To evaluate the quality of life (QOL) of parents of children with asthma and to analyze the internal consistency of the generic QOL tool World Health Organization Quality of Life, abbreviated version (WHOQOL-BREF).

MethodsWe evaluated the QOL of parents of asthmatic and healthy children aged between 8 and 16, using the generic WHOQOL-BREF questionnaire. We also evaluated the internal consistency using Cronbach's alpha (αC), in order to determine whether the tool had good validity for the target audience.

ResultsThe study included 162 individuals with a mean age of 43.8±13.6 years, of which 104 were female (64.2%) and 128 were married (79.0%). When assessing the QOL, the group of parents of healthy children had higher scores than the group of parents of asthmatic children in the four areas evaluated by the questionnaire (Physical, Psychological Health, Social Relationships and Environment), indicating a better quality of life. Regarding the internal consistency of the WHOQOL-BREF, values of αC were 0.86 points for the group of parents of asthmatic children, and 0.88 for the group of parents of healthy children.

ConclusionsParents of children with asthma have impaired quality of life due to their children's disease. Furthermore, the WHOQOL-BREF, even as a generic tool, showed to be practical and efficient to evaluate the quality of life of parents of asthmatic children.

Avaliar a qualidade de vida (QV) de pais de crianças asmáticas e analisar a consistência interna do instrumento genérico de qualidade de vida World Health Organization Quality of Life, versão abreviada (WHOQOL-BREF).

MétodosFoi avaliada a QV de pais de crianças asmáticas e hígidas entre oito-16 anos, por meio do questionário genérico WHOQOL-BREF. Foi avaliada também a consistência interna, por meio do alfa de Cronbach (αC), para determinar se o instrumento tem boa validade para o público alvo.

ResultadosParticiparam do estudo 162 indivíduos, com idade média de 43,8±13,6 anos, dos quais 104 eram do sexo feminino (64,2%) e 128 casados (79,0%). Na avaliação do nível de qualidade de vida, o grupo de pais de crianças saudáveis apresentou escores acima do grupo de pais de asmáticos nos quatro domínios do instrumento (físico, psicológico, social e meio ambiente) que indicam melhor qualidade de vida. Na análise de consistência interna, o WHOQOL-BREF obteve valores de αC=0,86 pontos para o grupo de pais de asmáticos e 0,88 para o grupo de pais de hígidos.

ConclusõesPais de crianças asmáticas apresentam comprometimento da qualidade de vida em função da doença de seus filhos. Além disso, o WHOQOL-BREF, mesmo sendo um instrumento genérico, se mostrou prático e eficiente para avaliar a qualidade de vida de pais de crianças asmáticas.

Asthma is a chronic disease with high prevalence in childhood,1 which requires coordinated efforts between children, families and health professionals for its control and treatment.2 The disease treatment involves pharmacological and behavioral recommendations to prevent and control its exacerbations; however, asthma management is made difficult by the patients and their caregivers, who often do not adhere to the prescribed recommendations.3 One of the factors for poor adherence to treatment is related to the inadequate knowledge of caregivers on preventive medications for the disease.4 In turn, non-adherence to treatment results in lack of control, generating many complications in children and their caregivers, resulting in a decrease in quality of life for both.3

Therefore, taking care of children with asthma has a significant impact on the family members.5 The burden of caring for a chronically ill child is associated with parents’ health deterioration, leading to adverse health outcomes, such as emotional stress and depression.6 Allergic diseases consist of a variety of disorders that have different symptoms, leading to a multifaceted impact on many aspects of family life.7 In this sense, children with asthma can suffer an impact on questions related to education, sleep quality, physical limitations, symptom control and behavioral or development problems.8 Parents can also have problems maintaining normal family and daily life functions, resulting in a decrease in quality of life.9

Although several tools have been developed to measure the burden or the impact felt by parents when caring for children with chronic diseases, no specific tool was developed to measure the quality of life of parents that provide health care to children with asthma in Brazil.10 The existing tools are generic questionnaires assessing the quality of life in the general context, regardless of how the disease affects the family context.11 Currently, the most often used questionnaire in studies involving quality of life in chronic diseases is the one by the World Health Organization (World Health Organization Quality of Life – WHOQOL), which is useful in epidemiological studies or clinical trials, as well as to evaluate the effectiveness of treatments and disease control.12

Because asthma is a disease with high prevalence in childhood, which leads to complications for both children and family members, the present study had the primary objective of evaluating the quality of life of parents caring for children with asthma followed at an outpatient clinic of a reference center in southern Brazil. As there is no specific tool for assessing the quality of life of caregivers of children with asthma, the secondary objective was to evaluate the internal consistency of the World Health Organization Quality of Life–short version (WHOQOL-BREF) to ensure that it is valid for the study group.

