The international pandemic due to COVID-19 had an impact on every health area in an unprecedented way in the recent history of Medicine. Previous disasters, such as the sars-cov1 pandemic or the Ebola crisis, generated enough literature1 to recognize that there was a significant increase in the severity and incidence of mental disorders. This reality is observed again in 2020, when an increase in the number of cases of suicidal ideation,2 brief psychotic episodes3 and other mental disorders4,5 due to COVID-19 has been recorded.

Paradoxically, in certain mental health devices such as the Psychiatric Emergency Services, no such worsening has been observed; in fact, several countries have rather recorded a reduction in psychiatric emergencies after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic.6–8 However, most of these studies have just analyzed the rates of patients attending Emergency Services before and after the onset of the pandemic in absolute terms, without considering the periods of lockdown as an independent element under study. Therefore, the objective of this study is to describe the healthcare attention provided in a psychiatric emergency service during the months prior to, during, and after lockdown, comparing and establishing differences between them.

MethodologyThe registry of the Psychiatric Emergency Service of the University of Valencia Clinic Hospital has been analyzed, studying the volume of healthcare assistance performed and the psychiatric diagnosis (according to the CIE-10) of all patients. The data has been divided into three temporal groups. Given that the lockdown in Spain lasted exactly 50 days (from January 23 to March 13, 2020), those 50 days, the 50 days prior to this period, and the 50 days afterwards have been studied separately. In addition, severe mental disorders (including diagnoses within the psychotic, affective and personality spectrum) and mild to moderate disorders (including anxiety, adaptive disorders, drug addiction, child-adolescent and developmental disorders) have been grouped in order to compare how they vary in absolute and relative terms. After this, a statistical analysis was carried out using a Poisson regression, using the Chi-squared likelihood ratio test to evaluate the variation in the number of visits, and an ANOVA test on the proportion of severe and mild attention, both analysis comparing the three periods with statistical significance set at 0.05.

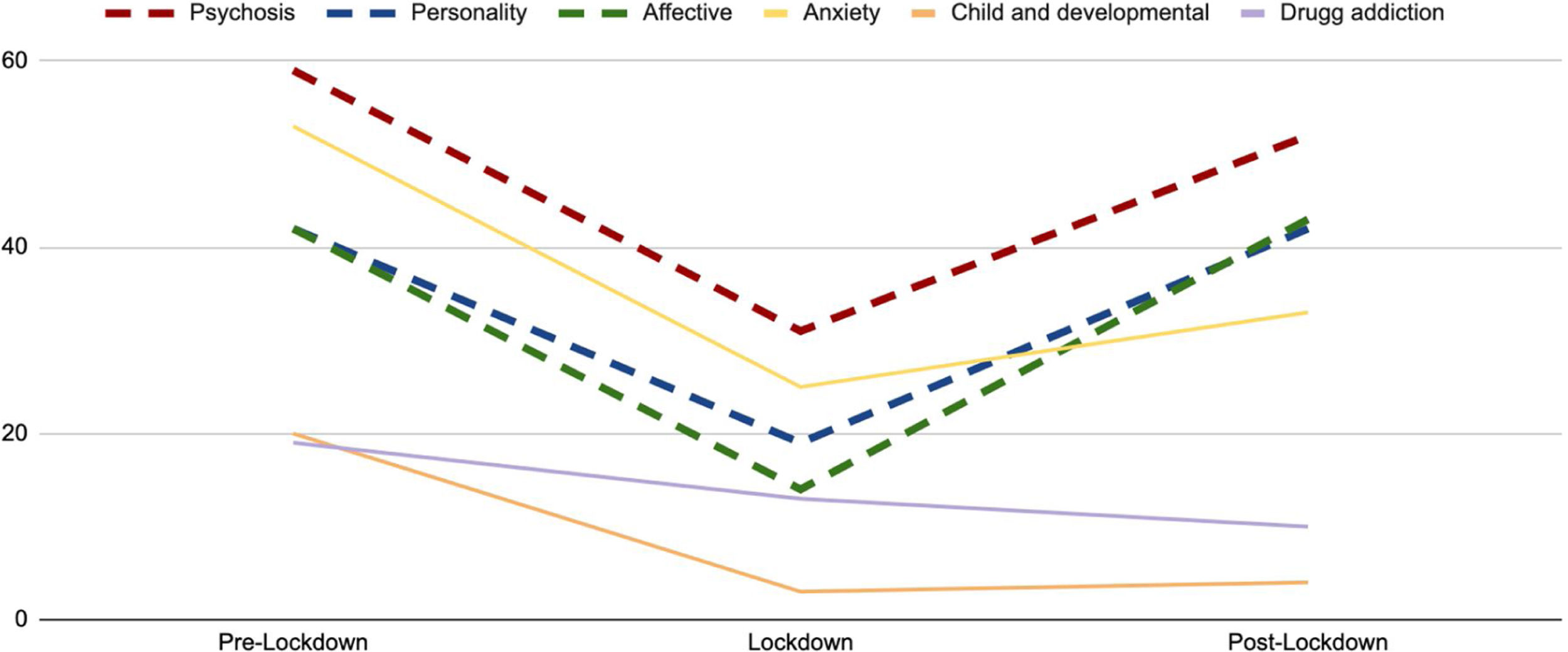

ResultsThe sample of the study corresponds to the total number of patients treated in 2020, and it is composed of 615 patients, 282 were attended in the pre-lockdown period, 120 during lockdown period and 213 in the post-lockdown period. During lockdown and post-lockdown, emergencies were reduced by 57.45% and 24.86%, respectively, compared to pre-lockdown rates and to the mean influx recorded during the last few years in those months. Comparing the influx obtained in the three periods of the last two years using Poisson regression, a p-value <0.001 has been obtained for the Chi-square likelihood ratio test (value of the D statistic=36.591), significant for p<.05. Regarding the analysis by diagnostic groups, the variation of the absolute frequencies between the different periods can be observed in Fig. 1.

Absolute frequencies of patients treated in the Psychiatric Emergency Service of the University of Valencia Clinic Hospital by groups of disorders according to the CIE-10 in the different time periods. In dashed lines it is possible to see severe mental disorders, in continuous lines mild or moderate ones.

It is interesting to note that the sum of patients with severe pathologies attended, remains constant in relative terms with respect to the total attention care carried out between the pre-lockdown and lockdown periods, with a minimum variation of 0.1%. However, in the post-lockdown period, this sum experiences a relative rise of 13.6% with respect to previous periods. The difference between severe and mild pathology attended during the different periods is statistically significant at p<.05, with an F statistic in the ANOVA test carried out on the proportion of severe cases per day of 4.85 and a p-value of .009.

ConclusionThis data matches the international trend of reduction in psychiatric emergencies after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. When comparing the lockdown and post-lockdown periods, we can more clearly identify that the lowest rates of visits occurred during the months in which more forceful social distancing and lockdown measures were applied. Emergency visits gradually increased in the later period, especially due to severe mental disorders.

The reduction observed during lockdown, together with the studies that describe an increase in the frequency and severity of mental disorders, should guide us to rethink how care is being offered. Reinforcing care outside the hospital environment,9 betting on devices such as home hospitalization units, extra-hospital mental health centres and assertive-community devices, are interesting options, especially now that due to the evolution of the pandemic, lockdowns like the one experienced in March and April 2020 are pressingly expected.

FundingNone declared.

Conflicts of interestThe authors do not declare any conflict of interest in the preparation of this article.