The purpose of this study is to investigate the relationship between managerial beliefs regarding social media and the subsequent adoption of these tools by exporting companies, and the moderating effect of export dependence measured by export intensity in those relationships. To accomplish this objective we use data from a Web-based survey distributed (by e-mail) to export managers or CEOs of Spanish exporting firms from the ICEX (Spanish Institute for Foreign Trade) database. Our results show that Managers’ beliefs about social media capabilities for dealing with foreign customers directly influence managerial attitudes toward and intention to use social media, and also indirectly on the intention to use them through the attitude. Then, the intention to use these applications increases their final usage by exporting firms. Export dependence of the company moderates all these relationships, being stronger with a higher export intensity.

El objetivo de este estudio es investigar la relación entre las creencias gerenciales en relación a los medios sociales y la subsiguiente adopción de dichas herramientas por parte de las empresas exportadoras, así como el efecto moderador de la dependencia de la exportación, calibrado mediante la intensidad exportadora en dichas relaciones. Para lograr este objetivo, utilizamos los datos de una encuesta basada en web y distribuida por correo electrónico a los gerentes o a los directores ejecutivos de las empresas exportadoras españolas de la base de datos del ICEX (Instituto Español de Comercio Exterior). Nuestros resultados reflejan que las creencias de los gestores acerca de las capacidades de los medios sociales, en cuanto al trato con los clientes extranjeros, tienen una influencia directa sobre las actitudes gerenciales frente al uso y a la intención de utilizar los medios sociales, y una influencia indirecta sobre la intención de hacer uso de dichos medios a través de la actitud. Por tanto, la intención de utilizar estas aplicaciones incrementa su uso final por parte de las empresas exportadoras. La dependencia de la exportación por parte de la empresa modera todas estas relaciones, acrecentándose cuando la intensidad exportadora es más elevada.

While social media have become a primary customer information source about products and/or services for many of their users, they are outside the traditional marketing communication domain and, therefore, beyond the full control of marketers. Thus, there is evidence that customer-generated content plays an increasingly important role in the consumer's decision-making process (Constantinides, Lorenzo, & Gómez, 2008). Likewise, some recent studies have already investigated the way social-media technology usage is currently contributing to improve customer-relationship management (Trainor, Andzulis, Rapp, & Agnihotri, 2014) and organizational performance (Carmichael, Palacios-Marques, & Gil-Pechuan, 2011). As a result, online marketing management is claiming an increasing portion of marketers’ attention and corporate budgets.

Many authors agree that information technology (IT), and mostly the Internet, have become one of the most important tools for conducting international business and marketing activities (Sinkovics, Sinkovics, & Jean, 2013). In particular, IT-based capabilities have been found to be especially crucial in promoting the emergence of international new ventures and/or facilitating small and medium-sized enterprise (SME) internationalization (Loane, 2006; Mathews & Healym, 2007; Pezderka, Sinkovics, & Jean, 2012; Zhang, Sarker, & Sarker, 2013). In addition, many companies currently rely on ITs and the Internet for improving international supply-chain co-ordination, relationship learning, customer-service management, and firm performance (Trainor et al., 2014).

Social media (tools that enable online exchange of information through conversation and interaction) is emerging as an important technology for business strategy. Unlike traditional IT, social media manage the content of the conversation or interaction as an information artifact in the online environment (Yates & Paquette, 2011). Some authors also highlight their potential influence on international business and export marketing strategies (Berthon, Pitt, Plangger, & Shapiro, 2012; Okazaki & Taylor, 2013), as these applications may help break down barriers of time and distance between the supply and demand sides (Constantinides et al., 2008). Therefore, attending the benefits of social media to break down barriers of time and distance, we assume that social media could assist exporting firms by reducing market lag through real-time and synchronous exchange of knowledge.

Social media mainly differences from other kind of technologies in the fact that these medias employ mobile and web-based technologies to create highly interactive platforms via which individuals and communities share, co-create, discuss, and modify user-generated content (Gagliardi, 2013; Kietzmann, Hermkens, McCarthy, & Silvestre, 2011). In addition, social media have introduced new customer-centric tools that enable customers to interact with others in their social networks and with businesses that become network member (Kietzmann et al., 2011). These technologies have the potential to provide greater access to customer information either directly through firm-customer interactions or indirectly through customer-customer interactions.

However, in spite of the great potential of social media, especially for export-oriented companies, to-date very limited academic attention has been paid to examining the relationship between managers’ beliefs about social media and its adoption among exporting firms. This study aims at filling part of this research gap by answering two research questions:

RQ1: What is the relationship between managerial beliefs regarding social media and the subsequent adoption of these tools by exporting companies? and

RQ2: Does the export dependence, measured by export intensity, moderate this relationship?

To answer these questions, the current research examines the effect of social media expected capabilities and managerial usage behavior through incorporating the Resource-Based View (RBV) framework and two main constructs of the Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA) (attitude and behavior). The RBV can be applied to investigate how a firm's powerful resource base enables companies obtain advantages. Specifically, related with our topic, many researchers have studied how technological resources and information technology (IT) capability can serve as a source of sustainable competitive advantage for export companies (Filipescu, Prashantham, Rialp, & Rialp, 2013; Pla-Barber & Alegre, 2007). In this sense, several researchers set out that a company's success in foreign markets depends heavily on its capacity to adapt to new developments such as ITs and Internet-related capabilities (Loane, 2006; Sinkovics et al., 2013). In our research, we will focus on studying the development of these capabilities through the use of a specific technology, Social Media, since these tools present several advantages for conducting international activities. However, the expected benefits from the use of Social Media need first to be recognized by managers who will be willing to use these media in their business strategy. Therefore, we connect this RBV with the TRA, which is a well-known model for predicting and explaining individual behavior. Moreover, other models that explain the adoption of any kind of technology, for example, the Technology Adoption Model (Davis, 1989; Davis, Bagozzi, & Warshaw, 1989), are based in this TRA model. The most common variables included in these model that explain the adoption behavior are the attitude, intention to use and use of the technologies, and they explain how the individual beliefs determine to perform a specific individual behavior (Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975).

The research objectives are to explain the adoption of social media applications as part of the marketing toolbox of exporting companies and identify the main parameters influencing the adoption process, as well as investigate if the export dependence measured by export intensity exerts a moderating role in the analyzed relationships. To achieve this goal, we will empirically focus on Spanish exporting companies. Our results show that Managers’ beliefs about social media capabilities for dealing with foreign customers directly influence managerial attitudes toward and intention to use social media, and also indirectly on the intention to use them through the attitude. Then, the intention to use these applications increases their final usage by exporting firms. Export dependence of the company moderates all these relationships, being stronger with a higher export intensity.

