Cardiovascular and metabolic monitoring of patients on antipsychotic medication is essential. This becomes more important in those of paediatric age, as they are more vulnerable, and also because prescriptions of this kind of drugs are still increasing.

AimTo evaluate the monitoring of cardiovascular and metabolic risk factors in a group of children and young people on antipsychotic medication.

MethodA descriptive cross-sectional study was conducted in which a group of 220 patients aged 8–17 years, diagnosed with a mental disorder and on antipsychotic treatment. They were compared to a control group of 199 asthmatic patients not exposed to antipsychotic drugs. Data was extracted from the computerized clinical history ECAP in 2013.

ResultsThe mean age of the children was 12 years (8–17). Risperidone (67%) was the most frequent treatment. The recording of body mass index (BMI) and blood pressure (AP) was 50% in Mental Disorder (MD) patients. A higher number of cardiovascular monitoring physical parameters (weight, height, BMI and BP) were observed in the MD group compared to the control Asthma control group. Altogether, more physical parameters than biochemistry parameters were recorded.

ConclusionsThis study shows that the recording of cardiovascular parameters and metabolic studies needs to be improved in children and adolescents on treatment with antipsychotics.

El control cardiovascular y metabólico en pacientes que toman antipsicóticos es fundamental y adquiere una especial relevancia en la edad pediátrica, por ser pacientes más vulnerables y porque cada vez se prescriben fármacos de este tipo en más ocasiones.

ObjetivoDescribir el grado de cumplimiento de las recomendaciones de control de parámetros cardiovasculares y metabólicos en un grupo de niños y jóvenes en tratamiento antipsicótico.

MétodoSe trata de un estudio descriptivo transversal en el que se comparan un grupo de 220 pacientes de 8-17 años, diagnosticados de trastorno mental (TM) y en tratamiento antipsicótico, con otro grupo de referencia constituido por 199 individuos asmáticos no expuestos a antipsicóticos del mismo grupo de edad. Los datos se extrajeron de la historia clínica informatizada ECAP en el año 2013.

ResultadosLa edad de los niños se sitúa entre los 8 y 17 años. La media de edad es de 12 años. La risperidona es el antipsicótico pautado más frecuentemente (62,7%).

El porcentaje de registro de peso, talla, índice de masa corporal (IMC) y presión arterial (PA) es de aproximadamente un 50% en los pacientes del grupo TM. En el grupo TM se observa un mayor registro de los parámetros físicos de control cardiovascular (peso, talla, IMC y PA) en comparación con el grupo Asma. En conjunto, se registran más los parámetros físicos que los parámetros bioquímicos.

ConclusionesEste estudio evidencia la necesidad de seguir insistiendo en la monitorización de los parámetros cardiovasculares y metabólicos en los niños y jóvenes en tratamiento con antipsicóticos.

In recent years the prescription of antipsychotics (especially second generation) for Spanish children and adolescents has increased. The hypotheses that justify this increase are many and varied: efficacy in resolving aggression and irritability type symptoms; limitations in the alternative treatment therapies available; the recommendation of second generation antipsychotics in the clinical guidelines; and off label use.1–4 These drugs can give rise to long-term side effects that must be taken into account, especially in the paediatric population, as this is a more vulnerable group.5

Taking antipsychotics, mainly second generation, has been associated with an increased risk of developing metabolic syndrome and long-term cardiovascular problems.6 In children, this has been consistently associated with an increase in weight and body mass index (BMI),7 with an increase in prolactin levels and, in some cases, glycaemic and lipidemic disorders.8 In addition, changes in development of sex organs and a delay in sexual maturity related to hormonal alterations have been described in children.8 The pathophysiological basis of these processes is still poorly understood, and for this reason studies and precautionary measures are required to avoid them.8,9

In the child and adolescent population, clinical guidelines10 recommend that all patients taking antipsychotics should be followed up. In clinical practice in our environment, the extent to which the side effects of these drugs are monitored is not sufficiently known. Obtaining this information would be the first step to taking action aimed at detecting and preventing the increase in cardiovascular and metabolic risk involved in taking antipsychotics.

