After the negative effects of smoking on public health were proven, smoking cessation campaigns were initiated by health ministries and non-governmental organizations. Many drugs have been tried to reduce the addiction to smoking and the nicotine contained in it. Recently, e-cigarettes (EC) are widely used for smoking cessation efforts, although the effects and possible harms are not fully known. In our study, we planned to show the effect of cigarette and EC smoke on the male urogenital system.

MethodsAdult male wistar rats were exposed to cigarette and EC smoke in a specially designed glass bell jar. Urine cotinine levels, testicular weights, gonadosomatic index, sperm count and sperm motility, testicular histology, and biochemical findings were compared with the control group.

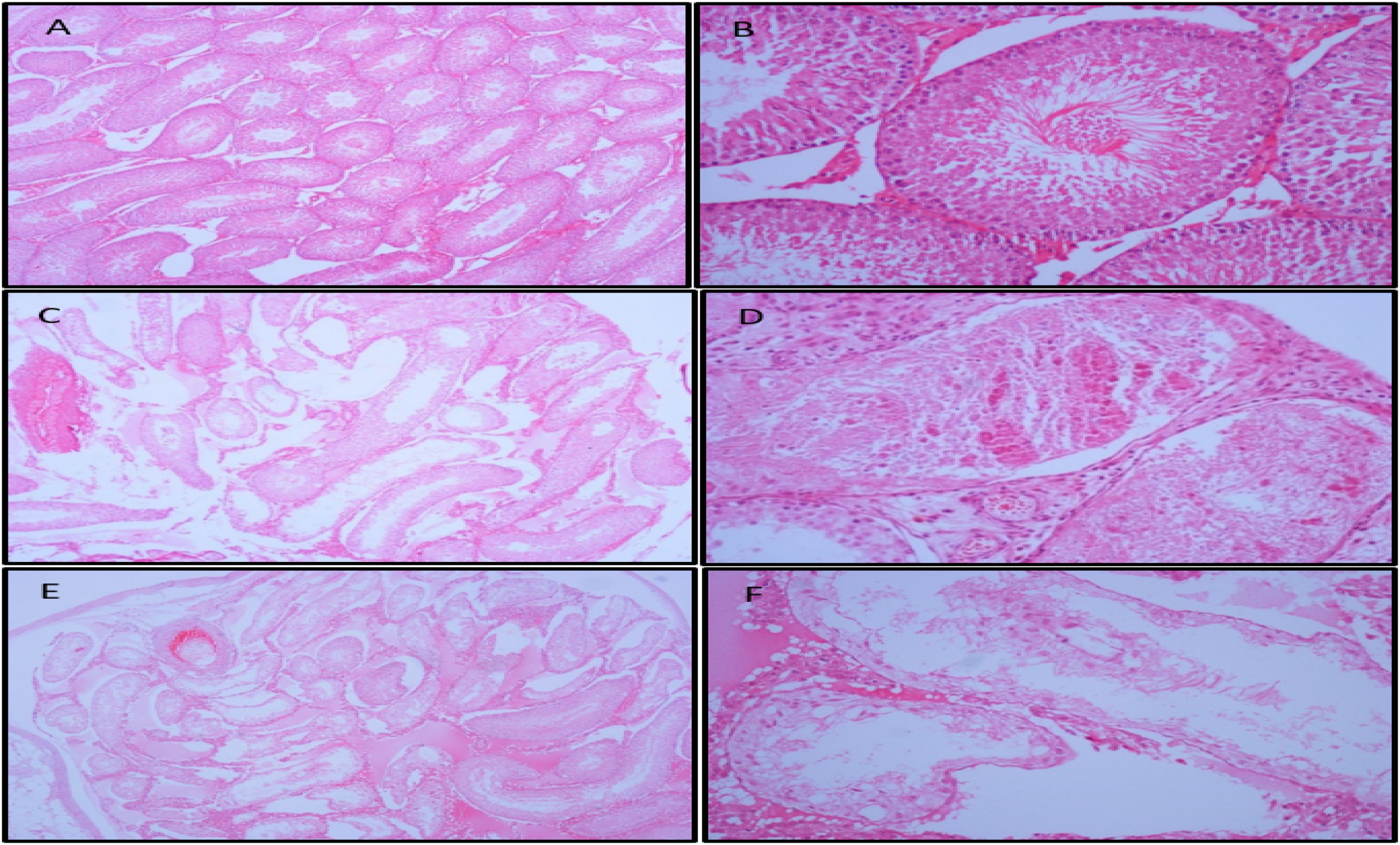

ResultsIn some rats in the cigarette and EC group, the seminiferous tubules were disorganized, and the germ cells and Sertoli cells were separated and shed. Stopped germ cell separation, cavity formation, necrosis, fibrosis, and atrophy were observed in severe cases. Higher PCO levels were found in the cigarette group compared to controls. Tissue homogenates levels of LPO were higher in both EC and cigarette groups compared to controls. No significant differences were observed between groups in terms of sperm motility and sperm count.

ConclusionCigarette and EC liquid can increase oxidative stress as well as cause morphological changes in the testicle. To be a safe option in smoking cessation studies, its effect on people needs to be enlightened.

Una vez demostrados los efectos negativos del tabaquismo sobre la salud pública, los ministerios de salud y las ONG iniciaron campañas contra el consumo de tabaco. Hasta la fecha se han empleado múltiples fármacos en diferentes intentos por reducir la adicción al tabaco y el contenido de nicotina. Recientemente, el uso de cigarrillos electrónicos (CE) ha experimentado una amplia difusión como método para dejar de fumar, si bien sus efectos y posibles daños todavía no se conocen por completo. El objetivo de este estudio es determinar los efectos de cigarrillos y de CE sobre el sistema urogenital masculino.

MétodosSe expusieron ejemplares masculinos adultos de rata Wistar al humo de cigarrillos y de CE en una campana de cristal especialmente diseñada para dicha prueba. Se compararon niveles de nicotina en orina, peso testicular, índice gonadosomático, recuento y movilidad de espermatozoides, histología testicular y variables bioquímicas con los de un grupo de control.