For accomplishing the mentioned purposes, the paper is organized as follows: “Theoretical foundation of the study” section provides the theoretical foundation of the study. More specifically, this section develops the social media and foreign customer–company interaction and presents the theoretical framework, the research model, and the hypotheses to be tested. “Methodology” section is focused on the methodology and describes the data collection and the measurement of constructs and variables. “Results” section presents the specific technique employed to test the hypotheses, the different steps followed and the results of our analysis. Finally, “Discussion and conclusions” section contains the discussion and conclusions, as well as the implications, contributions, limitations and future research lines.

Theoretical foundation of the studySocial media and foreign customer–company interactionInternet provides companies new ways to develop international business through faster access to market and competitor information (Mathews & Healym, 2007). Using the Internet, companies can considerably reduce international business costs. Furthermore, it offers the possibility of providing information targeted to specific stakeholders and to obtain feedback from them (Biloslavo & Trnavcevic, 2009). Internet has also served for other purposes such as: social bonding, online service quality, external information acquisition for strategic decision-making, customer relationship management, market research, online word-of-mouth, and business intelligence (Lim, Zegarra Saldaña, & Zegarra Saldaña, 2011). In fact, with the emergence of social media, companies now have a greater ability to take advantage of international market-growth opportunities, exchange of collective knowledge and accumulate social capital; so this phenomenon has specific and unique implications for international marketing strategy (Berthon et al., 2012; Okazaki & Taylor, 2013).

It is worth noting that customers have adopted social media to connect with others and now expect the same level of interactivity with companies (Berthon et al., 2012; Trainor et al., 2014). This shift in expectations is challenging businesses to facilitate more customer–company interaction by deploying new technologies and capabilities (Trainor et al., 2014).

Theories of referenceThe Resource-Based View has become an influential perspective in international business (IB) research (Peng, 2001) and has been applied, for example, to investigate how a firm's powerful resource base enables SMEs to export more successfully (e.g., Knight & Cavusgil, 2004; Stoian et al., 2012; Zucchella, Palamara, & Denicolai, 2007).

RBV focuses on the way firms adopt strategies based on their strategic resources and capabilities to gain a sustainable competitive advantage and superior firm performance (Barney, 1991). In this sense, technological resources and IT capability, in particular, can serve as a source of sustainable competitive advantage both domestically and abroad (Filipescu et al., 2013; Pla-Barber & Alegre, 2007).

Bharadwaj, Sambamurthy, and Zmud (1999) define IT capability as ‘a firm's ability to acquire, deploy and leverage its IT-related resources in combination with other resources and capabilities in order to achieve business objectives’ (p. 379). Therefore, IT capability is composed of technical skills and information technologies within the whole firm, as well as other managerial resources (e.g., Bharadwaj et al., 1999; Bharadwaj, 2000).

Several researchers set out that a company's success in foreign markets depends heavily on its capacity to adapt to new developments such as ITs and Internet-related capabilities (Loane, 2006; Sinkovics et al., 2013). The explosive growth and low cost of ITs and the Internet (Loane, 2006) has enabled companies to connect with people and locations all over the world. They have strengthened international business relations by increasing the efficiency of market transactions and promoting access to information easily and faster (Mathews & Healym, 2007; Pezderka et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2013). According to Pezderka et al. (2012), ‘those companies that develop superior capabilities in terms of communication with customers, relationship-building, reaching potential customers, bypassing costly physical presence in foreign markets, market research, being a front-runner in employing advanced export management technology, and cost reduction through Internet deployment will experience enhanced export performance’ (p. 9).

In a similar vein, Social Media Capabilities (SMCs) can be seen as an integrated set of strategic resources and capabilities that can create, through the use of social media applications, sound competitive advantages and superior firm performance based upon a more effective information management (Carmichael et al., 2011; Trainor et al., 2014). Therefore, SMCs are potentially important for conducting international activities, as these capabilities may improve communication with foreign customers, reducing or even eliminating distances. However, these expected benefits from SMCs need first to be recognized by managers who will be willing to adopt social media in their managerial activity.

In the last twenty years, several researchers have focused on identifying variables that influence acceptance behavior regarding ITs. TRA is a well-known model for predicting and explaining individual behavior (Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975). TRA asserts that behavioral intentions to perform the behavior determine individual behavior, and that behavioral intentions are jointly determined by individual attitudes regarding behavior. The attitude is ‘a learned predisposition to respond favorably or unfavorably toward something’ (Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975, p. 216). Fishbein and Ajzen (1975) proposed that attitudes are learned, and therefore are dynamic. They can and do change with experience. These predispositions are assumed to also predispose one to certain actions and behaviors.

Hypotheses and research modelAccording to the expectation-value theory, individual attitudes toward a specific behavior are a function of salient beliefs and evaluations of behavior outcomes. In terms of ITs adoption process by potential users within firms, attitude toward adopting (or continuing to use) a given IT is generated by the individual's salient beliefs about the consequences of adopting (or continuing to use) the IT (behavioral beliefs) and evaluation of these consequences. Thus, attitude is derived by the strength of the person's beliefs that adopting (or continuing to use) the IT will lead to certain consequences, each weighted by the evaluation of each belief's behavioral consequences (Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975).

