The Salamanca Plaza Mayor is considered by many the most beautiful main square in Spain. For more than two and a half centuries it has been at the core of Salamanca's social and university life. As many other landmark monuments in the UNESCO World Heritage Old City of Salamanca, it was built using a honey-coloured, easy-to-carve but durable sandstone quarried from a municipality nearby, Villamayor de Armuña. It has a trapezoidal shape that Spanish novelist and essayist Miguel de Unamuno (1864–1936), who also served as Chancellor at the University of Salamanca, defined as “an irregular square, but amazingly harmonious.”

Fostered by chief magistrate and Spanish Crown representative in Salamanca Rodrigo Caballero y Llanes (1663–1740), Salamanca Plaza Mayor building works began in 1729. Architect Alberto de Churriguera (1676–1752) designed and implemented the original project; indeed, its distinctive Baroque style is called “Churrigueresco”. Following Churriguera's death, other architects were responsible for the project, which was completed in 1755 by Andrés García de Quiñones (1709–1784), who also designed The City Hall Pavilion for the north side of the square. The Salamanca Plaza Mayor has four three-story pavilions (or facades), with balconies and balustrades, that rest upon 88 semicircular arches. The spandrels between arches are decorated with medallions illustrating famous people in Spanish history. Some medallions are still uncarved, waiting to honour relevant people from the past, present or future history of Spain, as they are nominated by local institutions, such as the Salamanca City Council and the University of Salamanca. On Plaza Mayor's east side, The Royal Pavilion wears carved medallion reliefs of Spanish monarchs. Some royal medallions, such as the one depicting the current Spanish emeritus monarchs Juan Carlos I (1938-) and Doña Sofía (1938-), can be found at The City Hall Pavilion, which is also dedicated to other important non-royal personalities, or allegories of non-monarchical socio-political periods, such as the Spanish Republic. On the west side, The Petrineros Pavilion, which name recalls the leather tanners that used to trade in that place, shows medallions honouring other illustrious Spanish figures, including referents of Spanish literature, such as Fray Luis de León (1527–1591), Miguel de Cervantes (1547–1616) or Miguel de Unamuno. Opposite to The Royal Pavilion, the medallions at St Martin's Pavilion are devoted to Spanish conquerors and other prominent army leaders. Curiously, there is only one medallion portraying a non-Spaniard, Sir Arthur Wellesley (1769–1852), also known as the Duke of Wellington, in recognition for his service during the Spanish War of Independence (1808–1814) against Napoleonic troops. Notably, only 8 women are portrayed in these medallions: Isabel I de Castilla (1451–1504), alongside Fernando II de Aragón (1452–1516), both known as The Catholic Monarchs; their daughter Juana I de Castilla (1479–1555), also called Juana la Loca, whose face profile appears timidly behind his husband's, Felipe el Hermoso (1478–1506); religious sister and writer Santa Teresa de Jesús (1515–1582); Isabel de Farnesio (1692–1766), second wife of Felipe V (1683–1746), who first authorised the construction of Salamanca Plaza Mayor in 1710; Isabel II de España (1833–1868); Doña Sofía, with Juan Carlos I; and two allegories of The First (1873–1874) and The Second (1931–1939) Spanish Republic.1

