmax, obstruction and AUR). Above all, we assume that prostatic inflammation may have a major impact on LUTS and may be a trigger of LUTS.

The International Histopathological Classification System of Prostatic Inflammation was established in according to the infiltration of inflammatory cells (T and B lymphocytes, macrophages and mast cells). However, once activated inflammatory has been attracted to prostatic tissue, they may then secrete a number of pro-inflammatory cytokines that could directly contribute to prostate growth. IL-6 is a pro-inflammatory cytokine, which plays a key role in the progression and pathogenesis of BPH by regulating the T-cell differentiation and B-cell progression to antibody-producing plasma cells.10,12 IL-6 has been found expressed also in BPH stromal and epithelial cells, while the IL-6R receptor was detected on stromal and epithelial.13–15. Engelhardt et al.16 found IL-6 expression was higher in patients with asymptomatic inflammatory prostatitis than in those without prostatitis. Jiang17 further demonstrated IL-6 expression in prostatic tissue was significantly increased in inflammatory BPH group and was much higher in the severe-inflammatory group. In our study, the results found the expression of IL-6 significantly increased with the degree of inflammation, and the intensity of IL-6 expression was statistically relevant with the degree of inflammation, suggesting the IL-6 could reflect the inflammatory condition of BPH. LUTS can result from a complex interplay of pathophysiologic features that include bladder dysfunction and bladder outlet dysfunction. Inamura et al.18 reported that the location of inflammation in the prostate might be an important factor affecting the severity of LUTS, especially voiding dysfunction. However, our study revealed the IL-6 expression in prostatic tissue was positively relevant with IPSS and storage symptoms score and negatively associated with voiding symptoms score, suggesting chronic inflammation affects the bladder storage function that consequently causes higher storage LUTS. Funahashi et al.19 reported the mechanism that prostatic inflammation contributes to the overactive bladder symptoms. Voiding LUTS is not completely attributed to the chronic inflammation in the prostate tissue, and the enlarged prostate glands are the most dominant portion to cause BOO and voiding LUTS. Hence, it is not difficulty to understand why alpha-blocker could improve voiding LUTS but have limited effect on storage LUTS.

Many studies revealed the correlation between the serum cytokines and prostatic chronic inflammation.9,20,21 Similarly, our study also showed the serum IL-6 level was statistically significance between inflammatory and non-inflammatory group. In addition, no differences of the serum IL-6 level were observed in different degrees of inflammation. Cytokine, such as IL-6, IL-8 and CRP, mediates numerous inflammatory and immunomodulatory pathways.22 Unlike other cytokines with restricted cellular expression, almost every stromal and immune cells in the human body can produce IL-6, IL-8 and CRP.23 Therefore, the level of serum IL-6, IL-8 and CRP was unstable, which was susceptible to systematic conditions (i.e. stress). There was a controversy about the correlation between serum level of serum cytokines and LUTS. The Boston Area Community Health (BACH) survey24 emphasized the association between male nocturia and straining and serum CRP, but the results in the cohort study in Olmsted County25 did not observe the association between serum CRP and the increase of obstructive LUTS. Meanwhile, Hung et al.26 found serum CRP levels are associated with storage LUTS. Wu et al.27 reported a positive correlation between the level of serum IL-6 and the AUR in elderly Chinese patients with BPH. The same situation emerged in our study. Nothing but “Qmax” was found to have the strongest correlation with serum IL-6 level, however, the IL-6 expression in prostatic tissue was relevant with storage symptoms and not associated with “Qmax”. IL-6 is synthesized in a local lesion in the initial stage if inflammation and then it moves to the liver through the bloodstream, followed by the rapid induction of an extensive range of acute phase proteins such as CRP, serum amyloid A and fibrinogen.28 Above all, it is difficult to assess the chronic prostatic inflammation status and the severity of LUTS by measuring serum IL-6 level.

The limitation of our study as follows: Firstly, the sample size is small. Tissues and serum from a total of 56 patients were obtained and examined to analyze the expression level of IL-6 in prostatic tissue. Due to consent of the patients, we were not able to perform more sample assays, which limited the sample number in our experiment. Secondly, although we exclude the patients with infection, hematological malignancy history, neurologic diseases, connective tissue diseases or medical therapy, systematic elements (i.e. stress) could not be avoided completely, which may affect the results of serum cytokine level. Thirdly, there are some limits to the pathologist visual scoring. Larger studies and the standardization of IHC staining for IL-6 are required to determine IL-6 expression in prostate tissue.

ConclusionOur study posed an essential clinical implication that IL-6 expression in prostatic tissue is associated with storage IPSS, suggesting chronic inflammation might play a role in the patients with storage LUTS. It is difficult to assess the chronic prostatic inflammation status and the severity of LUTS by measuring serum IL-6 level.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this study.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work center on the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained the written informed consent of the patients or subjects mentioned in the article. The corresponding author is in possession of this document.

Conflict of interestThis research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. No conflict of interest to declare.

![The comparison of serum cytokine in different degrees of inflammatory group. (A) Serum IL-6 level between inflammatory and non-inflammatory group; (B) serum IL-6 in different degrees of inflammation (*p<0.01; mild-inflammation [n=15]; moderate-inflammation [n=20]; severe-inflammation [n=12]; non-inflammation [n=9]). The comparison of serum cytokine in different degrees of inflammatory group. (A) Serum IL-6 level between inflammatory and non-inflammatory group; (B) serum IL-6 in different degrees of inflammation (*p<0.01; mild-inflammation [n=15]; moderate-inflammation [n=20]; severe-inflammation [n=12]; non-inflammation [n=9]).](https://static.elsevier.es/multimedia/1698031X/0000002100000002/v2_202304071800/S1698031X22000826/v2_202304071800/en/main.assets/thumbnail/gr2.jpeg?xkr=ue/ImdikoIMrsJoerZ+w96p5LBcBpyJTqfwgorxm+Ow=)