The objectives of this study are:

- (a)

To describe the sociodemographic characteristics of a group of children and adolescents in Barcelona on active antipsychotic treatment in 2013, and determine which mental disorder (MD) and antipsychotic drug has been most frequently recorded.

- (b)

To analyze the degree of follow-up care and monitoring arising from registering a series of physical and biochemical parameters for cardiovascular and metabolic risk in this group of children and adolescents.

- (c)

To compare the follow-up on this group of children and adolescents diagnosed with MD, and on antipsychotic treatment, with that of a group of children and adolescents diagnosed with another long-term disease (asthma) and not exposed to antipsychotics.

A cross-sectional descriptive study was carried out where a group of paediatric patients diagnosed with MD and under active antipsychotic treatment in 2013 (TM group) was analyzed. As we wished to assess the recording of cardiovascular and metabolic risk factors (CVRF-M) in children taking antipsychotics as compared to children who did not, a comparison group of patients who did not take these medications was looked for, and it was decided to set this up in a group of asthmatic children (Asthma group).

ContextThe population studied (MD group and Asthma group) were patients aged 8–17 years assigned to the Coastal Primary Health Service PHS (Servicio de Atención Primaria del Litoral: PHS Litoral) in the city of Barcelona (this is the catchment area for the Hospital del Mar). This primary healthcare service consists of different Primary Health Care Teams (PHTs) and Child and Juvenile Mental Health Centres (CJMHC), which were the ones that served the two populations in this study. The PHTs are teams of paediatricians and nursing staff, and are usually the first level of detection of mental health problems. They carry out coordinated activities through their specific CJMHC. Both teams use the same computer-based clinical station and can record the different indicators to be monitored. At the CJMHC, the patients taking psychotropic drugs are monitored by psychiatrists and nurses jointly. The present study was based on the data recorded by these medical services (PHTs and CJMHCs) over the course of 2013.

The CJMHC (run by the Parc de Salut Mar) and the PHT (run by the Institut Català de la Salut) associated with the PHS Litoral are: CJMHC Clot, CJMHC Ramon Turró, CJMHC La Mina, CJMHC Sant Martí and CJMHC Ciutat Vella; PHT Casc Antic, PHT Gòtic, PHT Raval Sud, PHT Raval Nord, PHT Ramon Turró, PHT Poble Nou, PHT Sant Martí Nord, PHT Sant Martí Sud, PHT La Pau, PHT Besòs, PHT El Clot and PHT La Mina/Sant Adrià of Besòs. This referral sector covers a population of 57,668 inhabitants under the age of 18.

ParticipantsThe primary healthcare clinical station's (PHCS) computerized clinical history programme was used to retrospectively identify the members of the MD group and the Asthma group. The criteria for setting up the MD group were: patients between 8 and 17 years old assigned to the Litoral PHS, diagnosed with MD and under treatment with antipsychotic drugs in 2013. The psychiatric diagnosis was reached following the diagnostic criteria within the Manual diagnóstico and estadístico de trastornos mentales (Diagnostic Manual and Statistics on Mental Disorders) in its fourth edition (DSM-IV).11 All patients who met these criteria were selected. To set up the Asthma group, a simple random sample of the total of 1449 asthmatic children was selected, between 8 and 17 years old and assigned to the PHS Litoral.

