Although there is evidence that higher cognitive reserve (CR) is a protective factor and it has been related to better prognosis, there have been no studies to date that have explored the CR level and its impact in clinical, neurocognitive and lifestyle outcomes according to the stage of the disease: early stage of psychosis (ESP) or chronic schizophrenia (SCZ).

Material and methodsA total of 60 patients in the ESP and 225 patients with SCZ were enrolled in the study. To test the predictive capacity of CR for each diagnostic group, a logistic regression analysis was conducted. Hierarchical linear regression analyses were performed to explore the associations between CR and different outcomes. The mediation analyses were performed according to the principles of Baron and Kenny.

ResultsPatients with SCZ showed lower CR than those in the ESP (p<0.001). CR correctly classified 79.6% of the cases (p<0.001; Exp(B)=1.062). In ESP group, CR was related to working memory (p=0.030) and negative symptoms (p=0.027). CR (t=3.925, p<0.001) and cannabis use (t=2.023, p=0.048) explained 26.7% of the variance on functioning (p=0.003). In patients with SCZ, CR predicted all cognitive domains, negative symptoms (R2=0.091, p=0.001) and functioning (R2=0.074, p=0.005). In both ESP and SCZ groups, higher CR was associated with lower body mass index and circumference. In ESP group, the effect of adherence to Mediterranean diet on functioning (p=0.037) was mediated by CR level (p=0.003).

ConclusionsThe implications of CR depend on the stage of the disease (ESP vs. SCZ), with a greater effect on neurocognition and negative symptoms in patients with chronic SCZ.

In recent years, there has been a great deal of interest in the study of cognitive reserve (CR) in mental disorders.1 A higher CR level has been associated with later age of onset, lower negative symptoms’ severity, better neurocognitive performance and better psychosocial functioning in people with a first-episode of psychosis (FEP),2–6 schizophrenia (SCZ)7,8 and bipolar disorder.9–11 Thus, it has been suggested that CR may be a relevant factor in improving our understanding of the heterogeneity found in persons with severe mental illness.

CR is determined by genetic and environmental factors. Some environmental factors include potentially modifiable factors such as education, lifestyle and mental and physical activity.12 However, CR differs depending on pathology7 and it has been shown that in SCZ and related disorders the quantity of accumulated CR can be interfered by the disorder itself. In fact, a lower intelligence quotient (IQ), a component of CR, has been associated in children with increased vulnerability to develop a psychiatric disorder.13 When comparing CR level, it is higher in healthy controls than patients, and it has been shown that CR correctly classified the samples into patient or controls in ranges between 71.4 and 79.8%.2,14,15 Amongst patients, CR is higher in affective patients compared to non-affective.3 This fact may be due to cognitive deficits, lower premorbid IQ, education-occupation level and leisure activities that have been linked to SCZ.15 It has been shown that unhealthy behaviours, such as poor nutrition, and physical inactivity, could be related with lower CR16 and associated with worse cognitive performance.17

Although there is evidence that higher CR is a protective factor and it has been related to better prognosis, to date no studies have explored the CR level and its impact according to the stage of the disease: ESP or chronic SCZ. There is controversy in the literature about the stability of intelligence in SCZ. While in a study that compared current and premorbid IQ showed that approximately 70% of schizophrenia patients showed deterioration of IQ,18 another study did not find significant changes in IQ.19 With the chronicity of the disease, other aspects that are part of the CR concept, such as social, intellectual and leisure activities may also be affected. Identifying clinical, functional and neurocognitive phenotypes according to the estimated level of CR might provide relevant information that may allow us to define early personalized intervention and person-focused therapy.

This study aims at identifying potential unfolding differences of the psychotic illness by comparing the impact of CR on neurocognitive performance, psychosocial functioning and clinical outcomes in patients in the ESP and SCZ patients. We also analyzed whether a healthy lifestyle (diet factors and lifestyle habits), intestinal permeability and anthropometric measurements were associated with CR and whether CR moderates the effects of unhealthy lifestyle on clinical, functional and cognitive outcomes.

Material and methodsSampleThe sample of this study came from an observational, cross-sectional and multisite study including four centres in Spain (PI17/00246). Rationale, objective and protocol have been previously described.20 A total of 553 adult patients with DSM-5 schizophrenia spectrum disorder at any stage of the disease were included. For the current study we only included patients who had a score of Cognitive Reserve Assessment Scale in Health (CRASH) scale.14

The inclusion criteria were: (1) adults over 18 years of age; (2) ability to speak Spanish correctly and (3) signed informed consent. Exclusion criteria were: (1) history of head trauma with loss of consciousness and (2) organic disease with mental repercussions; (3) presence of an acute inflammatory process: (3.1) fever (>38°C) or infection in the two weeks prior to the baseline interview, or (3.2) have received vaccinations in the past 4 weeks.

Patients were divided into: (1) ESP group: those patients who had experienced their FEP over the previous 5 years; (2) patients with SCZ: those who had experienced their FEP more than 5 years ago and had a diagnosis of schizophrenia.

This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice and the Hospital Clinic Ethics and Research Board. All participants provided written informed consent prior to their inclusion in the study.

AssessmentSociodemographic assessmentIncluding age, gender, drug misuse habits, years of illness duration, first-degree relative with schizophrenia and diagnoses. Diagnostic was determined according to the diagnostic criteria of DSM-5 (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders) (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

Anthropometric assessmentAnthropometric measurements included weight, height, body mass index (BMI), body circumference and blood pressure.

Intestinal permeability, diet, and physical exercise assessmentLifestyle habits were assessed with the Mediterranean Diet Adherence Screener (MEDAS),21,22 and the Short Scale of Physical Activity (IPAQ).23 MEDAS is a validated questionnaire of Mediterranean diet adherence consisting of 14-items, used in the Prevención con Dieta Mediterránea (PREDIMED) study.24 MEDAS score was calculated by assigning a score of 1 and 0 for each item.