MethodThe participants were parents and caregivers of children with physician-diagnosed asthma being followed in the reference center for pediatric asthma in southern Brazil, as well as parents of clinically healthy children. As inclusion criteria, children with a diagnosis of asthma should have been followed for at least 12 months, and in the group of healthy children, parents could not have had direct contact with the disease, such as a second child with asthma. As exclusion criteria, the parents in both groups could not have a diagnosis of asthma or any other chronic disease that could interfere with the study results. Additionally, patients could not have any other chronic diseases that might interfere with the evaluation of the WHOQOL-BREF. For data analysis, the groups were divided into (Parents of asthmatic children) and (Parents of healthy children). For sample calculation, taking into account the population being followed at the reference center, assuming a 95% confidence level and a standard margin of error of 5%, it would be necessary to assess 48 parents and/or caregivers of asthmatic children for the study. In addition, we adopted the criterion of two participants in the healthy group for each participant in the asthmatic group.

To assess the quality of life we used the World Health Organization WHOQOL-BREF tool,13 which consists of 26 questions with structured responses on a Likert scale of five points. The questionnaire was self-administered, according to the perception of the last two weeks. Of the 26 questions, two assess the perception of quality of life and health of the patient, and the others (24 questions) comprise the physical, psychological, social and environment domains. In addition to the WHOQOL-BREF, a general questionnaire was applied to characterize the sample, consisting of ten questions.

The studied psychometric property was the internal consistency by Cronbach's alpha (α-C),14 which assesses whether a tool is capable of always measuring what is to be measured in the same way, producing an average correlation between questions and responses. Thus, the αC coefficient is calculated from the variance of the individual items and the variance of the sum between items, by verifying whether all of them use the same measuring scale. Values were considered acceptable for α-C scores >0.70 and <0.95.

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio Grande do Sul (PUCRS) under the number 11/05602. Moreover, all participants received and signed the informed consent form (ICF), agreeing to participate in the study.

Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics v.20 software (International Business Machines –– Statistical Product and Service Solutions, New York, USA). For descriptive analysis, categorical data were described as absolute and relative frequencies. The description of continuous variables was represented by mean and standard deviation (SD). Associations between the outcome variables and between groups of schoolchildren (parents of asthmatics and parents of healthy children) were evaluated using mixed linear models. For purposes of psychometric analysis, Cronbach's alpha tests (αC)14 and the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) were applied.15 The significance level was set at p<0.05.

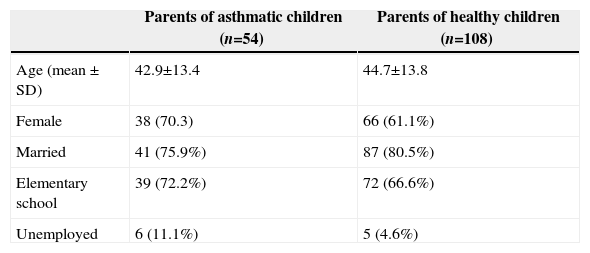

ResultsThe study included 162 subjects, 54 parents of asthmatic and 108 parents of healthy children, with a mean age of 43.8±13.6 years. Of these, 104 were females (64.2%), 111 with predominantly elementary education (68.5%), and 128 with a current marital status of ‘married’ (79.0%). The comparison of the general characteristics of parents of asthmatics and parents of healthy children is shown in Table 1.