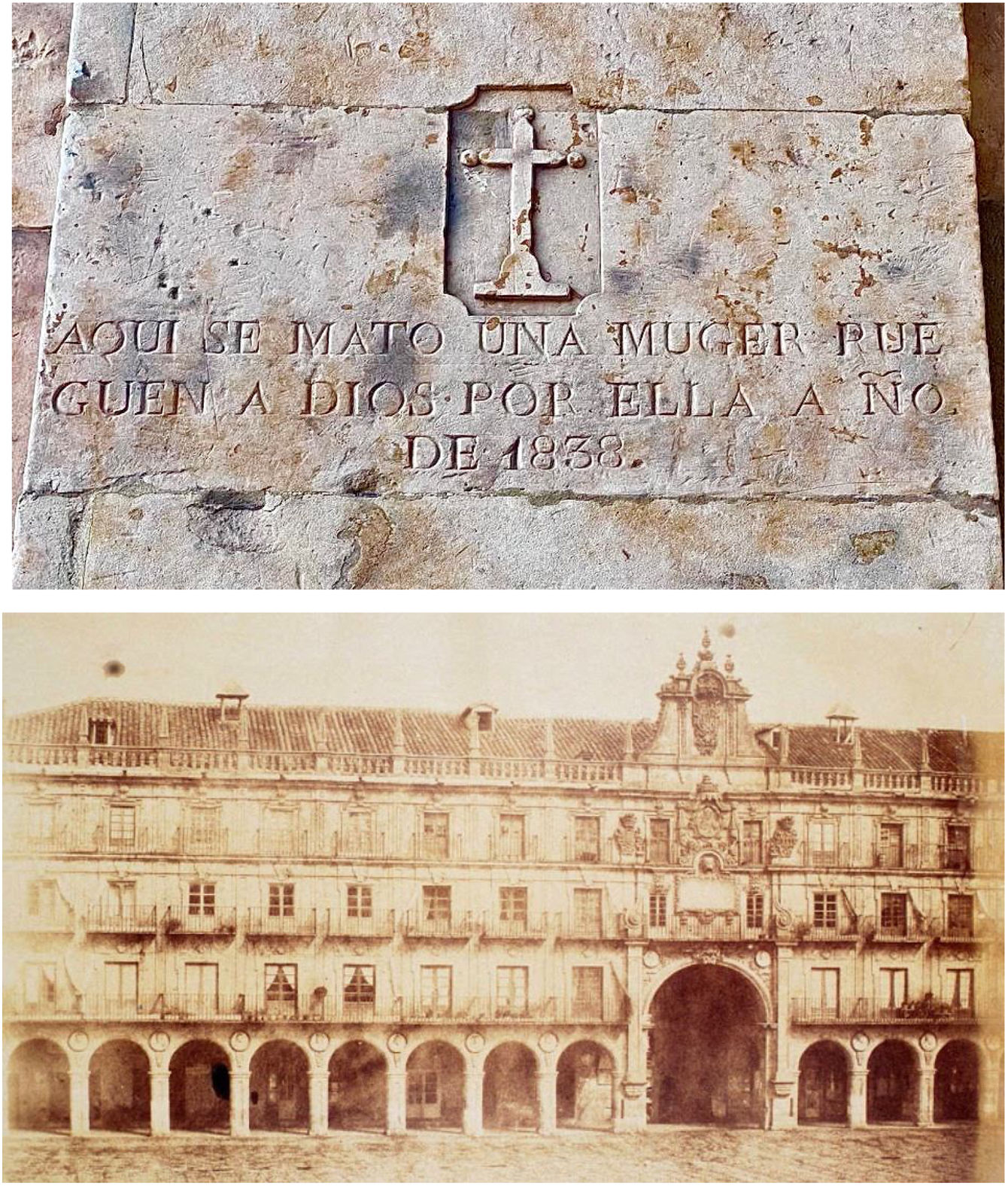

Nevertheless, albeit without a medallion, a ninth, anonymous woman is mentioned in a legend denoting an old socio-religious Spanish tradition that was forgotten over time. The visitor that enters Plaza Mayor through The Royal Pavilion, near Salamanca Central Food Market, may find Salamancan friends, who, for many years, get together, before going elsewhere in town, under an inscription carved on the inner side of one of the pillars that bears the weight that falls on the entrance arch. The engraving, written in capital letters, is under a Holly Cross, also carved on the stone, and reads (see Fig. 1): “Aquí se mató una mu(g)er, rueguen a Dios por ella. Año de 1838” [A woman killed herself here, pray to God for her. Year 1838]

Above: Current photograph of Salamanca Plaza Mayor engraving with the prayer request “A woman killed herself here, pray to God for her. Year 1838.” Below: Mid-19th Century calotype by Welsh photographer, resident in Spain, Charles Clifford (1819–1863). This is Salamanca Plaza Mayor first photograph, and shows The Royal Pavilion entrance, where the prayer request was engraved near the time Clifford took the picture. (Photograph published with permission of Archivo-Biblioteca de la Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando, Madrid).