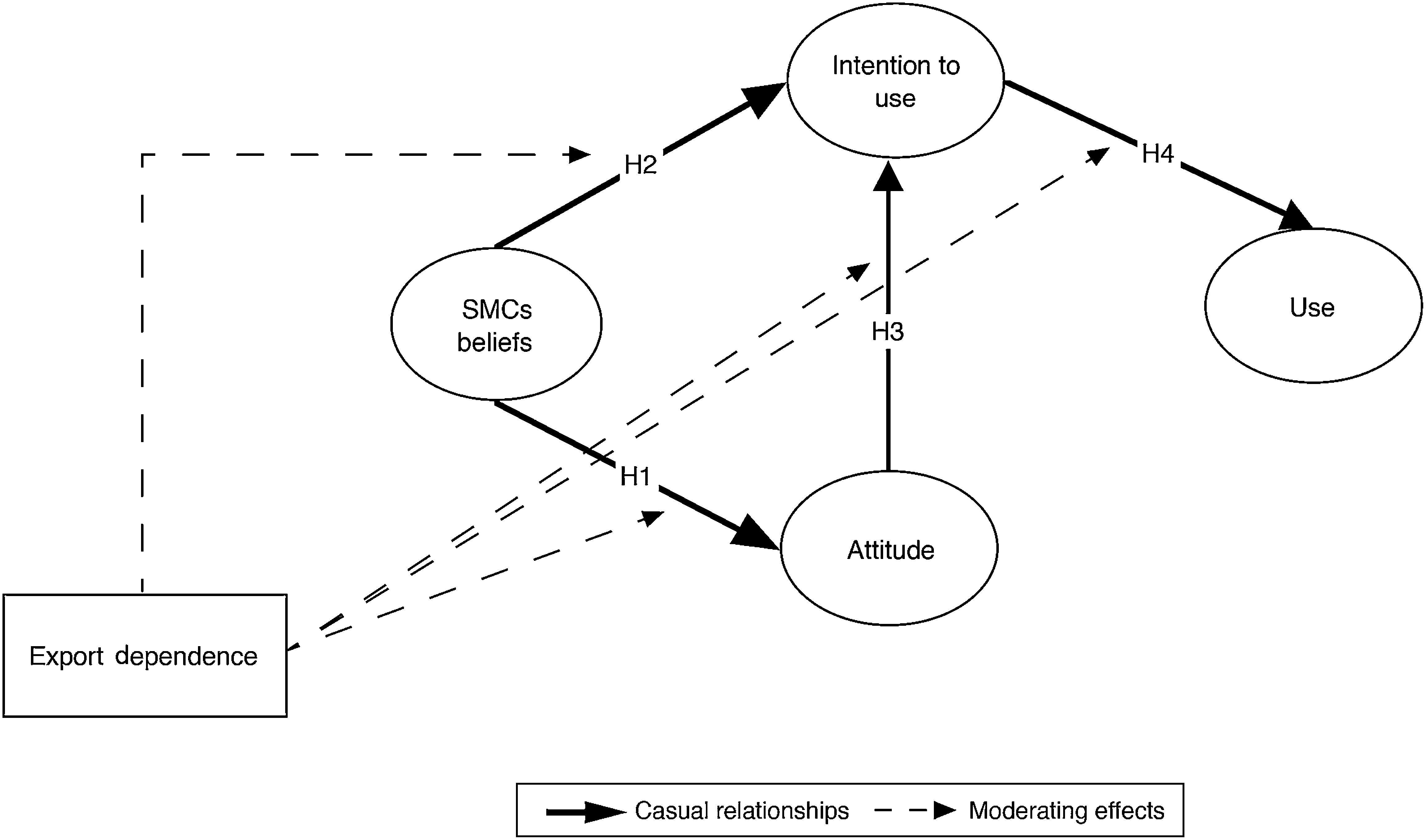

Accordingly, our assumption is that the TRA model can also be adapted to explain how the managers’ beliefs regarding the expected potential of social media capabilities to create competitive advantage when dealing with foreign customers may impact on their attitude toward and intentions to use social media, especially in export-oriented firms. In particular, the more positive their managers’ perceptions about social media capabilities for their firms, the greater their attitude and intention to use social media will be. That is, managers’ beliefs about expected goodness of social media capabilities can predict the managerial attitude toward social media and the intention to use them. Then, we propose the following hypotheses:Hypothesis 1 Managers’ SMCs beliefs have a positive effect on their attitude toward social media. Managers’ SMCs beliefs have a positive effect on their intention to use social media.

The relationship between attitude and intention to use an online system has been analyzed in different contexts: Adoption of information technology and information systems, web, e-mail, e-commerce, social media and social networking sites (e.g., Davis, 1989; Davis et al., 1989). This strong and widespread positive effect of the attitude on the intention to use IT-related technologies, either by individual users as well as by firm employees, leads us to think that the same mechanics will operate in the relationship between attitude and intention to use social media in a managerial context. Then:Hypothesis 3 The managerial attitude toward social media has a positive effect on the intention to use these applications.

Some TRA and Technology Acceptance Model-based studies have included the current use of technology (e.g., Davis, 1989), and others have introduced the concept of intention to use (e.g., Luarn & Li, 2005). Other authors have applied both concepts, and suggest a causal relationship between them (e.g., Davis et al., 1989). In this line, we have introduced both variables, as we believe that the intention to use or continue to use acts as a mediator between the effect exerted by SMCs beliefs and final use by managers. Therefore:Hypothesis 4 The managerial intention to use social media has a positive effect on the final use of these applications.

According to López Rodríguez and García Rodríguez (2005), international markets are characterized by a greater competitive pressure. Therefore, firms that dedicate part of their efforts to markets abroad have intensified their search for competitive advantages (Hitt, Hoskisson, & Kim, 1997), in order to confront the competition and survive in these markets.

From the perspective of RBV, generating and sustaining competitive advantages resides in the set of strategic resources and capabilities available to the firm (Barney, 1991; López Rodríguez & García Rodríguez, 2005). Among intangible resources, technological resources are particularly significant; these provide the firm with an innovative capacity and are important for the creation of competitive advantages, especially those based on differentiation that give a firm a superior competitiveness to act in international and global markets (López Rodríguez & García Rodríguez, 2005).

Exports intensity is understood as the ratio of total exports to sales turnover. Conflicting findings with respect to exports and adoption on advanced technologies have been reported in the literature. Several reasons have been cited for conflicting results. For example, if the domestic markets are not protected, it becomes imperative for firms to upgrade technology for the survival in the domestic market. In that case, technological advancement may not be related to the export intensity of firms (Lal, 2005). However, some studies have demonstrated that companies with higher export intensity have a higher level of ICT adoption (e.g., Haller & Traistaru-Siedschlag, 2007). In a similar vein, those companies who have a higher export dependence should have a higher use and a more positive attitude toward these applications, since these media have an influence on international business and export marketing strategies (Berthon et al., 2012; Okazaki & Taylor, 2013), as these applications may help break down barriers of time and distance between the supply and demand sides (Constantinides et al., 2008).

On the other hand, the technology and innovation management literature provides evidence of a positive relationship between innovation and export intensity (Pla-Barber & Alegre, 2007; Roper & Love, 2002). Likewise, managerial commitment expressed in terms of interest in and willingness to allocate sufficient resources to exporting, and the extent of international involvement and experience may significantly influence in all the steps related to the export process and success (Prasad, Ramamurthy, & Naidu, 2001). Therefore, in this study, we want to analyze the relationship between export intensity and the attitudes and behavior toward social media. More precisely, and following Prasad et al. (2001), in this research a firm's degree of export dependence, measured by export intensity, is used as a surrogate for international involvement/experience and management's willingness to commit resources to exporting. As recognized by Chi and Sun (2013), as firms become more rely on export for their sales and profits or, in other words, they are more export dependent (Cadogan, Paul, Salminen, Puumalainen, & Sundqvist, 2001), they are prone to allocate greater resources to export market information gathering and dissemination. That is the reason why it is logical to expect that, in the case of exporting companies, the relations among beliefs about their social media capabilities, attitudes toward social media, intention to use and use of these tools are likely to be higher for firms with a greater degree of export dependence. In other words, the moderator effect of export intensity would make that the relationships be stronger in these companies with higher export intensity. Thus, we hypothesize:Hypothesis 5 Firms’ degree of export dependence has a significant moderating influence on the relationships between SMCs beliefs, attitude toward social media, intention to use social media and the final use of these applications.

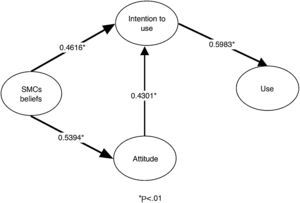

Therefore, considering all of the suggested hypotheses, we establish a logical-causal chain where managers’ beliefs regarding social media capabilities for dealing with foreign customers generate a direct positive attitude toward social media applications. In addition, these beliefs would also directly influence on the managerial intention to use social media, and indirectly through the attitude. Such positive intention to use social media will increase its usage by the exporting company. Finally, we hypothesize that all of these relationships are moderated by the export intensity (Fig. 1).