ResultadosEn algunas ratas del grupo de cigarrillo y de CE los túbulos seminíferos presentaban desorganización y las células germinales y de Sertoli mostraban separación y desprendimiento. En casos graves se apreció separación detenida de células germinales, formación de cavidades, necrosis, fibrosis y atrofia. En el grupo de cigarrillo se encontraron niveles más altos de PCO en relación con los individuos del grupo control. Los niveles de homogenato de tejido de LPO fueron más elevados tanto en los grupos de CE como de cigarrillos, en comparación con el grupo de control. No se observan diferencias significativas entre grupos en cuanto al recuento y la movilidad de espermatozoides.

ConclusioónLos cigarrillos y los líquidos de CE pueden aumentar el estrés oxidativo, así como provocar cambios morfológicos en los testículos. Para considerar el CE como una opción segura para combatir el tabaquismo se requieren estudios complementarios con el fin de evidenciar sus efectos sobre los seres humanos.

An average of 1.3 billion people use tobacco products with a consequent death rate of more than 8 million people each year worldwide 1. The rate of addiction to smoking in men aged>15 years is 30%, and this rate rises to 46% in men of reproductive age. 2,3. Serious health problems, including cancer and cardiovascular disease have been related to smoking, and decreased fertility 4. The American Society of Reproductive Medicine has emphasized the potential negative effects of tobacco consumption on conception, semen parameters, and the success of assisted reproductive technology (ART) 5. Different molecular mechanisms have been reported to be related to decreased fertility including chromatin damage and increased oxidative stress.6–8

Oxidative stress, which causes intracellular molecule damage or cell death, is defined as the imbalance between reactive oxygen species (ROS) and antioxidants. With different degrees of importance, oxidative stress can be responsible for several diseases such as cancer, diabetes, metabolic disorders, atherosclerosis, and cardiovascular problems 9.

Oxidative stress is defined as the disruption of the oxidant/antioxidant balance. Free radicals are part of human metabolism and the oxidant/antioxidant balance is a significant mechanism of homeostasis 10. Polyunsaturated fatty acids, thiol groups, and DNA can be subjected to oxidative damage due to excess reactive oxygen species 11. Previous studies have reported various biomarkers including Glutathione peroxidase (GPX4), protein carbonyl (PCO), superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT), glucose 6 phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) and lipid peroxidase (LPO) have been evaluated to show biochemical changes related to oxidative stress 12.

