Oral mucosal grafts are essential in reconstructive urology, particularly for urethral and genital defects. Advances in harvesting and implantation techniques have been made, yet perioperative care remains crucial for optimal outcomes. This systematic review explores postoperative care pathways following oral mucosal graft harvesting to consolidate knowledge, identify best practices, and highlight research gaps.

ObjectiveThe review aims to identify optimal care pathways, compare different oral care approaches, and address research gaps.

MethodsA systematic literature search was conducted using PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science databases without time constraints. Key search terms included “oral mucosal graft”, “oral care pathways”, “OMG post-operative care”, “BMG”, “LMG”, and “OMG graft harvesting”. Selection followed PRISMA guidelines. Inclusion criteria focused on studies addressing oral mucosal grafts in reconstructive urology and associated perioperative care, excluding non-English articles, case reports, and editorials.

ResultsThe review underscores the suitability of oral mucosa for grafting due to properties like excellent vascularization and minimal immunogenicity. Comparisons among graft harvesting sites reveal differences in tissue quality, ease of harvest, and donor site morbidity. Non-closure techniques generally result in less postoperative pain and quicker healing, though closure might better control bleeding and infection. Despite common complications such as mild trismus and altered chewing efficiency, patient satisfaction remains high.

ConclusionsEffective management of oral mucosal grafts harvesting emphasizes tailored perioperative care to minimize complications and enhance recovery. Further research should focus on long-term oral morbidity, standardized care protocols, and patient-reported outcomes to improve care pathways and surgical results.

Los injertos de mucosa oral constituyen un elemento esencial en el campo de la urología reconstructiva, especialmente para el tratamiento de defectos uretrales y genitales. Aunque se han producido avances en las técnicas de extracción e implantación, el manejo perioperatorio sigue desempeñando un papel crucial en la obtención de resultados óptimos. Esta revisión sistemática explora las vías clínicas para el cuidado postoperatorio tras la extracción de un injerto de mucosa oral, con el fin de consolidar los conocimientos, identificar las mejores prácticas y arrojar luz sobre los vacíos de investigación.

ObjetivoEl objetivo de esta revisión es identificar las vías de atención óptimas, comparar diferentes enfoques para el cuidado oral y abordar los vacíos existentes en la investigación.

MétodosSe realizó una búsqueda bibliográfica sistemática en las bases de datos PubMed, Scopus y Web of Science sin limitaciones de tiempo. Los términos clave de búsqueda incluyeron «oral mucosal graft», «oral care pathways», «OMG post-operative care», «BMG», «LMG» y «OMG graft harvesting». La selección se realizó según las directrices PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses). Se incluyeron los estudios que abordaban el uso de injertos de mucosa oral en urología reconstructiva y las medidas de cuidado perioperatorio asociadas, y se excluyeron los artículos no redactados en inglés, los informes de casos y los editoriales.

ResultadosLa revisión pone de manifiesto la idoneidad del injerto procedente de mucosa oral gracias a sus propiedades de excelente vascularización e inmunogenicidad mínima. Las comparaciones entre las distintas zonas donantes de injertos desvelan diferencias en la calidad del tejido, la facilidad de extracción y la morbilidad de la zona donante. Aunque se cree que el cierre del lecho quirúrgico podría mejorar el control de la hemorragia y de las infecciones, las técnicas de cicatrización por segunda intención suelen producir menos dolor postoperatorio y una cicatrización más rápida. A pesar de las complicaciones habituales, como el trismo leve y la alteración de la eficacia masticatoria, la satisfacción de los pacientes sigue siendo alta.

ConclusionesEl abordaje eficaz de la extracción de injertos de mucosa oral destaca la necesidad de unos cuidados perioperatorios individualizados para minimizar las complicaciones y optimizar la recuperación. Los estudios futuros deben centrarse en la morbilidad oral a largo plazo, los protocolos de atención estandarizados y los resultados comunicados por los pacientes para mejorar las vías de atención y los resultados quirúrgicos.