MethodologyA Web-based survey was distributed to 3060 international and/or general manager in charge of the firm's foreign business activity of Spanish exporting firms in the food sector, beverage sector, consumer goods, raw materials, industrial products and capital goods sectors; from the ICEX (Spanish Institute for Foreign Trade) database by e-mail from March to May 2013. After a second re-call wave, the final valid number of companies in the study is 152. Consistent with the suggestion by Stanton and Rogelberg (2001), we decided to send just two reminder e-mails. As different authors point out, ‘frequent e-mail participation reminders may be perceived as intrusive’ (Michalak & Szabo, 1998, p. 205).

To analysis the possible nonresponse bias, we compared the number of times the Web page with the survey was requested with the number of completed research responses actually received, so we can make a reasonable estimation of active refusals: 1100 times the web page was requested and 152 is the number of completed research responses (152 represent a 13.2% rate of non-refusal, rate that is close to the acceptable range of 15–20% mentioned by Menon, Bharadwaj, & Howell, 1996).

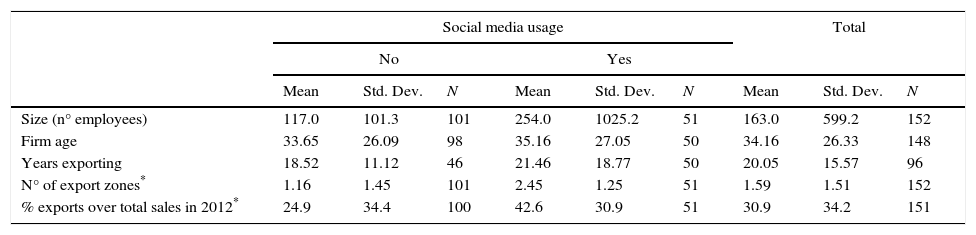

Descriptive information of the firms in the sample is presented in Table 1. In the final sample obtained firms have 163 employees on average (63.5% have fewer than 52 employees), similar percentage than the one obtained by Navarro-García, Arenas-Gaitán, and Rondán-Cataluña (2014), on average the age is 34.16 and the export experience is about 20 years (64.58% have more than 14 years of export activity, similar percentage than the one obtained in the sample of Navarro-García et al. (2014): 61% have more than 15 years of export activity). Furthermore, 59.60% have website, 12.50% develop e-Commerce, and they have profile on approximately 2 social media applications on average.

Descriptive analysis of sampling firms.

| Social media usage | Total | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | ||||||||

| Mean | Std. Dev. | N | Mean | Std. Dev. | N | Mean | Std. Dev. | N | |

| Size (n° employees) | 117.0 | 101.3 | 101 | 254.0 | 1025.2 | 51 | 163.0 | 599.2 | 152 |

| Firm age | 33.65 | 26.09 | 98 | 35.16 | 27.05 | 50 | 34.16 | 26.33 | 148 |

| Years exporting | 18.52 | 11.12 | 46 | 21.46 | 18.77 | 50 | 20.05 | 15.57 | 96 |

| N° of export zones* | 1.16 | 1.45 | 101 | 2.45 | 1.25 | 51 | 1.59 | 1.51 | 152 |

| % exports over total sales in 2012* | 24.9 | 34.4 | 100 | 42.6 | 30.9 | 51 | 30.9 | 34.2 | 151 |

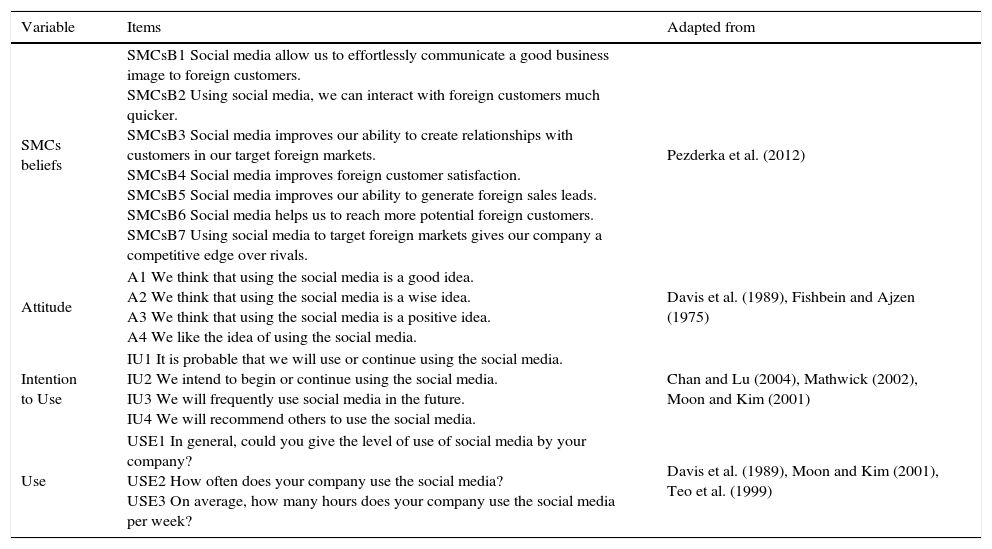

The constructs used in our study were adapted from previous studies and measured by multiple item five-point Likert-type scales (see Table 2).1 In addition to this, at the beginning of the questionnaire, we included a brief description about the objective of the research, definition of Social Media, different uses of these tools in business strategy and the context that we wanted to analyze.

Final items (content validity).

| Variable | Items | Adapted from |

|---|---|---|

| SMCs beliefs | SMCsB1 Social media allow us to effortlessly communicate a good business image to foreign customers. SMCsB2 Using social media, we can interact with foreign customers much quicker. SMCsB3 Social media improves our ability to create relationships with customers in our target foreign markets. SMCsB4 Social media improves foreign customer satisfaction. SMCsB5 Social media improves our ability to generate foreign sales leads. SMCsB6 Social media helps us to reach more potential foreign customers. SMCsB7 Using social media to target foreign markets gives our company a competitive edge over rivals. | Pezderka et al. (2012) |

| Attitude | A1 We think that using the social media is a good idea. A2 We think that using the social media is a wise idea. A3 We think that using the social media is a positive idea. A4 We like the idea of using the social media. | Davis et al. (1989), Fishbein and Ajzen (1975) |

| Intention to Use | IU1 It is probable that we will use or continue using the social media. IU2 We intend to begin or continue using the social media. IU3 We will frequently use social media in the future. IU4 We will recommend others to use the social media. | Chan and Lu (2004), Mathwick (2002), Moon and Kim (2001) |

| Use | USE1 In general, could you give the level of use of social media by your company? USE2 How often does your company use the social media? USE3 On average, how many hours does your company use the social media per week? | Davis et al. (1989), Moon and Kim (2001), Teo et al. (1999) |

All items were measured by five-point Likert-type scales.