IPAQ “activity” assesses specific types of activity such as walking, moderate-intensity activities and vigorous intensity activities. Frequency (measured in days per week) and duration (time per day) are collected separately for each specific type of activity. IPAQ “sitting” (sedentary), assesses time spent sitting. Continuous score IPAQ results are expressed as MET-min per week and calculated by multiplying the MET assigned to it (vigorous – 8 MET, moderate – 4 MET and walking – 3.3 MET) by the number of days it was performed during a week, where MET corresponds to O2 consumption during the rest and equals 3.5mL O2/kg of the body mass per minute. Finally, intestinal permeability was assessed using the permeable-intestine-syndrome questionnaire, consisting of 19 items, using 4-point Likert scale ranging from 0 “never” to 3 “everyday”.

Clinical and functional assessmentA psychopathological assessment was carried out with the Spanish version of the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS)25 and the Clinical Global Impression Scale (CGI-S).26 Higher scores indicate greater severity.

The functioning level was assessed by Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF).27 It is a scale used to assess the severity of symptoms and the level of functioning, on a numeric scale from 1 to 100. Higher scores indicate better functioning.

Neuropsychological assessmentTo assess cognitive impairment the Spanish version of the Screen for Cognitive Impairment in Psychiatry (SCIP-S) has been administered.28 It has five subtests for evaluating immediate (VLT-I) and delayed verbal learning (VLT-D), working memory (WMT), verbal fluency (VFT), and processing speed (PST). The range score goes from 0 to 30 in VLT-I, 0–24 in WMT, ≥0 in VFT, 0–10 in VLT-D and 0–30 in PST. A total score is calculated from the sum of the subscale scores. In all neurocognitive domains higher scores correspond to better performance.

Cognitive reserve assessmentTo assess CR, the Cognitive Reserve Assessment Scale in Health (CRASH) was used. It has showed optimal psychometric properties and it has been demonstrated to be a valid tool to assess CR.14 The scale's maximum total score is 90. Higher score in this scale indicates greater CR.

Statistical analysisDescriptive analyses were conducted using Student's t-test for continuous variables and chi-square for categorical variables. To test the predictive capacity of CRASH for each diagnostic group, a logistic regression analysis was conducted. Pearson bivariate correlations were performed to identify continuous variables significantly correlated with cognitive reserve (measured by CRASH) and Student's t-test for categorical variables.

Hierarchical linear regression analyses were performed to explore the associations between CR and neurocognitive performance, negative symptoms and functioning. The five neurocognitive subtests, PANSS negative and GAF scores were introduced as the dependent variables in each model. We introduced independent variables based on data obtained in previous studies, including current age, cannabis use, and sex.

