Down syndrome (DS) is the most frequent aneuploidy in the humans. Children with DS have a predisposition to obesity, and it is known that the phenotype of these individuals may lead to a bias in the use of the World Health Organization body mass index (WHO BMI).

ObjectivesThis study proposes the assessment of body composition in individuals with DS using the dual X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) technique, the current gold standard for comparison of its values with those found in general population.

MethodData was collected randomly from patients, such as their BMI and body composition with the DXA machine Lunar Prodigy Advance®, with their values compared to literature references and statistically analyzed with their WHO BMI z-score.

Results45 individuals were analyzed, with a prevalence of 58% of girls, mean age of 11 years old and 35.5% were obese by WHO BMI z-score; 57.1% of the subgroup of eutrophic individuals with DS by WHO BMI had altered body composition values.

ConclusionThe WHO BMI z-score in patients with DS has a correspondence with the body composition only in individuals classified as overweight or obese by BMI z-score. It was concluded that BMI is not an appropriate tool to infer the body composition in children with DS.

El síndrome de Down (SD) es la aneuploidía más frecuente en la especie humana. Los niños con SD tienen predisposición a la obesidad, y bien es sabido que el fenotipo de estos individuos puede llevar a un sesgo en el uso del índice de masa corporal (IMC) de la Organización Mundial de la Salud (OMS).

ObjetivosEste estudio propone valorar la composición corporal en individuos con SD utilizando la técnica de densitometría (DXA), el patrón de referencia actual para comparar estos valores con los propios de la población general.

MétodoSe recolectaron aleatoriamente los datos de los pacientes, tales como IMC y composición corporal valorada mediante DXA (Lunar Prodigy Advance®), comparando dichos valores con las referencias de la literatura y analizándose estadísticamente con arreglo a la clasificación Z para el IMC de la OMS.

ResultadosSe analizaron 45 individuos, con una prevalencia del 58% en niñas, con edad media de 11 años, siendo el 35,5% de ellas obesas con arreglo a la clasificación Z para el IMC de la OMS. El 57,1% del subgrupo de individuos eutróficos con SD valorados mediante el IMC de la OMS reflejaron valores alterados de la composición corporal.

ConclusiónLa puntuación Z para el IMC de la OMS en pacientes con SD se corresponde con la composición corporal únicamente en individuos clasificados de sobrepeso u obesidad mediante la puntuación Z para el IMC. Se concluye que el IMC no es una herramienta adecuada para calcular la composición corporal en niños con SD.

Down syndrome (DS) is the most common aneuploidy among the human species, occurring 1 time for each 600–800 newborns. The average life expectancy of DS has been growing in the last decades, from 35 years to 60 years old nowadays.1–3 This fact alone implicates in high costs for every health system, which is justified by a greater prevalence of comorbidities in this specific population.4

These comorbidities may vary from hearth diseases, hypothyroidism, orthopedic issues, to child obesity,2,5 that is a modern and enormous problem, which is growing in developed as well undeveloped countries.

Although there is a high prevalence of obesity in the general population, there is little information about the obesity in DS children around the globe. Many authors have described a high prevalence of weight excess in adults with DS using general BMI classifications indiscriminately.6–8 These reports may not reflect exclusive characteristics from DS individuals, justified by some differences found in the body composition between a DS adult group and the general population,9 in which they showed similar percentages of body fatness, but lower bone density and less muscle mass. Therefore, such findings may suggest that BMI (body mass index) may not be the perfect tool to evaluate such individuals.1,8

If there is an objective of controlling risk factors in childhood in DS population, there is a need for accurate evaluation, with modern techniques to conclude what may be the best way to assess and care obesity in this situation.

ObjectiveThe obesity high prevalence and its negative consequences for the DS population are stakes to the need for health programs and specific medical interventions to be created for them.2,6 It needs a better way of obesity classification specially in the childhood for correct decisions.10–12 This research is to make the organic characteristics of this population clear enough to be able to help create new strategies in DS health care and discover the possibility that DS children have higher body fat percentage than assessed by BMI charts.

MethodsIt was collected data from 45 children with DS randomly, including age, sex, weight, height and pubertal status according to their ages (above 8 years old girls and above 9 years old boys as pubertal ages). All of them were part of the Ambulatório Multidisciplinar de Orientação à Síndrome de Down da Santa Casa de São Paulo AMOR/SDSC, and their BMI values were calculated and then classified using the z-score tables from World Health Organization (WHO).

The children had their body composition assessed at the same day their data was retrieved, by the dual X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) technique by Lunar Prodigy Advance®.10 The technique was chosen by its high accuracy in measuring body fat percentages and its security.