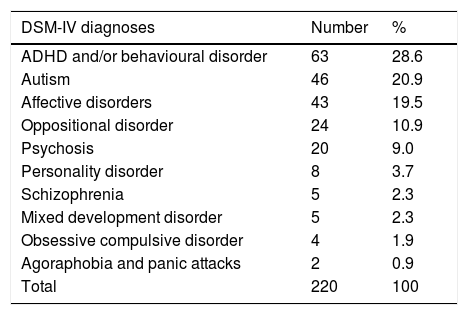

VariablesThe universal variables that were considered in this study were age and sex. The dependent variables were the frequency of visits to a PHT and/or CJMHC and the frequency with which the following physical assessment parameters were recorded in 2013: weight, height, BMI, systolic blood pressure (SBP), diastolic blood pressure (DBP), abdominal girth (ABG) and biochemical assessment (glycaemia, total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, HDL cholesterol and triglycerides). Parameter which had been recorded only once during 2013 were considered as positive recordings. The psychiatric diagnoses of the MD group patients (Table 1) and the psychotropic drugs they had prescribed were also analyzed.

Diagnoses of patients with MD.

| DSM-IV diagnoses | Number | % |

|---|---|---|

| ADHD and/or behavioural disorder | 63 | 28.6 |

| Autism | 46 | 20.9 |

| Affective disorders | 43 | 19.5 |

| Oppositional disorder | 24 | 10.9 |

| Psychosis | 20 | 9.0 |

| Personality disorder | 8 | 3.7 |

| Schizophrenia | 5 | 2.3 |

| Mixed development disorder | 5 | 2.3 |

| Obsessive compulsive disorder | 4 | 1.9 |

| Agoraphobia and panic attacks | 2 | 0.9 |

| Total | 220 | 100 |

The PHCS was used to identify the number of patients visited in each group (MD and Asthma) during 2013, and to ascertain how many of them had recorded cardiovascular and metabolic control parameters. For each recorded parameter, its quantitative value was identified. The most frequent psychiatric diagnoses in the MT group, and the psychotropic drugs that were prescribed, were also determined from the PHCS. In order to carry out this study, current legislation and protocols laid down were abided by for access to the data in the patients’ medical records. The study was discussed and approved by the ethics committee on clinical research at the Hospital del Mar Institute of Medical Research (IMIM in its Spanish acronym).

Statistical methodsA descriptive analysis of the sample was run using percentages for the qualitative variables and means, means and standard deviation (SD) for the quantitative variables. A comparative analysis of the population being treated with antipsychotics was run to compare the population with asthma. For the comparison of qualitative variables between the 2 groups, chi-square and Fisher's exact test were used. For the comparison of quantitative variables Student's t was used and, if the quantitative variable did not follow a normal distribution in any of the groups to be compared, the nonparametric Mann–Whitney test was used. p=.05 was considered the limit of statistical significance.

ResultsThe total number of patients on antipsychotic treatment was 220 children and adolescents. The group to be compared was the result of simple randomization of 1449 asthmatic children, obtaining the sample of 199 patients with asthma.

Characteristics of the group with mental disorderThe children were aged between 8 and 17 years old. The mean age was 12 years.

The most frequent psychiatric diagnoses in patients in the group with mental disorder (MD) (Table 1) were attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) with behavioural disorder, autistic spectrum disorders (ASD) and affective disorders. (Unipolar and bipolar affective disorders were included).

The most frequently prescribed antipsychotic drugs were Risperidone (62.7%), which stood out above all, followed by Aripiprazole (26.8%), Paliperidone (6.4%) and Quetiapine (5.9%).