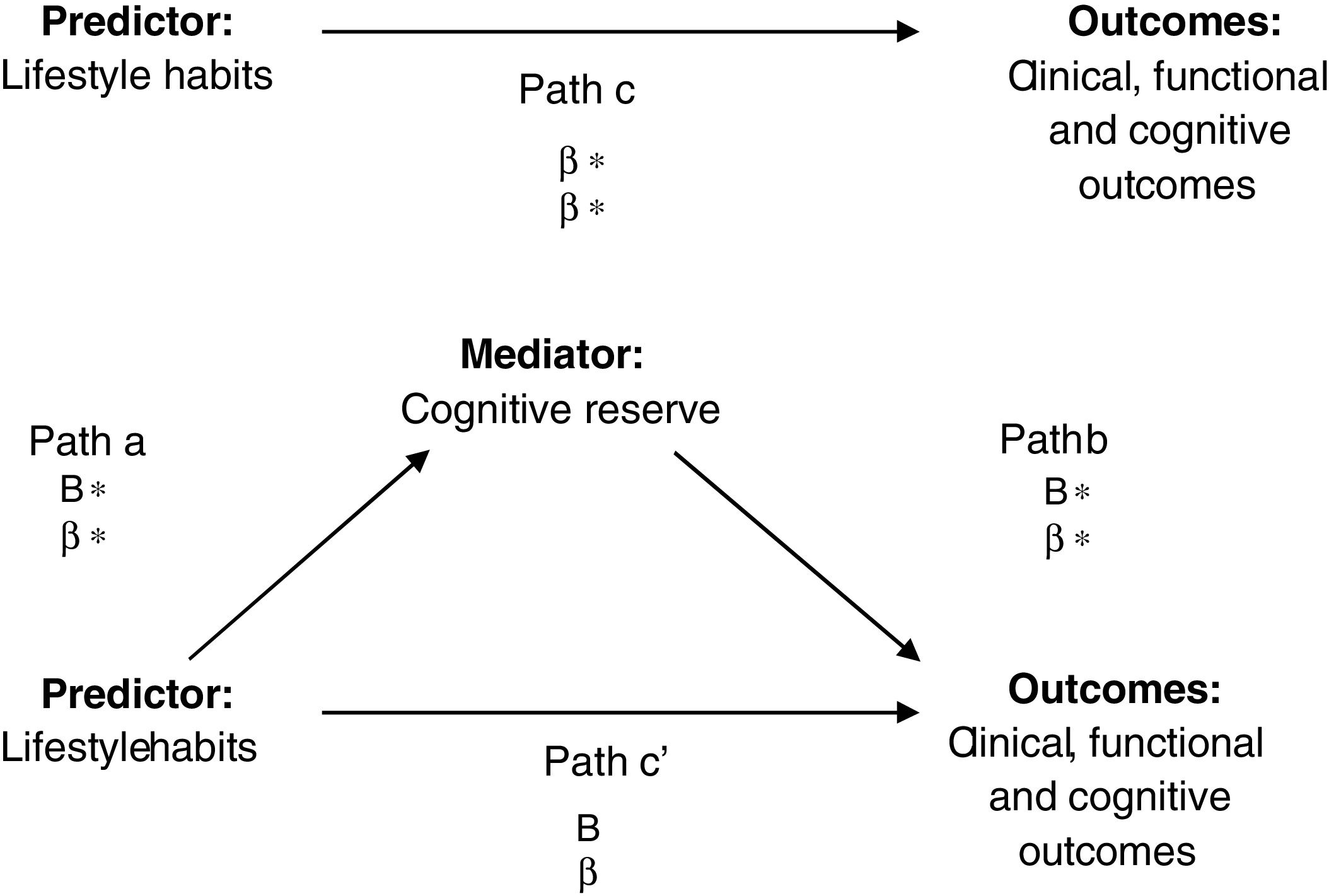

The mediation analyses were performed according to the principles of Baron and Kenny.29 In the first instance, the independent variable (lifestyle) was significantly related to the dependent variable (clinical, functional and cognitive outcomes) (path c). In the second equation, the independent variable (lifestyle) was significantly related to the proposed mediator (cognitive reserve) (path a). Finally, in the third equation, the dependent (clinical, functional and cognitive outcomes) was regressed onto the independent variable (lifestyle), adjusted for the mediator (cognitive reserve) (see Fig. 1). Hence, if the independent variable is no longer significant when the mediator is controlled, the finding supports full mediation. If the independent variable is still significant, the finding supports partial mediation.

Path analyses: effect of subject on cognitive domains or clinical symptoms mediated by cognitive reserve. B=unstandardized values; β=standardized values. *p<0.05. Mediation was identified if the following criteria were met: (1) the independent variable was significantly related to the dependent variable (path c); (2) the independent variable was significantly related to the proposed mediator (path a); (3) the proposed mediator was significantly related to the dependent variable when controlling for the effects of the independent variable (path b); (4) the independent variable was not significantly related to the dependent variable when controlling for the effects of the proposed mediator (path c’).

Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS v26) was used to analyze data. All statistical tests were carried out two-tailed, with an alpha level of significance set at p<0.05.

