There have been controversial results in the study of gender differences in first episode psychosis (FEP). Substance abuse is the main existing comorbidity in FEP, and has been associated with worse prognosis and greater symptom severity.

ObjectivesTo explore gender differences in FEP in relation to drug abuse, and their relationship with hospital readmissions.

MethodologyDescriptive and prospective study (18 months).

ResultsWe included 141 patients (31.2% women), aged 26.1 years on average, mostly diagnosed with schizophreniform disorder (32.6%). A percentage of 58.9 had problematic use of drugs. Gender significant differences were found in age of onset, age at entry to the programme, marital status and cohabitation, and percentage differences were revealed in current drug abuse and frequency of consumption. Gender, duration of untreated psychosis, psychiatric history, age of onset and previous drug use were not predictors of re-entry. Hospital readmission rate was 24.8%, with no gender differences. The most common reasons for admission were abandonment of treatment (66.7%) and drug abuse (44.4%). Drug abuse was higher in the men than in the women as a reason for re-admission.

ConclusionsThere are gender differences in FEP. Men have an earlier onset of symptoms and have worse functional outcomes. Drug abuse in men is higher and represents a major cause of hospital readmission. Therapeutic interventions to prevent the effects of drug abuse are necessary from the early stages of the illness.

El estudio de diferencias de género en primeros episodios psicóticos (PEPs) ha aportado resultados controvertidos en los últimos años. El consumo de sustancias es la principal comorbilidad en PEPs, y se ha relacionado con un peor pronóstico y con una mayor gravedad sintomática.

ObjetivosExplorar las diferencias de género en PEPs en relación con el consumo de sustancias, así como su relación con los reingresos hospitalarios.

MetodologíaAnalítico y prospectivo (18 meses).

ResultadosIncluimos 141 pacientes (31,2% mujeres), con una edad media de 26,1 años, mayoritariamente diagnosticadas de trastorno esquizofreniforme (32,6%). Un 58,9% presentan algún consumo problemático de sustancias. Encontramos diferencias significativas de género en la edad de inicio, de ingreso en el programa, el estado civil y la convivencia, y diferencias en el consumo de sustancias actual y la frecuencia de consumo. El género, la duración de la psicosis no tratada, los antecedentes psiquiátricos, la edad de inicio o el consumo de sustancias previo no fueron factores predictores de reingreso. El porcentaje de reingreso hospitalario fue del 24,8%, sin diferencias de género. Entre los motivos más frecuentes de ingreso se encuentran el abandono del tratamiento (66,7%) y el consumo de sustancias (44,4%), siendo mayor en los hombres el consumo de sustancias como motivo de reingreso.

ConclusionesExisten diferencias de género en PEPs. Los hombres inician más tempranamente los síntomas, con peores resultados funcionales. El consumo de sustancias en hombres es mayor y representa un importante motivo de reingreso hospitalario. Intervenciones terapéuticas dirigidas a prevenir su efecto son necesarias desde las primeras fases.

The impact of mental illnesses on the European population is constantly increasing. The overall burden of neuropsychiatric disorders accounted for 18.4% of the total years of life adjusted for disability.1 In people affected by a first psychotic episode (FEPs), the first years of treatment are crucial in subsequent clinical and functional evolution. However, up to 52.0% of patients present in a poor condition at the time of starting therapeutic programmes, even specific ones. Furthermore, as high as 37% of them continue with a low functional status at completion of the programmes and even 18% of those who started with good functionality, lose this.2

During the last decade, the study of gender differences in FEPs has become a topic of interest. In fact, members of the different samples of FEPs tend to be males, with non-affective psychoses, poorer levels of premorbid adjustment, poorer education and a greater tendency to present self-reported accounts of learning difficulties, medical-legal problems, traumatic experiences and substance abuse.2 However, as Arranz et al.,3 point out, in many studies the gender variable has been used as a covariate or as a predictor in statistical analysis, and there are few studies which have considered gender as the result or central hypothesis of the study.3–10 Even so, some of the results between gender and FEPs regarding clinical and prognostic variables remain contradictory or inconsistent.11

One of the most conclusive findings regarding gender differences in psychosis and FEPs has been the age of onset, this being earlier for men,3,11,12 although other studies have not been able to corroborate this.5,9 The difference between gender and premorbid functioning has also been replicated, this being generally better among women.5,11,12 Regarding symptoms, studies that have found gender differences4,5,9,12 suggest that men have more severe negative symptoms, while women show more affective symptoms.11 Regarding the duration of untreated psychosis (DUP), although studies continue to show that men have a tendency to a longer DUP compared to women3,4,6 a review could not confirm this.13

A series of studies have analyzed gender differences in prognosis, course and evolution after FEPs, with contradictory results. It has been described that men have a poorer prognosis.5 Male gender (and the presence of negative symptoms) also predicts poorer functionality in FEPs at 2 years of follow-up.14 The observed heterogeneity of gender differences in psychotic disorder may be attributable to methodological differences between epidemiological studies (sample selection, sample size or other factors).5

Substance use is common among patients diagnosed with recent-onset psychoses and schizophrenia, and is shown to be the main comorbidity in FEPs.11 It has also been related to a worse prognosis and more serious symptoms.11

On the other hand, in the general population, several studies have reported a higher prevalence of substance abuse in men, with higher levels of comorbidity for substance use disorders.11 Men in the general population have greater comorbidity with the use of cannabis, cocaine and hallucinogens, while women may record greater abuse of anxiolytics. Nonetheless, other population studies show greater consumption in women.15 This data must be taken into account when interpreting results from clinical samples.