Electronic cigarettes (EC) are devices that deliver nicotine to the user in a carrier aerosol system. EC has been developed as a safer alternative to smoking and aid to reducing smoking addiction. EC use has increased exponentially in the last few years. EC marketing expenditure in the US increased 30-fold in less than 5 years between 2010 and 2014. According to 2015 data, 3.7% of adults were reported to regularly use EC and the highest rate of use was between the ages of 18–24 years 13. Although it is accepted that EC has fewer negative effects on health than smoking, EC vapor may lead to excessive production of ROS, DNA damage, carcinogenic effects increasing inflammatory blood cells in airways, and lipid peroxidation in the lungs 14. The United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported that as of January 14, 2020, there were 2668 EVALI cases reported in the USA 15.

Even though there are many studies of the effect of smoking on male fertility, the number of studies investigating the effect of EC on male fertility is quite limited. Therefore, the aim of this study was to investigate the effects of EC aerosol on sperm count, testicular histology, and oxidative stress markers in blood and testicular tissue. The hypothesis of this study was that EC use might lead to decreased fertility, related to increased oxidative stress. This study provides an exciting opportunity to advance current knowledge regarding the effect of smoking and EC on the male genital system pathogenesis.

MethodsCigarette, EC, and EC liquidWinston brand cigarettes containing 4mg tar, 0.4mg nicotine, and 4mg carbon monoxide were used for the cigarette exposure group. Joyetech eGo Aio 1500 mAh was used as an EC device, with 0.6mg/ml nicotine in a 55/45 ratio of propylene glycol and vegetable glycerin as the liquid mixture. The liquid mixture did not contain any aroma or flavoring agents.

Exposure to animalsTo evaluate the effects of EC on male fertility, twenty four adult male Wistar rats were separated into three experimental groups. One group was treated with traditional cigarette smoking and one group with EC smoking. During exposure, all rats in the cigarette and EC groups were exposed to 1.2mg/h of nicotine. The third group, as the control group received no intervention. At the end of the experiment, euthanasia was applied to all the rats in each group. Detailed descriptions of the experimental procedures are given below. Approval for the study was granted by the Cumhuriyet University Local Animal Research Ethics Committee (Decision No. 65202830-050.04.04-76).

The male Wistar rats were kept in conditions of a 12-h light/dark cycle (light between 6.00am and 6.00pm) at a temperature of 22–24°C and 55% humidity. All procedures were carried out according to the guidelines outlined in the National Institute of Health's Guide to the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Group 1 (n: 8): The control group received no intervention, and the animals were only exposed to room air during the 8th week.

Group 2 (n: 8): In a specially designed glass bell jar, these rats were exposed to 3 cigarettes in 1 hour twice a day during the 8th week. CO and CO2 levels were measured regularly during exposure (sup mat).

Group 3 (n: 8): In a specially designed glass bell jar, these rats were exposed to EC as 2ml of EC liquid consumed in 1h twice a day during the 8th week.

In the 4th week, urine samples were taken from all the rats, for the examination of urine cotinine level, which is a predominant metabolite of nicotine. Since urine cotinine is a reliable biomarker of nicotine exposure 16, the urine cotinine levels were measured in all the groups to evaluate the effects of the procedures.

End of the experimentAt the end of the experiment, all the rats were anesthetized using an intramuscular injection of 15mg/kg Xylazine and 90mg/kg and Ketamine hydrochloride. Then for euthanasia, sodium pentobarbital was administered intraperitoneally at the dose of 10mg/100g body weight. Before the euthanasia procedure, blood samples were taken by heart puncture into red top tubes (Becton Dickinson, UK). After centrifugation at 3500rpm for 15minutes at 4°C, the serum was separated and immediately frozen at −80°C (Wisecryo, Korea). Bilateral testicles were removed and weighed to determine the gonadosomatic index (GSI).

SpermiogramSperm samples were rapidly milked from bilateral epididymis and vas deferens. The sperm samples were quickly transferred into the Krebs–Ringer bicarbonate medium at 37°C. Sperm counts and motilities were measured using the Neubauer hemocytometer, as described by Anderson et al.17

HistopathologyThe left-side testes were stored under suitable conditions for tissue homogenization, and the right-side testes were placed in 10% formalin solution and fixed for 24h for histopathological examination.

