Thank you very much and good morning to everyone. It is a pleasure to be on this important conference, on this important matter.

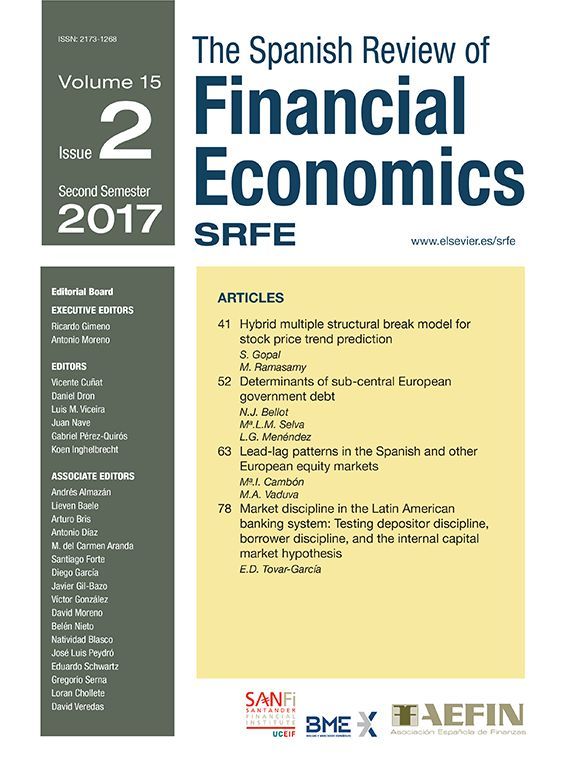

Recent developments in the euro area show a diverging path between the evolution of the real economy and lending dynamics. While GDP is recovering, credit to non-financial corporations continues contracting, as Graph 1 shows. In this context, if credit does not recover, logical concerns on economic prospects arise.

However, in my opinion, the analysis of credit developments and its implications for growth is not straightforward and before taking or recommending any policy action, a thorough examination of the factors explaining credit developments is required.

With this in mind, my contribution to this debate lies on providing an overview of the factors explaining credit behaviour (Section 2) and discussing possible policy actions based on the diagnosis that those factors suggest (Section 3). The analysis focuses on developments in the euro area, but this analysis is complemented in some particular aspects with evidence corresponding to the Spanish economy. I finalise my contribution summarising the main conclusions in the last section (Section 4).

2What factors explain credit behaviour?As mentioned before, in order to define the policy agenda, we need to first analyse the factors explaining credit behaviour. This implies analysing first the extent to which supply restrictions predominate or not over poor credit demand. If demand factors are relevant, then it has to be considered whether weak credit demand is associated to necessary corrections of imbalances. It is subsequently important to pay attention to whether we can expect recovery of credit demand before recovery of output, and finally whether we can identify specific supply frictions that need to be addressed.

2.1Can we disentangle credit demand from credit supply changes?Starting then with the first question on whether supply restrictions predominate or not over poor credit demand, we have to acknowledge that disentangling credit demand from credit supply changes is far from easy.