Oral mucosal grafts (OMG) have become an indispensable tool in the field of reconstructive urology, revolutionizing the treatment of complex urethral and genital defects. These grafts, primarily derived from the oral cavity, offer unique qualities that make them ideal for repairing or replacing damaged urological tissues. In the established nomenclature of dental anatomy, the term ‘buccal mucosa’ is defined as the oral mucosa that covers the inner surfaces of the cheeks within the oral cavity. Conversely, ‘labial mucosa’ describes the mucosa lining the inner aspect of the lower lip, particularly overlying the alveolar ridge. ‘Lingual mucosa’ is used to denote the mucosal layer covering the tongue. These anatomical regions are collectively encompassed under the term ‘oral mucosal grafts’ when referred to in the context of grafting procedures.

The versatility of OMG, coupled with their favorable outcomes, has prompted a surge in their use in surgical procedures designed to restore both form and function to the genitourinary tract. This method's concept has been known for roughly eight decades, as already in 1941 Humby suggested the use of buccal mucosa in the repair of hypospadias.1 However, the use of oral mucosa in reconstructive urology became widespread only after reports by Burger et al. and Dessanti et al.2,3 While the surgical techniques for harvesting and implanting OMG have evolved, the critical aspects of postoperative care pathways deserve equal attention. The success of reconstructive urology procedures employing OMG is not solely determined by the surgical procedure itself but also by the meticulous care provided during the postoperative phase.

ObjectiveWhile there is a wealth of literature on the surgical techniques and outcomes of OMG urethroplasty, there is a noticeable gap in comprehensive reviews focusing specifically on postoperative oral care pathways. This oversight is significant, considering the integral role of perioperative care in patient recovery and the overall success of the surgical procedure. This systematic review aims to consolidate current knowledge and practices regarding oral care following OMG harvesting. It seeks to identify best practices, compare different oral care approaches, and highlight areas needing further research by examining various studies.