It is known that up to 30–60% of patients affected by FEPs relapse during the first 2 years of evolution14 and that during the first 5 years of evolution there is a higher risk of relapses and re-admissions, worsening the prognosis. There are different factors that influence these relapses and hospital readmissions. However, these have not yet been sufficiently analyzed in our environment, especially their relationship with gender.

Aims- 1.

To explore gender differences in people diagnosed with FEPs related to substance use.

- 2.

To establish the relationship between substance use by gender and hospital readmissions.

Design: analytical and prospective

Sample: patients consecutively included in the FEP Corporació Sanitària Parc Taulí programme (Sabadell) between January 2010 and October 2014. The Corporació belongs to the public network and serves a reference population of 430,000 inhabitants, mostly urban and employed in the economy, industry and services sector. This is the only hospital that treats serious mental illness in the area.

Inclusion criteria: age between 18 and 35 years, affected by any first episode with psychotic symptoms according to the DSM-IV-TR (American Psychiatric Association, 2002): schizophreniform disorder, schizophrenia (and subtypes), schizoaffective disorder (and subtypes), unspecified psychotic disorder, brief psychotic disorder, episodes of bipolar disorder (and subtypes) or major depressive disorder with psychotic symptoms. Exclusion criteria: psychosis due to medical illness as a result of the consumption of substances and patients with mental retardation. Description of the programme: the FEPs programme at the Corporació Sanitària Parc Taulí emerges as a need for specific attention to be paid to incipient psychosis with the objective, on the one hand, of early detection in all the areas of Primary and Specialized Healthcare in the area and, on the other hand, with the clinical objective of obtaining the best therapeutic results once the process has begun. Specific care is provided in both psychiatric and psychotherapeutic areas, with group and individual sessions, rehabilitation strategies and re-entry to work or education, where appropriate. Likewise, our programme has a specific section on psychoeducation and family follow-up, as well as coordinating the different levels of care and resources. As regards development and inclusion and exclusion criteria, in general the programme follows the recommendations laid down in the Development Guide of Specific Care for Incipient Psychosis produced by the Catalonian regional government.16

Instruments: a questionnaire to compile sociodemographic data and personal and family psychiatric records. The age of onset of symptoms, the DUP and the Brief Psychosis Rating Scale17 were included here. The toxicological data (personal and family) included problematic consumption contributed by the patient, the family, the clinical history, or in analytical data. The evolutionary data mainly included the date of the first hospital admission (if any) after entering the programme.

In our population, in the absence of a more consensus-based definition and taking into account both the most prevalent use of cannabis and the high frequency of associated consumption, we considered problematic consumption of any substance that produces problems for the consumer or their environment, and within these problems we would include: problems of physical or mental health, social problems and even risky behaviour that could endanger the life or health of the consumer.18

Follow-up: 18 months from entry to the programme.

Statistical analysis: descriptive and comparative according to parametric and non-parametric tests, as indicated (Student t or Mann–Whitney U for continuous variables and Chi-square or Fisher's exact test for categorical ones). Due to the exploratory nature and performance of multiple comparisons, we agreed on a significance level of less than .01.

