In recent years, due to the development of new technologies, virtual work teams have arisen as a new organizational form that offers businesses greater flexibility and adaptability in coping with new market challenges. The departments that manage high value-added projects are more susceptible to implementing virtual teams; the area of marketing and market research being one of them. However, the peculiarities of these teams present a real challenge for building trust within the team, with trust being one of the key factors for their success. Accordingly, this study considers various antecedent factors of trust toward leaders of virtual teams grouped in two blocks: the physical attributes (attractiveness) and the behavioral characteristics (justice and empathy) of the leader. Furthermore, the paper discusses how leadership style (transactional or transformational) can moderate the relationships between some of the previously mentioned variables. The results suggest a greater capacity for attractive, empathetic and just leaders to build trust. These results have interesting implications for management which are discussed along with the principle lines of future research.

En los últimos años, gracias al desarrollo de las nuevas tecnologías, han surgido los equipos de trabajo virtuales como una nueva forma organizativa que ofrece a las empresas una mayor flexibilidad y capacidad de adaptación de cara a hacer frente a los nuevos retos del mercado. Los departamentos que gestionan proyectos de alto valor añadido son los más susceptibles de implantar estos equipos, siendo el área de marketing e investigación de mercados uno de dichos departamentos. Sin embargo, las particularidades de estos equipos suponen un verdadero reto para el desarrollo de la confianza en el seno del equipo, que representa un factor fundamental para su éxito. En este sentido, la presente investigación considera diferentes factores antecedentes de la confianza hacia el líder de los equipos virtuales agrupados en 2 bloques: características físicas (atractivo) y comportamentales (justicia y empatía) del líder. Asimismo, se analiza cómo el estilo de liderazgo (transaccional o transformacional) puede moderar las relaciones entre algunas de las variables anteriormente mencionadas. Los resultados constatan la mayor capacidad de un líder atractivo, empático y justo para crear confianza. Estos resultados tienen interesantes implicaciones para la gestión, las cuales se analizan junto con las principales líneas de investigación futuras.

Changes in the competitive environment, as well as the enormous advances in the development of information technologies, have favored the emergence of new organizational forms that endow companies with greater flexibility. Especially noteworthy among the new organizational models are the so-called “virtual work teams”, characterized by the temporal and spatial distribution of its members and the use of technology as the fundamental medium for communication (Jarvenpaa & Leidner, 1999). These teams have contributed to the emergence of a new paradigm in human resource management where it is possible to work anytime and anywhere through technologically mediated communication (Cascio & Shurygailo, 2003). On the other hand, thanks to technology, it is possible to have access to the best talent for any given task regardless of their geographical location, thus, as previously mentioned, endowing organizations with greater flexibility and encouraging the creation of knowledge and the development of skills among employees.

The growth of virtual teams has been a constant since the end of the decade of the ‘90s. A study carried out by the consulting firm OnPoint Consulting (2013) affirms that more than 1.3 billion people work virtually and that 25% of the teams worldwide are virtual, data that gives an indication of the importance of virtual teams in organizations. This new form of organization is used especially in high value-added projects, where efficient knowledge management is required. Consequently, the area of marketing and market research is one of the functional areas of the organization in which the use of virtual teams can have a more positive impact. An example of this is the area of sales, where the use of CRM (Customer Relationship Management) tools allows the various members of a sales force to share different customer management strategies and optimize the sales effort without them having to share the same physical location, thereby improving their flexibility and responsiveness (Martins, Gilson, & Maynard, 2004). Another clear example is found in the area of product development where, through the use of virtual teams, it is possible to relocate the different phases of the process (design, production, etc.) while keeping all of the involved workers permanently connected, regardless of their geographical location.

However, these new teams bring with them a series of management challenges. Previous literature emphasizes that traditional leadership patterns cannot be used in the new virtual environment (Cascio, 2000; Santos, 2013), therefore it is necessary to adapt the management of the teams to the new virtual reality, where team leadership plays a fundamental role in the team's success. In this regard, the importance of trust in the team leader, recognized as a critical success factor in traditional settings, now takes on a new dimension. Patterns of leadership must be adapted to a new environment where communication becomes a significant barrier in the development of relationships among the members of a team. In fact, trust has been proposed as the primary challenge facing virtual teams today (Bullock & Tucker Klein, 2011).

While previous studies have analyzed trust from an organizational perspective, as well as the role that the leader plays in the creation of a trusting environment, there is currently no consistent theoretical and empirical body of knowledge regarding the study of trust in the leader in virtual settings and the variables that influence it (Zhang & Fjermestad, 2006). Thus, previous literature has not proposed a model that allows the factors that influence the building of trust in a virtual team leader to be accurately understood. This study seeks to reduce this shortcoming in the literature by analyzing some of those factors that may influence trust in a virtual leader.

This paper proposes two types of antecedent factors of trust in the leader of a virtual team: the physical attributes of the leader (degree of attractiveness) and the behavioral attributes of the leader (degree of empathy and justice). On the other hand, it should be noted that some of the relationships between the antecedent factors and trust may be moderated by other aspects, such as leadership style. With regards to this, theory points to two basic styles of leadership: leaders with a transformational style (Pillai, Schriesheim, & Williams, 1999), and leaders with a transactional style.

The paper is organized in the following manner. First, a review of the literature related to the variables used in the study is performed and the different research hypotheses are formulated. Later, the processes of data collection and the validation of the measurement scales used are explained. Subsequently, the hypotheses are tested and the results are discussed. Finally, the study's findings, key management implications, limitations and lines of future research are presented.

Literature review and the formulation of hypothesesTrust in the leaderTrust is a key ingredient in social and economic relationships and it is also one of the most determinant factors of performance within an organization. Previous literature has extensively addressed the study of organizational trust, yielding clear evidence that trust is vital within an organization. Today companies are multilevel structures where trust can be given at the individual, team or organizational level, therefore it is necessary to limit both the scope of the study of trust and the referents of the same (Fulmer & Gelfand, 2012), i.e., to whom trust is given. Accordingly, trust in the leader of a team would lie within the sphere of an analysis of individual trust and in reference to the team leader.