The DXA estimates lean body mass, body fat, and bone mineral density by using the differential absorption of X-ray or photon beams of two levels of intensity. DXA relies on the principle that the intensity of an X-ray or photon beam is altered by the thickness, density, and chemical composition of an object in its path. In children, the scan takes approximately 10min. The average radiation dose, depending on the instrument and body size, is 0.04–0.86mRem, less than the average exposure of a chest radiograph. The precision of DXA (coefficient of variation) is less than 2 percent.10

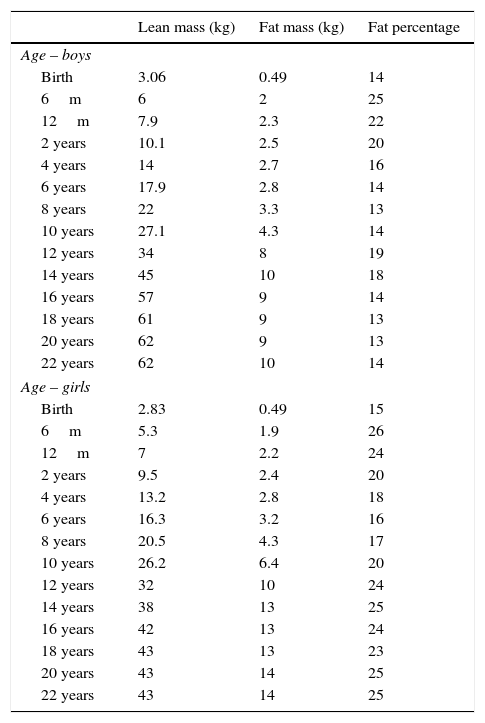

The results were compared to the general population tables offered by international and Brazilian standards, which uses values from Buchman et al. and MacCarthy et al.10,13 (Table 1).

Body composition by age and genre.

| Lean mass (kg) | Fat mass (kg) | Fat percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age – boys | |||

| Birth | 3.06 | 0.49 | 14 |

| 6m | 6 | 2 | 25 |

| 12m | 7.9 | 2.3 | 22 |

| 2 years | 10.1 | 2.5 | 20 |

| 4 years | 14 | 2.7 | 16 |

| 6 years | 17.9 | 2.8 | 14 |

| 8 years | 22 | 3.3 | 13 |

| 10 years | 27.1 | 4.3 | 14 |

| 12 years | 34 | 8 | 19 |

| 14 years | 45 | 10 | 18 |

| 16 years | 57 | 9 | 14 |

| 18 years | 61 | 9 | 13 |

| 20 years | 62 | 9 | 13 |

| 22 years | 62 | 10 | 14 |

| Age – girls | |||

| Birth | 2.83 | 0.49 | 15 |

| 6m | 5.3 | 1.9 | 26 |

| 12m | 7 | 2.2 | 24 |

| 2 years | 9.5 | 2.4 | 20 |

| 4 years | 13.2 | 2.8 | 18 |

| 6 years | 16.3 | 3.2 | 16 |

| 8 years | 20.5 | 4.3 | 17 |

| 10 years | 26.2 | 6.4 | 20 |

| 12 years | 32 | 10 | 24 |

| 14 years | 38 | 13 | 25 |

| 16 years | 42 | 13 | 24 |

| 18 years | 43 | 13 | 23 |

| 20 years | 43 | 14 | 25 |

| 22 years | 43 | 14 | 25 |

The present study was accepted by the ethical committee of the Hospital da Santa Casa de Misericórdia de São Paulo.