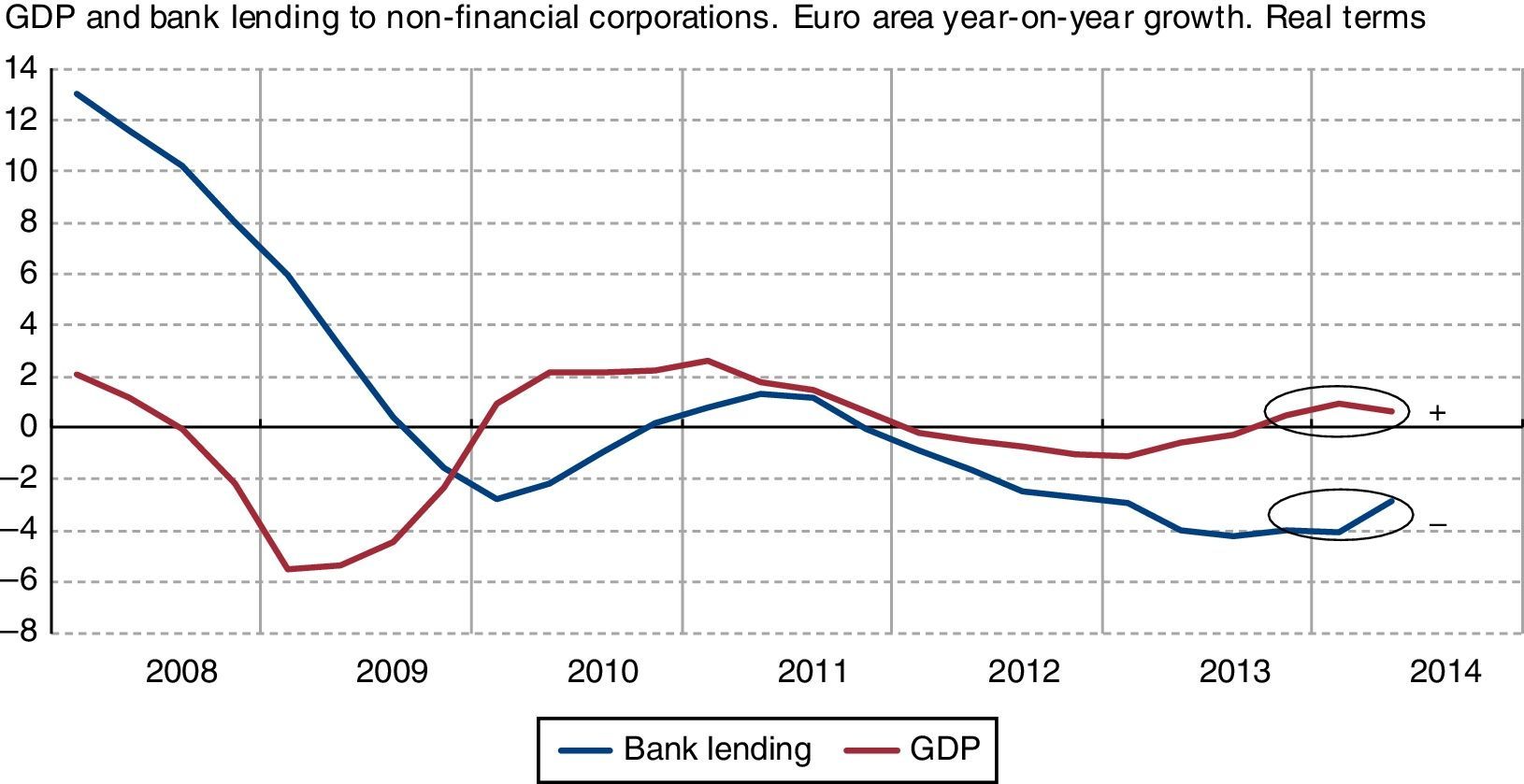

Having said that, and not wishing to extend too much going into a detailed description of supply and demand factors and its recent evolution,1 some insight can be provided turning to the Bank Lending Survey2 that asks participating banks to provide their views on developments in credit demand and supply. Graph 2 shows cumulated changes in demand and supply in the segment of lending to non-financial corporations in the euro area and Spain, extracted from such a Survey, i.e. it shows the result of accumulating over time the changes in demand and supply that the Survey provides for each quarter.

These cumulated changes reveal that during the crisis the weak bank lending to non-financial corporations has been driven by both demand and supply factors, in Spain as well as in the euro area. More recently, there are some signs of a mild recovery in both demand and supply. But current levels are still significantly below the pre-crisis levels.

In light of these data, it seems reasonable to consider that supply restrictions do not necessarily predominate over poor credit demand. On the contrary, demand factors appear to be very relevant.