More specifically, research on trust in the leader of a team at an individual level yields a wide range of results. For example, trust in the leader is related to attitudes such as the satisfaction of subordinates with their leader, the perception that the leader exercises effective leadership, or a decrease in the degree of job uncertainty (Colquitt, LePine, Piccolo, Zapata, & Rich, 2012). Trust in a leader increases the support of subordinates for the leader, even when the results are unfavorable (Brockner, Siegel, Daly, Tyler, & Martin, 1997), as well as the commitment to the decisions made by the leader (Dirks & Ferrin, 2002). Thus, the importance of trust in a team leader is acknowledged as a way to maximize the possibility of the team's success (Burke, Sims, Lazzara and Salas, 2007).

Trust is a construct of a great relevance and therefore we can find a large number of definitions for it, especially at the individual level. However the vast majority of the definitions of trust focus on two key aspects of it (Dietz & Den Hartog, 2006). First, the willingness to trust, which refers to expectations, beliefs or attitudes toward the other person and the intention to rely on them. Second, the intention to accept a certain degree of vulnerability derived from the risk of trusting the other party (Mollering, 2006). In keeping with this, one of the most commonly used conceptualizations in the literature is that proposed by Mayer, Davis, and Schoorman (1995), according to which trust is the willingness of a party to be vulnerable to the actions of another party, with the expectation that the latter will perform a particular action that is important to the former. Focusing on the analysis of trust in the leader of a team, some empirical studies have conceptualized and measured trust as the expectation, or belief, that one can rely on the actions and words of another person and that this person has good intentions toward the former (Cummings & Bromiley, 1996; Dirks, 1999). Adapting this definition to the study of trust in a team leader, trust could be defined as the expectation or belief that one can rely on the words and actions of the leader and that the leader will have good intentions for the team at all times.

Previous research has shown that the recipients of trust, in this case the leader, show concern about a possible loss of trust of the people who rely on them (Ozer, Zhen, & Chen, 2011). That is why when leaders can create positive perceptions in the people that trust them, then it is more likely that a trusting relationship can be developed. In other words, the level of trust in leaders is related to the perception on behalf of their subordinates of a series of patterns of behavior (Dirks & Ferrin, 2002). These patterns of behavior are precisely those that correspond to the different dimensions of trust. Benevolence is the perception that there is a positive predisposition toward an individual who is worthy of trust, that is, a relationship in which there is goodwill between the parties (Dirks & Ferrin, 2002; Mayer et al., 1995). Ability refers to a person's capacity to perform a specific task (Mayer et al., 1995). Finally, integrity is the perception that the person being trusted adheres to ethical principles that are considered to be fundamental for the establishment of a relationship (Butler, 1991).

The effect of the physical attractiveness of the leaders on the trust placed in themPrevious research in the area of social psychology and marketing has proven that the perception of the person who delivers a message has a clear influence on the effectiveness of the message (Reingen and Kernan, 1994). On the other hand, the effect of attractiveness has drawn the attention of social psychology for many years. In the early works of Kelman (1961) it was argued that the attractiveness of the person who delivers a message is a relevant dimension that influences whether or not the message is approved by the receiver. With the objective of acknowledging physical attractiveness as an objectively measurable trait, previous research has focused on the deductions made by people with regards to their perception of other people's appearance. Articulated through stereotypes such as “What is beautiful is good” (Dion, Berscheid, & Hatfield, 1972; Lorenzo, Biesanz, & Human, 2010), “You can judge the book by its cover” (Yamagishi, Tanida, Mashima, Shimona, & Kanazawa, 2003) or “Beauty Pays: Why Attractive People are more Successful” (Hamermesh, 2011), the common framework indicates that physical attractiveness has a kind of ‘halo effect’ that conditions the perception of others (Vogel, Kutzner, Fiedler, & Freytag, 2010). In this sense, the more physically attractive people are usually more successful than the unattractive ones, given that there is a belief that attractive people have a series of more positive characteristics attributed to them compared to less attractive people (Riggio, 1999).

Although the perception of the degree of attractiveness of an individual has been used in different areas of the social sciences, such as marketing and psychology (Mishra, Clark, & Daly, 2007), with the objective of analyzing how these perceptions affect individual behavior, it is still a little studied aspect in the management of work teams and in the relationship of trust between leaders and their subordinates. Furthermore, the effect of physical attractiveness has been the subject of study in decision-making for situations such as the decision to hire or electoral behavior (Langlois and Kalakanis, 2002). Research in the area of psychology supports the fact that attractive people are more likely to possess a wide variety of positive qualities, such as intelligence and sympathy (Hatfield and Sprecher, 1986). Accordingly, human beings frequently attribute positive characteristics to attractiveness and negative characteristics to the lack of attractiveness (Eagly, Ashmore, Makhijani, & Longo, 1991). This stereotype associated with attractiveness leads to systematic biases of perception and erroneous judgments and attribution errors. Easily observable features, such as attractiveness, can be used to categorize individuals on the basis of stereotypes (Jones, Moore, Stanaland, & Wyatt, 1998), and the perceptions of these attributes are often instant, automatic and instinctive (Willis & Todorov, 2006).

Based on the foregoing arguments, it is reasonable to believe that leaders considered attractive by their employees will generate trust more easily. Accrodingly, the first working hypothesis is proposed:H1 A greater degree of perceived attractiveness of the leaders will positively influence the level of trust in them.

In recent years all aspects related to emotional intelligence have prompted an extensive debate in the literature, especially with regards to its definition and primary components (e.g. Barrett, 2006). The concept of emotional intelligence, introduced by Salovey and Mayer (1990), has emerged in combination with an emphasis on the interpersonal aspects of the emotions (Frijda & Mesquita, 1994). From a social-functional point of view, emotions are signs of relevant information that can be used to understand how to successfully participate in interactions with others (Keltner and Kring, 1998). Empathy, i.e. the ability to understand the feelings of others and internalize them as if they were one's own, represents the core concept of emotionally intelligent behavior (Salovey & Mayer, 1990). Plutchik (1987) describes empathy as an exchange of positive and negative emotions that fosters bonding among people.