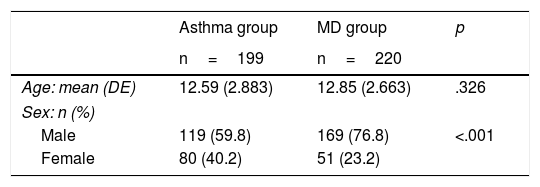

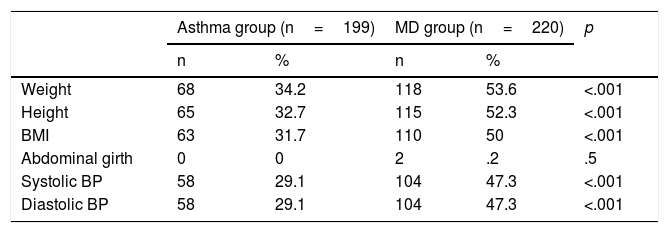

Comparison of the group with mental disorder and the group with asthmaTable 2 shows the socio-demographic features of the 2 groups. With regard to sex, there were more males than females in each group, particularly the group with mental disorders (76.8% males and 23.2% females). In the group with mental disorder, a greater extent of recording the physical parameters of cardiovascular control (weight, height, BMI, BP) was observed in comparison with the Asthma group (Table 3). The percentage of weight, height, BMI and BP recorded was approximately 50% in patients in the MD group, and approximately 30% in the Asthma group. As for the ABG, this was scarcely recorded in any of the groups.

Recording of physical assessment parameters.

| Asthma group (n=199) | MD group (n=220) | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Weight | 68 | 34.2 | 118 | 53.6 | <.001 |

| Height | 65 | 32.7 | 115 | 52.3 | <.001 |

| BMI | 63 | 31.7 | 110 | 50 | <.001 |

| Abdominal girth | 0 | 0 | 2 | .2 | .5 |

| Systolic BP | 58 | 29.1 | 104 | 47.3 | <.001 |

| Diastolic BP | 58 | 29.1 | 104 | 47.3 | <.001 |

| Group age 8–14 | Asthma group (n=133) | MD group (n=155) | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Weight | 59 | 44.4 | 88 | 56.8 | .036 |

| Height | 57 | 42.9 | 88 | 56.8 | .019 |

| BMI | 55 | 41.4 | 82 | 52.9 | .050 |

| Abdominal girth | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1.3 | .189 |

| Systolic BP | 44 | 33.1 | 75 | 48.4 | .009 |

| Diastolic BP | 44 | 33.1 | 76 | 49.0 | .006 |

| Group age 15–17 | Asthma group (n=66) | MD group (n=65) | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Weight | 9 | 13.6 | 30 | 46.2 | <.001 |

| Height | 8 | 12.1 | 27 | 41.5 | <.001 |

| BMI | 8 | 12.1 | 28 | 43.1 | <.001 |

| Abdominal girth | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Systolic BP | 14 | 21.2 | 29 | 44.6 | .004 |

| Diastolic BP | 14 | 21.2 | 28 | 43.1 | .007 |

BMI: body mass index; BP: blood pressure; MD: mental disorder.

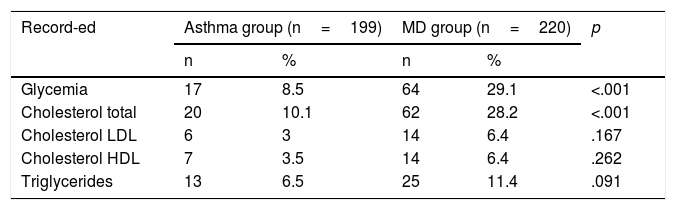

Regarding biochemical parameters (Table 4), a greater degree of recording was also observed in the MD group as compared with the Asthma group. Within these parameters, glycaemia was registered to a significant extent.

Recording of biochemical parameters.

| Record-ed | Asthma group (n=199) | MD group (n=220) | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Glycemia | 17 | 8.5 | 64 | 29.1 | <.001 |

| Cholesterol total | 20 | 10.1 | 62 | 28.2 | <.001 |

| Cholesterol LDL | 6 | 3 | 14 | 6.4 | .167 |

| Cholesterol HDL | 7 | 3.5 | 14 | 6.4 | .262 |

| Triglycerides | 13 | 6.5 | 25 | 11.4 | .091 |

| Group age 8–14 | Asthma group (n=133) | MD group (n=155) | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Glycemia | 10 | 7.5 | 42 | 27.1 | <.001 |