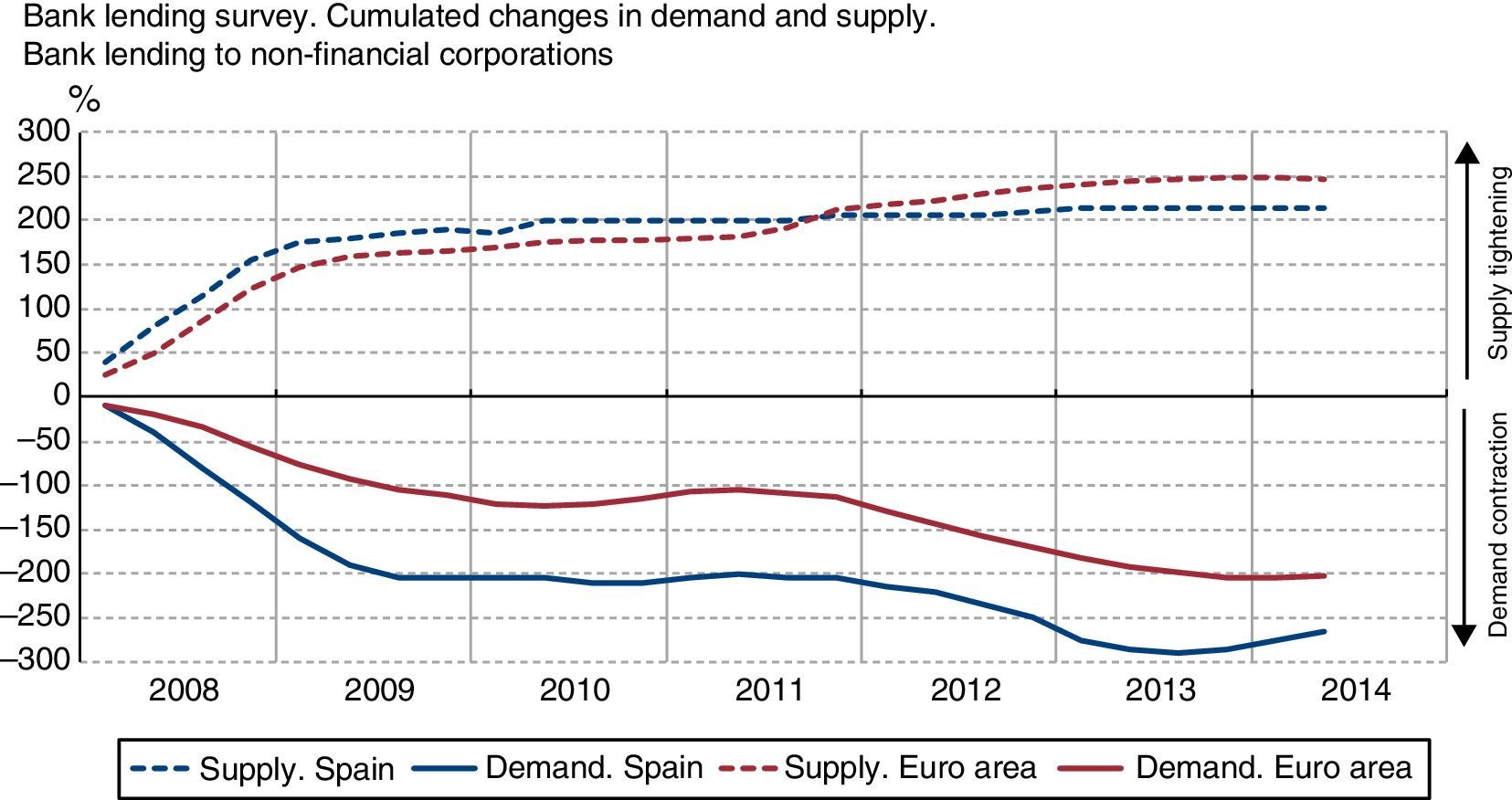

2.2Correction of imbalancesSecondly, one might wonder to which extent weak credit demand is associated to necessary corrections of imbalances. Excessive indebtedness could potentially be one of the imbalances that underlie the weak credit demand, especially in countries such as Spain where bank lending grew more significantly during the pre-crisis period. As a matter of fact, the high indebtedness of the Spanish private sector was one of the main disequilibria accumulated by the Spanish economy during the boom. For non-financial corporations, as Graph 3 shows, indebtedness grew rapidly during the expansion and reached peak values around 145% of GDP in 2010, compared to values around 100% of GDP in the euro area. The need to correct this disequilibrium is a key factor to explain credit behaviour in the country. The correction process has advanced but has not been completed yet, which implies that credit demand will continue to be weak for some time.