The concept of empathy has also been analyzed in business management. Goleman, Boyatzis, and Mckee (2002) argue that empathy is the fundamental competence of social consciousness and the condition sine qua non of all effectiveness in the workplace life within the company. In the context of the interaction leader – subordinate, the empathy of leaders with their subordinates can affect the degree to which the leaders take them into consideration (Zaki, Bolger, & Ochsner, 2008). Empathy is recognized as a key element for successful leadership (Bass, 1999; Judge, Piccolo, & Ilies, 2004), in fact, there are studies that suggest that empathetic leaders adapt their behavior after evaluating their subordinates (Batson, 1991).

Research on emotions in work environments suggest that social manifestations in labor interactions have a very significant impact on employee behavior (Hochschild, 1983). It has also been proposed that emotions have an important influence on the reactions of subordinates toward their leader, which may affect their behavior (Newcombe and Ashkanasy, 2002). On the other hand, the work of Brundin, Patzelt, and Shepherd (2008) suggests that leaders who show positive emotions toward their subordinates benefit from a better predisposition of the teams they lead to act as cohesive groups. Furthermore, the literature on team management and leadership acknowledges that there is a relationship between personal communication and trust (Zolin, Fruchter, & Hinds, 2003). In fact, Feng, Lazar, and Preece (2004), argue that the group's management should develop mechanisms so that the constituents identify with other members of the group with the end of fostering an empathic attitude that helps build trust.

Given that previous research has suggested that empathetic behavior may be associated with higher levels of trust, it is reasonable to think that leaders that are more empathetic toward their subordinates may be capable of building greater trust. Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:H2 A greater degree of perceived empathy in the leaders will positively affect the level of trust in them.

As previously mentioned, physically attractive people tend to elicit a better response from others than those that are less attractive (Shinners & Morgan, 2009). This stereotype is determined by the so-called “halo effect”. The halo effect refers to a cognitive bias whereby the perception of a particular trait of a person (in this case the attractiveness of the leader) influences the perception of the other attributes of the individual. By virtue of the stereotypes associated with attractiveness, people often confer positive attributes to attractive people and negative attributes to less attractive people (Eagly et al., 1991). In this regard, Mathes and Kahn (1975) argue that the physically more attractive people have greater empathic power than less attractive people precisely due to the halo effect that surrounds them.

From these arguments one may derive the idea that the degree of empathy perceived in leaders could be partially determined by their degree of attractiveness, such that attractive leaders would be able to improve the perception of empathy among their employees, since these make the subconscious association that attractive people tend to be more empathetic. Thus, the following hypothesis is proposed.H3 A greater degree of perceived attractiveness of the leaders will impact positively on the level of perceived empathy in them.

Over the past 30 years organizational justice has been researched by the field of social psychology (Trevino and Weaver, 2001). Much of the interest in the study of justice is due to the important implications that the perception of organizational justice by the employees has for the workplace (Cohen-Charash & Spector, 2001), such as satisfaction with the job and with the leader (Alexander & Ruderman, 1987), organizational commitment (Masterson, Lewis, Goldman, & Taylor, 2000) and on-the-job performance (Ball, Trevino, & Sims, 1994), among others.

Organizational justice refers to the subjective sense of fairness that people perceive (Di Fabio & Palazzeschi, 2012). Justice has been divided into three areas, each of which has been examined in relation to trust in the leader. The areas of organizational justice include, on one hand, procedural justice which refers to policies and procedures being executed consistently (e.g. Viswesvaran & Ones, 2002). Secondly, distributive justice, which refers to rewards and promotions being granted consistently (e.g. Aryee, Budhwar, & Chen, 2002). Finally, interactional justice which postulates that people are treated with respect (e.g. Aryee et al., 2002).

Trust and organizational justice are areas of interest within business management research. Trust triggers cooperative behavior among workers and reduces conflicts and transaction costs (Rousseau, Sitkin, Burt, & Camerer, 1998). Organizational justice is also positively related to commitment to, and trust in, the organization and among its employees (Sweeney & Mcfarlin, 1993). Generally speaking, the literature suggests that people want to be treated fairly and consistently, and this brings them to trust (Ambrose & Schminke, 2003). Therefore, it is reasonable to believe that those leaders who are perceived to be fairer will be able to build greater trust among their subordinates. Accordingly, it is possible to propose the following hypothesis.H4 A greater degree of perceived justice in the leaders will impact positively on the level of trust in them.

The literature on team management has focused its attention on different leadership styles (e.g. Bass, Avolio, Jung, & Berson, 2003), however, the most prominent paradigms are transformational leadership and transactional leadership (Smith, Larsen Andras, & Rosenbloom, 2012). Transactional leadership theory argues that leaders focus exclusively on achieving their short-term goals and use a system of rewards to induce the desired behavior in their subordinates and achieve those goals. On the other hand, transformational leadership theory holds that leaders can motivate employees by taking into account aspects that go beyond the mere self-interest of the employee for the job. Bass (1985) suggests that transformational leadership is a more appropriate approach to leading the human resources of a team. Transformational leaders are flexible, they understand the need to collaborate with their employees, and readily adapt to changes in the environment.

A review of the leadership literature reveals that trust has been the most often cited topic in the study of transformational leadership (Dirks & Ferrin, 2002; Wang, Oh, Courtright, & Colbert, 2011). The research of Dirks and Ferrin (2002) describes a large number of studies that have examined the relationship between transformational leadership and trust (e.g. Bass, 1985; Bass and Avolio, 1994; Dirks & Ferrin, 2002; Jung and Avolio, 2000; Podsakoff, MacKenzie, and Bommer, 1996). In addition to other results, the transformational style of leadership has been identified as an antecedent of trust, as well as a moderating variable of the same (e.g. Avolio et al., 2004).

