Social cognition (SC) and executive function (EF) have been described as important variables for social functioning and recovery of patients with psychosis. However, the relationship between SC and EF in first-episode psychosis (FEP) deserves further investigation, especially focusing on gender differences.

AimsTo investigate the relationship between EF and different domains of SC in FEP patients and to explore gender differences in the relationship between these domains.

MethodsA cross-sectional study of 191 patients with new-onset psychosis recruited from two multicenter clinical trials. A comprehensive cognitive battery was used to assess SC (Hinting Task, Face Test and IPSAQ) and EF (TMT, WSCT, Stroop Test and digit span – WAIS-III). Pearson correlations and linear regression models were performed.

ResultsA correlation between Theory of Mind (ToM), Emotional Recognition (ER) and EF was found using the complete sample. Separating the sample by gender showed different association profiles between these variables in women and men.

ConclusionsA relationship between different domains of SC and EF is found. Moreover, women and men presented distinct association profiles between EF and SC. These results should be considered in order to improve the treatment of FEP patients and designing personalized interventions by gender.

Social cognition (SC) is defined as a set of neurocognitive processes related to the understanding, recognizing, processing, and appropriate use of social stimuli in one's environment. Moreover, SC is also considered to be the collection of mental processes underlying people's capacity to perceive, process and comprehend social information.1 SC includes different subdomains, such as Theory of Mind (ToM), Emotional Recognition (ER) and attributional style, most of which have been found to be impaired in people with psychosis.2,3

ToM refers to the cognitive ability to represent one's and others’ mental states, in terms of thinking, believing, or pretending.4 Most studies report that people with FEP perform worse than healthy controls in ToM tasks.5

ER is the ability to interpret the emotions of others based on facial expressions.6 Several studies have found pronounced problems in ER in established schizophrenia, especially with negative emotions.7 These deficits are already present in people at clinical high-risk and in the early stages of psychosis.8,9

Attributional style refers to how individuals explain the causes of events, and it has been shown that individuals who tend to explain negative events as due to external causes seem more prone to develop delusional beliefs.10 Several studies suggest that attributional biases may be an important feature of psychosis.11,12 Often, studies have described two attributional biases: an externalizing bias (outsourcing blame for negative events) and a personalizing bias (blaming others for the negative events). In general, patients with psychosis are slightly more prone to showing a self-serving attributional style, especially when in a state of active persecutory delusions or paranoia.13

Executive function and psychotic disordersExecutive function (EF) is a general construct that encompasses the high-level cognitive processes that enable individuals to regulate their thoughts and actions during goal-directed behavior.14 These processes include working memory, verbal fluency, flexibility, inhibitory control and problem solving.

Among the well-demonstrated impairments in neurocognitive domains in both FEP and established psychosis,15 a large body of evidence suggests that executive dysfunction is a core feature of schizophrenia, as it is the most commonly altered cognitive domain in psychosis,16 and this impairment is already apparent at the FEP stage.17

Social cognition and executive functionAlthough the processing of socially relevant information requires neurocognitive capacities (memory, attention and EF), a review by Mehta et al.18 showed that SC and neurocognition are largely independent domains. Some studies have suggested a possible association between neurocognitive performance and SC in FEP,19 as people with FEP show cognitive deficits and impaired SC that interfere with the course of the disease.2,20

However, previous research results have been inconsistent. While some studies suggest that ToM impairments are associated with poorer general neurocognition21 and working memory,22 other studies have not found this association with EF.23,24 Regarding ER, data suggest that there may be a relationship between EF and ER.18 As for other social cognitive subdomains, personalizing bias for negative events appears to be associated with perseverative errors on the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test; and inhibitory control has been associated with internal attributions for negative events in patients with paranoid schizophrenia.25

However, both EF and SC have been described in psychosis as variables that are important for patients’ social functioning and recovery,26 and therefore, it seems that further understanding of their potential associations may be beneficial to developing better treatment so as to prevent functional decline.

GenderA number of studies have examined gender differences in psychosis. Evidence is still inconsistent regarding neurocognition, as some studies have found gender differences in performance,27 while others have found no differences between men and women.28

Similarly, results in SC are still inconclusive, as most studies have failed to find gender differences,29,30 while others have reported a trend to significance in emotional processing31 and better ToM in women.32 Additionally, clusters of patients based on SC with FEP describe different profiles in men and women.33

To the best of our knowledge there are only two studies that have investigated SC, neurocognition and its relationship with gender,29,34 although neither of them focused specifically on EF.

Thus, this study's hypothesis is that a relationship between EF and SC will be found, particularly in ToM and ER. Additionally, the effect of gender on this relationship will be explored, hypothesizing that different variables of EF will explain differences in SC domains between men and women.