Macroscopic sections taken from the tissues were embedded in paraffin blocks. Sections 3 microns in thickness were cut with a microtome (Leica) and stained with hematoxylin–eosin (Facepath).

Histopathological examination was performed under a Leica light microscope at ×40 and 200 magnifications. Morphologically, germinal epithelial irregularity was evaluated as mild to moderate changes according to the degree of cellular desquamation. Seminiferous tubular atrophy, necrosis, fibrosis, and a decrease in spermatid and germinal epithelium were evaluated as severe changes.

Preparation of tissue homogenate and isolation of subcellular organellesThe tissue was thawed, weighed, and then homogenized in ice-cold 10mL/g phosphate saline buffer (PBS) (0.01M, ph:7.4). Tissue samples of 0.5g were weighed for analysis. The homogenates were then centrifuged for 5min at 5000g, and the supernatant was kept at −80°C until analysis. The testis homogenate samples were thawed and filtered, then centrifuged at 2000rpm for 15min at 4°C to precipitate nuclei and other cellular debris. The supernatant fluids were centrifuged at 10,000 (rpm) for 20min at 4°C to separate mitochondrial pellet, which was washed three times with ice-cold phosphate buffer (0.01M, ph:7.4) at 12,000rpm for 5min at 4°C. Biochemical analyses were performed immediately after isolation.

Biochemical analysesQuantitative ELISA kits were used to detect GPX4 (Cayman Chemical, Michigan 48108, USA), PCO (Sunred Bio, China), SOD (Cayman Chemical, Michigan, USA), CAT (Cayman Chemical, Michigan, USA), G6PD (Cayman Chemical, Michigan, USA) and LPO (MyBioSource, San Diego, USA) concentrations in plasma and tissue samples.

ResultsUrine cotinine levelsIn the fourth week of the experiment, evaluations were made of the urine cotinine levels of the control group, the group exposed to cigarette smoke and the group exposed to EC vapor. The urine cotinine levels in the cigarette and EC groups were found to be significantly higher than those of the control group (Table 1).

Testicular weights, gonadosomatic index, sperm count, and sperm motilityRelative testicular weights were calculated using following formula;

No statistically significant differences were observed in the cigarette and EC groups compared to the control group. The GSI levels were found to be higher in the control group than in the cigarette group (Table 2). No statistical differences were observed between the EC and control groups. No significant differences were observed between the groups in terms of sperm motility and sperm count. Box plots for testicular weights, gonadosomatic index, sperm count, and sperm motility are shown in Table 2.

Comparison of testicular weight, GSI, Sperm count and Sperm motility between groups.

| Parameters | Cigarette | E-cigarette | Control | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Testicular weight (g) | 1.22±0.16a | 1.51±0.18b | 1.35±0.14a,b | =0.012 |

| Gonadosomatic index | 0.33±0.05b | 0.39±0.06a,b | 0.40±0.04a | =0.03 |

| Sperm count (×106/ml) | 86.9±11.2 | 95.1±8.8 | 98.5±7.6 | =0.066 |

| Sperm motility (%) | 65.3±8.9 | 68.6±7.9 | 66.3±8.8 | =0.738 |

Results are given as mean±standard deviation. p<0.05 was accepted as statistically significant difference. Different superscripts represent a statistically significant difference between groups on the same row.

The histological structure of the testes was analyzed in all the groups. No pathological changes were detected in the control group in the microscopic examination. Regular placement of germ cells and Sertoli cells in the seminiferous tubules of the testis was observed. Spermatids at different stages of spermatogenesis were present in the lumen and the lumen was narrowed. No atrophic tubule was seen. In the EC group, severe changes were observed in one case, mild changes were observed in four cases, and normal histological findings were observed in three cases. In the smoking group, severe changes were observed in two cases (Fig. 1), moderate changes in one case, mild changes in one case, and normal histological findings were observed in four cases. In all cases with changes, the seminiferous tubules were disorganized and the germ cells and Sertoli cells were separated and shed. Halted germ cell separation, cavity formation, necrosis, fibrosis, and atrophy were observed in severe cases.