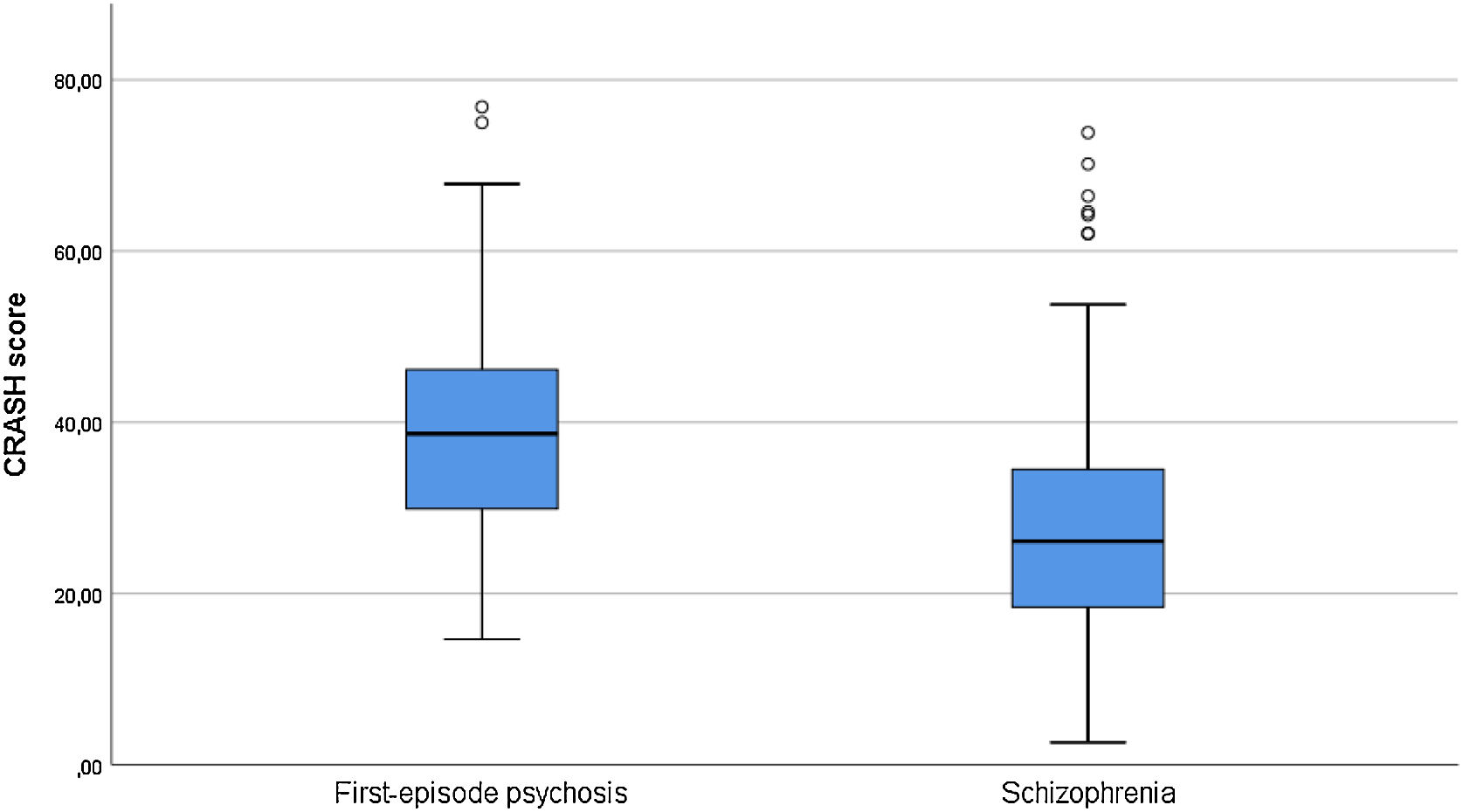

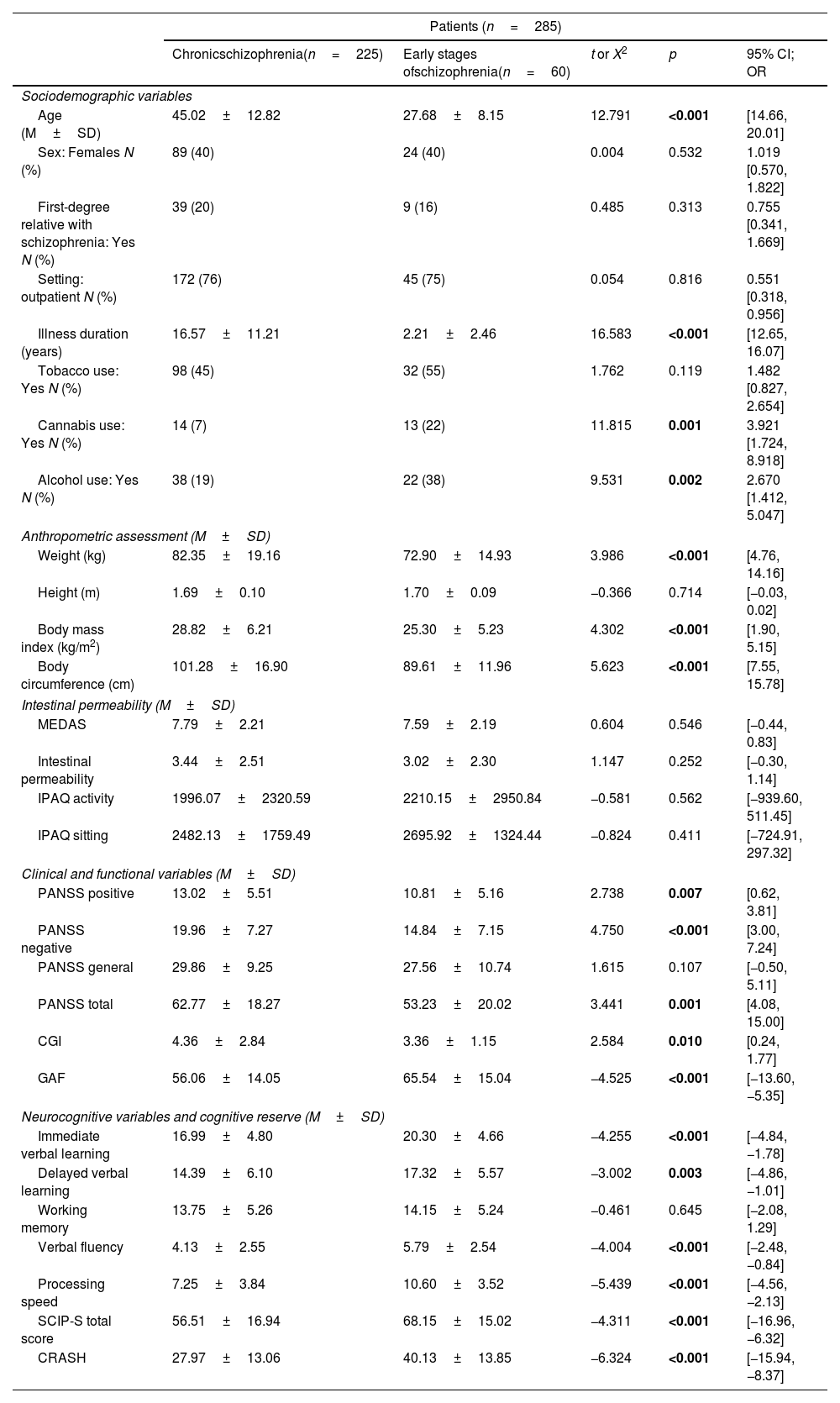

ResultsDifferences in sociodemographic, clinical, functional and neurocognitive characteristics for schizophrenia and first-episode psychosis patientsA total of 60 patients in the ESP and 225 patients with chronic SCZ were enrolled in the study. A summary of the sociodemographic and clinical characteristics is shown in Table 1. There were no differences between ESP and SCZ groups in terms of gender, having a first-degree relative with SCZ, treatment setting (outpatient/inpatient), tobacco use and working memory performance. Patients with SCZ were older (p<0.001), with lower cannabis and alcohol use (p=0.001 and p=0.002, respectively), higher positive (p=0.007) and negative (p<0.001) psychotic symptoms, higher severity of illness (p=0.010) and worse functioning (p<0.001). They also presented higher BMI (p<0.001) and body circumference (p<0.001). Regarding neurocognitive performance, SCZ patients performed worse than patients in the ESP in verbal memory (immediate and delayed, p<0.001 and p=0.003), verbal fluency (p<0.001), processing speed (p<0.001) and global cognitive performance (total SCIP-S) (p<0.001). Patients with SCZ also showed lower CRASH scores than patients in the ESP (p<0.001) (see Fig. 2). In fact, lower CRASH was also associated with longer illness duration (r=−0.335, p<0.001). Although higher age was associated with lower cognitive reserve (r=−0.269, p<0.001), these differences remain significant after adjustment for age (p<0.001). After performing a logistic regression to assess the predictive power of CRASH for each group (ESP/SCZ), the model explained between 11.2% (Cox & Snell R Square) and 17.5% (Nagelkerke R Square) of the variance and correctly classified 79.6% of the cases (B=0.061; p<0.001; Exp(B)=1.062).

Differences in sociodemographic, clinical, functional and neurocognitive characteristics for chronic schizophrenia and early stages of schizophrenia.

| Patients (n=285) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chronicschizophrenia(n=225) | Early stages ofschizophrenia(n=60) | t or X2 | p | 95% CI; OR | |

| Sociodemographic variables | |||||

| Age (M±SD) | 45.02±12.82 | 27.68±8.15 | 12.791 | <0.001 | [14.66, 20.01] |

| Sex: Females N (%) | 89 (40) | 24 (40) | 0.004 | 0.532 | 1.019 [0.570, 1.822] |

| First-degree relative with schizophrenia: Yes N (%) | 39 (20) | 9 (16) | 0.485 | 0.313 | 0.755 [0.341, 1.669] |

| Setting: outpatient N (%) | 172 (76) | 45 (75) | 0.054 | 0.816 | 0.551 [0.318, 0.956] |

| Illness duration (years) | 16.57±11.21 | 2.21±2.46 | 16.583 | <0.001 | [12.65, 16.07] |

