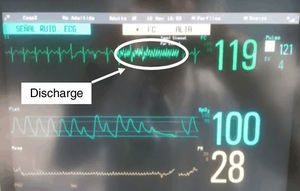

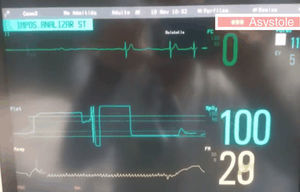

Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), is still, even today, one of the main treatments used in psychiatry for profound depression.1 We present the case of a 66-year-old woman, diagnosed with severe depressive syndrome, with psychotic symptoms, who had been treated with ECT since 2004, with good response and no hemodynamic alterations during the treatment, without other relevant history. The therapy consisted of provoking a slight convulsion, in this case a right unilateral convulsion with brief pulses of 900mA to 70Hz in 1ms, under sedation using atropine 0.5mg, propofol 90–100mg and succinylcholine 50mg, after placement of dental protection. On the day in which she developed asystole, she arrived for treatment with a heart rate of 120bpm; for that reason, she was not given atropine, but propofol and succinylcholine were administered at the same dosages as in previous treatments. After administering the standard discharge, asystole lasting 5s was seen, with spontaneous recuperation of rhythm (Figs. 1 and 2).

DiscussionPost-ECT mortality is low, representing 0.002%, although this varies according to the series from 1:10,000 to 1:50,000. The main complications are cardiological, principally arrhythmias.2 Post-ECT asystole, recognized as a heart rate <12bpm for at least 5s, is a complication that is seldom seen, but it can be fatal.3 The mechanism of production is believed to be the result of a parasympathetic discharge, through a central stimulus that acts on the muscarinic receptors of the sinoatrial node via the vagus nerve after applying the stimulus to the patient.2 Cardiovascular response during ECT has 2 phases: the first takes place when the discharge is administered, and consists of lowering the heart rate through vagal stimulation. This bradycardia lasts only a brief time and usually resolves spontaneously in the majority of the cases. During the second phase, after the convulsion, a severe sympathetic discharge is produced, which is what is responsible for the tachycardia and postictal arterial hypertension.

Various factors of clinical risk related with the development of asystole have been studied, among which the following are included: non-geriatric adults (age <65 years), males, no relevant cardiological history, normal BMI, use of anticholinergics in previous ECTs, resting heart rate <60bpm, use of pre-ECT beta-blockers as prophylaxis to prevent severe post-ECT high blood pressure, use of monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs), post-ECT bradycardia in previous treatments and subconvulsive stimuli.

There have been cases of asystole in patients treated previously with ECT with no presentation of any incidence. For that reason, the absence of prior complications does not guarantee that they will not appear in the future.

Characteristics of the ECT itself have also been analyzed. A lower incidence of asystole has been observed following unilateral administration of maximum charge with short 2-s pulses as compared to that of 4s.4 In another observational study,5 the placement of the electrodes and the development of bradycardia and asystole were analyzed. The authors concluded that the patients treated with electrodes in bifrontal placement showed fewer changes in heart rhythm than those treated with a unilateral placement. However, it could not be concluded that unilateral or bitemporal placement in presence of premedication with atropine was more dangerous compared with the bifrontal.

In the case presented here, we can see that the treatment administered was short pulse right unilateral at 70%–80% of the maximum charge dosage in 1 and 4ms. The patient received treatment with atropine due to low basal heart rates, except for the day in which she presented the asystole; no atropine was administered that day because she presented tachycardia before the ECT. The administration of 0.5mg of atropine as a prophylaxis prevented further episodes of asystole.

There are very few clinical studies. This, together with the fact that the majority of the literature related to post-ECT asystole are clinical cases, makes it difficult to define factors of risk linked to this complication, which is potentially fatal even though it is rare. The majority of authors conclude that prophylactic administration of atropine, between 0.5 and 0.8mg, is usually effective in avoiding the development of asystole, along with close monitoring of heart rate during ECT.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Romero P, Telletxea S S, Saez E, Arzuaga MA. Asistolia tras terapia electroconvulsiva. Rev Psiquiatr Salud Ment (Barc). 2017;10:61–62.