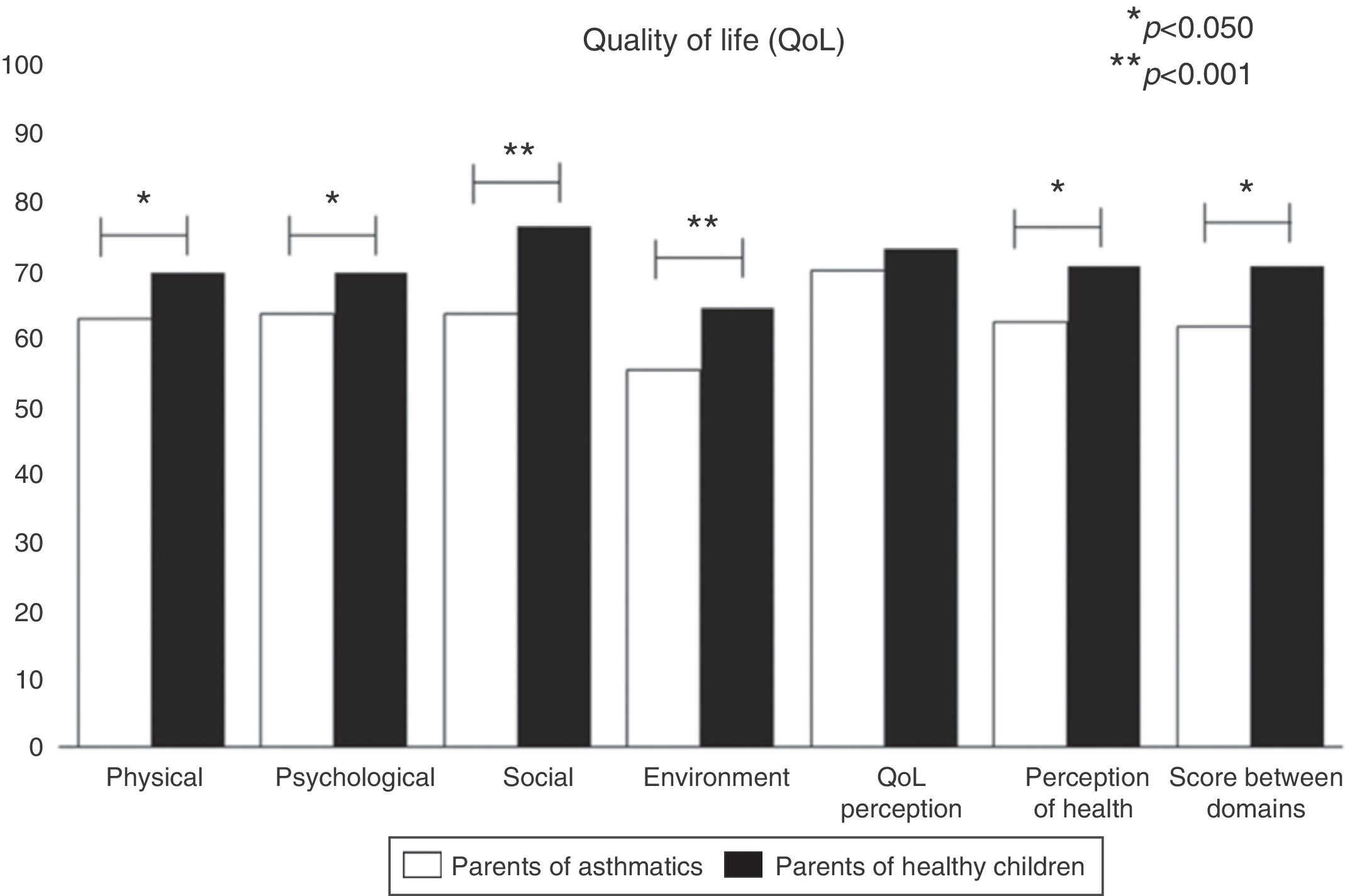

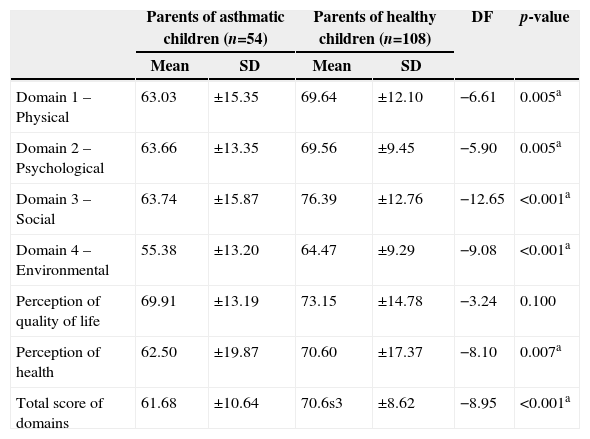

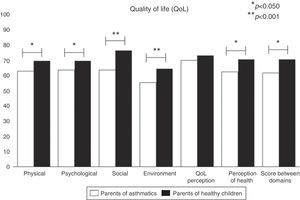

When comparing the quality of life level between the two groups (Table 2 and Fig. 1), the group of parents of healthy children had higher scores than the group of parents of asthmatic children in the four domains of the questionnaire, as well as for the health perception and the total score. There were no differences between the groups only for the question about the quality of life perception.

Comparison of levels of quality of life between groups of parents of asthmatic and healthy children using the WHOQOL-BREF questionnaire, assessed in Porto Alegre, RS, in the 2013/2014 period. Data shown as mean±SD.

| Parents of asthmatic children (n=54) | Parents of healthy children (n=108) | DF | p-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |||

| Domain 1 – Physical | 63.03 | ±15.35 | 69.64 | ±12.10 | −6.61 | 0.005a |

| Domain 2 – Psychological | 63.66 | ±13.35 | 69.56 | ±9.45 | −5.90 | 0.005a |

| Domain 3 – Social | 63.74 | ±15.87 | 76.39 | ±12.76 | −12.65 | <0.001a |

| Domain 4 – Environmental | 55.38 | ±13.20 | 64.47 | ±9.29 | −9.08 | <0.001a |

| Perception of quality of life | 69.91 | ±13.19 | 73.15 | ±14.78 | −3.24 | 0.100 |

| Perception of health | 62.50 | ±19.87 | 70.60 | ±17.37 | −8.10 | 0.007a |

| Total score of domains | 61.68 | ±10.64 | 70.6s3 | ±8.62 | −8.95 | <0.001a |

DF, difference between groups; SD, standard deviation.