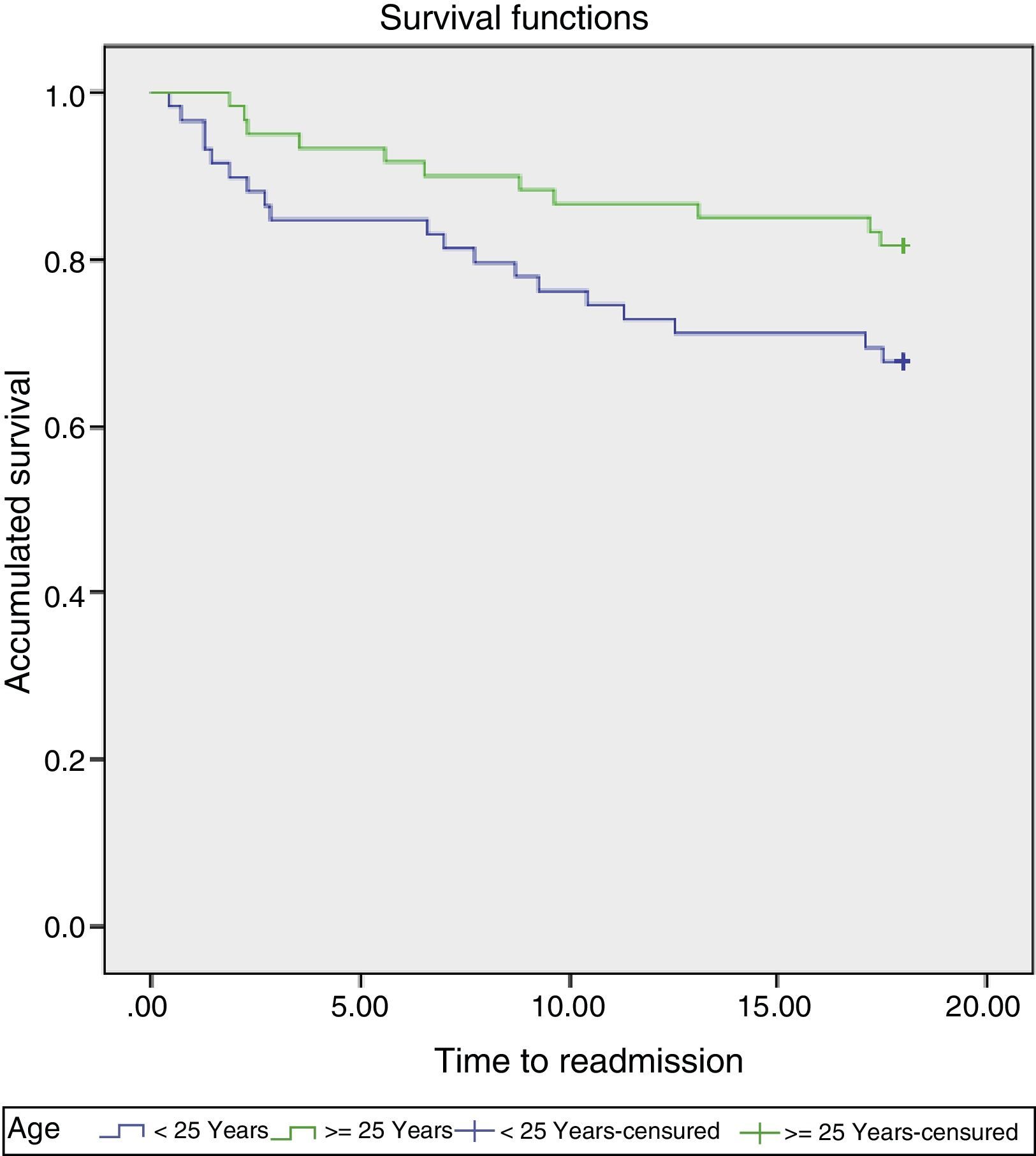

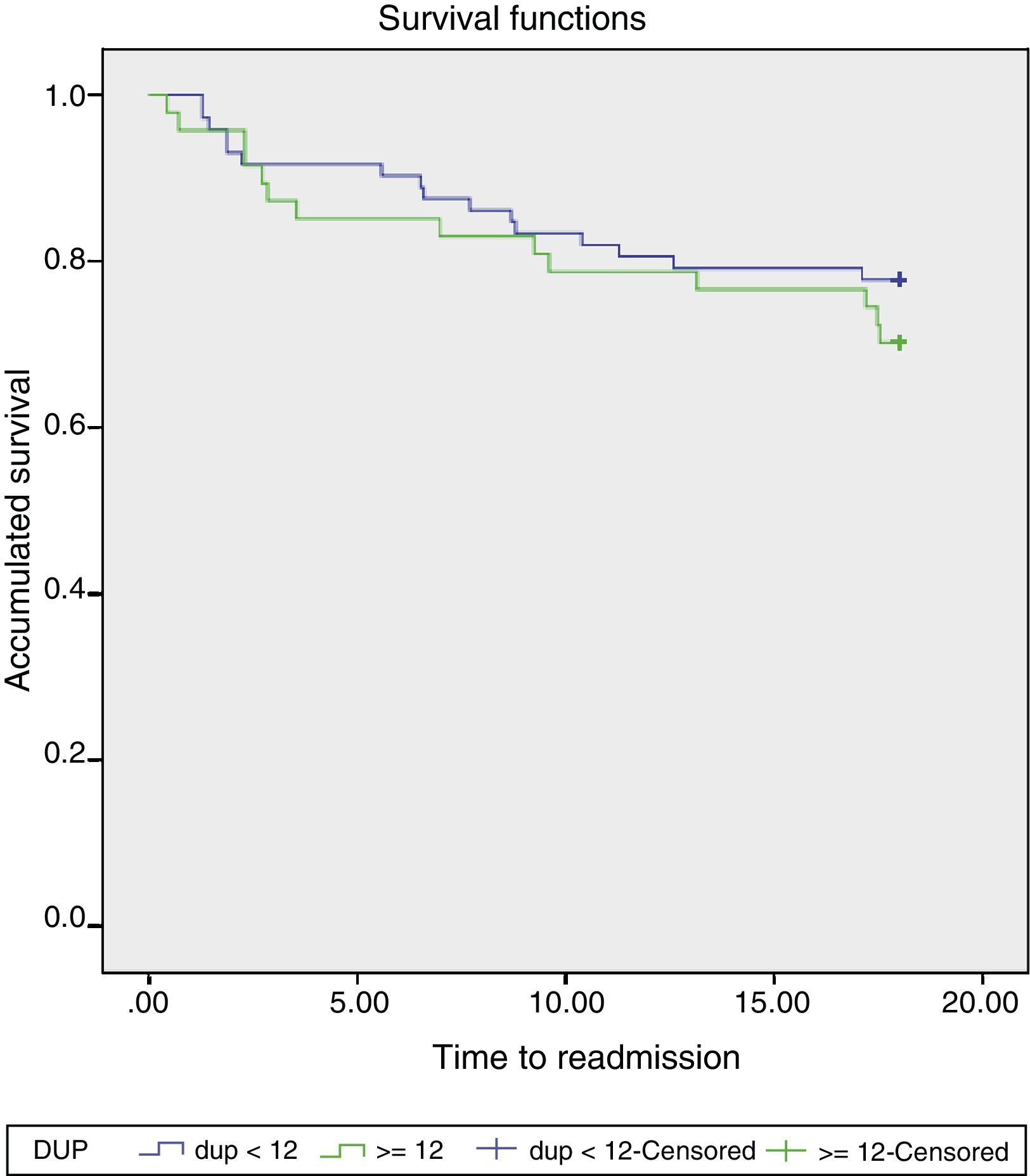

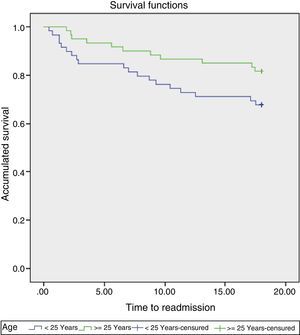

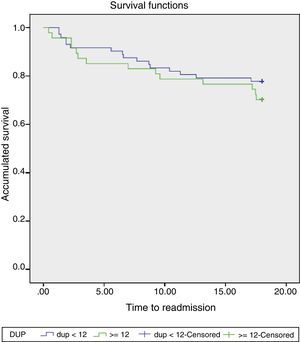

Finally, we ran Kaplan–Meier survival analysis. We considered 25 years as the cut-off age (median of our sample) for the survival analysis in relation to the age of onset (Fig. 1). For the analysis of the DUP, we considered the division, of 12 months as a cut-off point,19 as proposed by Thomas and Nandhra in 2009.