Aim of the study.This study aimed to:

- I.

Explore the relationship between EF and different domains of SC in FEP patients.

- II.

Explore gender differences in the relationship between these domains.

We performed a cross-sectional study based on data from two multicenter clinical trials (PI11/01347 and PI14/00044). More details on the design of the original study are described in the source article.35

SampleThe sample was composed of outpatients with recent-onset psychosis treated at one of these participating mental health centers: Servicio Andaluz de Jaén, Málaga and Motril (Granada), Salut Mental Parc Taulí (Sabadell), Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau (Barcelona), Parc Salut Mar (Barcelona), Centro de Higiene Mental de les Corts (Barcelona), Institut d’Assistència Sanitària Girona, Institut Pere Mata (Reus), Fundación Jímenez Díaz (Madrid), Hospital Clínico Universitario de Valencia and Parc Sanitari Sant Joan de Déu (Coordinating center). A total of 191 patients were included in this study.

Inclusion criteria were: (1) a diagnosis of schizophrenia, psychotic disorder not otherwise specified, delusional disorder, schizoaffective disorder, brief psychotic disorder, or schizophreniform disorder (according to DSM-IV-TR); (2) <5 years from the onset of symptoms; (3) a score ≥3 in delusions, grandiosity or suspicions on the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) during the previous year; and (4) age between 16 and 45 years. Exclusion criteria were: (1) traumatic brain injury, dementia, or intellectual disability (premorbid IQ ≤70); (2) substance dependence according to DSM-IV-TR criteria; and (3) PANSS ≥5 in hostility and uncooperativeness and ≥6 in suspiciousness.

AssessmentsAll patients received a complete sociodemographic, clinical, neuropsychological and social cognitive assessment. Assessments were carried out on two different days.

Assessment of social cognition included:

- -

The Hinting Task was used to assess ToM.36,37 This task uses short stories with two characters. After each story, participants interpret the meaning behind a character's hint. In the current study two samples were used: a subset of the sample was assessed with three or six stories. A composite measure has been used dividing the total score by the number of items, resulting in a 0–2 measure. Cronbach's alpha of the Spanish version of the instrument was 0.64.

- -

ER was assessed with the Emotional Recognition Test Faces,38,39 comprised of 20 photographs that express 10 basic and 10 complex emotions. Higher scores indicate better ER. Psychometric properties of the Spanish version show a Cronbach's alpha of 0.75.

- -

The attributional style was assessed with the Internal, Personal and Situational Attributions Questionnaire (IPSAQ).12,40 The IPSAQ has 32 items which describe 16 positive and 16 negative social situations. For each item the respondent is required to write down a single most likely causal explanation for the situation described. Two cognitive bias scores are derived from the six subscale scores: externalizing bias (EB) and personalizing bias (PB). The psychometric characteristics of the scale indicated a Cronbach's alpha was 0.719 for the externalizing bias and 0.761 for the personalizing bias.

Assessment of executive function included the following test with standardized scores:

- -

The Trail Making Test (TMT) is a test integrating two parts: part A measures the speed of processing and part B measures mental flexibility. We used TMT-B and the time taken to finish the task as a measure of cognitive flexibility.41 Is important to note that in this study, there was an inverse interpretation of the results for this task: the longer time taken to finish the task, the lower the degree of cognitive flexibility.

- -

Computerized version of Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (WCST)42 was used to assess EF in clinical settings. Total errors, perseverative and non-perseverative errors were used as a measure of cognitive flexibility.43

- -

Color-Word Stroop Test (Stroop Test Golden version, Spanish adaptation) was used to assess inhibitory response.44 Interference is calculated and together with word-color (WC) scores is used as an inhibitory control measure.

- -

The digit subtest of Wechsler Adults Intelligence Scale (WAIS-III)45 is comprised of two separate tasks: digit span forward task and digit span backwards. We used the digit span backwards task as a measure of working memory (WM).46

- -

The Vocabulary subtest from Wechsler Adults Intelligence Scale (WAIS-III)45 was demonstrated to be a measure of crystallized intelligence accurate enough to estimate premorbid IQ in FEP.47

The study was approved by the Research and Ethics Committees of Sant Joan de Déu (protocol code PIC-73-11 and date of approval 22nd November 2011). The research and ethics committees of every participating center in the study evaluated the project. Participants were informed about the aims of the study and signed informed consent for participation in the study. The mains studies were registered in the Clinical Trials registry with numbers of identifier: NCT02340559 and NCT04429412.

Statistical analysisDescriptive statistics were used to explore the sample. To compare mean differences between the variables, Student's t-tests were carried out for continuous variables and Chi-square tests to compare categorical variables. Associations between SC and EF were obtained using Pearson correlations. Finally, significant variables were included in the linear regression model using the stepwise method and adjusted by all variables found to be different between genders: level of education, age, diagnosis, and marital status. Symptoms were not included as no gender differences were found. The Statistics Program SPSS (version 26) was used for all analyses.