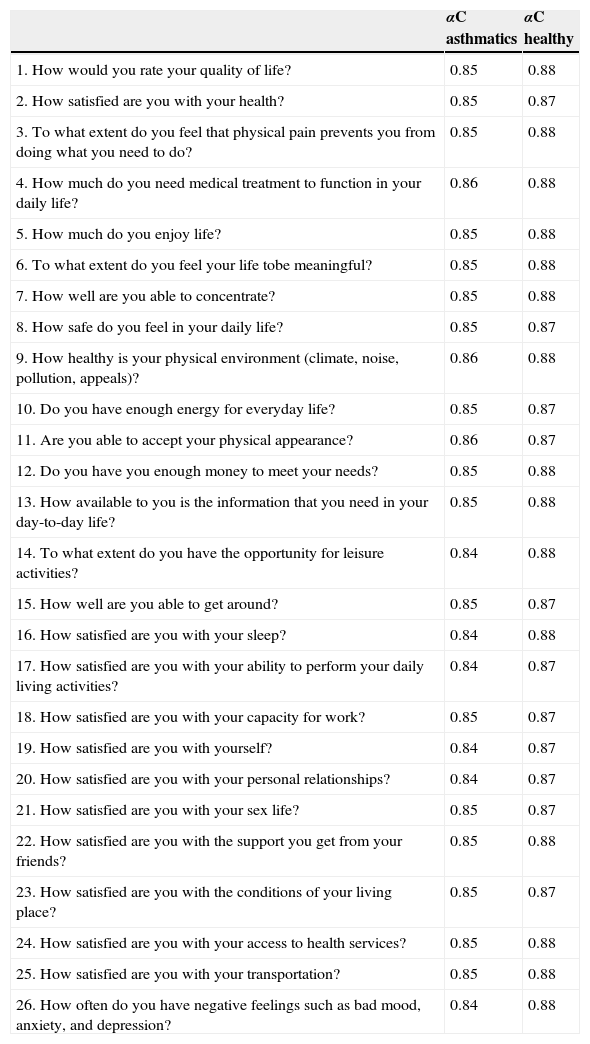

For internal consistency, the αC was applied to both the total score (26 items) and the score per item (Table 3). In the analysis of the total score, the tool obtained a value of αC=0.86 points for the group of parents of asthmatics and 0.88 for the group of parents of healthy children. These values show a strong internal consistency both between items and in the total, as scores <0.70 are considered highly relevant. For correlation purposes, the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) was applied, yielding values of 0.85 points (p<0.001) for the group of parents of asthmatics and 0.88 (p<0.001) for the group of parents of healthy children, with a 95% confidence interval (95%CI: 0.79–0.90 and 0.87–0.89, respectively).

Assessment of internal consistency of the items (WHOQOL-BREF questionnaire questions) using Cronbach's alpha coefficient (αC) applied to groups of parents of asthmatic and parents of healthy children.

| αC asthmatics | αC healthy | |

|---|---|---|

| 1. How would you rate your quality of life? | 0.85 | 0.88 |

| 2. How satisfied are you with your health? | 0.85 | 0.87 |

| 3. To what extent do you feel that physical pain prevents you from doing what you need to do? | 0.85 | 0.88 |

| 4. How much do you need medical treatment to function in your daily life? | 0.86 | 0.88 |

| 5. How much do you enjoy life? | 0.85 | 0.88 |

| 6. To what extent do you feel your life tobe meaningful? | 0.85 | 0.88 |

| 7. How well are you able to concentrate? | 0.85 | 0.88 |

| 8. How safe do you feel in your daily life? | 0.85 | 0.87 |

| 9. How healthy is your physical environment (climate, noise, pollution, appeals)? | 0.86 | 0.88 |

| 10. Do you have enough energy for everyday life? | 0.85 | 0.87 |

| 11. Are you able to accept your physical appearance? | 0.86 | 0.87 |

| 12. Do you have you enough money to meet your needs? | 0.85 | 0.88 |

| 13. How available to you is the information that you need in your day-to-day life? | 0.85 | 0.88 |

| 14. To what extent do you have the opportunity for leisure activities? | 0.84 | 0.88 |

| 15. How well are you able to get around? | 0.85 | 0.87 |

| 16. How satisfied are you with your sleep? | 0.84 | 0.88 |

| 17. How satisfied are you with your ability to perform your daily living activities? | 0.84 | 0.87 |

| 18. How satisfied are you with your capacity for work? | 0.85 | 0.87 |

| 19. How satisfied are you with yourself? | 0.84 | 0.87 |

| 20. How satisfied are you with your personal relationships? | 0.84 | 0.87 |

| 21. How satisfied are you with your sex life? | 0.85 | 0.87 |

| 22. How satisfied are you with the support you get from your friends? | 0.85 | 0.88 |

| 23. How satisfied are you with the conditions of your living place? | 0.85 | 0.87 |

| 24. How satisfied are you with your access to health services? | 0.85 | 0.88 |

| 25. How satisfied are you with your transportation? | 0.85 | 0.88 |

| 26. How often do you have negative feelings such as bad mood, anxiety, and depression? | 0.84 | 0.88 |

αC, Cronbach's alpha; Asthmatics, Group of parents of children with asthma; Healthy children, Group of parents of healthy children.

The assessment of quality of life has taken on a key role in the clinical area, regarding the individual or collective perception of patients with certain chronic diseases, which they can maintain somewhat under control due to therapeutic advances. The fact that patients benefit from survival, sometimes for long periods, does not mean “living well”, as there are often limitations, with losses in several activities of daily living. However, this fact goes far beyond patient limitations, as in the case of children diagnosed with asthma, in which parents or guardians end up being directly affected by the disease.