With regards to physical attractiveness, the literature acknowledges that people tend to attribute desirable personality characteristics to physically attractive individuals (Dion, 1986). Thus, in an analysis by Eagly et al. (1991) it was shown that attractive people were strongly correlated with attributes such as social competence and intellectual capacity, and along the same lines, attractive people were also seen to be more competent and more intelligent (Ross & Ferris, 1981). More recent research suggests that more attractive people tend to obtain better results in situations such as job interviews (e.g. Eagly & Wood, 2012) or even in the election of political leaders (Berggren, Jordahl, & Poutvaara, 2010). Therefore it is a fact that people tend to associate positive attributes with individuals that are more physically attractive. Empathy is also considered a positive trait in a person, especially when they have to lead people or work groups (Wolff, Pescosolido, & Druskat, 2002).

Furthermore, the literature has also shown great interest in empirically demonstrating when and how the effect of attractiveness is strengthened or weakened (Ahearne, Gruen, & Jarvis, 1999). In keeping with this, research in the area of sales management suggests that the effect of attractiveness decreases as the relationship between the two parties develops (Reingen & Kernan, 1993). Similarly, recent research in the area of leadership demonstrates that the perceived attractiveness of leaders can be altered inasmuch as there is an increased exposure to them (Reis, Maniaci, Caprariello, Eastwick, & Finkel, 2011) or as people become more familiar with the leader.

With regards to leadership styles, a similar effect can be expected. Accordingly, while in the early stages of relationships the effect of attractiveness may be relevant, as the leader-subordinate relationship matures, the influence of attractiveness should decline. Therefore, as the management style of the leader consolidates, the weight of attractiveness relative to other variables decreases. In other words, when leadership styles are well defined, the judgments that subordinates make concerning their leaders are influenced less by physical attractiveness, and more by other attributes directly related to their management style, for example if the leaders are able to solve problems or the by way they treat their workers.

The following working hypothesis is proposed on the basis of these arguments:H5 When leadership styles are well-defined, the attractiveness of the leaders will have less influence on the trust in them.

Several papers have studied the role of emotional intelligence, demonstrating that a relationship exists between emotional intelligence (and therefore empathy as a key element) and effective leadership, especially when the leader employs a transformational style of leadership (e.g. Sunindijo, Hadikusumo, & Ogunlana, 2007). That is, empathy is a trait that is usually associated with transformational leadership styles. Conversely, empathy is a quality that is much less associated with transactional leadership styles, which are based on highly formalized reward systems.

Furthermore, in the area of psychology, expectations are associated with the reasonable possibility that a given event may occur. In the event that expectations are not met, it is possible that a misalignment of expectations may lead to disappointment, however if in the end the reality surpasses the expectations, it produces a positive effect. The Expectancy Theory developed by Vroom (1964) holds that individuals have beliefs and hopes about the future events in their lives and, consequently their behavior is the result of conscious choices among alternatives and choices based on beliefs and attitudes with the purpose of these choices being to maximize the rewards and minimize the disappointments.

Based on the above arguments, the fact that the subordinates have a perception of empathy in their leader and besides that leader employs a transactional leadership style could actually strengthen the relationship between trust and empathy. This could be explained by the fact that empathy is an unexpected trait in a transactional leader and therefore could create a surprise effect that reinforces the above-mentioned relationship. On the other hand, the subordinates of very transformational leaders should have high expectations regarding their degree of empathy. This is due to the fact that empathy is a trait that is clearly associated with this style of leadership. Therefore, the power of empathy as a builder of trust should decline as the perception of a transformational leadership style increases. In other words, for a transformational leader the perception of empathy does not represent a particularly relevant sign since it is implicit in that style of leadership. Based on these arguments, the following working hypothesis is proposed.H6 The influence of the perceived empathy in the leaders on the trust in them will be: (a) greater when the leader employs a more transactional leadership style or (b) less when the leader employs a more transformational leadership style.

The data necessary for this study was obtained through a self-administered survey on the Internet taken by people who regularly work in virtual teams. A total of 248 questionnaires were received which, after analyzing for missing data and outliers, yielded 241 valid questionnaires. Structural equation modeling was used for the data analysis.

The process to validate the scales proposed for the measurement of the component variables of the model is made up of the following phases:

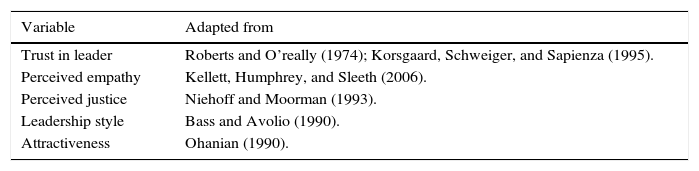

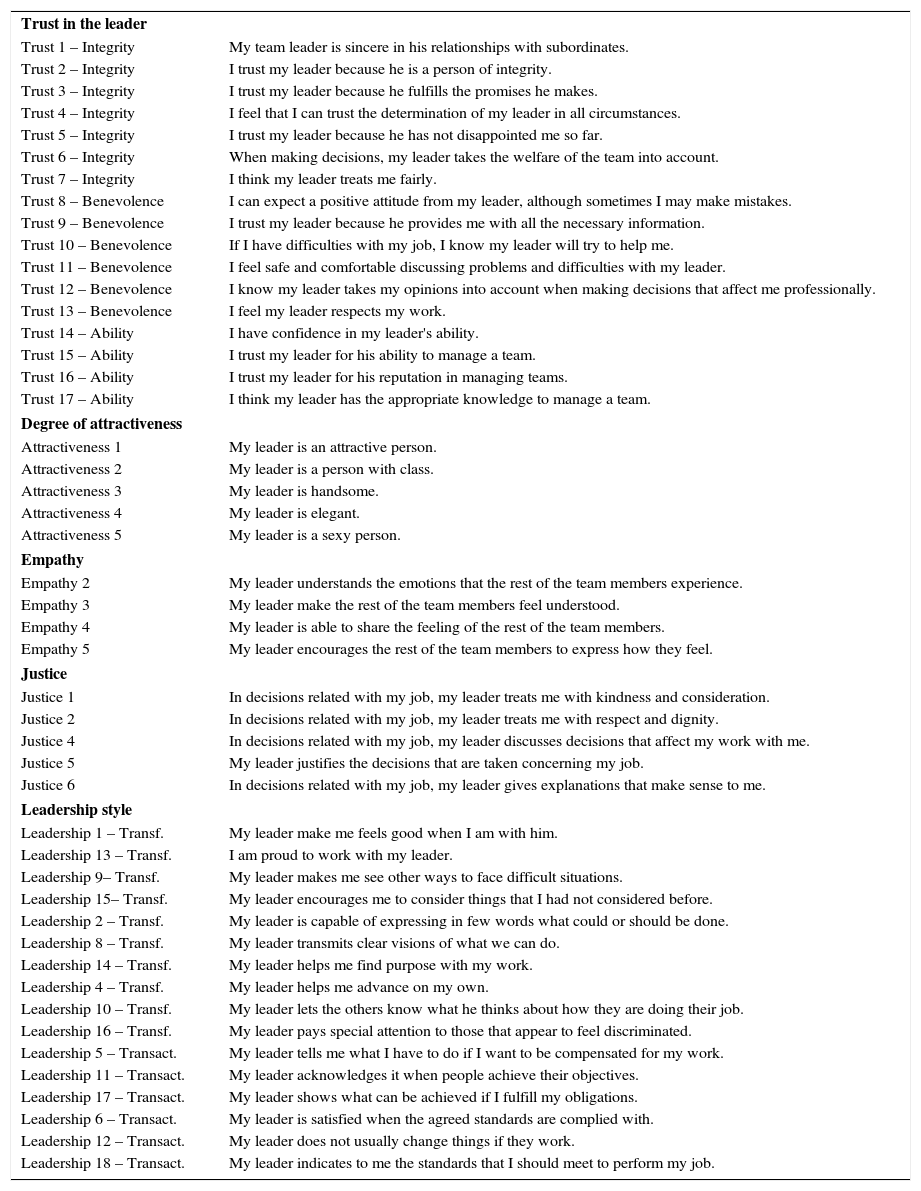

Content and face validityThe development of the measurement scales was based on a review of previous literature (see Table 1); due to this review it was possible make a proposal for the preliminary scales. Nevertheless, the scales had to be adapted to the context of virtual work teams.

Content and face validity.

| Variable | Adapted from |

|---|---|

| Trust in leader | Roberts and O’really (1974); Korsgaard, Schweiger, and Sapienza (1995). |

| Perceived empathy | Kellett, Humphrey, and Sleeth (2006). |

| Perceived justice | Niehoff and Moorman (1993). |

| Leadership style | Bass and Avolio (1990). |

| Attractiveness | Ohanian (1990). |

The objective of this adaptation was to ensure face validity, which is defined as the extent to which the measurement scale reflects that which is intended to be measured. Face validity is often confused with the concept of content validity. However, content validity is the extent to which the items correctly represent the theoretical content of the construct and that it is guaranteed by a thorough review of the literature. The degree of face validity was contrasted using a variation of the Zaichkowsky model (1985) in which each item is classified by a group of experts as being “clearly representative”, “somewhat representative” or “not representative”. Finally, in line with Lichtenstein, Netemeyer, and Burton (1990), each individual items was retained if there was a high degree of consensus among the experts.

Exploratory analysis of reliability and dimensionalityThe validation process included an exploratory analysis of the reliability and dimensionality of the instruments of measurement. Firstly, the Cronbach's alpha method was used to assess the reliability of the scales, where a minimum of 0.7 was considered acceptable (Nunnally, 1978). The variables being considered easily surpassed this minimum threshold. Furthermore, the item-total correlation, which measures the correlation of each item with the sum of the rest of the items of the scale, was found to surpass to the minimum of 0.3 (Nurosis, 1993).

Secondly, the degree of unidimensionality of the scales was evaluated by means of a factor analysis. The extraction of factors was based on the existence of eigenvalues greater than 1, while also requiring factor loadings greater than 0.5 for each item, and that the explained variance for each factor extracted be significant. By this means, a single factor corresponding to each one of the proposed scales, with a significant variance, and items with loads greater than the minimum required, were extracted.

Confirmatory analysis of dimensionalityConfirmatory Factor Analysis was used to confirm the dimensional structure of the scales. EQS 6.1 statistical software was used to perform the analyses and the Robust Maximum Likelihood Estimation method was employed because it provides greater security when working with samples that could present some type of multivariate abnormality. A factorial model including all of the considered variables was designed following the criteria proposed by Jöreskog and Sörbom (1993):

- 1.

The weak convergence criterion, by which the indicators that do not show significant factorial regression coefficients (t-student>2.58; p=0.01) are eliminated.

- 2.

The strong convergence criterion, by which all of the indicators whose standardized coefficients are less than 0.5 are eliminated.

- 3.

The elimination of those indicators that contribute the least to the explanation of the model. More specifically, for the study in question, those indicators whose R2 was less than 0.3 were excluded.

In this stage 8 items were eliminated. The adjusted confirmatory model presented acceptable values (Bentler–Bonett Non-Normed Fit Index=0.895; Comparative Fit Index (CFI)=0.908; Bollen (IFI) Fit Index=0.909; Root Mean Sq. Error of App. (RMSEA)=0.064; 90% Confidence Interval of RMSEA (0.056, 0.072)).

Finally, to confirm the existence of multidimensionality in the variable “trust in the leader”, a Rival Models Strategy was developed (Anderson & Gerbing, 1988) whereby a second-order model in which various dimensions measure the multidimensional construct under consideration is compared with another first-order model in which all the items are loaded on single factor (Steenkamp & Van Trijp, 1991). The results corroborated the multidimensional structure of the variable trust (integrity, benevolence, and ability) since the second-order model had a much better fit than the alternative first-order model.