But this does not mean that every non-financial corporation has to deleverage. The implications of aggregated deleveraging for GDP growth will depend on how it is spread among (more and less productive) firms. A more disaggregated approach can shed highly valuable light.

In fact, such an approach shows, in the case of Spain, that debt contraction is not taking place across the board. In particular, the micro-data evidence shows that credit falls mainly for less healthy non-financial corporations (i.e. those which have a lower profitability, higher indebtedness, are less export-oriented and have a less dynamic behaviour in employment and sales).3 These results suggest that a healthy reallocation of debt seems to be taking place within the Spanish corporate sector.

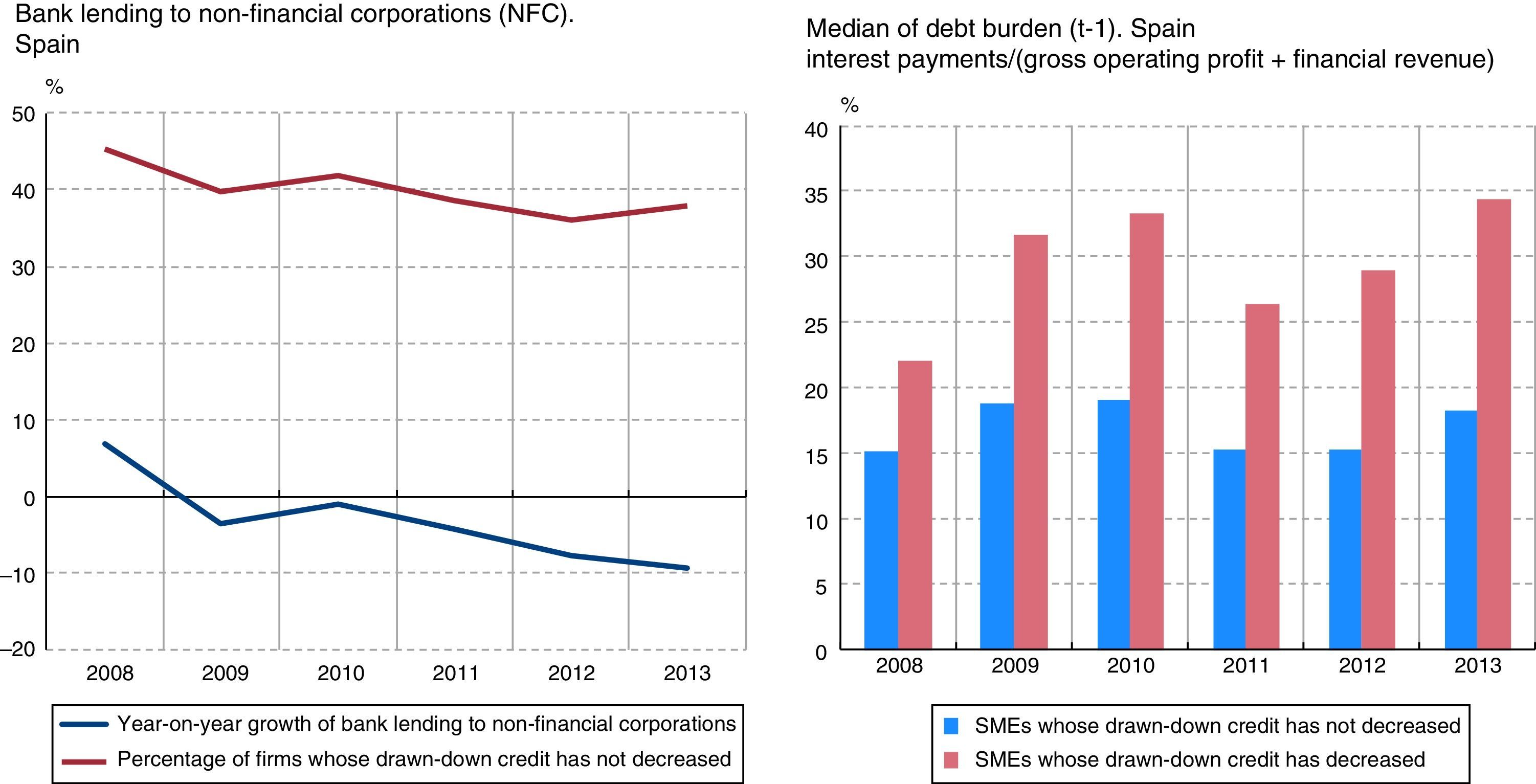

To illustrate this it can first be noticed that the contraction of aggregated bank lending to Spanish non-financial corporations has been compatible with the existence of a significant proportion of firms whose bank lending stock has not fallen. As shown in Graph 4, this percentage fell during the crisis but has always been above 35%, and more recently, there are some signs of reversal in this downward path.

Second, using the debt burden – measured as the ratio of interest payments to income – as a sort of summary indicator of the financial health of a company, it can be observed that the median value of this variable was, at t−1,4 much lower for firms whose bank lending stock has not fallen in period t than for firms whose bank lending stock has fallen in that period (see Graph 4). Considering that this indicator is a good summary indicator of the financial health of a company, since it combines profitability, indebtedness and funding cost, the above evidence suggests that those firms whose bank lending stock has not fallen tend to be healthier than firms whose bank lending stock has fallen.

2.3Does credit typically lead recovery?According to Kannan (2012),5 credit does not always lead recovery. In fact, lagged credit recoveries are more frequent than usually thought, especially after a financial crisis. The recent crisis fits this pattern well, both in industrialised and in emerging market economies.

In Spain, the recent pick up in GDP has not yet been followed by a parallel rise in bank loans. During the financial crisis, there has been a significant increase in the use of internal funding (mainly via retained profits) whereas bank credit has lost relative weight. This has been possible against a context of rising profit shares and diminishing dividend pay-outs.

2.4Supply frictionsPrevious analysis suggests that demand factors have played a significant role in the credit contraction. Having said that, attention must also be paid to whether there are specific supply frictions that can exacerbate credit contraction and/or hamper the healthy reallocation of debt.

One friction in this regard is the asymmetric information problems, which help to explain why small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) have a more difficult access to bank lending. The quality and quantity of relevant information available to assess the creditworthiness of firms is much lower for them than for large companies. This is a structural problem that in periods of crisis and uncertainty becomes more acute.