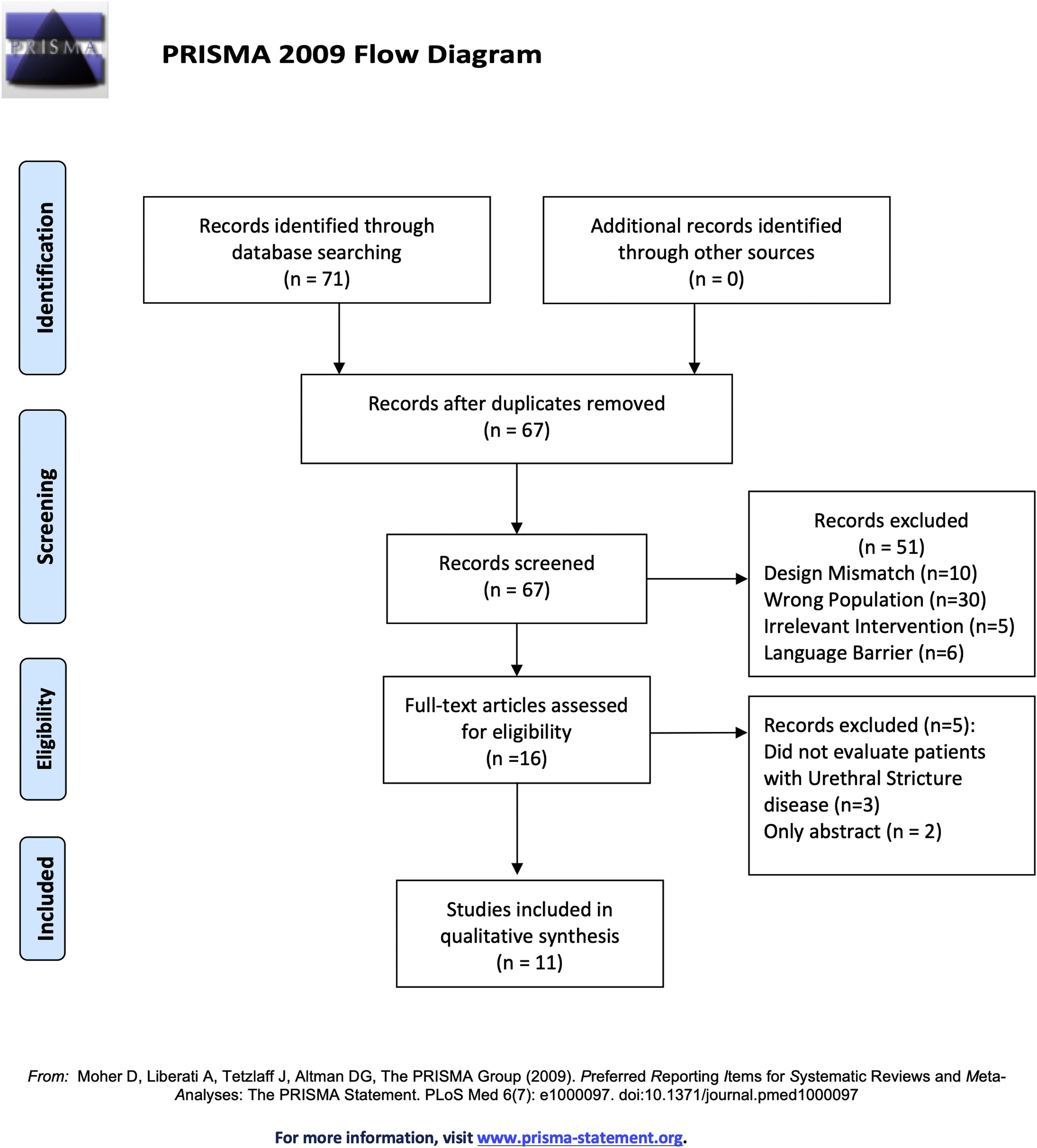

Acquisition of evidenceThe methodology for this systematic review was structured to encompass a comprehensive approach. The initial phase involved a detailed literature search without a time limit, using databases: PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science. Key search terms included “oral mucosal graft”, “oral care pathways”, “OMG post-operative care”, “BMG”, “LMG”, “OMG graft harvesting”. Two independent researchers (MF and LB) followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) statement. The process of selecting articles is presented in the PRISMA flowchart (Fig. 1).4,5 Inclusion criteria were defined to select studies that addressed OMG in reconstructive urology, including perioperative care and complications associated with OMG harvesting. Exclusion criteria eliminated articles not in English, case reports, and editorials. Discrepancies were resolved through discussion, with MW as an arbitrator if needed. Data extraction was systematically performed by MF and LB using a standardized form to ensure consistency and accuracy.

This process ensured a comprehensive overview of the current literature, facilitating a systematic review that synthesized existing knowledge and identified gaps for future research.

Synthesis of evidenceCharacteristics of the oral mucosaIn reconstructive urology, the application of OMG has extended to addressing a wide range of conditions, including urethral stricture disease, hypospadias repair, and genital reconstruction following trauma or congenital abnormalities. These grafts offer the advantages of excellent vascularization, minimal immunogenicity, and mucosal characteristics that closely resemble the target tissues.6 The mucosa consists of a thick, non-keratinized, stratified squamous, avascular epithelium and a slightly vascular underlying lamina propria. As demonstrated by immunohistochemical staining, angiogenesis and revascularization of the tissue after grafting are facilitated by the infiltration of blood vessels and nerve fibers from the submucosa into the lamina propria. These properties contrast with those of the bladder mucosa and penile skin, which have a thin epithelium and a thick lamina propria.7 Filipas et al. histologically compared the healing of OMGs and full-thickness skin grafts following implantation in the bladders of mini-pigs. Visual inspection revealed that full-thickness skin grafts had far higher levels of necrosis, graft ulceration, and inflammatory cell infiltration than OMGs.8 Inflammatory infiltration of the OMG is rarely reported despite the presence of polymicrobial flora, predominantly streptococci, on the oral epithelium. Mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT), a specialized immune system, and continuous exfoliation are two ways mucosal epithelial cells of the oral cavity prevent microbial colonization.9