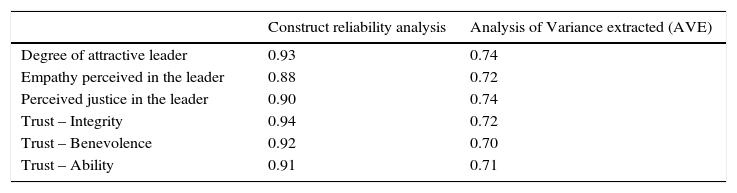

Construct reliabilityAlthough Cronbach's Alpha is the generally accepted indicator to assess the reliability of the scales, some authors argue that this indicator may understate reliability (e.g. Smith, 1974). Therefore, the use of an additional statistic such as a composite and construct reliability analysis (FCC) is recommended by different authors such as Jöreskog (1971). The results are positive taking 0.7 as a minimum value (Steenkamp & Geyskens, 2006), as shown in Table 2.

Construct reliability and construct validity.

| Construct reliability analysis | Analysis of Variance extracted (AVE) | |

|---|---|---|

| Degree of attractive leader | 0.93 | 0.74 |

| Empathy perceived in the leader | 0.88 | 0.72 |

| Perceived justice in the leader | 0.90 | 0.74 |

| Trust – Integrity | 0.94 | 0.72 |

| Trust – Benevolence | 0.92 | 0.70 |

| Trust – Ability | 0.91 | 0.71 |

Construct validity was analyzed using two fundamental criteria for validity:

Convergent validity: Indicates whether the items that compose scales converge toward a single construct. Convergent validity was confirmed when it was shown that the factor loading of each indicator was greater than 0.5 and significant at the level of .01 (Steenkamp & Geyskens, 2006). Furthermore, the Analysis of Variance Extracted (Ping, 2004) was also used following the criterion of Fornell & Larcker (1981) which states that the measurements with an adequate level of convergent validity should contain less than 50% of the variance of the error (which implies an AVE statistic value greater than 0.5). The results obtained were satisfactory as shown in Table 2.

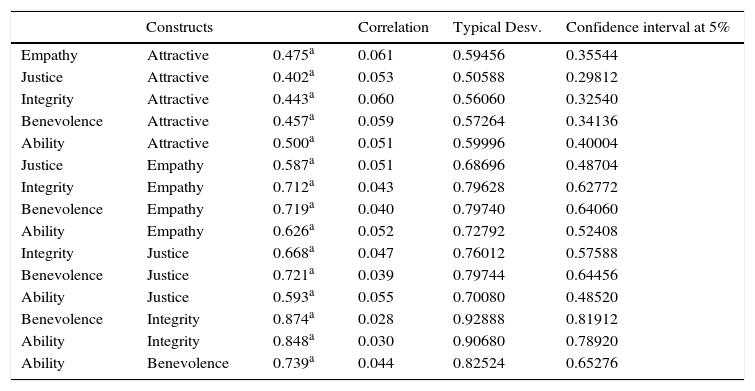

Discriminant validity: Tests whether the construct being analyzed is significantly distant from other constructs that are not theoretically related to it. Discriminant validity was assessed using two criteria: (1) verifying that the value of 1 was not found in the confidence interval for correlations between the different scales, and (2) checking that the correlation between each pair of scales was not significantly greater than 0.8. The results are satisfactory with the exception of the correlations between some of the dimensions of trust, which surpass 0.8. Nevertheless, this circumstance is understandable given that they form part of the same second-order construct. In addition, the results of the confidence intervals were satisfactory in all cases. Therefore, the level of discrimination was considered to be sufficient and the next stage of analysis was initiated (Table 3).

Table 3.Discriminant validity.

Constructs Correlation Typical Desv. Confidence interval at 5% Empathy Attractive 0.475a 0.061 0.59456 0.35544 Justice Attractive 0.402a 0.053 0.50588 0.29812 Integrity Attractive 0.443a 0.060 0.56060 0.32540 Benevolence Attractive 0.457a 0.059 0.57264 0.34136 Ability Attractive 0.500a 0.051 0.59996 0.40004 Justice Empathy 0.587a 0.051 0.68696 0.48704 Integrity Empathy 0.712a 0.043 0.79628 0.62772 Benevolence Empathy 0.719a 0.040 0.79740 0.64060 Ability Empathy 0.626a 0.052 0.72792 0.52408 Integrity Justice 0.668a 0.047 0.76012 0.57588 Benevolence Justice 0.721a 0.039 0.79744 0.64456 Ability Justice 0.593a 0.055 0.70080 0.48520 Benevolence Integrity 0.874a 0.028 0.92888 0.81912 Ability Integrity 0.848a 0.030 0.90680 0.78920 Ability Benevolence 0.739a 0.044 0.82524 0.65276

The measurement scales used can be seen in Table 4.

Scales.

| Trust in the leader | |

| Trust 1 – Integrity | My team leader is sincere in his relationships with subordinates. |

| Trust 2 – Integrity | I trust my leader because he is a person of integrity. |

| Trust 3 – Integrity | I trust my leader because he fulfills the promises he makes. |

| Trust 4 – Integrity | I feel that I can trust the determination of my leader in all circumstances. |

| Trust 5 – Integrity | I trust my leader because he has not disappointed me so far. |

| Trust 6 – Integrity | When making decisions, my leader takes the welfare of the team into account. |

| Trust 7 – Integrity | I think my leader treats me fairly. |

| Trust 8 – Benevolence | I can expect a positive attitude from my leader, although sometimes I may make mistakes. |

| Trust 9 – Benevolence | I trust my leader because he provides me with all the necessary information. |

| Trust 10 – Benevolence | If I have difficulties with my job, I know my leader will try to help me. |

| Trust 11 – Benevolence | I feel safe and comfortable discussing problems and difficulties with my leader. |

| Trust 12 – Benevolence | I know my leader takes my opinions into account when making decisions that affect me professionally. |

| Trust 13 – Benevolence | I feel my leader respects my work. |

| Trust 14 – Ability | I have confidence in my leader's ability. |

| Trust 15 – Ability | I trust my leader for his ability to manage a team. |

| Trust 16 – Ability | I trust my leader for his reputation in managing teams. |

| Trust 17 – Ability | I think my leader has the appropriate knowledge to manage a team. |