| Tobacco use: Yes N (%) | 98 (45) | 32 (55) | 1.762 | 0.119 | 1.482 [0.827, 2.654] |

| Cannabis use: Yes N (%) | 14 (7) | 13 (22) | 11.815 | 0.001 | 3.921 [1.724, 8.918] |

| Alcohol use: Yes N (%) | 38 (19) | 22 (38) | 9.531 | 0.002 | 2.670 [1.412, 5.047] |

| Anthropometric assessment (M±SD) | |||||

| Weight (kg) | 82.35±19.16 | 72.90±14.93 | 3.986 | <0.001 | [4.76, 14.16] |

| Height (m) | 1.69±0.10 | 1.70±0.09 | −0.366 | 0.714 | [−0.03, 0.02] |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 28.82±6.21 | 25.30±5.23 | 4.302 | <0.001 | [1.90, 5.15] |

| Body circumference (cm) | 101.28±16.90 | 89.61±11.96 | 5.623 | <0.001 | [7.55, 15.78] |

| Intestinal permeability (M±SD) | |||||

| MEDAS | 7.79±2.21 | 7.59±2.19 | 0.604 | 0.546 | [−0.44, 0.83] |

| Intestinal permeability | 3.44±2.51 | 3.02±2.30 | 1.147 | 0.252 | [−0.30, 1.14] |

| IPAQ activity | 1996.07±2320.59 | 2210.15±2950.84 | −0.581 | 0.562 | [−939.60, 511.45] |

| IPAQ sitting | 2482.13±1759.49 | 2695.92±1324.44 | −0.824 | 0.411 | [−724.91, 297.32] |

| Clinical and functional variables (M±SD) | |||||

| PANSS positive | 13.02±5.51 | 10.81±5.16 | 2.738 | 0.007 | [0.62, 3.81] |

| PANSS negative | 19.96±7.27 | 14.84±7.15 | 4.750 | <0.001 | [3.00, 7.24] |

| PANSS general | 29.86±9.25 | 27.56±10.74 | 1.615 | 0.107 | [−0.50, 5.11] |

| PANSS total | 62.77±18.27 | 53.23±20.02 | 3.441 | 0.001 | [4.08, 15.00] |

| CGI | 4.36±2.84 | 3.36±1.15 | 2.584 | 0.010 | [0.24, 1.77] |

| GAF | 56.06±14.05 | 65.54±15.04 | −4.525 | <0.001 | [−13.60, −5.35] |

| Neurocognitive variables and cognitive reserve (M±SD) | |||||

| Immediate verbal learning | 16.99±4.80 | 20.30±4.66 | −4.255 | <0.001 | [−4.84, −1.78] |

| Delayed verbal learning | 14.39±6.10 | 17.32±5.57 | −3.002 | 0.003 | [−4.86, −1.01] |

| Working memory | 13.75±5.26 | 14.15±5.24 | −0.461 | 0.645 | [−2.08, 1.29] |

| Verbal fluency | 4.13±2.55 | 5.79±2.54 | −4.004 | <0.001 | [−2.48, −0.84] |

| Processing speed | 7.25±3.84 | 10.60±3.52 | −5.439 | <0.001 | [−4.56, −2.13] |

| SCIP-S total score | 56.51±16.94 | 68.15±15.02 | −4.311 | <0.001 | [−16.96, −6.32] |

| CRASH | 27.97±13.06 | 40.13±13.85 | −6.324 | <0.001 | [−15.94, −8.37] |

CGI: Clinical Global Impression Scale; CRASH: Cognitive Reserve Assessment Scale in Health; GAF: Global Assessment of Functioning; IPAQ: Short Scale of Physical Activity; M: mean; MEDAS: Mediterranean Diet Adherence Screener; PANSS: Positive and Negative Symptom Scale. Significant differences (p<0.05) marked in bold.

There were no differences between those patients who reported cannabis use and those who did not in terms of CR (t=−1.626, p=0.105) or neurocognitive performance (immediate verbal learning, t=−0.213, p=0.832; delayed verbal learning, t=0.543, p=0.588; working memory, t=−0.139, p=0.889; verbal fluency, t=−0.550, p=0.583; processing speed, t=−1.188, p=0.236). There were also no differences when patients in the ESP and SCZ were analyzed separately.

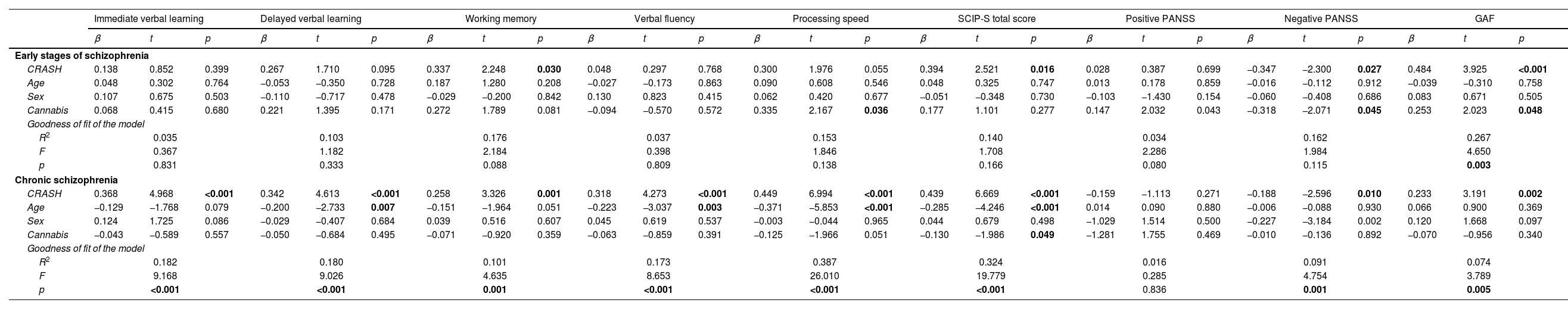

Predictive capacity of cognitive reserve on neurocognitive, clinical and functional outcomes according to the stage of the disease (ESP vs. schizophrenia)In patients in the ESP, CR did not predict any neurocognitive domain. Nevertheless, a correlation was observed between higher CR and working memory (t=2.248, p=0.030). CR (t=3.925, p<0.001) and cannabis use (t=2.023, p=0.048) explained 26.7% of the variance on functioning (F=4.650, p=0.003). Although CR was related with negative psychotic symptoms (t=−2.300, p=0.027), the model was not significant (p=0.115).

