Having read the recent letter to the editor from Xifró et al.1 on post-traumatic psychiatric evaluation, we have no choice but to join in on such sound indications and comments about the limitations in the section on psychiatry of the new scale in Law 35/2015,2 and to emphasise the difficulties with respect to the terminology that it uses, which is not consistent with that used in the official classifications of mental disorders. There are specific aspects, not indicated by the authors mentioned above, related to the chapter on cognitive disorders and neuropsychological damage, which we understand should be likewise emphasised and likewise relevant for professionals in mental health and psychiatry.

Organic personality disorder is now grouped together with frontal lobe syndrome and the alteration of higher brain functions integrated in the section of neurological sequelae (Table 1). We understand that this shows a greater epistemological coherence and forces a comprehensive and interdisciplinary perspective of the injured individual. In the context of the previous scale,3 the assessor frequently faced the contradiction between application norms that prohibited duplicity and the division of a specific clinical picture of neurocognitive affectation between the section on neurological syndromes of central origin and that of psychiatric syndromes.4 With respect to this, in the current scale we can highlight the specific reference to amnesia as not assessable independently, but rather only as a part of a more global cognitive disorder; again, this is more coherent, although curious due to its presentation in the table.2

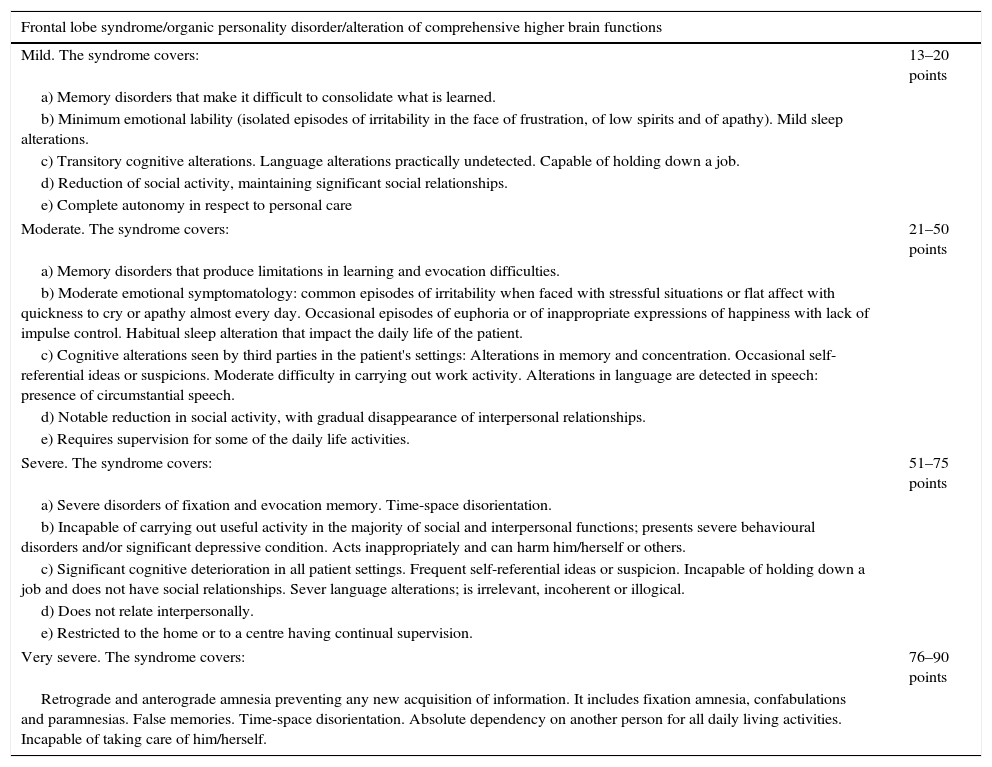

Extract from Table 2.A.1. Medical scale, classification and evaluation of sequelae.

| Frontal lobe syndrome/organic personality disorder/alteration of comprehensive higher brain functions | |

|---|---|

| Mild. The syndrome covers: | 13–20 points |

| a) Memory disorders that make it difficult to consolidate what is learned. | |

| b) Minimum emotional lability (isolated episodes of irritability in the face of frustration, of low spirits and of apathy). Mild sleep alterations. | |

| c) Transitory cognitive alterations. Language alterations practically undetected. Capable of holding down a job. | |

| d) Reduction of social activity, maintaining significant social relationships. | |

| e) Complete autonomy in respect to personal care | |

| Moderate. The syndrome covers: | 21–50 points |

| a) Memory disorders that produce limitations in learning and evocation difficulties. | |

| b) Moderate emotional symptomatology: common episodes of irritability when faced with stressful situations or flat affect with quickness to cry or apathy almost every day. Occasional episodes of euphoria or of inappropriate expressions of happiness with lack of impulse control. Habitual sleep alteration that impact the daily life of the patient. | |