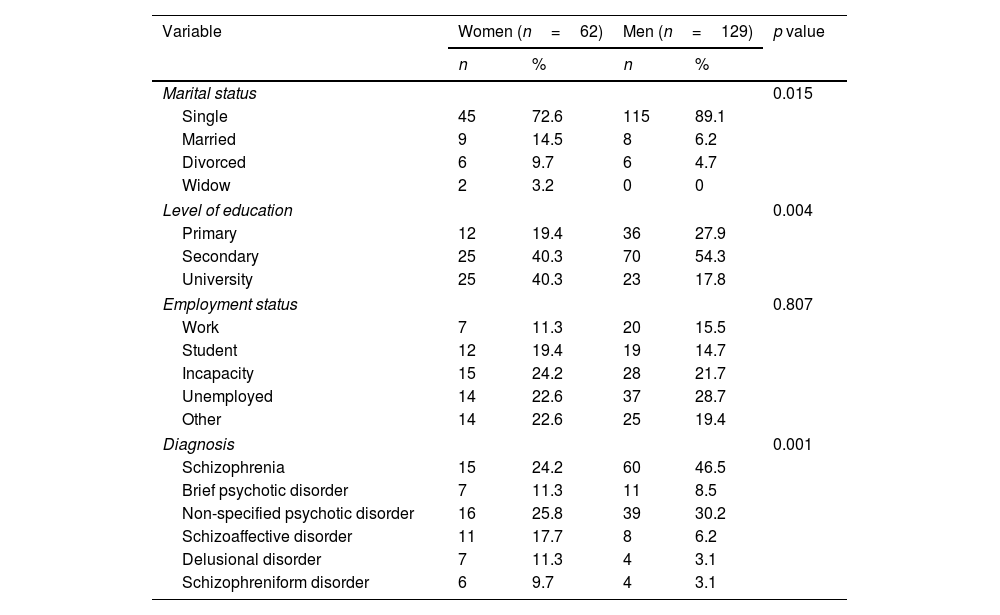

ResultsSociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the sampleTable 1 shows no gender differences in employment status, antipsychotic dose or estimated premorbid IQ. However, there were differences between women and men in age, marital status, level of education and diagnosis. Results show that the number of men with schizophrenia was higher than women while women had higher prevalence of schizoaffective, delusional or schizophreniform disorders. Women were significantly older (p=0.003) and had better performance in TMT-B than men (p=0.02).

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the sample.

| Variable | Women (n=62) | Men (n=129) | p value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Marital status | 0.015 | ||||

| Single | 45 | 72.6 | 115 | 89.1 | |

| Married | 9 | 14.5 | 8 | 6.2 | |

| Divorced | 6 | 9.7 | 6 | 4.7 | |

| Widow | 2 | 3.2 | 0 | 0 | |

| Level of education | 0.004 | ||||

| Primary | 12 | 19.4 | 36 | 27.9 | |

| Secondary | 25 | 40.3 | 70 | 54.3 | |

| University | 25 | 40.3 | 23 | 17.8 | |

| Employment status | 0.807 | ||||

| Work | 7 | 11.3 | 20 | 15.5 | |

| Student | 12 | 19.4 | 19 | 14.7 | |

| Incapacity | 15 | 24.2 | 28 | 21.7 | |

| Unemployed | 14 | 22.6 | 37 | 28.7 | |

| Other | 14 | 22.6 | 25 | 19.4 | |

| Diagnosis | 0.001 | ||||

| Schizophrenia | 15 | 24.2 | 60 | 46.5 | |

| Brief psychotic disorder | 7 | 11.3 | 11 | 8.5 | |

| Non-specified psychotic disorder | 16 | 25.8 | 39 | 30.2 | |

| Schizoaffective disorder | 11 | 17.7 | 8 | 6.2 | |

| Delusional disorder | 7 | 11.3 | 4 | 3.1 | |

| Schizophreniform disorder | 6 | 9.7 | 4 | 3.1 | |

| Women (n=62) | Men (n=129) | p value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| Age | 30.18 | 7.90 | 26.78 | 6.79 | 0.003 |