| Degree of attractiveness | |

| Attractiveness 1 | My leader is an attractive person. |

| Attractiveness 2 | My leader is a person with class. |

| Attractiveness 3 | My leader is handsome. |

| Attractiveness 4 | My leader is elegant. |

| Attractiveness 5 | My leader is a sexy person. |

| Empathy | |

| Empathy 2 | My leader understands the emotions that the rest of the team members experience. |

| Empathy 3 | My leader make the rest of the team members feel understood. |

| Empathy 4 | My leader is able to share the feeling of the rest of the team members. |

| Empathy 5 | My leader encourages the rest of the team members to express how they feel. |

| Justice | |

| Justice 1 | In decisions related with my job, my leader treats me with kindness and consideration. |

| Justice 2 | In decisions related with my job, my leader treats me with respect and dignity. |

| Justice 4 | In decisions related with my job, my leader discusses decisions that affect my work with me. |

| Justice 5 | My leader justifies the decisions that are taken concerning my job. |

| Justice 6 | In decisions related with my job, my leader gives explanations that make sense to me. |

| Leadership style | |

| Leadership 1 – Transf. | My leader make me feels good when I am with him. |

| Leadership 13 – Transf. | I am proud to work with my leader. |

| Leadership 9– Transf. | My leader makes me see other ways to face difficult situations. |

| Leadership 15– Transf. | My leader encourages me to consider things that I had not considered before. |

| Leadership 2 – Transf. | My leader is capable of expressing in few words what could or should be done. |

| Leadership 8 – Transf. | My leader transmits clear visions of what we can do. |

| Leadership 14 – Transf. | My leader helps me find purpose with my work. |

| Leadership 4 – Transf. | My leader helps me advance on my own. |

| Leadership 10 – Transf. | My leader lets the others know what he thinks about how they are doing their job. |

| Leadership 16 – Transf. | My leader pays special attention to those that appear to feel discriminated. |

| Leadership 5 – Transact. | My leader tells me what I have to do if I want to be compensated for my work. |

| Leadership 11 – Transact. | My leader acknowledges it when people achieve their objectives. |

| Leadership 17 – Transact. | My leader shows what can be achieved if I fulfill my obligations. |

| Leadership 6 – Transact. | My leader is satisfied when the agreed standards are complied with. |

| Leadership 12 – Transact. | My leader does not usually change things if they work. |

| Leadership 18 – Transact. | My leader indicates to me the standards that I should meet to perform my job. |

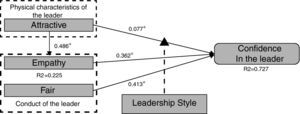

To contrast the proposed hypotheses, the structural equations model shown in Fig. 1 was developed.

The fit of the model presented acceptable values (Bentler–Bonett Non-normed Fit Index=0.897; Comparative Fit Index (CFI)=0.920; Bollen (IFI) Fit Index=0.921; Root Mean Sq. Error of App. (RMSEA)=0.092; 90% RMSEA Confidence Interval (0.082, 0.110)).

Focusing on the antecedents of trust in a virtual leader, we observe that physical attractiveness has a positive and significant effect on trust in a leader (β=0.077; p<0.05). Therefore the hypothesis H1 is accepted. Likewise, behavioral traits of a virtual leader such as empathy (β=0.362; p<0.01) and perceived justice (β=0.413; p<0.01) exert a positive and significant effect on trust, therefore hypotheses H2 and H4 are also accepted. Furthermore, the results reveal the existence of a positive and significant relationship between the degree of perceived attractiveness and the perceived empathy of a leader (β=0.486; p<0.01), allowing us to also accept hypothesis H3.

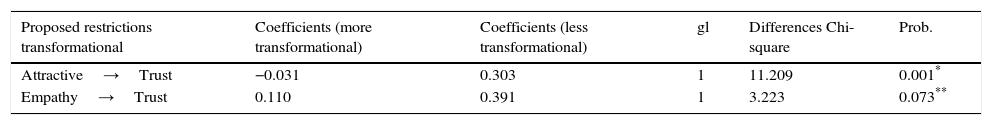

In order to test the moderating effect of leadership style, a multi-sample analysis was performed. For each of the analyses, the total sample of individuals was divided into two groups. To form the groups, the mean of the corresponding item was taken in each case, and a series of cases around this value (±½standard deviation) were eliminated. Secondly, an LM-Test analysis, “Lagrange Multiplier Test” (Engle, 1984) was performed in order to check if differences existed among the parameters obtained for the two groups and if these differences were significant.

Hypothesis H5 argues that for well-defined leadership styles, i.e. highly transformational or highly transactional styles of leadership, the leader's attractiveness will have less influence on trust. The analysis of the results reveals that the relationship between the degree of attractiveness and trust in the leader is moderated in the case where the leader employs a more transformational leadership style (p<0.01). In fact, the presence of a negative parameter (β=−0.031; p<0.01) for the attractiveness→trust relationship for the more transformational sample suggests that the effect is not only weaker, but indicates that the influence of attractiveness on trust diminishes for very transformational leadership styles (see Table 5). However, there is no statistically significant moderating effect when the leader exerts a very transactional leadership style (β=−0.003, p=0.217). Therefore, hypothesis H5 should be rejected.

Multi-sample analysis.

| Proposed restrictions transformational | Coefficients (more transformational) | Coefficients (less transformational) | gl | Differences Chi-square | Prob. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attractive→Trust | −0.031 | 0.303 | 1 | 11.209 | 0.001* |

| Empathy→Trust | 0.110 | 0.391 | 1 | 3.223 | 0.073** |

| Proposed restrictions transactional | Coefficients (more transactional) | Coefficients (less transactional) | gl | Differences Chi-square | Prob. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attractive→Trust | −0.003 | 0.131 | 1 | 1.524 | 0.217 |

| Empathy→Trust | 0.313 | 0.475 | 1 | 0.916 | 0.339 |

On the other hand, hypothesis H6 postulates that the influence of the perceived empathy of the leader on trust will be: (a) greater when the leader exercises more a transactional a leadership style or (b) less when the leader employs a more transformational style. In light of the results, one can observe that there is no significant moderating effect in the case of transactional leadership. On the other hand, there is a weak moderating effect (p=0.073) for transformational leadership, given that the influence of empathy on trust appears to be less for more transformational leaderships. Therefore, hypothesis H6 must also be rejected.