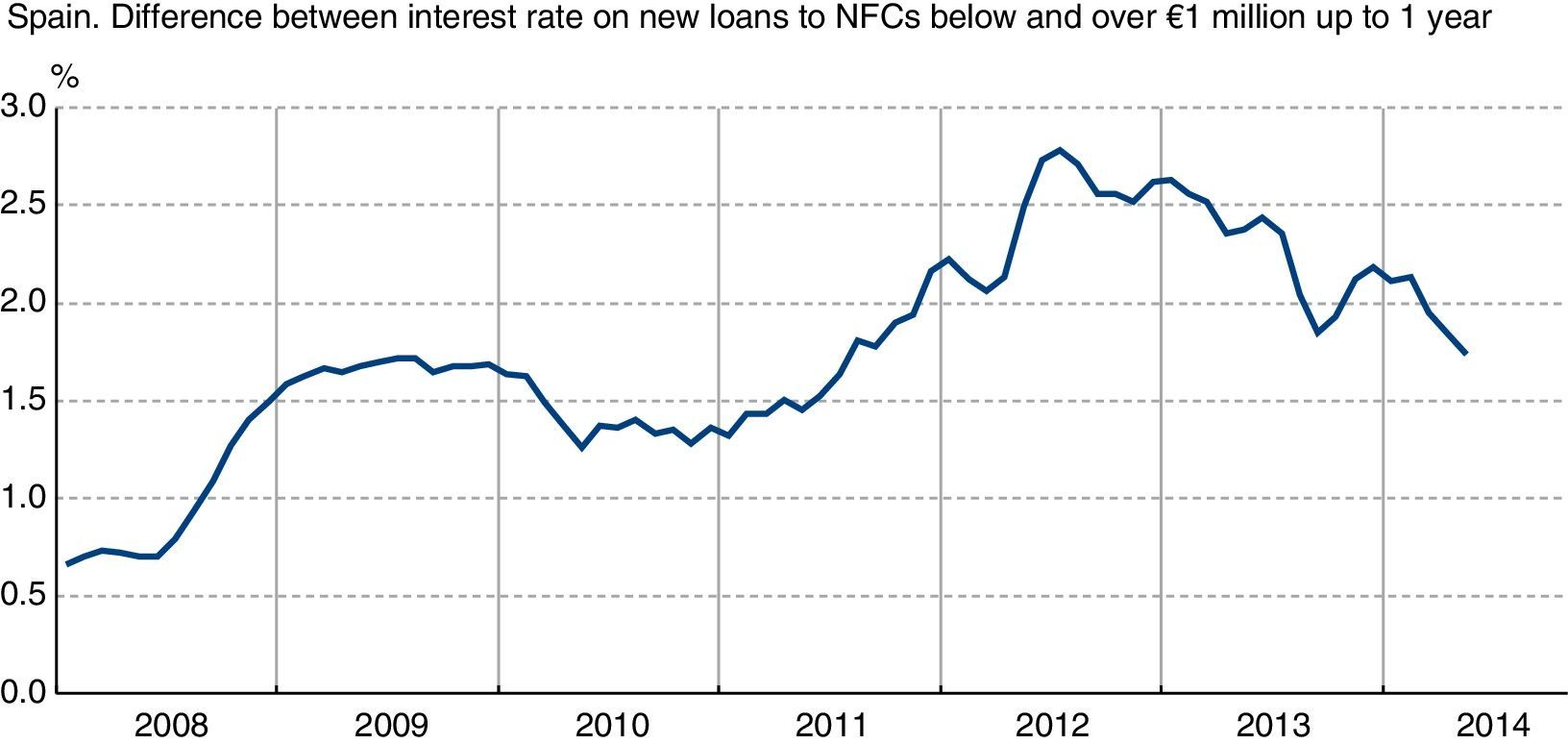

Graph 5 illustrates this by comparing the cost of bank lending between SMEs and large firms (proxied by the size of the loan) in Spain. In particular, it can be seen that the spread between the interest rate charged by banks to SMEs and that charged to large companies has risen significantly since the start of the crisis suggesting that access to bank lending has deteriorated significantly more for SMEs than for large companies.

A second friction relates to difficulties by banks to smoothly adjust to new banking regulations. This friction may imply an excessive deleveraging. In particular, when they face difficulties to properly manage credit risk. The absence of active securitisation markets does indeed constitute a relevant obstacle for an efficient management of credit risk by financial institutions.