| Antipsychotic dose, mg/d* | 398.20 | 330.10 | 537.56 | 718.49 | 0.276 |

| BDI total | 15.93 | 9.51 | 14.97 | 9.06 | 0.504 |

| PANSS positive | 13.15 | 5.13 | 14.36 | 6.11 | 0.178 |

| PANSS negative | 14.06 | 5.75 | 15.59 | 6.45 | 0.116 |

| PANSS general | 29.47 | 8.55 | 29.34 | 8.56 | 0.924 |

| GAF | 61.68 | 12.56 | 61.08 | 12.94 | 0.815 |

| Estimated premorbid IQ | 99.77 | 16.57 | 95.34 | 14.36 | 0.072 |

| WAIS. Digits reverse order | 54.72 | 14.731 | 53.10 | 15.77 | 0.508 |

| TMT-B | 67.21 | 19.16 | 77.04 | 28.99 | 0.02 |

| WSCT total errors | 44.39 | 13.15 | 45.98 | 13.75 | 0.473 |

| WSCT perseverative errors | 44.79 | 13.69 | 47.38 | 13.60 | 0.246 |

| WSCT non-perseverative errors | 44.64 | 13.17 | 45.25 | 13.53 | 0.78 |

| Stroop word/color | 44.05 | 14 | 46.22 | 14.39 | 0.34 |

| Stroop interference | 52.94 | 10.77 | 54.66 | 10.83 | 0.321 |

BDI: Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-II); PANSS: Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale; TMT: Trail Making Test; WSCT: Wisconsin Card Sorting Test; estimated premorbid IQ calculated by vocabulary subtest WAIS-III.

Regarding symptom severity, there were no gender differences and recruited patients showed clinical stability, considering their PANSS scores were linked with low percentiles of symptoms. An exception was TMT-B: results showed differences in the performance of this test between women and men, with men having statistically significant worse performance.

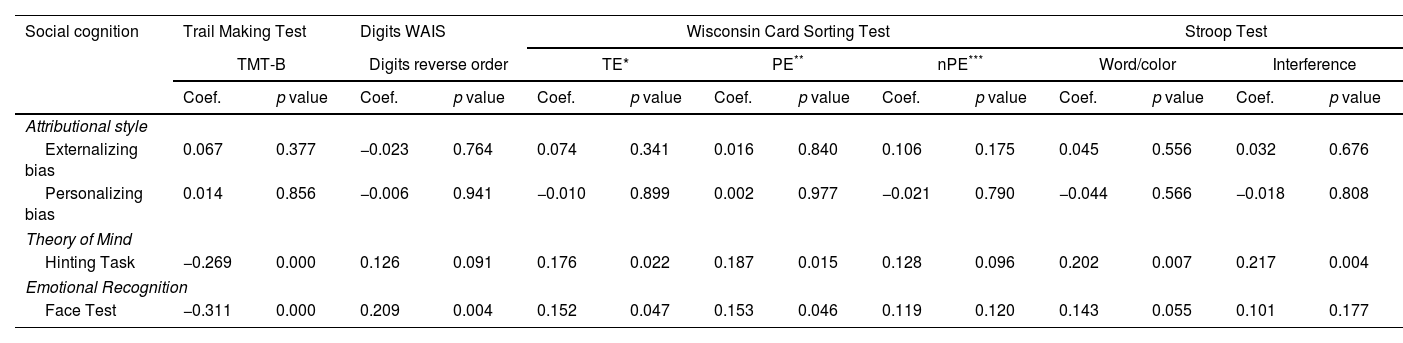

Relationship between executive function and social cognitionThe correlation between each domain of EF and SC is shown in Table 2. ToM was associated with cognitive flexibility (TMT-B p≤0.001), with WSCT total errors (p=0.022) and with WSCT perseverative errors (p=0.015). ToM was also related to inhibitory control as assessed by the Stroop Test; word/color (p=0.007) and interference (p=0.004). Regarding attributional style, none of the two biases (personalizing or externalizing) were related to EF. ER was linked to cognitive flexibility measured by the TMT-B (p≤0.001), WSCT total errors (p=0.047) and perseverative errors (p=0.046). Additionally, ER correlated with working memory, measured with the digit subtest in reverse order (p=0.004).

Correlation between social cognition and executive functions.

| Social cognition | Trail Making Test | Digits WAIS | Wisconsin Card Sorting Test | Stroop Test | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TMT-B | Digits reverse order | TE* | PE** | nPE*** | Word/color | Interference | ||||||||

| Coef. | p value | Coef. | p value | Coef. | p value | Coef. | p value | Coef. | p value | Coef. | p value | Coef. | p value | |

| Attributional style | ||||||||||||||

| Externalizing bias | 0.067 | 0.377 | −0.023 | 0.764 | 0.074 | 0.341 | 0.016 | 0.840 | 0.106 | 0.175 | 0.045 | 0.556 | 0.032 | 0.676 |

| Personalizing bias | 0.014 | 0.856 | −0.006 | 0.941 | −0.010 | 0.899 | 0.002 | 0.977 | −0.021 | 0.790 | −0.044 | 0.566 | −0.018 | 0.808 |

| Theory of Mind | ||||||||||||||

| Hinting Task | −0.269 | 0.000 | 0.126 | 0.091 | 0.176 | 0.022 | 0.187 | 0.015 | 0.128 | 0.096 | 0.202 | 0.007 | 0.217 | 0.004 |

| Emotional Recognition | ||||||||||||||

| Face Test | −0.311 | 0.000 | 0.209 | 0.004 | 0.152 | 0.047 | 0.153 | 0.046 | 0.119 | 0.120 | 0.143 | 0.055 | 0.101 | 0.177 |