In patients with SCZ, CR explained 18.2% of the variance on immediate verbal learning (p<0.001) and 10.1% of working memory (p=0.001). Higher CR and lower age were significant predictors of delayed verbal learning performance (R2=0.180, F=9.026, p<0.001), verbal fluency (R2=0.173, F=8.653, p<0.001) and processing speed (R2=0.387, F=26.010, p<0.001). Higher CR, lower age and lower cannabis use predicted SCIP-S total score (R2=0.324, F=19.779, p<0.001). Finally, higher CR predicted lower negative psychotic symptoms severity (R2=0.091, F=4.754, p=0.001) and better functioning (R2=0.074, F=3.789, p=0.005). A summary of the predictive capacity of cognitive reserve is shown in Table 2.

Predictive capacity of cognitive reserve on neurocognitive, clinical and functional outcomes according to the stage of the disease (early stages of schizophrenia vs. chronic schizophrenia).

| Immediate verbal learning | Delayed verbal learning | Working memory | Verbal fluency | Processing speed | SCIP-S total score | Positive PANSS | Negative PANSS | GAF | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | t | p | β | t | p | β | t | p | β | t | p | β | t | p | β | t | p | β | t | p | β | t | p | β | t | p | |

| Early stages of schizophrenia | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| CRASH | 0.138 | 0.852 | 0.399 | 0.267 | 1.710 | 0.095 | 0.337 | 2.248 | 0.030 | 0.048 | 0.297 | 0.768 | 0.300 | 1.976 | 0.055 | 0.394 | 2.521 | 0.016 | 0.028 | 0.387 | 0.699 | −0.347 | −2.300 | 0.027 | 0.484 | 3.925 | <0.001 |

| Age | 0.048 | 0.302 | 0.764 | −0.053 | −0.350 | 0.728 | 0.187 | 1.280 | 0.208 | −0.027 | −0.173 | 0.863 | 0.090 | 0.608 | 0.546 | 0.048 | 0.325 | 0.747 | 0.013 | 0.178 | 0.859 | −0.016 | −0.112 | 0.912 | −0.039 | −0.310 | 0.758 |

| Sex | 0.107 | 0.675 | 0.503 | −0.110 | −0.717 | 0.478 | −0.029 | −0.200 | 0.842 | 0.130 | 0.823 | 0.415 | 0.062 | 0.420 | 0.677 | −0.051 | −0.348 | 0.730 | −0.103 | −1.430 | 0.154 | −0.060 | −0.408 | 0.686 | 0.083 | 0.671 | 0.505 |

| Cannabis | 0.068 | 0.415 | 0.680 | 0.221 | 1.395 | 0.171 | 0.272 | 1.789 | 0.081 | −0.094 | −0.570 | 0.572 | 0.335 | 2.167 | 0.036 | 0.177 | 1.101 | 0.277 | 0.147 | 2.032 | 0.043 | −0.318 | −2.071 | 0.045 | 0.253 | 2.023 | 0.048 |

| Goodness of fit of the model | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| R2 | 0.035 | 0.103 | 0.176 | 0.037 | 0.153 | 0.140 | 0.034 | 0.162 | 0.267 | ||||||||||||||||||

| F | 0.367 | 1.182 | 2.184 | 0.398 | 1.846 | 1.708 | 2.286 | 1.984 | 4.650 | ||||||||||||||||||

| p | 0.831 | 0.333 | 0.088 | 0.809 | 0.138 | 0.166 | 0.080 | 0.115 | 0.003 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Chronic schizophrenia | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| CRASH | 0.368 | 4.968 | <0.001 | 0.342 | 4.613 | <0.001 | 0.258 | 3.326 | 0.001 | 0.318 | 4.273 | <0.001 | 0.449 | 6.994 | <0.001 | 0.439 | 6.669 | <0.001 | −0.159 | −1.113 | 0.271 | −0.188 | −2.596 | 0.010 | 0.233 | 3.191 | 0.002 |

| Age | −0.129 | −1.768 | 0.079 | −0.200 | −2.733 | 0.007 | −0.151 | −1.964 | 0.051 | −0.223 | −3.037 | 0.003 | −0.371 | −5.853 | <0.001 | −0.285 | −4.246 | <0.001 | 0.014 | 0.090 | 0.880 | −0.006 | −0.088 | 0.930 | 0.066 | 0.900 | 0.369 |

| Sex | 0.124 | 1.725 | 0.086 | −0.029 | −0.407 | 0.684 | 0.039 | 0.516 | 0.607 | 0.045 | 0.619 | 0.537 | −0.003 | −0.044 | 0.965 | 0.044 | 0.679 | 0.498 | −1.029 | 1.514 | 0.500 | −0.227 | −3.184 | 0.002 | 0.120 | 1.668 | 0.097 |

| Cannabis | −0.043 | −0.589 | 0.557 | −0.050 | −0.684 | 0.495 | −0.071 | −0.920 | 0.359 | −0.063 | −0.859 | 0.391 | −0.125 | −1.966 | 0.051 | −0.130 | −1.986 | 0.049 | −1.281 | 1.755 | 0.469 | −0.010 | −0.136 | 0.892 | −0.070 | −0.956 | 0.340 |

| Goodness of fit of the model | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| R2 | 0.182 | 0.180 | 0.101 | 0.173 | 0.387 | 0.324 | 0.016 | 0.091 | 0.074 | ||||||||||||||||||

| F | 9.168 | 9.026 | 4.635 | 8.653 | 26.010 | 19.779 | 0.285 | 4.754 | 3.789 | ||||||||||||||||||

| p | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.836 | 0.001 | 0.005 | ||||||||||||||||||

Results considered significant at p<0.05 and marked bold. CRASH: Cognitive Reserve Assessment Scale in Health; GAF: Global Assessment of Functioning; PANSS: Positive and Negative Symptom Scale; SCIP: Spanish version of the Screen for Cognitive Impairment in Psychiatry.