Specifically, the SMCs beliefs construct identifies the managerial beliefs about the potential of social media capabilities in order to perform communication tasks or activities, and effectively manage information about foreign customers. The SMCs beliefs scale was developed on the basis of previous work by Pezderka et al. (2012). We simplified the measuring instrument as much as possible by selecting and adapting to the social media context only those attributes related to capabilities for improving the international communication, efficiency of market transactions abroad, satisfaction and loyalty of foreign customers and the development of international network relationships. We obtained a scale of SMCs managerial beliefs with seven items.

The constructs used in our study to measure managerial attitude, intention to use, and firm's use of social media, were adapted from previous studies related to the adoption of IT.

Technique of analysisA structural equation modeling (SEM), specifically partial least squares (PLS), is proposed to assess the measurement and structural model. Although this technique provides few fit measures for the structural model, we have used this technique because is more appropriate for exploratory research and studies with small sample sizes, and because the PLS algorithm shows greater convergence in its simplicity, offering fewer restrictions on the sample size and data normality. In addition, Reinartz, Haenlein, and Henseler (2009) note that PLS is more appropriate when the number of observations is below 250, as in our case.

SmartPLS 2.0 software was used to analyze the data. The stability of the estimates was tested via a bootstrap re-sampling procedure (500 sub-samples).

A PLS model is analyzed in two stages: First, the assessment of the reliability and validity of the measurement model, and second, the assessment of the structural model (Jöreskog & Sörbom, 1993).

ResultsReliability and validity assessmentFirst, following the approach of other studies (e.g., Alegre & Chiva, 2013; Zhou, Barnes, & Lu, 2010), we assessed whether common method bias posed a threat to our data by performing Harman's one-factor test on the items. If there is a substantial amount of common method variance, then either a single factor will emerge from the factor analysis, or one general factor will account for the majority of the covariance among the variables (Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee, & Podsakoff, 2003). In our case, common method bias did not pose a threat to our data.

Secondly, we performed an analysis of the validity and reliability of the scales employed in our model. As one of our objective is to analyze the moderator effect of export intensity in the relationships proposed, we separated the companies into two groups for the moderator: companies with a high export intensity and companies with a low export intensity. Our questionnaire asked export intensity as export sales as percentage of total sales. Therefore, we have divided the scores at the fiftieth percentile of the total group, and we assigned the companies to the Group 1 if they have a value under the fiftieth percentile (low export intensity), and to the Group 2 if they have a value above the fiftieth percentile (high export intensity). Therefore, we will analyze the validity and reliability of the scales for the three models (Total, Group 1 and Group 2).

The scales’ development was founded on the review of the most relevant literature, thus assuring the content validity of the measurements instruments (Cronbach, 1971). Although due the lack of valid scales adapted to Web 2.0 adoption, it was necessary to adapt the initial scales (Table 2).

To analyze the reliability of the constructs, we first conducted an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) with SPSS software. The consideration of multiple items for each construct increases construct reliability (Terblanche & Boshoff, 2008). EFA confirmed the unidimensionality of the four constructs considered in the model. The item-total correlation is above the minimum of 0.3 recommended by Nurosis (1993) for all constructs in the sample used. Cronbach's alpha (α) exceeded the recommendation of 0.70 suggested by Nunnally and Bernstein (1994).

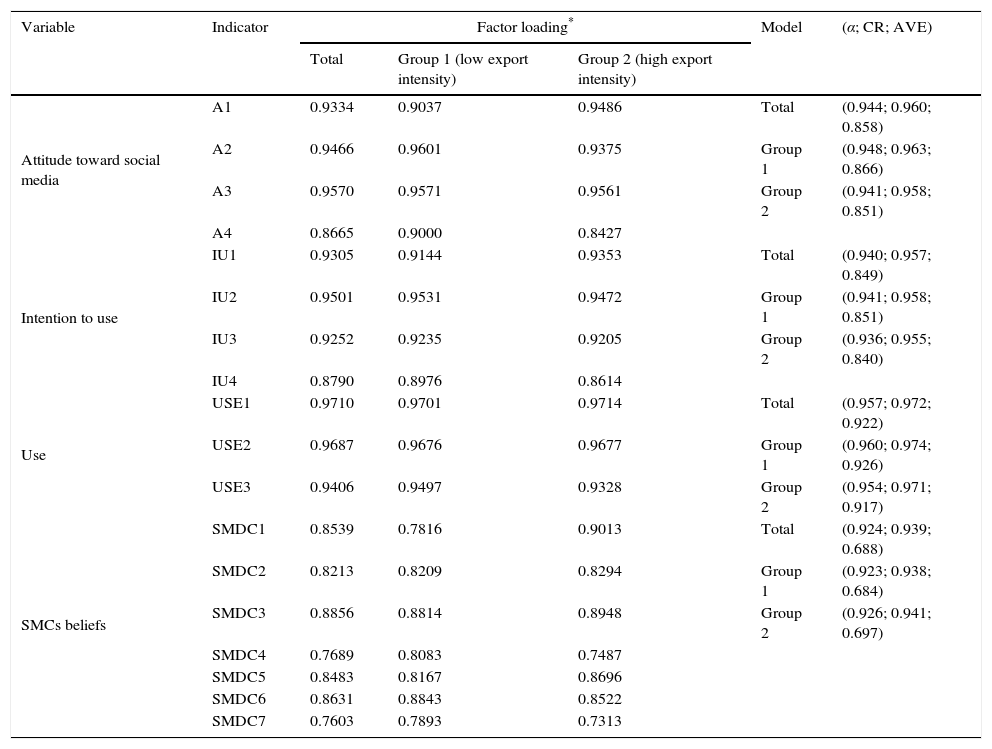

The results of the PLS are reported in Table 3. Generally, a CR of at least 0.60 is considered desirable (Bagozzi & Yi, 1988; Fornell & Larcker, 1981). This requirement is fulfilled for every factor in the three models: Total model, Group 1 (companies with low export intensity, below the median) and Group 2 (companies with high export intensity, above the median). The average variance extracted (AVE) was also calculated for each construct; the resulting AVE values were greater than 0.50 (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). Therefore, the four constructs demonstrated acceptable levels of reliability.