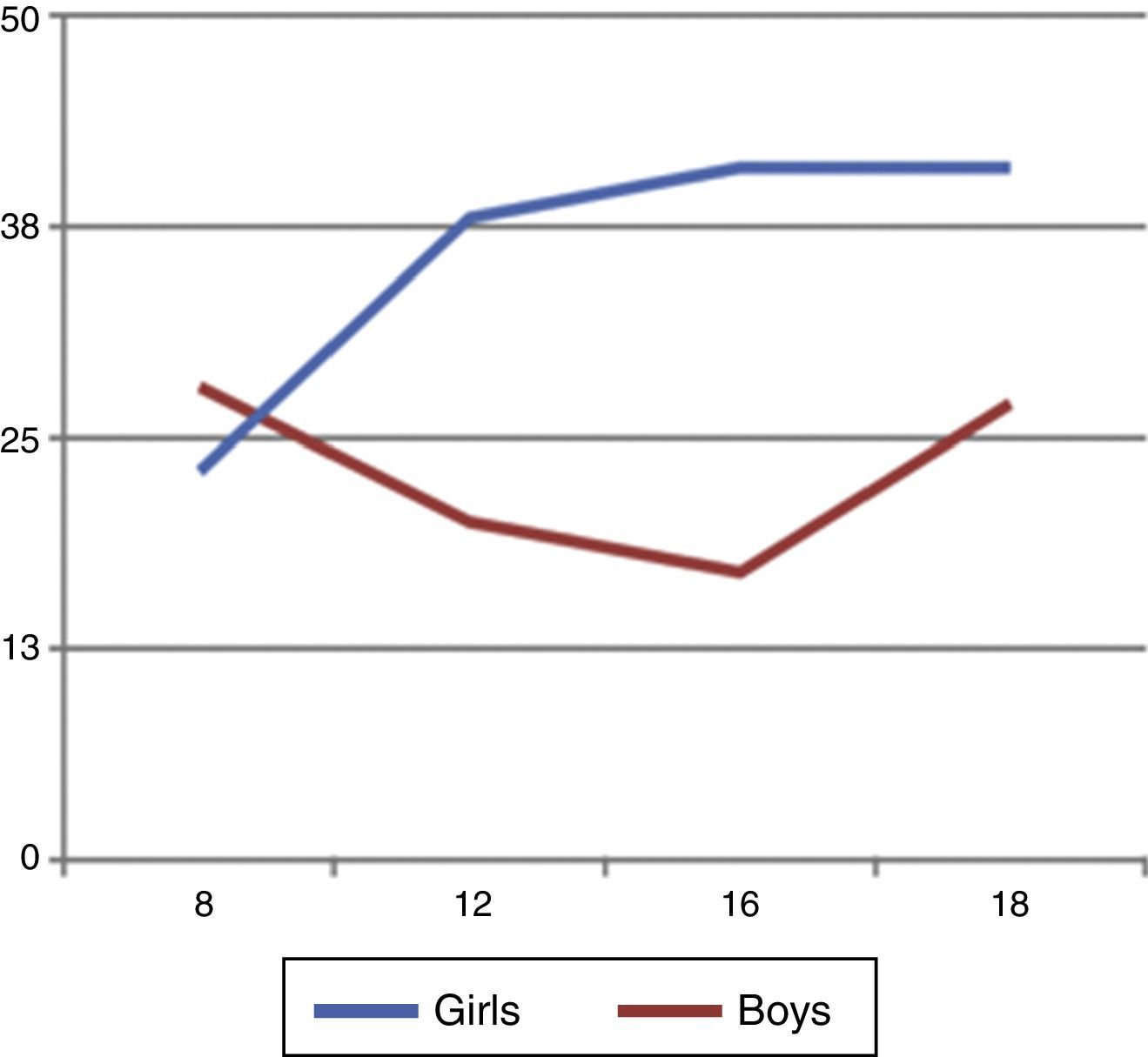

ResultsThe group was characterized by 42% of boys and 58% of girls, with a mean age of 11.2 years old and a mode of 10 years old. It was found that 35.5% of them were obese by the WHO z-score classification and 17.7% were overweight, and only 51.1% classified as having the ideal weight. The obesity was more common among the girls with 46.1% against 21% of obesity prevalence among the boys, and this difference was even more clear after the pubertal age (Fig. 1).