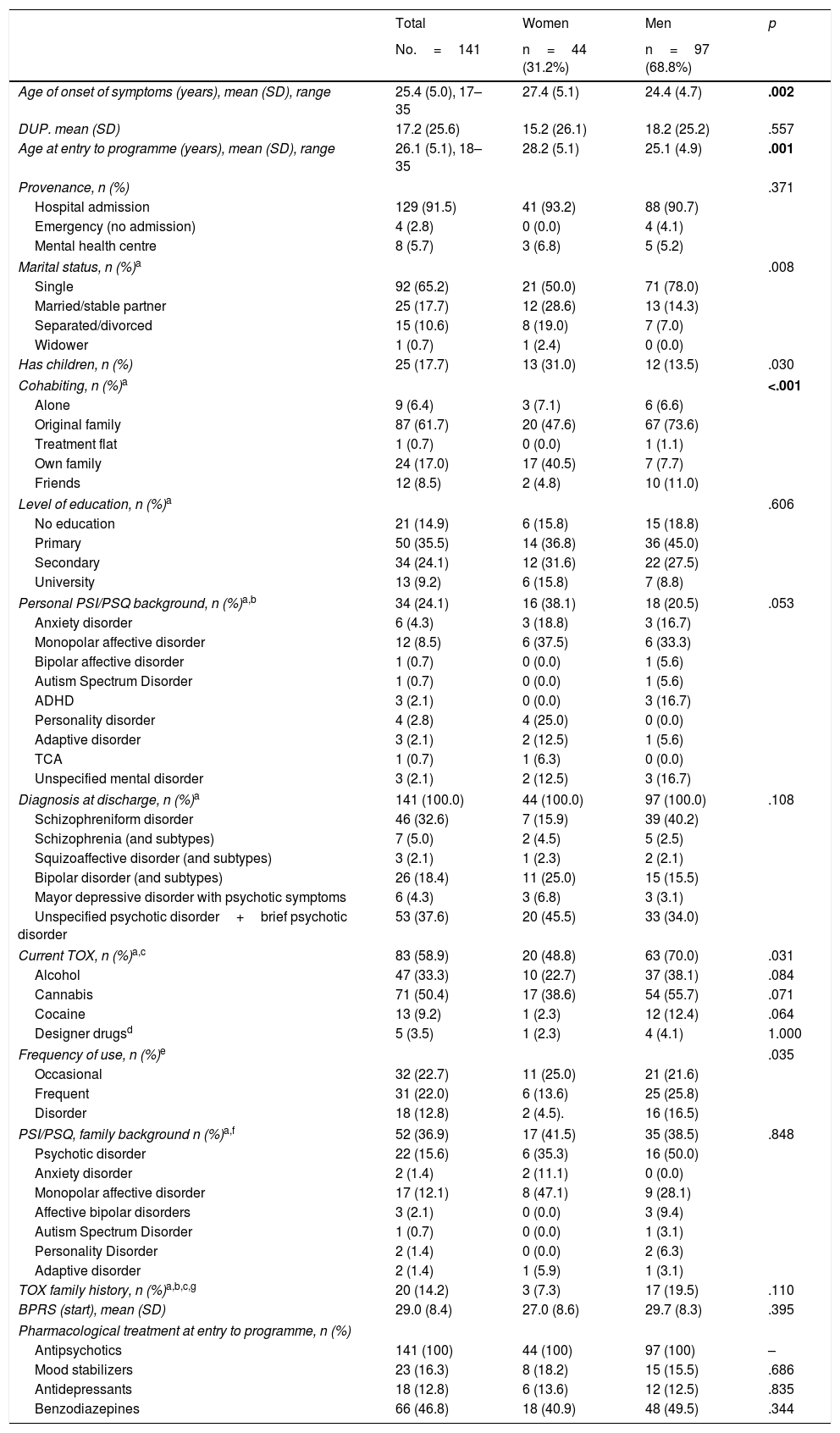

ResultsThese are summarized in Table 1: a total of 141 patients took part, with an average age of 26.1 years at the beginning of the programme. A total of 31.2% were women, 65.2% were single and 61.7% resided with their family of origin. The majority were detected in the Emergency Department and were included after a first hospital admission (91.5%). The most frequent diagnosis was schizophreniform disorder (32.6%). Up to 58.9% of patients presented some problematic use of associated substances, especially cannabis (50.4%) and alcohol (33.3%). During the 18 months of follow-up, the abandonment rate was 12%. We found gender differences in the age of onset of symptoms, the age of admission into the programme, marital status and current cohabitation (Table 1). We also found a greater tendency towards significance in terms of current substance consumption and the frequency of consumption in women. Gender, DUP, personal or family psychiatric history, age at onset or substance use prior to the start of the programme did not show up as predictors of readmission (Table 2). Nor did the diagnoses influence hospital admissions after entering the programme. A rate of 24.8% of hospital readmissions was recorded during the 18 months of follow-up, without gender differences (Table 2). Among the most frequent reasons for admission were the abandonment of treatment (66.7%) and the consumption of substances (44.4%). There was a tendency to significance in terms of substance consumption as the reason for readmission, this being higher in men.

Characteristics of the sample (n=141).

| Total | Women | Men | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No.=141 | n=44 (31.2%) | n=97 (68.8%) | ||

| Age of onset of symptoms (years), mean (SD), range | 25.4 (5.0), 17–35 | 27.4 (5.1) | 24.4 (4.7) | .002 |

| DUP. mean (SD) | 17.2 (25.6) | 15.2 (26.1) | 18.2 (25.2) | .557 |

| Age at entry to programme (years), mean (SD), range | 26.1 (5.1), 18–35 | 28.2 (5.1) | 25.1 (4.9) | .001 |

| Provenance, n (%) | .371 | |||

| Hospital admission | 129 (91.5) | 41 (93.2) | 88 (90.7) | |

| Emergency (no admission) | 4 (2.8) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (4.1) | |

| Mental health centre | 8 (5.7) | 3 (6.8) | 5 (5.2) | |

| Marital status, n (%)a | .008 | |||

| Single | 92 (65.2) | 21 (50.0) | 71 (78.0) | |

| Married/stable partner | 25 (17.7) | 12 (28.6) | 13 (14.3) | |

| Separated/divorced | 15 (10.6) | 8 (19.0) | 7 (7.0) | |