| Cholesterol Total | 12 | 9.0 | 40 | 25.8 | <.001 |

| LDL Cholesterol | 4 | 3.0 | 8 | 5.2 | .395 |

| HDL Cholesterol | 5 | 3.8 | 8 | 5.2 | .777 |

| Triglycerides | 9 | 6.8 | 17 | 11.0 | .302 |

| Group age 15–17 | Asthma group (n=66) | MD group (n=65) | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Glycemia | 7 | 10.6 | 22 | 33.8 | .002 |

| Cholesterol Total | 8 | 12.1 | 33.8 | .004 | |

| Cholesterol LDL | 2 | 3.0 | 6 | 9.2 | .164 |

| Cholesterol HDL | 2 | 3.0 | 6 | 9.2 | .164 |

| Triglycerides | 4 | 6.1 | 8 | 12.3 | .242 |

HDL: high density lipoprotein; LDL: low density lipoprotein; MD: mental disorder.

Together, the physical parameters were recorded more than the biochemical ones.

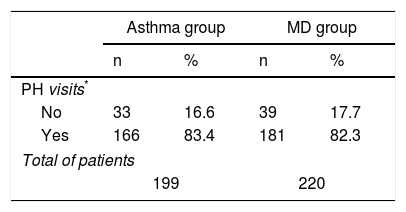

Regarding monitoring these patients in the surgery, it was observed that the children in the MD group were attended in primary care with a similar frequency to the children in the Asthma group (Table 5).

Primary healthcare visits.

| Asthma group | MD group | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | |

| PH visits* | ||||

| No | 33 | 16.6 | 39 | 17.7 |

| Yes | 166 | 83.4 | 181 | 82.3 |

| Total of patients | ||||

| 199 | 220 | |||

PH: primary healthcare.

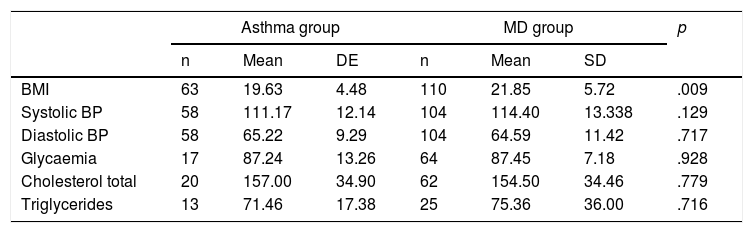

Finally, comparing the mean values of the cardiovascular control parameters, the mean BMI was significantly higher in the MD group, this being 21.8 in the MD group vs 19.6 in the Asthma group (Table 6).

Weighted averages of the physical and biochemical assessment parameters.

| Asthma group | MD group | p | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Mean | DE | n | Mean | SD | ||

| BMI | 63 | 19.63 | 4.48 | 110 | 21.85 | 5.72 | .009 |

| Systolic BP | 58 | 111.17 | 12.14 | 104 | 114.40 | 13.338 | .129 |

| Diastolic BP | 58 | 65.22 | 9.29 | 104 | 64.59 | 11.42 | .717 |

| Glycaemia | 17 | 87.24 | 13.26 | 64 | 87.45 | 7.18 | .928 |

| Cholesterol total | 20 | 157.00 | 34.90 | 62 | 154.50 | 34.46 | .779 |

| Triglycerides | 13 | 71.46 | 17.38 | 25 | 75.36 | 36.00 | .716 |

Mean: weighted average of values for all patients in the group.

SD: standard deviation; BMI: body mass index; BP: blood pressure

Early detection of side effects in antipsychotic treatments in children and adolescents is relevant and necessary to prevent the impact of short and long-term side effects, such as obesity and metabolic syndrome.