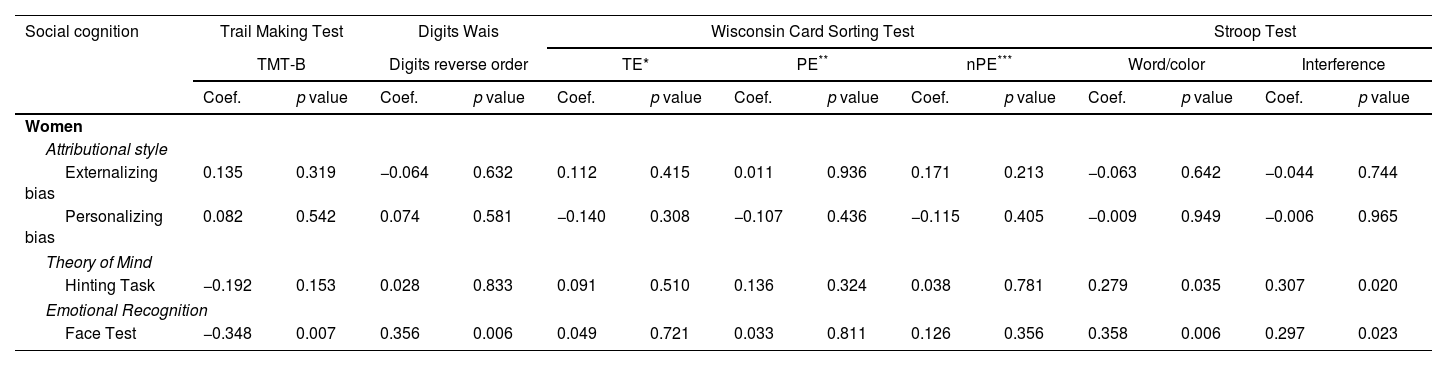

Table 3 shows the correlations between EF and SC split by gender. In the female sample, an association between the Hinting Task, used to assess ToM, and inhibitory control assessed by the word/color test (p=0.035) and interference (p=0.020) was found. Regarding ER, this subdomain correlated with cognitive flexibility as measured with the TMT-B (p=0.007), working memory (p=0.006) and inhibitory control, word/color test (p=0.006) and interference (p=0.023).

Correlation between social cognition and executive functions split by gender.

| Social cognition | Trail Making Test | Digits Wais | Wisconsin Card Sorting Test | Stroop Test | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TMT-B | Digits reverse order | TE* | PE** | nPE*** | Word/color | Interference | ||||||||

| Coef. | p value | Coef. | p value | Coef. | p value | Coef. | p value | Coef. | p value | Coef. | p value | Coef. | p value | |

| Women | ||||||||||||||

| Attributional style | ||||||||||||||

| Externalizing bias | 0.135 | 0.319 | −0.064 | 0.632 | 0.112 | 0.415 | 0.011 | 0.936 | 0.171 | 0.213 | −0.063 | 0.642 | −0.044 | 0.744 |

| Personalizing bias | 0.082 | 0.542 | 0.074 | 0.581 | −0.140 | 0.308 | −0.107 | 0.436 | −0.115 | 0.405 | −0.009 | 0.949 | −0.006 | 0.965 |

| Theory of Mind | ||||||||||||||

| Hinting Task | −0.192 | 0.153 | 0.028 | 0.833 | 0.091 | 0.510 | 0.136 | 0.324 | 0.038 | 0.781 | 0.279 | 0.035 | 0.307 | 0.020 |

| Emotional Recognition | ||||||||||||||

| Face Test | −0.348 | 0.007 | 0.356 | 0.006 | 0.049 | 0.721 | 0.033 | 0.811 | 0.126 | 0.356 | 0.358 | 0.006 | 0.297 | 0.023 |

| Social cognition | Trail Making Test | Digits Wais | Wisconsin Card Sorting Test | Stroop Test | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TMT-B | Digits reverse order | TE* | PE** | nPE*** | Word/color | Interference | ||||||||

| Coef. | p value | Coef. | p value | Coef. | p value | Coef. | p value | Coef. | p value | Coef. | p value | Coef. | p value | |