Internal consistency and convergent validity.

| Variable | Indicator | Factor loading* | Model | (α; CR; AVE) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Group 1 (low export intensity) | Group 2 (high export intensity) | ||||

| Attitude toward social media | A1 | 0.9334 | 0.9037 | 0.9486 | Total | (0.944; 0.960; 0.858) |

| A2 | 0.9466 | 0.9601 | 0.9375 | Group 1 | (0.948; 0.963; 0.866) | |

| A3 | 0.9570 | 0.9571 | 0.9561 | Group 2 | (0.941; 0.958; 0.851) | |

| A4 | 0.8665 | 0.9000 | 0.8427 | |||

| Intention to use | IU1 | 0.9305 | 0.9144 | 0.9353 | Total | (0.940; 0.957; 0.849) |

| IU2 | 0.9501 | 0.9531 | 0.9472 | Group 1 | (0.941; 0.958; 0.851) | |

| IU3 | 0.9252 | 0.9235 | 0.9205 | Group 2 | (0.936; 0.955; 0.840) | |

| IU4 | 0.8790 | 0.8976 | 0.8614 | |||

| Use | USE1 | 0.9710 | 0.9701 | 0.9714 | Total | (0.957; 0.972; 0.922) |

| USE2 | 0.9687 | 0.9676 | 0.9677 | Group 1 | (0.960; 0.974; 0.926) | |

| USE3 | 0.9406 | 0.9497 | 0.9328 | Group 2 | (0.954; 0.971; 0.917) | |

| SMCs beliefs | SMDC1 | 0.8539 | 0.7816 | 0.9013 | Total | (0.924; 0.939; 0.688) |

| SMDC2 | 0.8213 | 0.8209 | 0.8294 | Group 1 | (0.923; 0.938; 0.684) | |

| SMDC3 | 0.8856 | 0.8814 | 0.8948 | Group 2 | (0.926; 0.941; 0.697) | |

| SMDC4 | 0.7689 | 0.8083 | 0.7487 | |||

| SMDC5 | 0.8483 | 0.8167 | 0.8696 | |||

| SMDC6 | 0.8631 | 0.8843 | 0.8522 | |||

| SMDC7 | 0.7603 | 0.7893 | 0.7313 | |||

α: Cronbach's Alpha; CR: composite reliability; AVE: average variance extracted.

Convergent validity is verified by analyzing the factor loadings and their significance. The individual item loadings in our models are higher than 0.6 (Bagozzi & Yi, 1988), and the average of the item-to-factor loadings are higher than 0.7 (Hair, Black, Babin, Anderson, & Tatham, 2006). In addition, we have checked the significance of the loadings with a re-sampling procedure (500 sub-samples) for obtaining t-statistic values. They are all significant (p<.001). These findings provide evidence supporting the convergent validity of the indicators for the three models.

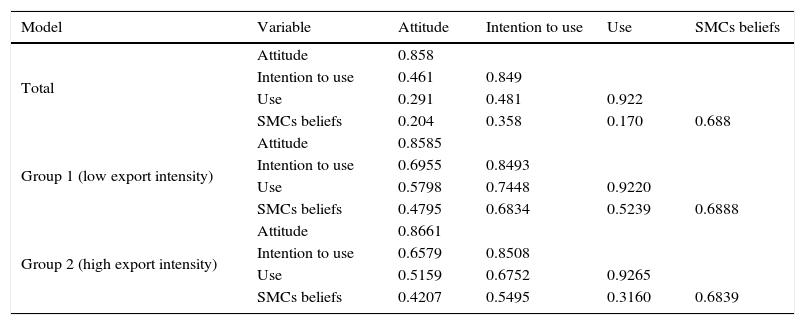

This research adopted Fornell and Larcker (1981) criteria of discriminant validity to examine whether the square root of the AVE for each construct exceeds the correlation shared between the construct and other constructs in the model. As shown in Table 4, all diagonal values exceeded the inter-construct correlations, thereby demonstrating adequate discriminant validity of all constructs for every model.

Discriminant validity of the theoretical construct measures.

| Model | Variable | Attitude | Intention to use | Use | SMCs beliefs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Attitude | 0.858 | |||

| Intention to use | 0.461 | 0.849 | |||

| Use | 0.291 | 0.481 | 0.922 | ||

| SMCs beliefs | 0.204 | 0.358 | 0.170 | 0.688 | |

| Group 1 (low export intensity) | Attitude | 0.8585 | |||

| Intention to use | 0.6955 | 0.8493 | |||

| Use | 0.5798 | 0.7448 | 0.9220 | ||

| SMCs beliefs | 0.4795 | 0.6834 | 0.5239 | 0.6888 | |

| Group 2 (high export intensity) | Attitude | 0.8661 | |||

| Intention to use | 0.6579 | 0.8508 | |||

| Use | 0.5159 | 0.6752 | 0.9265 | ||

| SMCs beliefs | 0.4207 | 0.5495 | 0.3160 | 0.6839 |

Diagonal elements are the square root of average variance extracted (AVE) between the constructs and their measures.

Off-diagonal elements are correlations between constructs.

Based on all criteria, it was concluded that the measures in the study provided sufficient evidence of reliability and validity for the three models.

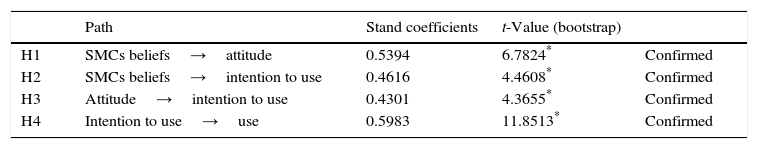

Structural modelBeing evaluated the psychometric properties of measurement instrument, we proceeded to estimate the structural model, using PLS and the same criteria for determining the significance of the parameters (bootstrapping of 500 sub-samples).

To assess the predictive ability of the structural model we followed the approach proposed by Falk and Miller (1992) that the R2 value (variance accounted for) of each of the dependent constructs exceed the 0.1 value. Table 5 shows that the R2 values in the dependent variables are higher than the critical level mentioned. Another test applied was the Stone-Geisser test of predictive relevance (Q2). This test can be used as an additional assessment of model fit in PLS analysis (Geisser, 1975; Stone, 1974). The Blindfolding technique was used to calculate de Q2. Models with Q2 greater than zero are considered to have predictive relevance (Chin, 1988). In our case Q2 is positive for all predicted variables.