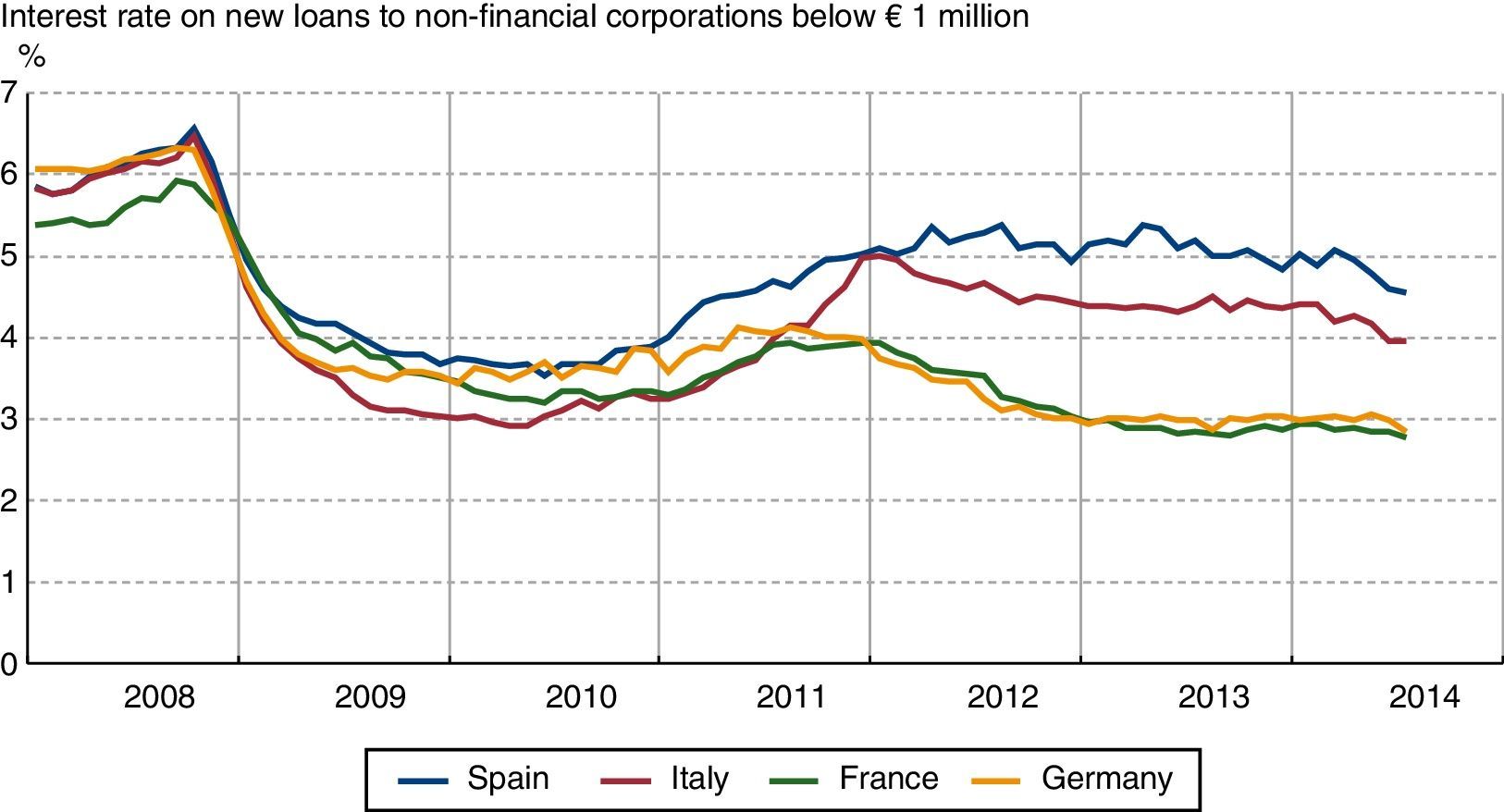

Finally, another important friction is financial fragmentation in the euro area. Financial fragmentation materialises in funding costs depending not only on the creditworthiness of the agents but also on their nationality. In particular, the cost of debt for Spanish and Italian banks is higher than the cost of comparable banks in the core euro area countries. These higher costs are passed through to their lending operations meaning that the cost of bank lending is higher in Spain and Italy. The existence of financial fragmentation therefore means that monetary impulses are not evenly transmitted across the euro area.

Graph 6 illustrates this in the case of SMEs, a type of companies that tend to rely more on bank lending since their direct access to markets is not normally possible due to size constraints.6 The spreads of the cost of bank lending to SMEs between Spain and Italy, on the one hand, and other countries such as Germany and France, on the other, have widened significantly since 2010 in parallel with tensions in the sovereign debt markets, but interestingly not in 2008 when the crisis started. More recently, some compression in the spreads has been observed consistent with the trend of partial re-integration of financial markets. But these spreads are still too high.

3Policy actionsThe above discussion offers some grounds to infer policy actions to revive credit markets. In particular, policy actions which would be worth exploring encompass those addressing the supply-side frictions that affect SMEs more adversely. This would include measures promoting the availability of information and analysis on SMEs, or actions reactivating Asset Backed Securities (ABS) markets on a sounder basis. Initiatives along these lines can be found on both fronts.