| c) Cognitive alterations seen by third parties in the patient's settings: Alterations in memory and concentration. Occasional self-referential ideas or suspicions. Moderate difficulty in carrying out work activity. Alterations in language are detected in speech: presence of circumstantial speech. | |

| d) Notable reduction in social activity, with gradual disappearance of interpersonal relationships. | |

| e) Requires supervision for some of the daily life activities. | |

| Severe. The syndrome covers: | 51–75 points |

| a) Severe disorders of fixation and evocation memory. Time-space disorientation. | |

| b) Incapable of carrying out useful activity in the majority of social and interpersonal functions; presents severe behavioural disorders and/or significant depressive condition. Acts inappropriately and can harm him/herself or others. | |

| c) Significant cognitive deterioration in all patient settings. Frequent self-referential ideas or suspicion. Incapable of holding down a job and does not have social relationships. Sever language alterations; is irrelevant, incoherent or illogical. | |

| d) Does not relate interpersonally. | |

| e) Restricted to the home or to a centre having continual supervision. | |

| Very severe. The syndrome covers: | 76–90 points |

| Retrograde and anterograde amnesia preventing any new acquisition of information. It includes fixation amnesia, confabulations and paramnesias. False memories. Time-space disorientation. Absolute dependency on another person for all daily living activities. Incapable of taking care of him/herself. | |

As for the set of organic personality disorder, frontal lobe syndrome and alteration of higher integrated brain functions, the current scale maintains for this set of sequelae a score divided into ranges (mild, moderate, serious and very serious), along with a sequela called “Post-concussion Syndrome/Mild Cognitive Disorder” that cross-references to ICD-105 and DSM-56 criteria and involves a lesser affectation than the rest. The scale establishes the deficits that each range covers jointly for all the sequelae that it encompasses. This differs from what is established in the two main diagnostic manuals (ICD and DSM), not only in the term chosen, but also in the characterisation of the clinical picture. The ICD-105 (whose new version is planned for 2018 and uses the term “secondary personality change”7) indicates that this disorder is characterised by a significant alteration of the usual forms of premorbid behaviour, with profound affectation of emotions, needs and impulses, possibly affecting cognitive processes, and requires at least 2 of the 6 features described for its diagnosis. The DSM-56 presents the “personality change due to other medical condition”, which involves a persistent alteration of the personality constituting a change with respect to the previous characteristic personality pattern of the individual and that produces an alteration in social, job or other areas of functioning. In addition, it recommends the establishment of the type of dominant characteristic (affective lability, disinhibition, aggression, apathy, paranoid ideas, etc.). Consequently, neither of the two classifications will guide us in establishing the degrees recognised by the scale.

This handicap remains from the previous scale, with evaluation through a score slope. We understand the importance of having variability in the score due to the need to individualise the evaluation. However, we emphasise how difficult it is to frame the unfitness in vital areas brought about by the neuropsychological sequelae within the divisions proposed in the scale according to the indications that it facilitates. A wide margin means losing objectivity and increasing the deviations among professions faced with the same evaluation, given that the assessor will score these sequelae based on experience, with significant discrepancies in the scores given. Sin embargo, we believe that the attempt of the new scale is inappropriate in trying to limit interrater variability by means of including common items that should define degree but, at times, turn out to be merely indicative. For example, an individual with damage may not fulfil all the items for one of the degrees but the clinical signs and symptoms involve maximum seriousness due to the intensity and disruptive characteristics of the problem. It should be possible to assess severe behavioural disorders that can even require long-term hospitalisation, without affecting memory, orientation and language and without involving psychotic symptoms, in and of themselves as a severe or very severe condition. Perhaps it would be more appropriate the base the degrees simply on the level of functional affectation that might exist (which is something that some of the items that we indeed consider as defining degree already do: limitations in daily activities, or in work and social areas). Such functional restrictions can currently be based on specific scales that establish a continuous slope (for example, the GAF6).

Consequently, we believe that a lesion that can be as disruptive as both official classifications show and is so complicate to grade should be handled in a scoring system without such strict ranking divisions. We propose that the current scale should be interpreted less restrictively, considering that the intensity of any of the items described is sufficient for attributing a specific degree of affectation, without the need to fulfil all the items described for the syndrome in a specific level, paying attention fundamentally to the functional problems involved.

Please cite this article as: Martí-Agustí G, Gómez-Durán EL, Vilardell-Molas J, Martí-Amengual G, Martin-Fumadó C, Arimany-Manso J. Valoración del daño corporal en el trastorno orgánico de la personalidad. Rev Psiquiatr Salud Ment (Barc.). 2017;10:59–61.