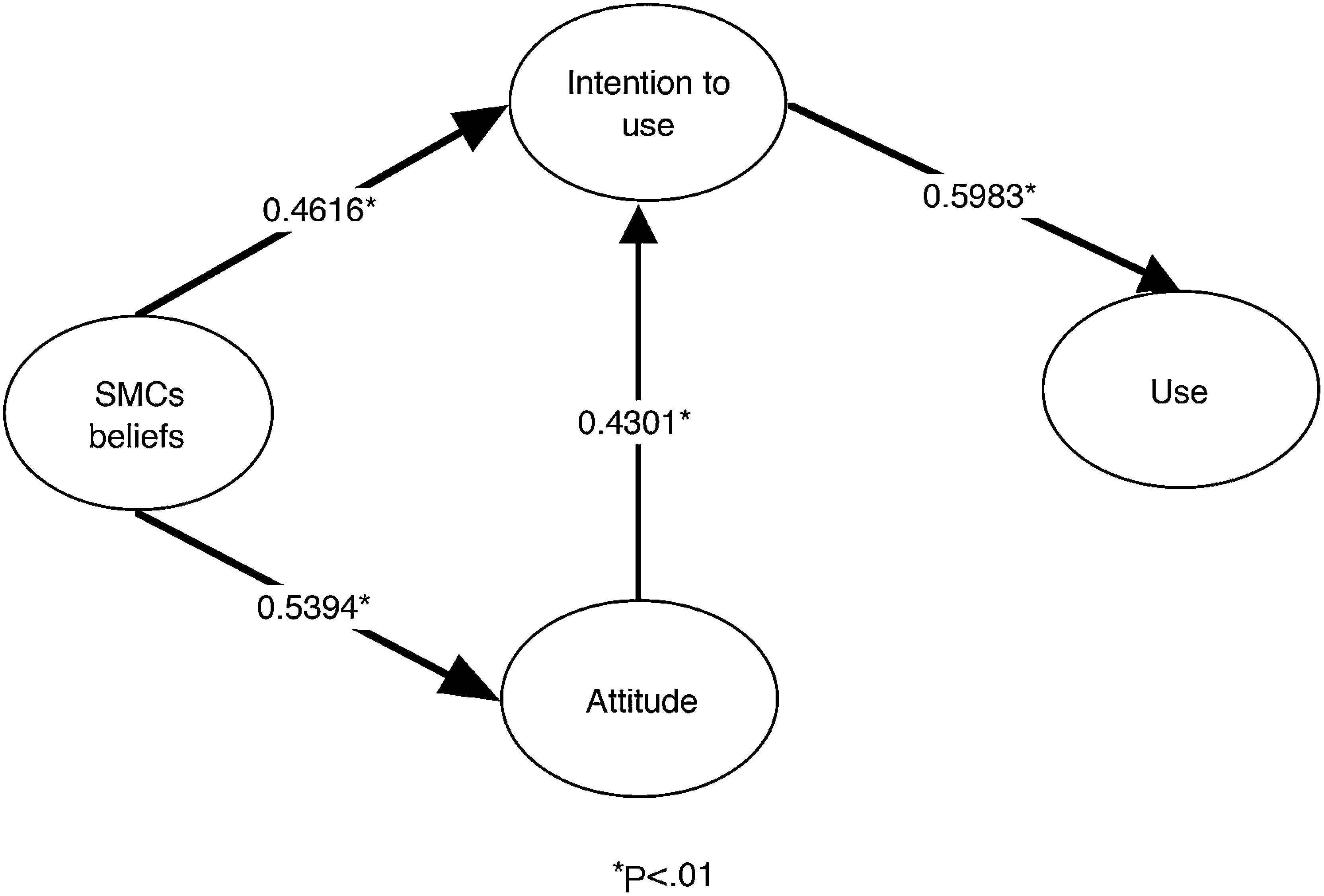

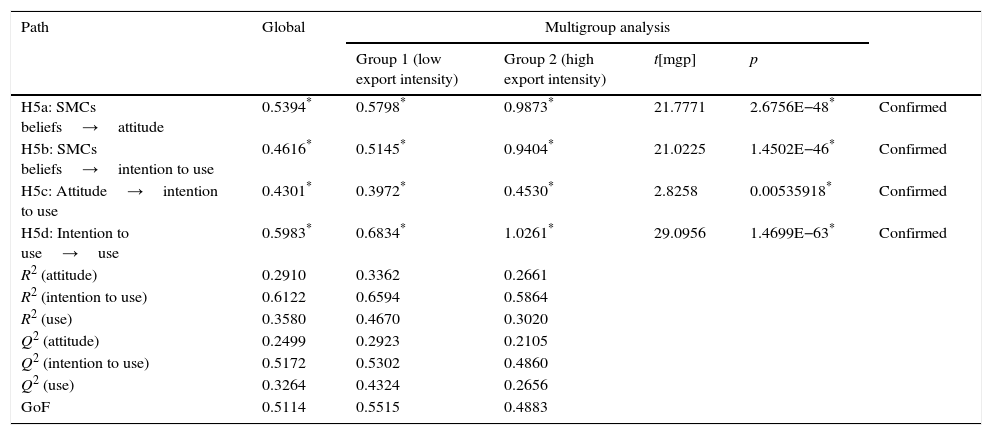

Hypotheses testing.

| Path | Stand coefficients | t-Value (bootstrap) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | SMCs beliefs→attitude | 0.5394 | 6.7824* | Confirmed |

| H2 | SMCs beliefs→intention to use | 0.4616 | 4.4608* | Confirmed |

| H3 | Attitude→intention to use | 0.4301 | 4.3655* | Confirmed |

| H4 | Intention to use→use | 0.5983 | 11.8513* | Confirmed |

R2 (attitude)=0.291; R2 (intention to use)=0.6122; R2 (use)=0.3580.

Table 5 and Fig. 2 show a synthesis of the results obtained for the causal hypothesis testing. Consistent with Chin (1988), bootstrapping (500 re-samples) was used to generate t-values. Support for each general hypothesis can be determined by examining the sign and statistical significance of the t-values. In the overall model, the results obtained allow us to state that the logical-causal chain theoretically suggested is observed in the available sample of exporting firms. Therefore, managers’ beliefs about the adequacy of social media capabilities for dealing with foreign customers generate both a positive managerial attitude and a greater intention to use these applications. In addition, this positive attitude also has a favorable effect upon managerial intention of using social media which, in its turn, increases the usage of all of these applications within the firm.

Multigroup analysisOur last hypothesis suggested that firms’ degree of export dependence has a significant moderating influence on the relationships between SMCs beliefs, attitude toward social media, intention to use social media and the final use of these applications. Authors as Chi and Sun (2013) consider that as firms become more rely on export for their sales and profits, they are prone to allocate greater resources to export market information gathering and dissemination. So, the moderator effect of export intensity would make that the relationships be stronger in these companies with higher export intensity.

Although there are different procedures to test moderating effects in PLS path models (see Henseler & Fassott, 2010),2 we have followed a two steps process already used in the academic literature (Chin, 2000; Keil et al., 2000): first, the model was run separately for each subgroup (Group 1: companies with a low export intensity; Group 2: companies with a high export intensity). This PLS model is analyzed and interpreted in two stages for the two groups, as the global model. First, the adequacy of the measures was assessed by evaluating the reliability and validity of the constructs. Then, the structural model was appraised.

The Blindfolding technique was used to calculate de Q2 and Bootstrap to estimate the precision of the PLS estimates. Thus, 500 samples sets were created in order to obtain 500 estimates for each parameter in the PLS model for each group. As all values of R2 exceed the 0.1 value and all Q2 are positive for both groups, the relations in the models have predictive relevance.