In particular, regarding the promotion of the availability of information and analysis on SMEs, both public and private initiatives exist, an example of the public ones being the work undertaken by the European Commission. In its Communication to the European Parliament and the Council on Long-Term Financing of the European Economy (March 2014), the European Commission recorded as actions for the Commission services “to undertake a mapping of the EU and national legislation and practices affecting the availability of SME credit information […]”, and “to revive the dialogue between banks and SMEs with the aim of improving financing literacy of SMEs […]” and “to assess best practices on helping SMEs access to capital markets”.

On the private side, the joint work done by Bain & Company and the Institute of International Finance proposes some actions to improve the availability of information on the creditworthiness of SMEs (see report “Restoring financing and growth to Europe's SMEs”, October 2013).

With regards to measures to reactivate ABS markets on a sounder basis, it is worth mentioning the work at international level on defining simple and transparent securitisations7 and the efforts at EU level to promote a better functioning of the securitisation market in the EU, which can be exemplified by those led by the ECB and the Bank of England.8

Other policy actions that may also help to revive credit markets include those facilitating debt restructuring by improving bankruptcy legislation and those tackling directly financial fragmentation, such as the completion of the banking union, or those mitigating their effects through non-conventional monetary policy measures.

On the contrary, more caution should be put with respect to actions that imply risk-taking by governments due to fiscal challenges and adverse selection problems. Similarly, relaxing regulation does not seem a good option in the current context, where the focus should be in having safer and better capitalised banks able to afford the credit risk that they are taking. Finally, with regards to funding for lending schemes, over-optimism should be avoided, as liquidity is already largely available and inexpensive.

4ConclusionsThe issue of how to revive credit markets is an important but complex problem which admits no straightforward policy response. To the extent that demand factors (e.g. deleverage) predominate, the case for bold public policy action is not always evident. Targeting credit growth may indeed be counterproductive if it entails excessive risk taking by banks or governments and distorts incentives for necessary deleveraging.

In these situations, it would be better to target frictions that affect credit supply (including reactivating ABS markets and eliminating financial fragmentation), and to manage properly agent's expectations, remembering that sustainable recovery of credit may require first a sufficient improvement of economic conditions.

A detailed description of the credit evolution in Spain can be found in Ayuso, J. (2013), “An analysis of the situation of lending in Spain”, Economic Bulletin, October 2013, Banco de España.

Written version of the remarks made by the Deputy Governor of the Banco de España, Fernando Restoy, published in the corresponding seminar volume. IMF-BoS High Level Seminar on Reinvigorating Credit Growth in Central, Eastern and Southern European Economies, held on 26 September 2014 in Portoroz, Slovenia.

The Bank Lending Survey is an official quarterly survey that has been conducted in coordination by all the euro area national central banks and the European Central Bank (ECB) since January 2003. The Survey asks a representative group of credit institutions about the changes in their lending policies and perceived demand, distinguishing between three market segments: non-financial corporations, households for house purchase, and households for consumption and other purposes. They are likewise asked about their forecasts for the following three months. Aggregate results for the euro area are regularly published on the ECB website: https://www.ecb.europa.eu/stats/money/surveys/lend/html/index.en.html. The results for the participating Spanish institutions are published on the Banco de España's website: http://www.bde.es/webbde/en/estadis/infoest/epb.html. Additionally, quarterly articles in the Economic Bulletin of the Banco de España summarise the results of the Survey corresponding to the participating Spanish institutions and compare them to the results corresponding to the euro area.

A detailed disaggregated analysis can be found in Martínez, C., Menéndez, A. and Mulino, M. (2014) “A disaggregated analysis of recent developments in lending to corporations”, Economic Bulletin, June 2014, Banco de España.

Debt burden is computed at t−1 rather than at t to mitigate endogeneity problems.

Kannan, P. (2012), “Credit conditions and recoveries from financial crisis”, Journal of International Money and Finance.

The cost of bank lending for these companies is proxied again by loans below 1 million euro.

The cross-sectoral Task Force on Securitisation Markets co-leaded by the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS) and the International Organization of Securities Commissions (IOSCO) was mandated, amongst other, to develop criteria to identify and assist in the development of simple and transparent securitisation structures.

See Bank of England and ECB (2014) “The case for a better functioning securitisation market in the European Union”, A Discussion Paper.