Biochemical findingsHigher PCO levels were found in the cigarette group compared to the control group. Tissue homogenates levels of LPO were higher in both the EC and cigarette groups compared to the control group. The comparisons between the groups of testis homogenates GPX4, PCO, SOD, CAT, G6PD, and LPO concentrations are shown in Table 3. Box plots for GPX4, PCO, SOD, CAT, G6PD, and LPO are shown in Table 3.

Comparison of testis homogenates GPX4, PCO, SOD, CAT, G6PD and LPO concentrations between groups.

| Testis Homogenates | Group 1 (Cigarette group) | Group 2 (E-cigarette group) | Group 3 (Control) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GPX4 (ng/mL) | 3.94±2.05 | 3.28±1.33 | 3.98±1.95 | =0.690 |

| PCO (pg/mL) | 222.4±89.17a | 128.1±74.07a,b | 99.44±73.68b | =0.018 |

| SOD (pg/mL) | 30.49±9.12 | 31.92±17.93 | 17.80±10.12 | =0.074 |

| CAT (U/mL) | 36.87±0.1 | 34.98±12.49 | 41.03±1.53 | =0.400 |

| G6PDH (nmol/min/mL) | 3.30±1.14 | 1.63±1.09 | 2.08±1.39 | =0.078 |

| LPO (ng/mL) | 46.29±11.66a | 42.03±7.14a | 13.46±4.37b | <0.001 |

GPX4: glutathione peroxidase 4, PCO: protein carbonyl, SOD: superoxide dismutase, CAT: catalase, G6PD: glucose 6 phosphate dehydrogenase, LPO: lipid peroxidase. Results are expressed as mean±standard deviation with 95% confidence intervals. Different superscripts represent a statistically significant difference between groups on the same row.

Conformity of the data to normal distribution was assessed with both the Shapiro–Wilks and D’Agostino Pearson normality tests. The Kruskal–Wallis test was used to compare the differences in terms of GPX4, PCO, SOD, CAT, G6PD, and LPO for between-group comparisons. Dunn's multiple comparisons test was used for multiple comparison. A value of p<0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses of the data were carried out with Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS/PC 16.0) for Windows software (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA).

DiscussionThe results of this study demonstrated that GSI levels were significantly higher in the control group than in the smoking group, with no statistically significant difference between the EC and control groups. Severe changes were observed in one case in the EC group and in the cigarette group and slight changes in the remaining rats (particularly thinning of the germinal epithelium in the seminiferous tubules, cavitation, and signs of desquamation, necrosis, and atrophy in the germinal epithelium). In the smoking group, the changes were seen to be more severe (thinning of the germinal epithelium, cavitation and excessive thinning of the germinal epithelium, fibrosis and atrophy findings) in a larger number of rats. Lipoxygenase levels increased in both exposure groups compared to the control group, and this was higher in the smoking group. Higher PCO levels were found in the cigarette group compared to the control group. Sperm count and motility were evaluated with no statistically significant difference found in either parameter. This study is one of the few studies in literature to have compared the effects of cigarette smoke and EC liquid using aerosol.

The urine cotinine level in the smoking group increased compared to the control group. Testicular weight and gonadosomatic index were found to be lower in the smoking group compared to the control group. Although the sperm count decreased compared to the control group, no statistically significant difference was found. PCO and LPO levels were found to be higher in testicular homogenate compared to the control group. In the histomorphological examination of the smoking group, various levels of seminiferous tubular atrophy, necrosis, fibrosis, spermatid and germinal epithelial reduction were observed. In a study by La Maestra et al., the testes and body weight of rats exposed to cigarettes were observed to have decreased compared to the control group. In the histomorphological examination, there was determined to be degeneration and atrophy of the tubules, loss of spermatogenesis, a decrease in the spermatogenic cell layer and a significant decrease in the number of Leydig cells and epididymal spermatozoa and anomalies in these cells 18. In another study, Muhammed M. et al. showed that lipid peroxidation and the end product TBARS were significantly increased 19. The result of chronic cigarette smoke exposure appears to be testicular tissue damage and abnormal spermatogenesis.

In the current study, while there was no significant difference between the testicular weights of the groups, GSI was seen to be lower in the cigarette and EC groups. In a study by Vivarelli et al., it was observed that testicular weight and GSI were lower in the EC group compared to the control group 20. This can be explained by the fact that the weight gain of the rats in the cigarette and EC groups was not correlated with the increase in testicular weight and the testicular development in the experimental group was relatively slow.