| Widower | 1 (0.7) | 1 (2.4) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Has children, n (%) | 25 (17.7) | 13 (31.0) | 12 (13.5) | .030 |

| Cohabiting, n (%)a | <.001 | |||

| Alone | 9 (6.4) | 3 (7.1) | 6 (6.6) | |

| Original family | 87 (61.7) | 20 (47.6) | 67 (73.6) | |

| Treatment flat | 1 (0.7) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.1) | |

| Own family | 24 (17.0) | 17 (40.5) | 7 (7.7) | |

| Friends | 12 (8.5) | 2 (4.8) | 10 (11.0) | |

| Level of education, n (%)a | .606 | |||

| No education | 21 (14.9) | 6 (15.8) | 15 (18.8) | |

| Primary | 50 (35.5) | 14 (36.8) | 36 (45.0) | |

| Secondary | 34 (24.1) | 12 (31.6) | 22 (27.5) | |

| University | 13 (9.2) | 6 (15.8) | 7 (8.8) | |

| Personal PSI/PSQ background, n (%)a,b | 34 (24.1) | 16 (38.1) | 18 (20.5) | .053 |

| Anxiety disorder | 6 (4.3) | 3 (18.8) | 3 (16.7) | |

| Monopolar affective disorder | 12 (8.5) | 6 (37.5) | 6 (33.3) | |

| Bipolar affective disorder | 1 (0.7) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (5.6) | |

| Autism Spectrum Disorder | 1 (0.7) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (5.6) | |

| ADHD | 3 (2.1) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (16.7) | |

| Personality disorder | 4 (2.8) | 4 (25.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Adaptive disorder | 3 (2.1) | 2 (12.5) | 1 (5.6) | |

| TCA | 1 (0.7) | 1 (6.3) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Unspecified mental disorder | 3 (2.1) | 2 (12.5) | 3 (16.7) | |

| Diagnosis at discharge, n (%)a | 141 (100.0) | 44 (100.0) | 97 (100.0) | .108 |

| Schizophreniform disorder | 46 (32.6) | 7 (15.9) | 39 (40.2) | |

| Schizophrenia (and subtypes) | 7 (5.0) | 2 (4.5) | 5 (2.5) | |

| Squizoaffective disorder (and subtypes) | 3 (2.1) | 1 (2.3) | 2 (2.1) | |

| Bipolar disorder (and subtypes) | 26 (18.4) | 11 (25.0) | 15 (15.5) | |

| Mayor depressive disorder with psychotic symptoms | 6 (4.3) | 3 (6.8) | 3 (3.1) | |

| Unspecified psychotic disorder+brief psychotic disorder | 53 (37.6) | 20 (45.5) | 33 (34.0) | |

| Current TOX, n (%)a,c | 83 (58.9) | 20 (48.8) | 63 (70.0) | .031 |

| Alcohol | 47 (33.3) | 10 (22.7) | 37 (38.1) | .084 |

| Cannabis | 71 (50.4) | 17 (38.6) | 54 (55.7) | .071 |

| Cocaine | 13 (9.2) | 1 (2.3) | 12 (12.4) | .064 |

| Designer drugsd | 5 (3.5) | 1 (2.3) | 4 (4.1) | 1.000 |

| Frequency of use, n (%)e | .035 | |||

| Occasional | 32 (22.7) | 11 (25.0) | 21 (21.6) | |

| Frequent | 31 (22.0) | 6 (13.6) | 25 (25.8) | |

| Disorder | 18 (12.8) | 2 (4.5). | 16 (16.5) | |

| PSI/PSQ, family background n (%)a,f | 52 (36.9) | 17 (41.5) | 35 (38.5) | .848 |