In this article we obtained recorded data for metabolic syndrome risk factors and the use of antipsychotics in children and adolescents under treatment with these drugs, with the main objective of assessing the degree of compliance with recommendations for control of cardiovascular parameters in the child and juvenile population with MD under treatment with antipsychotics. If we take into account the extent of recording physical and biochemical parameters, the clinical follow-up on metabolic side effects was low level in children with antipsychotics, since this should be performed in all cases in line with the recommendations in the clinical guidelines.10 Despite this underreporting of CVRF-M, the results were better than expected when compared to the frequency of recording for the group of patients with asthma, taking into account that this process was chosen because it requires prolonged follow-up to adulthood, as in the case of MDs.

In relation to other studies published on adolescent population, there are 2 types of studies, some oriented to assessing the recording of physical and biochemical parameters, and others only towards recording biochemical indicators. In the case of the first (physical and biochemical monitoring), the studies by Ghate et al.12 and Panagiotopoulos et al.13 should be noted. The first is a follow-up on a cohort of adolescents exposed to antipsychotics as compared with a population without exposure to antipsychotics, noting that the BMI recording (25.18%) was lower than in our study. This was 50%, while BP (54.90%) was similar (47.3% in our study). Regarding the recording of total cholesterol (2.44%) and glycaemia (1.74%), in the study by Ghate et al. this was approximately 10 times lower than in our study (28.2% and 11.4% respectively). Our findings were also in line with those of Panagiotopoulos et al.13 In this study we compared the evaluation of patients without prior antipsychotic treatment as compared with patients who were already in treatment for 2 years. Here, it was determined that during the years 2005 to 2007 only 32–37% of the paediatric patients receiving antipsychotic treatment were monitored for metabolism, revealing under-recording of CVRF-M.

With regard to the measurement of the ABG, the result obtained from low registration is contrasted with the scientific evidence that this is a parameter that should be measured in all patients at cardiovascular risk.14 In addition, Panagiotopoulos et al.,13 described recording ABG as a simple and sensitive tool to detect and assess the metabolic risk in children treated with antipsychotics.

In the studies where only biochemical parameters were analyzed, the results were also under-recorded, with a very low rate of detection, and with poorer results for assessment of physical parameters in the children themselves (physical percentages better than biochemical ones), and as compared with the percentages of recordings on the adult population.

Thus, in the cohort study on children and adolescents by Raebel et al.15 where the glycaemia level was assessed in patients who initiated antipsychotic treatment, only 11% of patients had baseline glycaemia recorded in the period before beginning and continuing this type of psychoactive drug. In addition, better results were obtained (15%) in the age groups from 12 to 18 years than in children under 12 years of age.

In the study by Haupt et al.,16 a retrospective cohort analysis of the adult and child-juvenile population was run for treatment with antipsychotics. The level of recording was also low, especially in the population of 12–18 years (between 5–15% for glucose and 0–5% for lipids vs 20% for glycaemia and 10% for lipids in adults).

In this analysis of other publications we also compared ourselves with a cross-sectional descriptive study conducted in our own environment (2008), although this was on the adult population, with a sample of 741 patients between 15 and 65 years, obtained from a population assigned to 7 different PHTs in Barcelona (n=1,102,530 inhabitants).17

When comparing the physical parameters of cardiovascular risk in our two studies run in the same region (adult and child population), we observed that the rate of BMI recordings was greater in children, those on BP were similar, and those on PBL were higher in adults (BMI: 50% in children vs 35.7% in adults, PA: 47.3% in children vs 46.5% in adults, PBL: 0.2% in children vs 16.3% in adults).

Regarding the analysis of biochemical parameter recordings, in our environment this is lower in children and adolescents (glycemia: 29.1% in children vs 47.1% in adults; total cholesterol: 28.2% in children vs 48.7% in adults; triglycerides: 11.4% in children vs 38.2% in adults).

Thus, our frequency of monitoring for physical and biochemical parameters came within the variability of results, and in our study a greater frequency of recording was detected in both types of parameters.