| Men | ||||||||||||||

| Attributional style | ||||||||||||||

| Externalizing bias | 0.065 | 0.486 | −0.006 | 0.944 | 0.058 | 0.545 | 0.024 | 0.803 | 0.074 | 0.443 | 0.102 | 0.272 | 0.071 | 0.447 |

| Personalizing bias | −0.024 | 0.795 | −0.036 | 0.697 | 0.082 | 0.395 | 0.086 | 0.371 | 0.047 | 0.624 | −0.075 | 0.420 | −0.049 | 0.595 |

| Theory of Mind | ||||||||||||||

| Hinting Task | −0.270 | 0.003 | 0.157 | 0.085 | 0.224 | 0.017 | 0.230 | 0.014 | 0.172 | 0.068 | 0.186 | 0.042 | 0.194 | 0.033 |

| Emotional Recognition | ||||||||||||||

| Face Test | −0.290 | 0.001 | 0.151 | 0.096 | 0.199 | 0.034 | 0.212 | 0.023 | 0.118 | 0.213 | 0.075 | 0.411 | 0.041 | 0.652 |

In the male sample, we found a negative correlation between ToM (Hinting Task) and TMT-B (p=0.003) and positive relationships between the Hinting Task and total and perseverative errors assessed with the Wisconsin Cards Sorting Test (p=0.017 and p=0.014 respectively), both of which measure cognitive flexibility. Moreover, a relationship was also found with inhibitory control (Stroop interference, p=0.033). The same association was found between ER (Face Test) and measures of cognitive flexibility (TMT-B p=0.001, WCST total errors p=0.034 and WSCT perseverative errors p=0.023). Finally in regard to attributional style (IPSAQ), only a negative correlation between internal attribution for negative events and inhibitory response (p=0.021) was found.

No correlations were found between any attributional biases and EF split by gender.

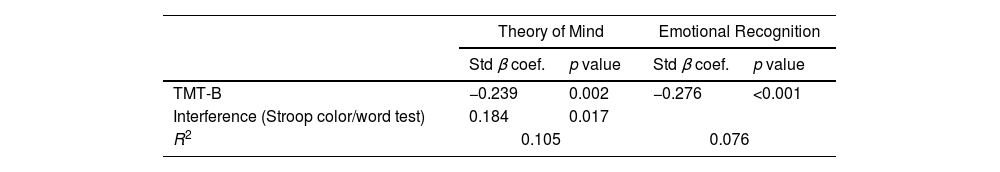

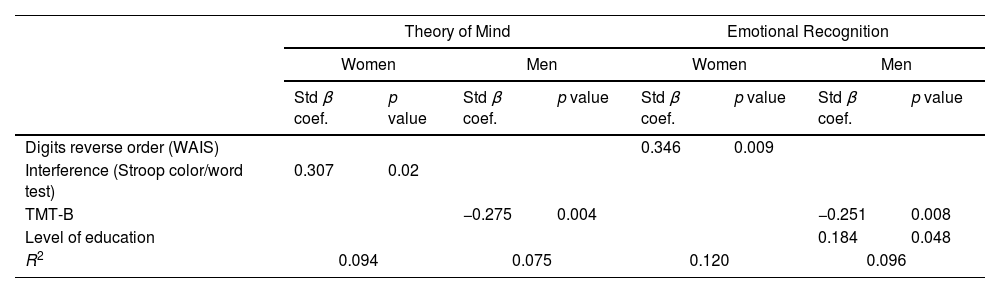

Linear regression modelTable 4 describes the linear regression model with EF variables as predictors and social cognition as the dependent variable.

Age, marital status, and diagnosis were not included as a significant variable in any of the following models.

A total of 7% of ER's variance was explained by TMT-B (p<0.001). A total of 10% of the variance of ToM was explained by TMT-B (p=0.002) and Stroop Test interference (p=0.017). Table 5 shows the linear regression model split by gender.

Linear regression model split by gender.

| Theory of Mind | Emotional Recognition | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women | Men | Women | Men | |||||

| Std β coef. | p value | Std β coef. | p value | Std β coef. | p value | Std β coef. | p value | |

| Digits reverse order (WAIS) | 0.346 | 0.009 | ||||||

| Interference (Stroop color/word test) | 0.307 | 0.02 | ||||||

| TMT-B | −0.275 | 0.004 | −0.251 | 0.008 | ||||

| Level of education | 0.184 | 0.048 | ||||||

| R2 | 0.094 | 0.075 | 0.120 | 0.096 | ||||

In the women sample, 9% of the variance in ToM was explained by Stroop Test interference (p=0.02), while 7% of the variance in ToM was explained by TMT-B (p=0.004) in the male sample. The reverse digits explained 12% of the variance in ER (p=0.009) in the sample of women. On the other hand, in the sample of men, 9% of variance in ER was explained by two variables, namely TMT-B (p=0.008), and level of studies (p=0.048).