| Psychotic disorder | 22 (15.6) | 6 (35.3) | 16 (50.0) | |

| Anxiety disorder | 2 (1.4) | 2 (11.1) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Monopolar affective disorder | 17 (12.1) | 8 (47.1) | 9 (28.1) | |

| Affective bipolar disorders | 3 (2.1) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (9.4) | |

| Autism Spectrum Disorder | 1 (0.7) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (3.1) | |

| Personality Disorder | 2 (1.4) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (6.3) | |

| Adaptive disorder | 2 (1.4) | 1 (5.9) | 1 (3.1) | |

| TOX family history, n (%)a,b,c,g | 20 (14.2) | 3 (7.3) | 17 (19.5) | .110 |

| BPRS (start), mean (SD) | 29.0 (8.4) | 27.0 (8.6) | 29.7 (8.3) | .395 |

| Pharmacological treatment at entry to programme, n (%) | ||||

| Antipsychotics | 141 (100) | 44 (100) | 97 (100) | – |

| Mood stabilizers | 23 (16.3) | 8 (18.2) | 15 (15.5) | .686 |

| Antidepressants | 18 (12.8) | 6 (13.6) | 12 (12.5) | .835 |

| Benzodiazepines | 66 (46.8) | 18 (40.9) | 48 (49.5) | .344 |

BPRS (start): Brief Psychosis Rating Scale at start of first admission. SD: standard deviation; DUP: duration in weeks of untreated psychosis, before the first admission; ED: eating disorder; ADHD: attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder; ASD: autism spectrum disorders.

Psychological and psychiatric history of the patient prior to admission at first psychotic episode.

Excessive/problematic use of substances (some patients consume more than one or two problematic substances).

The consumption of toxic substances on entry to the programme includes patients with occasional consumption (intermittent use of the substance(s), without a fixed pattern and with long intervals of abstinence), frequent (habitual) and of substance consumption disorder, which includes patients with substance abuse or dependence according to the DSM-IV-TR criteria (American Psychiatric Association, 2002).

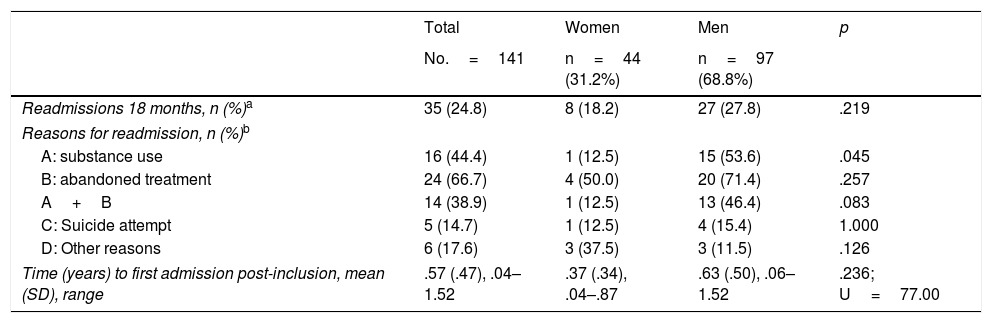

Characteristics of readmissions.

| Total | Women | Men | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No.=141 | n=44 (31.2%) | n=97 (68.8%) | ||

| Readmissions 18 months, n (%)a | 35 (24.8) | 8 (18.2) | 27 (27.8) | .219 |

| Reasons for readmission, n (%)b | ||||

| A: substance use | 16 (44.4) | 1 (12.5) | 15 (53.6) | .045 |

| B: abandoned treatment | 24 (66.7) | 4 (50.0) | 20 (71.4) | .257 |

| A+B | 14 (38.9) | 1 (12.5) | 13 (46.4) | .083 |

| C: Suicide attempt | 5 (14.7) | 1 (12.5) | 4 (15.4) | 1.000 |

| D: Other reasons | 6 (17.6) | 3 (37.5) | 3 (11.5) | .126 |

| Time (years) to first admission post-inclusion, mean (SD), range | .57 (.47), .04–1.52 | .37 (.34), .04–.87 | .63 (.50), .06–1.52 | .236; U=77.00 |