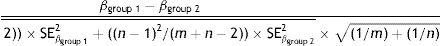

Second, the multigroup path coefficient differences were examined based on the procedure suggested by Keil et al. (2000) and Chin (2000). These authors suggest apply an unpaired samples t-test to the group-specific model parameters using the standard deviations of the estimates resulting from bootstrapping. The parametric test uses the path coefficients and the standard errors of the structural paths calculated by PLS with the samples of the two groups, using the following expression of t-value for multigroup comparison test (1) (see Chin, 2000) (m=group 1 sample size and n=group 2 sample size):

This statistic follows a t-distribution with m+n−2 degrees of freedom. The subsample-specific path coefficients are denoted as β, the sizes of the subsamples as m and n, and the patch coefficient standard errors as resulting from bootstrapping as SE.

As shown in Table 6, the impact of moderating variable on the proposed relationships (Hypothesis 5) was significant, since all t-value for multi-group comparison are significant at a level of 0.01. In other words, whether the firms have high export intensity or low export intensity have impact on the proposed hypothesis, being stronger these relationships as higher export intensity.

Hypotheses testing for a moderating effect of export intensity.

| Path | Global | Multigroup analysis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1 (low export intensity) | Group 2 (high export intensity) | t[mgp] | p | |||

| H5a: SMCs beliefs→attitude | 0.5394* | 0.5798* | 0.9873* | 21.7771 | 2.6756E−48* | Confirmed |

| H5b: SMCs beliefs→intention to use | 0.4616* | 0.5145* | 0.9404* | 21.0225 | 1.4502E−46* | Confirmed |

| H5c: Attitude→intention to use | 0.4301* | 0.3972* | 0.4530* | 2.8258 | 0.00535918* | Confirmed |

| H5d: Intention to use→use | 0.5983* | 0.6834* | 1.0261* | 29.0956 | 1.4699E−63* | Confirmed |

| R2 (attitude) | 0.2910 | 0.3362 | 0.2661 | |||

| R2 (intention to use) | 0.6122 | 0.6594 | 0.5864 | |||

| R2 (use) | 0.3580 | 0.4670 | 0.3020 | |||

| Q2 (attitude) | 0.2499 | 0.2923 | 0.2105 | |||

| Q2 (intention to use) | 0.5172 | 0.5302 | 0.4860 | |||

| Q2 (use) | 0.3264 | 0.4324 | 0.2656 | |||

| GoF | 0.5114 | 0.5515 | 0.4883 | |||

This research has tested a TRA-based model of social media adoption by exporting firms. In particular, this research has assessed the extent to which managers’ beliefs, attitudes, and intention to use social media do increase their usage among Spanish exporting firms.

The results obtained in the empirical section allow us to confirm all the hypotheses suggested and answer the two research questions initially established: what is the relationship between managerial beliefs regarding social media and the subsequent adoption of these tools by exporting companies? and, does the export dependence, measured by export intensity, moderate this relationship? We have seen that managers’ beliefs about the adequacy of social media capabilities for dealing with foreign customers generate a positive managerial attitude and a greater intention to use these applications. In addition, this positive attitude also has a favorable effect upon managerial intention of using social media that increases the usage of all of these applications within the firm. Therefore, as in previous research, we have also demonstrated that attitude has an intervening effect on the relation between beliefs and intention (e.g., Cheng, Lam, & Yeung, 2006). Actually, beliefs are a key factor in the adoption process and use of any IT. This research specifically offers insight of the influence that the beliefs of one person can exert, in this case the manager's beliefs, in the adoption and use of social media. In addition, for Spanish exporting companies, the adoption of social media is conditioned by the export dependence of the firm, measured by its export intensity, as they give a greater importance of these tools when the importance of international versus domestic market is also higher. Probably, the moderating effect of export intensity on the attitude and using behavior of social media, is due to when the weight of international business is very important, companies want to keep their competitive position outside, therefore is key to have access to the customer needs, and stakeholders needs in general. Social media are the means by which consumers can express their needs and thoughts, and may be an essential tool in maintaining relationships and bidirectional communication with the different stakeholders.

Implications and contributionsFrom an academic standpoint, the main contribution of this research is to develop the managers’ SMCs beliefs construct by measuring their beliefs about the potential of social media applications to better deal with customers abroad. In our opinion, this research generates a new, promising area of inquiry in the Internet and export marketing interface, focused on social media, and opens up lines for further research on it.

From a practitioner's point of view, considering the obtained results, we can generally affirm that not only is it a question of having a given technological capability ‘available’, but also firms’ decision-makers must have a positive attitude and the willingness to use it. Thus, firm capabilities may constitute a source of a sustainable competitive advantage and, as a consequence, a determinant of a superior firm performance if managers have strong beliefs about their efficacy for their firms and act accordingly. For instance, in our opinion, the establishment of a specialized area in charge of Web 2.0 implementation within the firm would constitute a very interesting investment for export-oriented companies. In addition, main consequences related to the firm's human resources policy should be considered.

Nevertheless, most companies still have a long way to go to learn about how to correctly implement and fully exploit social media. They can easily have a Facebook or Twitter account but, how many of them are really obtaining long-term profits from using these applications? From a policy-makers’ point of view, we also believe that public support programs (technological infrastructure, training, consultancy) should be aimed at promoting the adoption and adequate implementation of social media generally in businesses and especially among exporting firms.

Limitations and future researchAlthough a great effort was made for obtaining a larger sample size of Spanish exporting companies, the final one used in this study is somewhat limited. We also cannot omit the risk of obtaining results that are overly specific to one particular context (in this case, Spain). In this vein, comparative studies drawing on larger multiple-country samples are crucial in internationalization research (Dhanaraj & Beamish, 2003). In addition, a larger sample of exporting firms would help to perform multi-group analysis comparing users and non-users of social media. This would also allow researchers to examine the specific role of the type of business sector in the adoption of social media more deeply, since it is likely that an IT outsourcing supplier or an online intermediary, for example, might have greater IT capability in general, as compared with an export-oriented manufacturer (Zhang et al., 2013).

Finally, although the TRA model and other adoption models have been studied and tested in cross-sectional studies (e.g., Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975); some authors have developed longitudinal test of the TRA and these studies suggest that, for relatively stable intentions, the TRA may have merit for longitudinal prediction of behavior. Likewise, other technology adoption models have been used to analyze individuals being introduced to a new technology in the workplace through a longitudinal study (e.g., Venkatesh et al., 2003). Due to the nature of our study and the difficulty of obtaining data, we have developed a cross-sectional study. However, we acknowledge that it could be interesting for future research to examine the stability of behavioral intentions within this domain, and to provide further longitudinal tests of the theory.

Furthermore, this research presents another limitation. Some common variables included in the original RBV and TRA model, have not been included in this research. For example, subjective norm included in the original TRA model is not considered. We decided not to include this variable since it has not been considered in more recent studies and, in a similar vein, we supposed that subjective norm is not an important variable to explain the behavior of managers regarding the use of Social Media in business strategy. However, as future research lines, we believe that other variables should be considered in order to analyze all the possible factors that could influence in the final use of Social Media.

FundingThis research was funded by the Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad, project ref. ECO2013-44027-P.