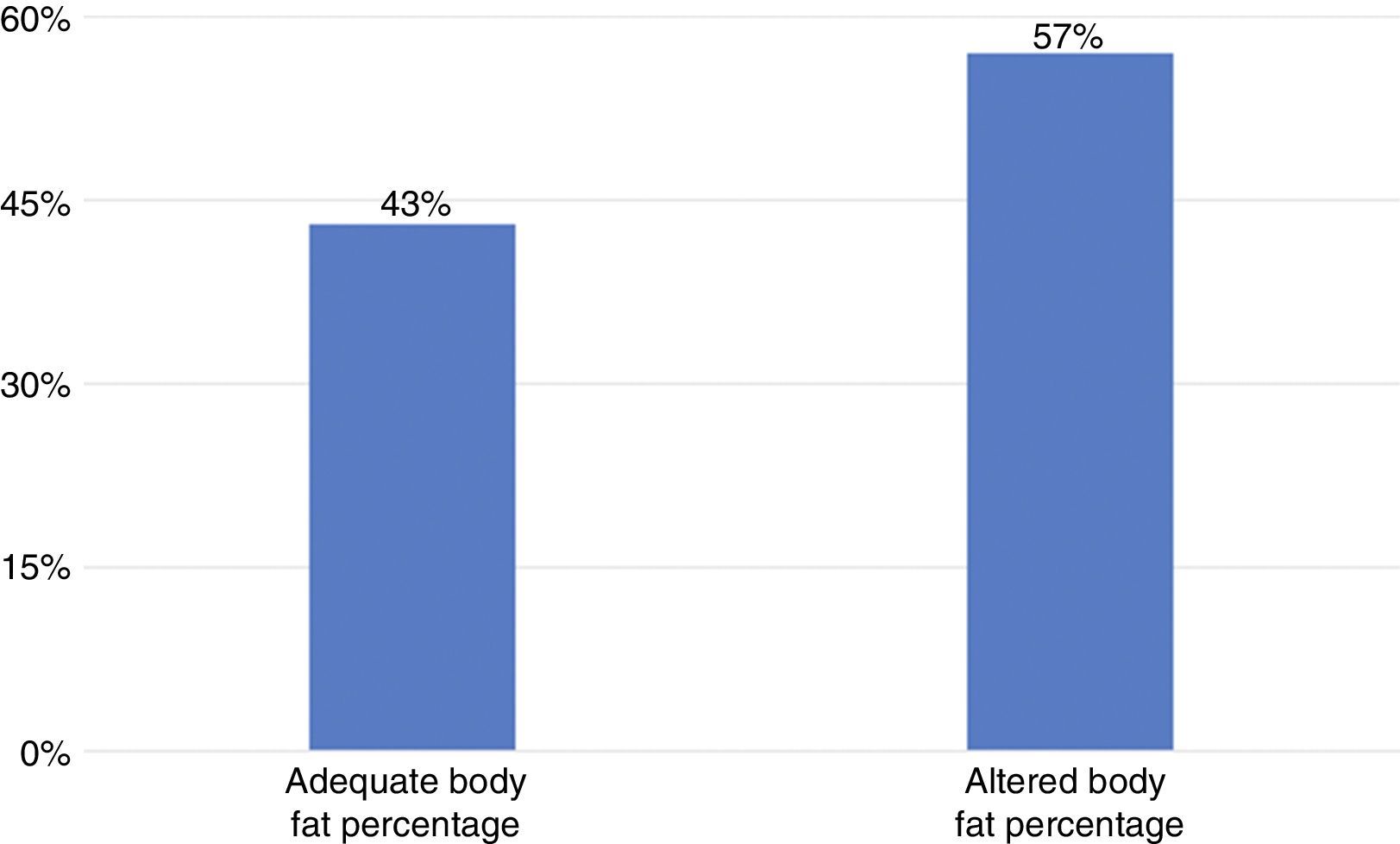

The present study continues with the analysis of the crossed frequencies between BMI and DXA references.7,13 It was found that 57% of the DS children that were evaluated and classified as adequate, accordingly to WHO BMI z-score, actually had altered body fat percentages. Due to validate this statistical difference it was applied the qui-square test and verified a p-value<0.0001 for our references, which means that the statistical error to classify obesity using the OMS BMI z-score charts in this group was extremely elevated, probably misguiding the ideal health care for these children.

Thereafter, the data was divided into four groups of interest, in which we had boys, girls and their pubertal status. Because of the restrict number of these fragments, in some cases the proportional tests were not applied.

The most significant findings were for the pre-pubertal age girls segment, whose result was a small group with 5 children in which there was no conflict between BMI z-score and body fat percentage by DXA. Otherwise, for the post-pubertal age girls the illustration was found for 21 individuals, with 7 cases of BMI being classified as normal while all of them had altered body fat percentage by both Buchman et al. and MacCarthy et al.13 DXA values, with a p<0.0001.

Finally, a graphic was tailored with body fat percentage found through the studied individuals age, categorized in 0–4 years, 5–8, 9–12, 13–16, and above 16 years old. The designed curves showed that the girls had an everlasting body fat percentage increase, specially after the post-pubertal ages, while the boys had a tendency to decrease their body fat percentage after the post-pubertal ages with an increase after 16 years old.

ConclusionThe DS patients with adequate BMI according to WHO z-score classification do not have statistical correlation with their DXA body composition values, justified by the high levels of body fat percentage found among them.

These findings tie in the hypothesis that there is indeed a high prevalence of obesity in DS children, with a predominance of this characteristics in DS girls, which have greater prevalence of high body fat percentage than boys, specially after their pubertal ages. This observation may be explained by the hormonal changes and differences between the genre and age groups.

In Fig. 2 it is shown the statistical difference found among the adequate BMI group by the WHO BMI z-score and their body composition by DXA findings with p<0.0001. This allows the conclusion that BMI is not an accurate tool to assess the body composition among DS children, specially the ones within its adequate z-score range. This helps us to understand the need of specific health care strategies for DS, that may be having their comorbidities underestimated by the regular use of general clinical evaluation tools.

The clinical following of DS children with adequate BMI should be completed with a DXA body composition analysis to accurate evaluation of its metabolic status. If it is not possible to be done, these children should be taken care as if they had high body fat percentages.

The solution to solve this question is to raise awareness in DS children health care, that needs to be reviewed and updated to their new social status won by their greater life expectancy and power to make the difference in our society.

Conflicts of interestThe authors do not have any financial or personal relationship which can cause a conflicts of interest regarding this article.