This low level of monitoring side effects may be due to the initial impression by clinicians that second generation antipsychotics are safer.18 This could also be explained by the lack of a monitoring protocol for paediatric patients under antipsychotic treatment oriented towards clinical efficacy and also to physical safety and health.19 For this reason, recently in Spain the “Clinical and therapy guide for early psychotic episodes in childhood and adolescence” has been produced,20 where there is insistence on anticipating and preventing the possible risks of the use of second generation antipsychotics. It makes recommendations for follow-up both on patients (monitoring clinical parameters, physical assessment, and biochemistry) and families (education about benefits and monitoring).

Despite this effort, in recent reviews such as that of De Hert et al.,21 and in studies where these clinical guidelines have been assessed,15 it is evident that despite making these recommendations, very poor results have been obtained, such as an increase from 11% to 15% after presenting the clinical guide.16

Regarding the difference between the results obtained for the adult and child population, this was probably due to the fact that, in general, fewer blood tests are run on children than on adults.22

In this study, we also provide data about the profile of use and type of antipsychotic in children and adolescents.

Regarding the use profile, in our sample the mean age of the children treated was 12 years and the diagnoses were diverse: ADHD, ASD and affective disorders, as in the case of others studies such as Ghate et al.12 where the group had a mean age of 15 years and the most frequent diagnosis (38%) was “other mental disorders”, which included ADHD, being the group that followed bipolar disorders (11% of the sample) in terms of frequency.

As regards the type of drug, second-generation antipsychotics were found to be more commonly used in our reference population, and more often prescribed than first-generation antipsychotics, with risperidone being the most frequently prescribed, as in the case of the results obtained in other studies.4,12,13,18,23,24

If the Cibersam guidebook is taken as a reference for Spain,20 it can be said that, at present, we need to be more preventive in monitoring metabolic side effects in the use of olanzapine and risperidone.

LimitationsIn this study we should consider the risk of a selection bias when selecting the population for comparison (patients with asthma). Thus, in the studies where two groups of patients were compared that differ in terms of the interest factor of the study (in our case, we compared the number of CVRF-M records in the MD group with the Asthma group), there may be a risk that they also differ in other aspects that may influence the characteristic of interest. To reduce this selection bias, asthmatic patients were chosen as a comparative group, since asthma is a process that behaves similarly to MD in terms of evolution, and which requires follow-up to adulthood, as does MD. In addition, asthma is a very frequent pathology in paediatrics, so this would enrich the sample of the comparative group. However, in this study the severity of each disease (MD vs Asthma) was not taken into account, a factor that could be relevant, given that MD could be considered more serious and therefore these patients may be monitored to a greater extent and have a larger number of records.

Another limitation is that, in this study, “recording” was considered as the simple fact of the parameter having been recorded only once during 2013, while the U.S.25,26 and Canadian guidelines10,27 indicate that parameters must be monitored several times a year (depending on the particular parameter). In this study, studying the number of times the parameters were recorded for each patient and analyzing a longer period of time would help us to be more precise, as has been done in previous studies.28

ConclusionsThis study provides real data on monitoring the side effects of antipsychotic treatments in children and adolescents from a sector of population in a Spanish region.

The study also provides evidence that adequate monitoring of cardiovascular risk is not being done in children and young people who take antipsychotics, given that all patients should have an assessment at least once a year.

It is important to assess the use of antipsychotics according to the differential profile of the potential metabolic side effects.28,29

Also, in this study we obtained data on the profile of use of antipsychotics in our community. The prescription of second generation drugs is more frequent than the prescription of first generation antipsychotics, with risperidone being the most used.

Ethical responsibilitiesProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments have been conducted on humans or animals for this research.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that patient information does not appear in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that patient data do not appear in this article.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: de la Torre Villalobos M, Martin-López LM, Fernández Sanmartín MI, Pujals Altes E, Gasque Llopis S, Batlle Vila S, et al. Monitorización del riesgo cardiovascular y metabólico en niños y adolescentes en tratamiento antipsicótico: un estudio descriptivo transversal. Rev Psiquiatr Salud Ment (Barc). 2018;11:19–26.