DiscussionThe present study attempts to explore the associations between EF and SC in people with FEP. As a secondary aim, the impact of gender in these relationships was examined.

Regarding our first aim, a relationship between different domains of SC and some domains of EF was found, specifically, we found a relationship between ToM and cognitive flexibility and inhibitory control; and between ER and WM and cognitive flexibility. The results by gender show that there is a different profile of associations between EF and SC for women and men.

In relation to ToM and its relationship with EF, it is important to highlight that abnormalities in the prefrontal cortex (PFC) are present from early stages of psychosis48 and these abnormalities lead to PFC dysfunction, which could have a negative impact in areas of high cognitive resource consumption necessary in both SC and EF, implying a deficit in the ability to understand others, but also a poor performance in cognitive flexibility and inhibitory control.25,49

Relative to ER we found worse performance in cognitive flexibility had a negative effect in ER, which confirms findings by Yang et al.50 who revealed a correlation between deficits in emotional facial recognition and deficits in cognitive flexibility in people with FEP. Moreover, we found a correlation between ER and WM. Overall, our results are aligned with others that suggest WM could have an impact not only on ER, but also on the daily functioning of people with psychosis.51,52

Interestingly, although we obtained modest significant results regarding internal attribution for negative and positive events and inhibitory control, none of the attributional style biases correlated with EF. We speculate that this may be due to the characteristics of our sample. There are studies linking attributional style to the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC), temporoparietal junction (TPJ) and precuneus.53 Likewise, the mPFC is related to alterations in EF in patients with longer disease duration.54 As a result, due to this study's recruitment of patients with a recent onset of psychosis leads us to believe that the above-mentioned structures could be preserved, since the attributional biases studied are not evident, nor did FEP patients have a clinical alteration in the performance of the EF studied. Considering our results as a whole, we believe that more research is needed in order to explain their functional significance in the FEP population.

In addition, the regression analysis found that ToM could be explained by cognitive flexibility and inhibitory control. These results are consistent with those found by Fernandez-Gonzalo et al.,49 who concluded that a deficit in ToM could be associated with poorer performance on tests assessing cognitive flexibility and inhibitory control. Considering our results, this supports the idea of a key role of ToM as an important mediator in the relationship between neurocognition and social functioning as proposed by authors such as Hajdúk et al.26 Furthermore, we found that cognitive flexibility could explain a residual part of the variance in ER. To our knowledge, no other studies analyzed the role of cognitive flexibility in ER in FEP, further studies are needed to clarify the implications of these findings.

Regarding our secondary aim, our study also provides evidence in favor of gender differences in the relationship between EF and SC. On the one hand, women with low performance on cognitive flexibility tasks had worse ToM performance, and poor cognitive flexibility performance. WM and inhibitory control was also related to poor performance in ER. On the other hand, men with poorer cognitive flexibility and inhibitory control showed lower performance in ToM. Moreover, poorer performance in the cognitive flexibility subdomain showed low performance in ER in men.

Our results suggest that men and women with FEP may have a different association profile between SC and EF. Previous studies show partial results analyzing the relationship between gender and SC or between this variable and neurocognition. Regarding the relationship between gender and SC, Abu-Akel and Bo32 found higher global mental abilities in women with schizophrenia compared to their male counterparts. In this line, there are studies that found greater impairment in emotional processing in men than in women,31 although there are also studies that found no gender differences between different domains of CS.29,30 In our study, both ToM and ER were altered in women and men, but their relationship with cognitive function was different, which would suggest that the pathways of the relationship between SC and EF are different in men and women and these differences should be taken into account.

The linear regression model was also applied to the sample divided by gender and showed that in the women subsample, inhibitory control explains a small proportion of the variance in ToM, and ER is modestly explained by working memory. For men, cognitive flexibility explained a residual part of the variance in ToM, and a modest part of the variance of ER was explained by cognitive flexibility and educational level. This sociodemographic finding in the regression analysis is consistent with previous studies reporting that an earlier age of onset has a negative effect on prognosis by preventing patients from achieving socially established goals, such as mandatory education, entering in the labor market or having meaningful social relationships.55

To the best of our knowledge, these are the first results to report gender differences in the association between SC and EF. However, this should be further studied as there is evidence of gender differences in response to Metacognitive Training,56 and thus, differences in neurocognition and SC in men and women may influence their clinical response and treatment needs. Our results could be helpful when designing personalized treatment by considering the specific EF variables impacting each gender as relevant variables to improve psychological treatments addressed to improve SC.