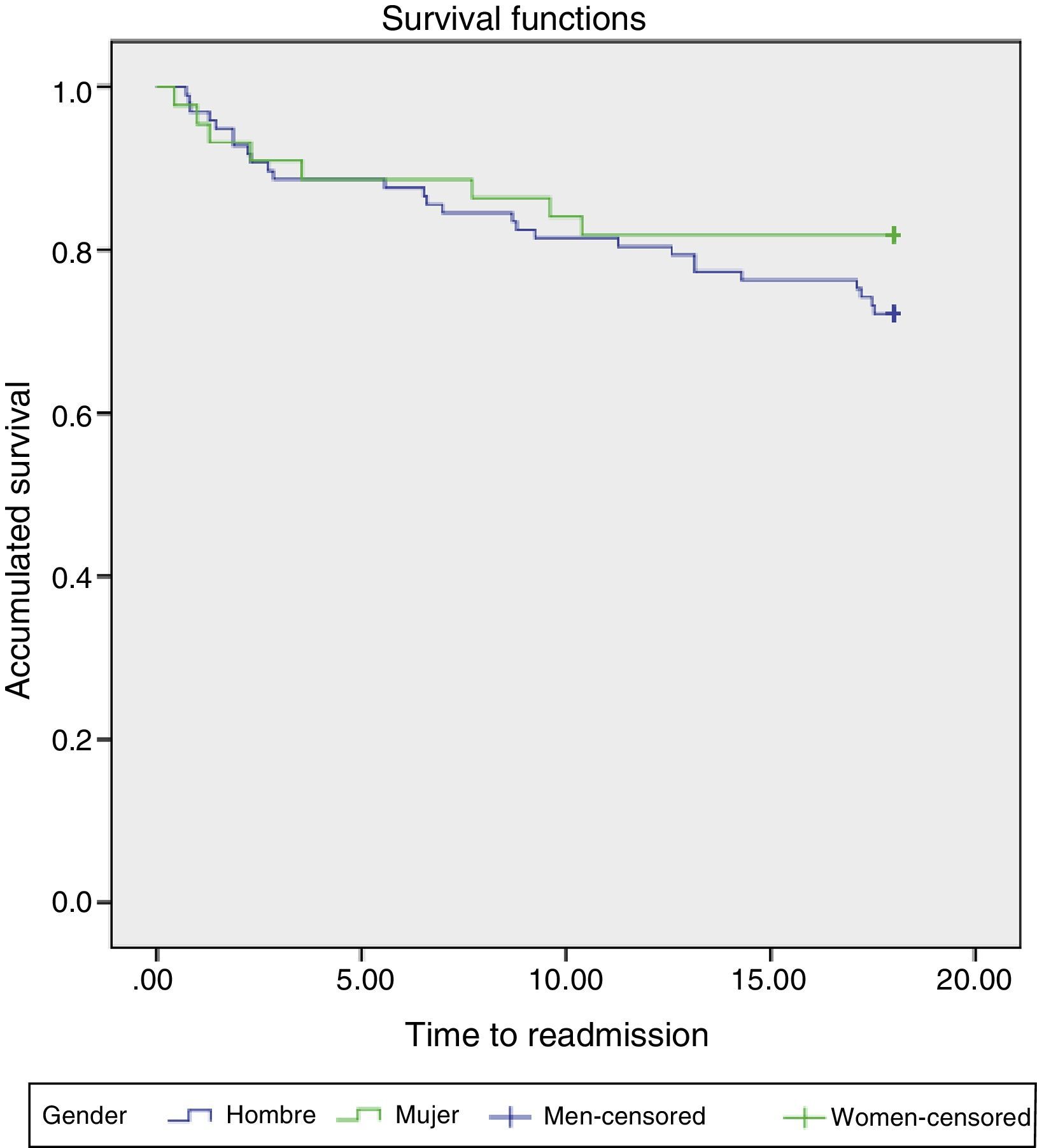

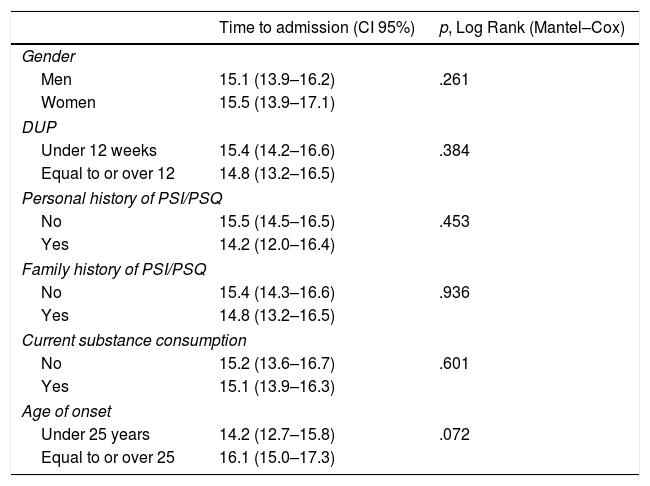

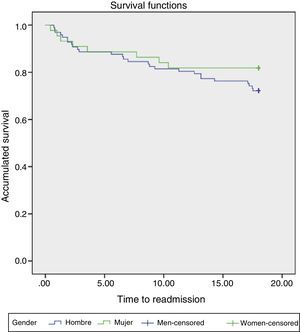

In the Kaplan–Meier survival analysis, as shown in Table 3, gender and other factors analyzed did not result in a differential impact for the time of patients’ admission during the follow-up period. Fig. 2 shows the survival analysis by gender, where we found no differences. Fig. 3 shows the survival analysis by DUP while Fig. 1 shows the survival analysis in relation to the age of onset.

Kaplan–Meier survival analysis.

| Time to admission (CI 95%) | p, Log Rank (Mantel–Cox) | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Men | 15.1 (13.9–16.2) | .261 |

| Women | 15.5 (13.9–17.1) | |

| DUP | ||

| Under 12 weeks | 15.4 (14.2–16.6) | .384 |

| Equal to or over 12 | 14.8 (13.2–16.5) | |

| Personal history of PSI/PSQ | ||

| No | 15.5 (14.5–16.5) | .453 |

| Yes | 14.2 (12.0–16.4) | |

| Family history of PSI/PSQ | ||

| No | 15.4 (14.3–16.6) | .936 |

| Yes | 14.8 (13.2–16.5) | |

| Current substance consumption | ||

| No | 15.2 (13.6–16.7) | .601 |

| Yes | 15.1 (13.9–16.3) | |

| Age of onset | ||

| Under 25 years | 14.2 (12.7–15.8) | .072 |

| Equal to or over 25 | 16.1 (15.0–17.3) | |

DUP: duration of untreated psychosis; CI 95%: confidence interval of 95%; PSI/PSQ: psychological/psychiatric history.