ConclusionsTrust in the leader plays an important role in the success of a team (Kayworth & Leidner, 2000). That is why building relationships based on trust among the members of the team should be a primary concern of the leaders. Although the literature has acknowledged the importance of trust for the job to be done by virtual team leaders (e.g. Greenberg, Greenberg, & Antonucci, 2007), it is still necessary to delve further into the attributes that a trustworthy leader should possess in this new context. The literature has proposed certain characteristics of individuals that can affect the attitudes toward them and consequently the building of trust. This paper analyzes how certain physical and behavioral aspects of leaders can affect the building of trust in their subordinates, as well as the role of leadership style as a factor that could moderate some of the proposed relationships.

First, the results confirm the influence that both the physical characteristics and the behavior of the leader have on trust in a virtual leader. More specifically, the degree of attractiveness perceived in virtual team leaders exerts an influence on the trust generated in them. On the other hand, the characteristics of the behavior of leaders toward their subordinates also exerts a positive effect on trust. More specifically, the empathy that subordinates perceive in their leader makes them more willing to give the leader their trust. Similarly, the perceived justice of the leader has a positive effect on trust. Furthermore, the attractiveness of the leader has a positive effect on empathy, which demonstrates that, in a virtual setting, the stereotypes regarding attractiveness proposed in the literature continue to be valid.

The literature acknowledges leadership style as one of the variables that can moderate the relationships that develop within a workgroup (Vries, Roe, & Taillieu, 2002), for this reason this study aims to analyze whether this is also true in virtual environments. In this regard, whether or not the effect of attractiveness can diminish as the relationship between the leader and the subordinate matures when the leader employs a determined leadership style (more transactional or more transformational) was also analyzed. On this point, it would be interesting to evaluate whether the variable that moderates the relationship is the leadership style or, on the contrary, it is maturing of the leader-subordinate relationship that causes the effect of the attractiveness to diminish. There are several studies that point in this direction (Reis et al., 2011), however the results are inconclusive and therefore further research would be necessary to delimit the effect of the moderation that the two variables raise. Furthermore, it would be interesting to further analyze whether the different leadership styles proposed in this paper could have an influence on the fact that the moderation proposed between the attractiveness of the leader and trust only occurs for transformational leadership styles.

Furthermore, the possible moderating effect of leadership style on the relationship of empathy with trust was also analyzed. According to the results, the leadership style perceived by subordinates appears to only influence transformational leadership styles, given that the influence of empathy on trust seems lower for the more transformational leaderships.

The results concerning the moderation of leadership styles are interesting given that research conducted in non-virtual contexts suggests the existence of moderating effects as a consequence of leadership style (Connelly & Ruark, 2010). A possible explanation for this result could be that the characteristics of the online environment reduced, modified or eliminated the effect of the leadership style (Cote, Lopes, Salovey, & Miners, 2010). Another possible explanation could be that the variable affected, in this case empathy, is not affected in any way by the style of leadership, and that this variable is completely independent of the other. In any case, further research in this area is necessary to more deeply understand the behavior of certain variables in virtual environments.

Finally, it is also interesting to note that this study used a multi-dimensional scale for trust in a virtual leader; this makes a clear methodological contribution to the existing literature on the study of trust in virtual work contexts, since there is no clear consensus regarding the use of one-dimensional or multi-dimensional scales to measure trust in a virtual leader.

Implications for managementTeam management has become a key element that can facilitate the success of an organization. In this sense, the results of this study contribute to the improvement of the management of work teams through a better understanding of the factors that affect trustworthiness within a team. This paper analyzes the relationships between leaders and subordinates in a virtual work environment with the objective of building trust between the two parties. The conclusions derived from this research should support organizational leaders in improving their relationships with their subordinates in the sense that the latter will be able to establish trusting relationships with their leaders. In this sense, the results of this study can be interpreted as a point of reference for virtual team leaders seeking to build an efficient and committed work team. More specifically, the image of the team leader transmitted through the channels of communication (profiles, video conferences, etc.) should emphasize the physical attractiveness of the leader, since this may reinforce trust among the subordinates. On the other hand, virtual leaders must also be able to develop and transmit a certain degree of empathy with their subordinates, as well as behave fairly toward them.

The results are also interesting from the point of view of the implementation and management of virtual teams within the areas of marketing and market research. High value-added functional departments, such as new product development where there is normally a spatial separation between the different processes, should establish processes for selecting leaders that comply with the above-mentioned characteristics to help build trust among their subordinates and thereby increase the probabilities of success. Similarly, sales force management is also a functional area in which virtual teams are being widely implemented, therefore and in order to build a relationship based on trust with the team, leaders should be able to adapt their leadership style depending on the characteristics of their subordinates and the nature of the tasks.

Future researchFirst, it would be interesting to analyze the determinants of trust in the leader in greater detail. In fact, it is reasonable to believe that aspects such as the personal traits of each individual significantly affect the trust that subordinates grant their leader.

Second, it would be interesting to replicate the study with a sample that includes a wider diversity of nationalities. Given that individual behavior varies greatly in different parts of the world, it would be interesting to analyze possible differences in the antecedents of trust among subordinates of different cultural backgrounds.

Third, in the future it would be interesting to analyze not only the antecedents of trust in the leader but also the effects that are derived from building that trust. More specifically, it would be interesting to analyze the relationship between the trust in the leader and the efficiency that a team achieves at a social level. Furthermore, future research should examine the influence of other characteristics of the leader. It would be interesting to consider the more emotional aspect of the leader-subordinate relationship by evaluating the emotions that arise from such a relationship.

Finally, as previously mentioned, it is very important to further examine the moderating effect that can be exerted by the style of leadership.

Conflict of interestsThe authors declare no conflict of interest.

The authors gratefully acknowledge financial support from the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness (ECO2012-36031) and the Aragón Government (S-46).