In summary these findings add to the already growing evidence that executive functions play an important role in SC performance, and as Gardner et al.55 suggests, also have an impact on the daily life of people with FEP. In this line, we consider it is important to consider the relationship between SC and EF, not only in people with FEP and cognitive impairment, but also in patients with below-average cognitive performance as this study and other authors17,29 found worse performance in tasks used to measure EF correlate with poorer performance in tasks used to assess SC. This was true in both the complete sample and in the two gender samples in this study. In this line, and in agreement with other studies,57,58 the influence of psychotic symptomatology on the results of the cognitive assessment is also ruled out, given that the results of the PANSS reflect clinical stability in both positive and negative symptoms. These findings could be of great relevance for the design of therapeutic interventions that take executive functioning into account in SC training programs for FEP patients even without any cognitive deficit. Finally, it is also important to take into account the differences between women and men in the relationship between EF and SC in order to address the specific needs of each gender during the intervention.

LimitationsAlthough the present study has a strong experimental design with a large sample of subjects with FEP, results must be interpreted within certain limitations. The first limitation is that our data stems from two sources, each of which with a different number of items in the Hinting Task. Although we transformed the variable for comparison, it is possible that the different number of items may have affected the sensitivity of the test to true performance. Secondly, we did not include a control group, and in its absence, we cannot determine whether our results are specific to the FEP population. Thirdly, although the distribution of the sample in the study was not equitable with respect to gender, and it is a clear limitation of the study, it is representative of the clinical reality with respect to the sociodemographic characteristics of the patients attended. However, in the regression models by gender we found that the power of variables that explain SC in women and men are similar, though even higher in women. Our study had a cross-sectional design, so it would be interesting to include in the future follow-up studies that will allow us to assess causality between variables explored. Finally, results suggest that social functioning was not different between the women and men in the sample, however, this was assessed with the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) scale. So further studies should include more precise scales to assess psychosocial functioning and to explore the relationship between this concept, EF and SC.

Beyond these weaknesses, our study had a large sample of people with FEP, and to our knowledge, no other studies have focused in understanding the relationship between different domains of EF and SC, nor investigated whether there are gender differences in this relationship.

ConclusionsOur study shows a relationship between SC and EF, especially between ToM, emotion recognition and cognitive flexibility. While ToM is also related to inhibitory response, ER is related to WM. The main biases of attributional style do not seem to be related to EF.

We found that these patterns of associations are different for men and women.

Finally, we found that EF alone are modest but significant predictors of SC ability.

Therefore, these results should be considered when administering social cognitive interventions to people with psychosis, as people with specific deficits may benefit from including neurocognitive remediation focused on EF. Gender differences in the relationship between EF and SC should be taken into account in order address the specific needs of women and men in intervention programs.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflict of interests.

This work was supported by the Instituto de Salud Carlos III (Spanish Government), research grant number PI11/01347, PI14/00044 and PI18/00212 by the Fondo Europeo de Desarrollo Regional (FEDER), Progress and Health Foundation of the Andalusian Regional Ministry of Health, grant PI-0634/2011, Obra Social La Caixa (RecerCaixa call 2013), Obra Social Sant Joan de Déu (BML) and Health Department of Catalonia, PERIS call (SLT006/17/00231).

Spanish Metacognition Study Group (SMSG): Acevedo A, Alonso-Solís A, Anglès J, Ansó L, Argany MA, Aznar A, Barajas A, Barrigón ML, Beltrán M, Birulés I, Bogas JL, Cabezas A, Camprubí N, Carbonero M, Carrasco E, Casañas R, Cid J, Conesa E, Corripio I, Cortes P, de Apraiz A, Delgado M, Domínguez L, Escartí MJ, Escudero A, Esteban Pinos I, Franco C, Frigola-Capell E, Forns L, García C, Gonzalez-Casares R, González-Higueras F, González-Montoro MªL, González E, Grasa-Bello E, Guasp A, Gutiérrez-Zotes Huerta-Ramos ME, Huertas P, Jiménez-Díaz A, Lalucat LL, Legido T, LLacer B, López-Carrilero R, López-Frutos A, Lorente E, Luengo A, Mantecón N, Mas-Expósito L, Montes M, Montserrat C, Moreno-Kustner B, Moritz S, Murgui E, Nuñez M, Ochoa S, Palomer E, Peláez T, Planell K, Planellas C, Pleguezuelo-Garrote P, Pousa E, Renovell M, Rodríguez N, Rubio R, Ruiz-Delgado I, Salas-Sender M, San Emeterio M, Sánchez E, Sánchez-Alonso S, Sanjuán J, Sans B, Sió H, Teixidó M, Torres P, Vidiella M, Vila MA, Vila-Badia R, Villegas F.