Considering 25 years as the cut-off age (median of our sample), the analysis on survival in relation to the age of onset (Fig. 1), although not significant either, confirms more rapid admission in patients who began substance abuse at a younger age (below or equal to 25 years).

DiscussionTo our knowledge, this is the first analysis in our environment that explores gender differences as the reason for hospital readmission in patients with FEPs. Our results confirm some previous ones in terms of gender differences in psychosis, such as a younger age at onset in men3,4,9,12,13,20,21 and greater difficulties with independent cohabitation also in men.5,9 As in other studies, we did not find gender differences in DUP,6–9,13 on the Brief Psychosis Rating Scale at entry to the programme,21 or in the clinical diagnosis when starting the programme,12 among other variables in the study.

However, our results show that maintaining consumption of substances was one of the main causes of re-admission, as was also shown by the review and meta-analysis by Alvarez-Jimenez et al.22 with a possible gender effect.

Substance use was very prevalent among people affected by FEPs, with different results depending on the samples.23–25 For example, the study by Wade et al.23 with 103 FEPs recorded at 3 mental health centres and followed up for 15 months, showed how substance abuse was independently related to an increased risk of readmission, relapses in positive symptoms, and a shorter time of relapse for positive symptoms. In the same direction, the study by Arranz et al.3 and others5,9,26 show how men consumed more substances in general and to a significant extent. In our sample, no significant differences were found, although men consumed more substances in percentage terms. Among the possible explanations for these differences were the characteristics of the sample itself, the assessment instruments, or effects arising from changes in the general population as regards the consumption of substances.

In this sense, currently, according to the Government Delegation for the National Plan on Drugs,27 the main legal substance consumed among Spanish women is alcohol, followed by tobacco and cannabis. Nonetheless, there has been a worrying increase in cocaine use and tranquilizers and hypnosedatives. Similarly, although epidemiological samples still detect a higher prevalence of alcohol and other drug abuse among men, as compared to women, an increase in prevalence has also been observed among women.28

There is some evidence of greater severity in cocaine addiction in women.29 In fact, in samples of young Americans, the proportion of young women with cocaine dependence is higher than among young men (p<.01).28 However, this North American data is not replicated in our adolescent and youth population.27 Regarding cannabis, in Spain this continues to be the most widely consumed illegal substance, affecting 13.6% of men as compared to 5.5% of women. Fortunately, however, there has been a decrease in consumption for both sexes as compared with the 2009 figures.27 The problem is that its use is widely and socially accepted in general and, unfortunately, in the case of women, consumption has grown since the first statistics.30

The high prevalence of substance use found in our sample of patients is in agreement with the overall percentages found in previous studies3,5,6 ranging from 68–80% in men and 30–51% in women.

Regarding the percentages of readmissions in our sample, these were similar to rates observed in other follow-up studies at 18 months and are in agreement with other previously reported results, ranging from 24–36% of relapses at 18 months.22

Although some studies5 have reported that men are more likely to have one or more hospitalizations during follow-up at 18 months, we did not find gender differences in the percentage of readmissions. Therefore, it seems that gender is not a predictor of future readmissions.

In our study, gender was not shown as a predictor of readmission, as in previous studies.22,31 Nor did DUP or other initial variables, or even intake of substances before entry to the programme show themselves to be predictors. This indicates the importance of other factors but also the need to maintain substance abstinence in these early stages of the illness. As regards the influence of substance use on re-admission percentages, our results showed trends towards a gender differential effect that should be explored more thoroughly in the future. Likewise, the moderating impact of gender on other relapse factors should also be explored, such as lack of adherence to treatment15 or lack of insight.12 In fact, advances in the treatment of our patients must take into account a much more personalized and targeted approach, with special attention to therapeutic aspects32 but also to the specific ones related to gender.

Limitations and strong points of the studyThe main limitations of the study are the absence of systematic analytical determinations of substances and the geographically-bound characteristics of the sample. As main strengths, the adequacy of the sample, since our programme is the only service provider in the area, as well as covering specific analysis of hospital readmissions, not only of relapses, following psychometric criteria.

ConclusionsThere are gender differences in FEPs. Men manifest symptoms earlier and may at that point present poorer functional results. The rate of substance use is higher in men and it is also a key reason for hospital readmission.

Interventions aimed at alleviating (and preventing) the effects of substance use in people affected by FEPs are necessary from the early stages of treatment.

Ethical responsibilitiesProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments have been conducted on humans or animals for this research.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols laid down by their work centre on the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient information appears in this article.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflict of interest.

Please cite this article as: Crosas JM, Cobo J, Ahuir M, Hernández C, García R, Pousa E, et al. Consumo de sustancias y diferencias de género en personas afectas de un primer episodio psicótico: impacto en los porcentajes de reingreso. Rev Psiquiatr Salud Ment (Barc). 2018;11:27–35.