Some of those friends could have arrived there after attending mass at St Julian and St Basilisa Church, located in a small square nearby called Sexmeros, which owes its name to officials that were in charge of the public administration for different territorial divisions in the region of Castile. In that square, on a wall in front of the Church, there is a similar engraving accompanied by another Holly Cross: “AD 1792. Aquí mataron a un hom(v)re, rueguen a Dios por él” [AD 1792. A man was killed here, pray to God for him]

Only a few more inscriptions such as these have survived the passage of time; they are in other cities across the Spanish geography, not only in Castile. In fact, several 17–19th Century renowned Spanish writers alluded to these prayer requests for unnamed people in their poems and other literary works, suggesting it was a widespread orally transmitted catholic tradition by which families and others, including the clergy, asked passers-by to pray for relatives, friends, or acquaintances, who died unexpectedly without having received the sacrament of extreme unction. Interestingly, all these engravings followed similar aesthetics and relatively homogenous writing patterns. They were nameless, maybe to hide identities that, in some cases, could simply have been unknown, or as part of the socio-religious tradition and the deceased social status; and described sudden, violent deaths succinctly. However, despite their briefness, grammar and verbal structures seemed to be carefully chosen to distinguish between self-inflicted or accidental deaths, and murders or deaths caused by others.

It is only from evidence in Spanish literature that we learnt about the likely purpose of these inscriptions and, thereby, one can surmise that some of these engravings referred to people that may have committed suicide. For example, Nobel Prize for Literature Juan Ramón Jiménez (1881–1958) intimated that suicide was behind some of these prayer requests.2 Also, perhaps to clarify the ambiguous Castilian language verbal expression “se mató”, which depending on the context may mean either suicide or accidental death, some inscriptions included the cause of death. For instance, Andalusian historian Teodomiro Ramírez de Arellano y Gutiérrez de Salamanca (1828–1909) described an engraving on the base of a wooden Holly Cross embedded in a wall of St Ana Church Convent in Córdoba that read3: “Aquí se mató un hombre que cayó de esta pared, rueguen al Señor por él. Año de 1677” [A man fell off this wall and died here, pray to the Lord for him. Year 1677]

Arguably, the lack of such explanatory text in Salamanca Plaza Mayor inscription, and the peculiar place where the woman died, may increase the likelihood that she killed herself intentionally, but we shall never know for certain. In fact, suicides were not officially reported in Spain until 1906, and 19th Century first European suicide scholars, such as Émile Durkheim (1858–1917), had already observed lower suicide rates in women, despite showing more self-harm ideas and behaviours4; a fact that has persisted to this day and has been called “the gender paradox” in suicide.5 Nonetheless, there is sufficient written recollection of popular beliefs to support that inscriptions with prayer petitions, such as hers, in Spain were used for those who self-harmed and killed themselves. During the 300 years these legends were engraved on public streets and building walls suicide was demonised by the Catholic Church. Thus, it is plausible that suicides were added to the wider pool of sudden, violent deaths that required those prayers; to redeem the deceased from a sinful act of free will that occurred before receiving the extreme unction. Given the strong influence of Catholic Church over socio-political life, the process of medicalisation of suicide in Spain was more tortuous than in other Western European countries6, where some examples of medical approaches to understand suicide were already reported in the 16th and 17th Century.7 It was mainly in the second half of the 19th Century when suicide in Spain was not exclusively attributed to free will, or other socio-religious interpretations, but also to medical causes. The Spanish adoption of mental degeneration theories, initially postulated by Bénédict Morel (1809–1873) in France, prompted to consider suicide among pathological manifestations of impulsivity, with underlying organic anomalies that might have a strong hereditary component and, therefore, be preventable. This contributed to a shift from the prevailing deeply theocratic, criminalised concept of suicide to a social testimony of what could be a consequence of mental illness.8 The gradual change in the interaction of modern Spanish society with the Catholic Church could also influence a quiet transition from long-lasting, deep-rooted religious behaviours, such as the inscriptions mentioned above for unexpected deaths, to new habits in accord with contemporary beliefs.

The 17–19th Century prayer requests, embodied in engravings, for those who died suddenly in a violent manner, represent yet another example of hitherto often undervalued popular customs that may be important to better comprehend the history of Spain. Indeed, historical chapters of the Spanish popular culture, instead of having been limited to informal accounts eventually consigned to oblivion, might have deserved carved golden Villamayor sandstone medallions in Salamanca Plaza Mayor to be imprinted forever on the collective memory.

Conflict of interestThe author declares that he has no conflict of interest.