All results are maintained after controlling for clozapine use.

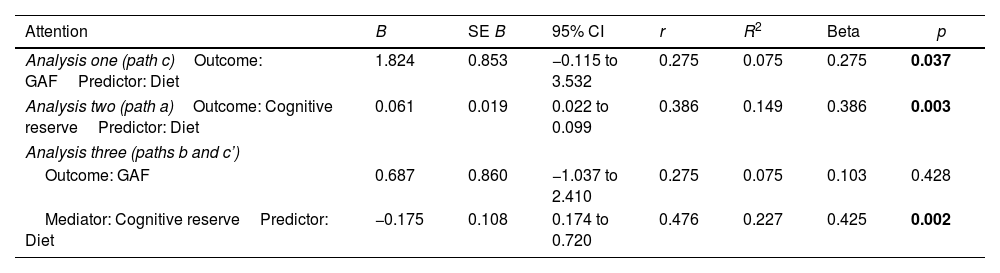

Cognitive reserve, lifestyle habits and anthropometric measurementsAs already mentioned, SCZ and patients in the ESP did not show differences in healthy lifestyle, however SCZ patients had higher BMI (p<0.001) and body circumference (p<0.001). In patients in the ESP, higher CR was associated with higher adherence to Mediterranean diet (r=0.386, p=0.003), lower weight (r=−0.289, p=0.029), lower BMI (r=−0.267, p=0.046), and lower body circumference (r=−0.407, p=0.003) (see Supplementary Table 1). Regarding the mediation analysis, intestinal permeability and physical activity were not related to CR, and thus mediation analysis could not be carried out. The effect of adherence to Mediterranean diet on functioning (p=0.037) was mediated by CR level (p=0.003) (see Table 3). That is, the independent variable (diet) was no longer significant (p=0.428) when the mediator (CR) (p=0.002) was controlled.

Testing mediator effects using linear regression analyses in FEP patients.

| Attention | B | SE B | 95% CI | r | R2 | Beta | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Analysis one (path c)Outcome: GAFPredictor: Diet | 1.824 | 0.853 | −0.115 to 3.532 | 0.275 | 0.075 | 0.275 | 0.037 |

| Analysis two (path a)Outcome: Cognitive reservePredictor: Diet | 0.061 | 0.019 | 0.022 to 0.099 | 0.386 | 0.149 | 0.386 | 0.003 |

| Analysis three (paths b and c’) | |||||||

| Outcome: GAF | 0.687 | 0.860 | −1.037 to 2.410 | 0.275 | 0.075 | 0.103 | 0.428 |

| Mediator: Cognitive reservePredictor: Diet | −0.175 | 0.108 | 0.174 to 0.720 | 0.476 | 0.227 | 0.425 | 0.002 |

Significant differences (p<0.05) marked in bold. Note that only the mediating variables that are statistically significant with the predictor are shown. GAF: Global Assessment of Functioning.

In patients with SCZ, higher CR was associated with lower BMI (r=−0.156, p=0.023), and lower body circumference (r=−0.141, p=0.048). No relationship has been found between CR levels and substance use. Intestinal permeability and physical activity were related to functioning but CR was not related to them, and thus mediation analysis could not be carried out.

DiscussionThe most important finding of the study is that the patients in the ESP showed higher CR than patients with SCZ, so that CR depends on the stage of the disease.

Patients in the ESP were younger, with higher cannabis and alcohol use, lower psychotic symptoms’ severity and better functioning. Previous literature, but not our study, has shown that patients in the ESP presented more positive symptoms but fewer negative symptoms.30 It is possible that the patients who entered in the study were more stable as most were recruited in outpatient setting. Moreover, not having found differences in negative symptoms may be due to the fact that primary negative symptoms are inherent to the disease process itself and they tend to be stable and persistent.31 Compared with patients in the ESP, chronic SCZ patients performed worse in all cognitive domains except for working memory, suggesting that these impairments might result from the burden of disease, associated with the chronicity of the illness. A recent review suggests that longitudinal studies with more than 10 years of follow-up support mild cognitive declines after psychosis onset until late adulthood.32 Our results are also in accordance with previous studies in which the working memory was not significantly different between patients in the ESP and chronic SCZ, suggesting stability of the deficits over time.33

Regarding CR, it was higher in patients in the ESP. We found that the CRASH scale correctly classified the sample into ESP or chronic SCZ (79.6%). The onset of psychosis supposes an interruption in life development at early stages that is closely related to the later functional outcomes. Our results suggest that some determinants of CR such as intellectual and leisure activities (physical, intellectual, artistic, and cultural) including sociability and withdrawal (type and quantity of relationships) may be more impaired in chronic patients.

In accordance with previous literature, we found that patients in the ESP who have a high CR presented fewer negative symptoms, greater functioning and better working memory performance.2,15 However, other neurocognitive domains such as verbal memory have not been associated with CR. This may be due to the fact that the neuropsychological assessment was performed using a screening scale, whereas in the other articles a neuropsychological battery was used. Other cognitive domains that have been found to be associated with CR, such as attention and executive functioning, were not collected in the present study. In patients with SCZ, CR predicted all cognitive domains, negative symptoms and functioning. Taking into account that patients in the ESP had lower structural and functional alterations than chronic SCZ patients,34 and that CR refers to the brain's capacity to face a pathology using alternative, or more efficient, cerebral networks in order to minimize symptoms,35 the effect is therefore expected to be greater in patients with SCZ.