This study shows that parents of children with asthma have their quality of life standards below the levels of healthy children's caregivers. Using the WHOQOL-BREF tool, one can observe that in the four central domains of the study (physical, psychological, social and environmental), caregivers of asthmatic children showed significantly lower values, in addition to their own perception of health, when compared with the group of parents of healthy children. Furthermore, with the secondary objective of evaluating the internal consistency, the tool showed values above the mean of quality of life tools,11 demonstrating that it concisely measures the answers. Using the same instrument, Crespo et al.16 investigated the impact of the disease on 97 caregivers of children with asthma. The authors concluded that the family factors are key components to understanding the quality of life not only of children with the disease but also of their caregivers. Among the family factors, family resources were analyzed (material and assistance), as well as family challenges (future perspectives). Such factors are potentially modifiable, and can be included in practical interventions aiming at improving the quality of life of family members.17 The family resources were identified as the positive aspects of the family, that is, parents and children perceiving a consistent family environment, facilitating communication and the expression of thoughts and feelings. Family challenges refer to the burden experienced by the caregiver, regarding the negative impact the disease can bring to the family environment.18,19 These two factors are usually affected, because caregivers can rarely maintain a stable professional life, as they usually need to meet the additional demands generated by the disease.20

Recently, Silva et al.21 published a study associating the high levels of care burden to impaired quality of life of parents of asthmatic children. A total of 180 parents of asthmatic children (aged 8–18 years) were evaluated, who reported their experience regarding care of the disease, the use of positive reformulation in coping and their quality of life. The authors suggest that psychological interventions focused on the recognition and appreciation of care, together with the positive revaluation of the stressful situation, can support the coping strategies and improve the parents’ quality of life. However, dissimilarly from the present study, significant values were only found for the social domain. According to other studies,22–25 parents of children with chronic diseases, such as asthma, keep closer social relationships, used as a basis for support and skills to cope with the disease.

Gau et al.26 developed a study to validate the WHOQOL-BREF questionnaire applied to 229 caregivers of asthmatic children in Taiwan. In this study, the value of Cronbach's α ranged from 0.64 to 0.84, values that are lower than those found in the present study (0.84 to 0.86). As a result, the authors demonstrated that physical health and psychological health are the two areas that have an impact on the quality of life of this population.26 In the present study, the values were different for the four domains (physical, emotional, social and environmental), in addition to the perception of health category. The authors state that the physical strength levels are low due to sleep interruption, loss of energy and somatic complaints, influencing not only the physical health perception, but also the negative feelings that, in turn, directly interfere with the perception of the psychological domain. Additionally, environmental factors, including pollution, noise, traffic and weather, also affect the quality of life of mothers and their children in Taiwan. Finally, they concluded that the tool used in the study was valid and reliable for assessing the quality of life of caregivers of children with asthma.26

Moreira et al.27 compared the quality of life of parents of children with different chronic conditions (asthma, diabetes, epilepsy and obesity) and parents of healthy children, totaling 964 families with children aged between 8 and 18 years. As a result, they showed that parents of obese children had lower levels of quality of life, compared not only with parents of children with normal weight, but also with parents of children with asthma and children with epilepsy. Additionally, they found a consistent pattern in the assessed conditions for the associations between the quality of life of parents and their children, with the exception of asthma, as the values showed low variation in quality of life scores related to the disease. The authors concluded the study by reinforcing that pediatricians not only should evaluate children with chronic diseases, but also evaluate or refer to follow-up the parents with psychosocial difficulties that might interfere with the health and well-being of their children.

As the main limitation of the study, we point out the lack of a specific tool to assess the quality of life of parents of children with asthma in Portuguese (Brazilian Portuguese). Since 2011, there is a special tool to assess the quality of life of caregivers of children with asthma, called Cuestionario de Impacto Familiar del Asma Bronquial Infantil (IFABI-R).28 The IFABI-R questionnaire consists of three domains (functional, emotional and socio-occupational) and has good psychometric analysis, but it is applied to the Spanish public. In order to apply it to Brazilian caregivers, prior linguistic and cultural validation would be required. It is noteworthy that, even if the WHOQOL-BREF has been shown to have high internal consistency, the items are not specific for asthma.

This study showed that asthma can compromise the quality of life of parents of asthmatic children, who end up suffering the impact of the disease morbidity. Regarding the tool used to assess quality of life, it is possible to state that it can be safely and effectively applied to parents of children with asthma, as long as its internal consistency is analyzed.

FundingConselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq), by way of a starting grant.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.