In the current study histopathological evaluation of the testicles of rats exposed to cigarette and EC smoke, it was observed that seminiferous tubules were disorganized, and germ cells and Sertoli cells were decomposed and shed, especially in the group exposed to cigarette smoke. In severe cases, halted germ cell detachment, cavity formation, necrosis, fibrosis, and atrophy were observed. Similarly, El Golli et al. applied EC liquid intraperitoneally and showed disorganization in seminiferous tubular content and desquamation in germ cells and decreased sperm density in the EC group 21. The current study findings in the smoking group were similar to the findings reported by Omotoso et al. in a similar study. The findings of that study were intercellular degeneration and disintegration, a decreased number of spermatogenic cells, decreased number of mature and high-quality sperms, and a slight decrease in Leydig cell count 22. In another study with a similar design to the current research, Wawryk-Gawda et al. investigated the histological effects of cigarette smoke and EC vapor on rat testicles 23. Consistent with the current study findings, it was suggested that although cigarette smoke causes more severe histological changes, EC vapor also has negative effects on testicular histology and may lead to male infertility. This could be due to the negative effects on testicular histology of nicotine in EC vapor, as well as the effect of other toxic chemicals.

After exposure to cigarette smoke, PCO residue was observed in the testicular homogenate. The LPO level was found to be higher in both experimental groups compared to the control group. In a study by Yoshimura et al. of the pathological specimens of patients with human testicular cancer, it was shown that the level of lipoxygenase increased significantly compared to the control group and it was concluded that it is an enzyme necessary for the growth of tumor cells 24. In the examination of testicular homogenate, lipoxygenase levels were found to be significantly higher in the cigarette and EC groups compared to the control group. No evidence of testicular tumor was found in the histopathological examination of the rat testes. However, it was seen that an existing tumor tissue can grow more rapidly with the increase of lipoxygenase level after exposure to cigarette and EC smoke. More studies are needed to reveal this relationship. Colombo et al. investigated the effects of cigarette smoke on bronchial epithelial cells, and reported that cigarette smoke increases protein carbonylation in a dose-dependent manner, and carbonylated proteins are involved in primary metabolic processes such as protein, lipid metabolism, and energy production as well as basic cellular processes such as cell cycle and chromosome separation. In the current study, protein carbonylation was observed to have increased in the smoking group. Increased protein carbonylation indicates that smoking can cause significant changes in testicular cells.

Sperm count and motility were evaluated in this study and no statistically significant difference was found in either parameter. Although there were no statistical differences in respect of the sperm count, the values of the control and EC groups were similar, and lower in the smoking group. In contrast, Golli et al. reported that EC liquid containing nicotine and without nicotine significantly reduced sperm count 21, whereas another study reported changes in semen parameters similar to those of the current study 22. This difference could be due to the application of the normal form of exposure to EC liquid via inhalation in the current study and intraperitoneal injection in the previously mentioned study. Despite all these findings, the reasons for the lack of a significant change in semen parameters and especially motility is attributed to the active role of many mechanisms and pathways during spermatogenesis, and many studies are still being conducted on this subject. Of the limited number of studies on this subject, the distinguishing feature of the current study is that the EC liquid was applied directly by vaporization and inhalation with the normal physiological mechanism.

ConclusionThe results of this study showed changes in testicular histopathology, spermiogram, and oxidative stress parameters of rats exposed to cigarette and EC smoke. Therefore, it should be considered that although EC liquid has been introduced as harmless in smoking cessation studies, it could increase oxidative stress and cause morphological changes in the testicle. Nevertheless, more research is needed to understand the post-exposure spermiogram results.

LimitationsSome limitations of this study must be considered. Although the EC smoke was used in aerosol form, there was no biochemical analysis of the EC liquid. Biochemical analysis of the e-liquid may be required to evaluate the results more accurately.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that the procedures followed were in accordance with the regulations of the relevant clinical research ethics committee and with those of the Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki).

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

StatementsOur article has not been submitted anywhere.

Financial disclosureSivas Cumhuriyet University Scientific Research Projects study support was received with the project numbered T-786.

Conflict of interestThe authors declared no conflict of interest.