Finally, in terms of healthy lifestyle and anthropometric measurements, patients with SCZ presented higher BMI and body circumference. However, they did not show differences in healthy lifestyle factors (diet, physical activity) or reported intestinal permeability. In both ESP and chronic SCZ groups, higher CR was associated with lower BMI. CR is associated with negative psychotic symptoms,2,3 and it has been demonstrated that lower negative symptoms were associated with higher BMI.36 Thus, it seems that there is a complex relationship between CR, negative symptoms and BMI. In patients in the ESP, higher CR was also associated with higher adherence to Mediterranean diet, and the mediation analysis revealed that the effect of adherence to diet on functioning was mediated by the CR level. Crichton et al. found that in an Australian sample of middle-aged Mediterranean diet was not related to cognitive function, but was positively associated with physical function and general health, and negatively associated with trait anxiety, depression and perceived stress.37 Our result suggests that CR should be taken into account to explore this relationship more accurately.

Notwithstanding, some limitations should be considered. Firstly, to assess cognitive impairment, the Screen for Cognitive Impairment in Psychiatry (SCIP-S) has been administered. To evaluate patients in the ESP, a comprehensive neuropsychological test could be more useful determining the severity of a person's cognitive difficulties and their functional limitations. In addition, the SCIP-S does not include key domains such as executive functions or attention. Secondly, although GAF is one of the of the most widely used scale in clinical and research practice, it seems to reflect symptom severity whereas other scales such as the Functional Assessment Short Test (FAST)38 are designed to assess the main functioning problems experienced by psychiatric patients39 and might better reflect the difficulties in daily functioning (autonomy, occupational functioning, cognitive functioning, financial issues, interpersonal relationships, and leisure time). Thirdly, in this study the diagnosis of the FEP group was not recorded. Fourthly, it is not a longitudinal study. However, this is a naturalistic and multicenter study which includes a large sample of patients with high heterogeneity corresponding to the usually treated population, in which variables of high interest have been collected for the study of intestinal endothelial permeability as a cause of chronic low-grade inflammation in patients with SCZ, and its relationship with diet, metabolic syndrome, disease severity and functionality.

In conclusion, the implications of CR depend on the stage of the disease, with a greater effect on neurocognition and negative symptoms in patients with SCZ. The results obtained suggest that CR can be used as a reliable indicator for the prognosis.

Authors’ contributionsBA and GS designed the project. BA, GS, MB, and MPGP coordinated the project development. SA and GA drafted the manuscript. SA, GA, GS, MA, CH, MSA, FPB, LGB, MPGP, and BA participated in the recruitment. SA performed the statistical analyses. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

FundingThis study was supported by a grant from the Instituto de Salud Carlos III-Fondos Europeos de Desarrollo Regional (FEDER) (grant number PI17/00246) and by the programme “Ajuts per donar suport a l’activitat científica dels grups de recerca de Catalunya (SGR-Cat 2021)”, Agència de Gestió d’Ajuts Universitaris i de Recerca (AGAUR) (grant 2021 SGR 01380).

Conflicts of interestGerard Anmella has received CME-related honoraria, or consulting fees from Janssen-Cilag, Lundbeck, Lundbeck/Otsuka, and Angelini, with no financial or other relationship relevant to the subject of this article.

Silvia Amoretti has been a consultant to and/or has received honoraria/grants from Otsuka-Lundbeck, with no financial or other relationship relevant to the subject of this article.

Maria Paz Garcia-Portilla has been a consultant to and/or has received honoraria/grants from Adamed, Angelini, Casen Recordati, Alianza Otsuka-Lundbeck, Janssen-Cilag, Lundbeck, Otsuka, and SAGE Therapeutics.

Leticia Gonzalez-Blanco has received honoraria for lecturing, research and/or travel grants for attending conferences from the Spanish Foundation of Psychiatry and Mental Health, Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Otsuka-Lundbeck, Janssen-Cilag, Angelini, Casen Recordati and Pfizer.

Miquel Bernardo has been a consultant for, received grant/research support and honoraria from, and been on the speakers/advisory board of ABBiotics, Adamed, Angelini, Casen Recordati, Janssen-Cilag, Menarini, Rovi and Takeda.

Belen Arranz has been a consultant/has received honoraria or grants from Adamed, Janssen-Cilag, Lundbeck, Otsuka and Takeda, with no conflict of interest related to this manuscript.

All other authors report no financial or other relationship relevant to the subject of this article.

We are extremely grateful to all participants.

We would also like to thank the Carlos III Healthcare Institute, the Spanish Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities, the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF/FEDER) (PI17/00246), CIBERSAM; and the Government of the Principality of Asturias PCTI-2021-2023 IDI/2021/111.

Silvia Amoretti has been supported by Sara Borrell doctoral programme (CD20/00177) and M-AES mobility fellowship (MV22/00002), from the Instituto de Salud Carlos III (ISCIII), and co-funded by European Social Fund “Investing in your future”. This work was supported by La Marató-TV3 Foundation grants 202234-32 (to SA) and 202205-10 (to MB).

Gerard Anmella is supported by a Rio Hortega 2021 grant (CM21/00017) and M-AES mobility fellowship (MV22/00058), from the Spanish Ministry of Health financed by the Instituto de Salud Carlos III (ISCIII) and co-financed by the Fondo Social Europeo Plus (FSE+).

Miquel Bernardo thanks the support of the Spanish Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities (PI08/0208; PI11/00325; PI14/00612) integrated into the Plan Nacional de I+D+I y cofinanciado por el ISCIII-Subdirección General de Evaluación y el Fondo Eurpeo del Desarrollo Regional (FEDER). Unión Europea. Una manera de hacer Europa, Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red de salud Mental, CIBERSAM, by the CERCA Programme/Generalitat de Catalunya AND Secretaria d’Universitats i Recerca del Departament d’Economia I Coneixement (2017SGR1355). Departament de Salut de la Generalitat de Catalunya, en la convocatoria corresponent a l’any 2017 de concessió de subvencions del Pla Estratègic de Recerca i Innovació en Salut (PERIS) 2016-2020, modalitat Projectes de recerca orientats a l’atenció primària, amb el codi d’expedient SLT006/17/00345. MB is also grateful for the support of the Institut de Neurociències, Universitat de Barcelona.