Optimizing oral mucosa graft harvesting for urethroplastyOver the years, techniques for OMG harvesting and subsequent oral care have advanced, emphasizing the importance of adequate perioperative oral care to promote healing and reduce complications. Options for harvesting OMG for urethroplasty include buccal mucosa graft (BMG) harvested from the inner lining of the cheek, sublingual mucosa graft (SlMG) harvested from the tongue, and labial mucosa graft (LMG) harvested from the inner lining of the lip. All of these options offer both advantages and disadvantages in terms of tissue quality, ease of harvest, donor site morbidity, and graft characteristics, which should be considered based on individual patient factors and surgeon’s preference.6,10,11

Buccal mucosa grafts present a thinner muscular layer and thicker epithelium and submucosa layers, but the clinical meaning of these findings is unknown. Typically, SlMG are longer but narrower than BMG hence, as a conventional criterion, BMG are chosen for extensive defects, typically those with a total length of 6 cm or shorter. In cases of longer defects, such as panurethral strictures, SlMG is generally favored.10 However, it is worth noting that, as far as surgical outcomes are concerned, the available study results indicate similar efficacy of urethroplasties in 1-year follow-up regardless of the type of OMG used.12

Anatomical considerations of the oral mucosaBuccal mucosa graftClinically, BMG is favored for its toughness and elasticity, ease of harvest and handling, and the cosmetic advantage of leaving no visible scars at the donor site, which are critical considerations in surgical applications such as grafting. The vascularization of the buccal mucosa is robust, deriving from multiple arterial sources. These include the buccal artery, which is a branch of the maxillary artery; the anterior superior alveolar artery, coming from the infraorbital artery; the middle and posterior superior alveolar arteries and supplemental vessels from the transverse facial artery, which is a branch of the superficial temporal artery. This extensive vascular supply contributes to the buccal mucosa's resilience and durability; however, it also predisposes the area to post-harvesting hematomas due to the likelihood of vascular injury, as illustrated in Fig. 2. The buccal mucosa receives its primary sensory innervation from the long buccal nerve, which is complemented by the anterior, middle, and posterior superior alveolar nerves, all of which are branches of the second division of the trigeminal nerve. Additionally, there is minor sensory innervation contributed by the facial nerve, suggesting a complex innervation pattern that supports the sensory functions of this region. Although rarely reported, loss of sensation is a potential complication due to surgical incisions affecting branches of the facial or trigeminal nerves. Many studies examining complications associated with BMG highlight that these issues often correlate with several factors: the size and shape of the graft, the choice between open-wet or closed (occlusive) dressing methods for the graft wound, and the specific site of graft harvesting.13–16

Sublingual mucosa graftThe lingual mucosa, similar in structure to the mucosa found elsewhere in the oral cavity, covers the inferior lateral surface of the tongue. It shares several favorable characteristics with the buccal mucosa, making it a viable option for graft harvesting in reconstructive surgery. With grafts up to 7 or 8 cm long, the lingual mucosa can be a great substitute, particularly for patients who need bigger graft sizes or who have limited oral access due to a tiny mouth or difficulties opening their mouth widely. The sublingual mucosa harvesting procedure is simple, usually leaving only a hidden scar, and usually results in minimal oral discomfort after the procedure. Despite these benefits, SIMG is not as frequently utilized as BMG, perhaps because surgeons are less experienced with them and they are thinner.16

Labial mucosa graftThe mandibular labial mucosa is bordered by the vermillion border of the lower lip and the vestibular fold above and below, respectively, with lateral borders extending to the outer commissures. Its innervation comes from the mental nerve, a branch of the inferior alveolar nerve, which exits through the mental foramen between the first and second premolar teeth. To avoid nerve damage, incisions for labial mucosa harvest should be made medial to the canines. The area is vascularized by the inferior labial artery (from the facial artery), the mental artery (from the inferior alveolar artery), and anastomoses from the buccal artery. While labial mucosa is easy to harvest and requires no suturing, buccal mucosa is often preferred for larger, more robust grafts due to its greater width and quality.16

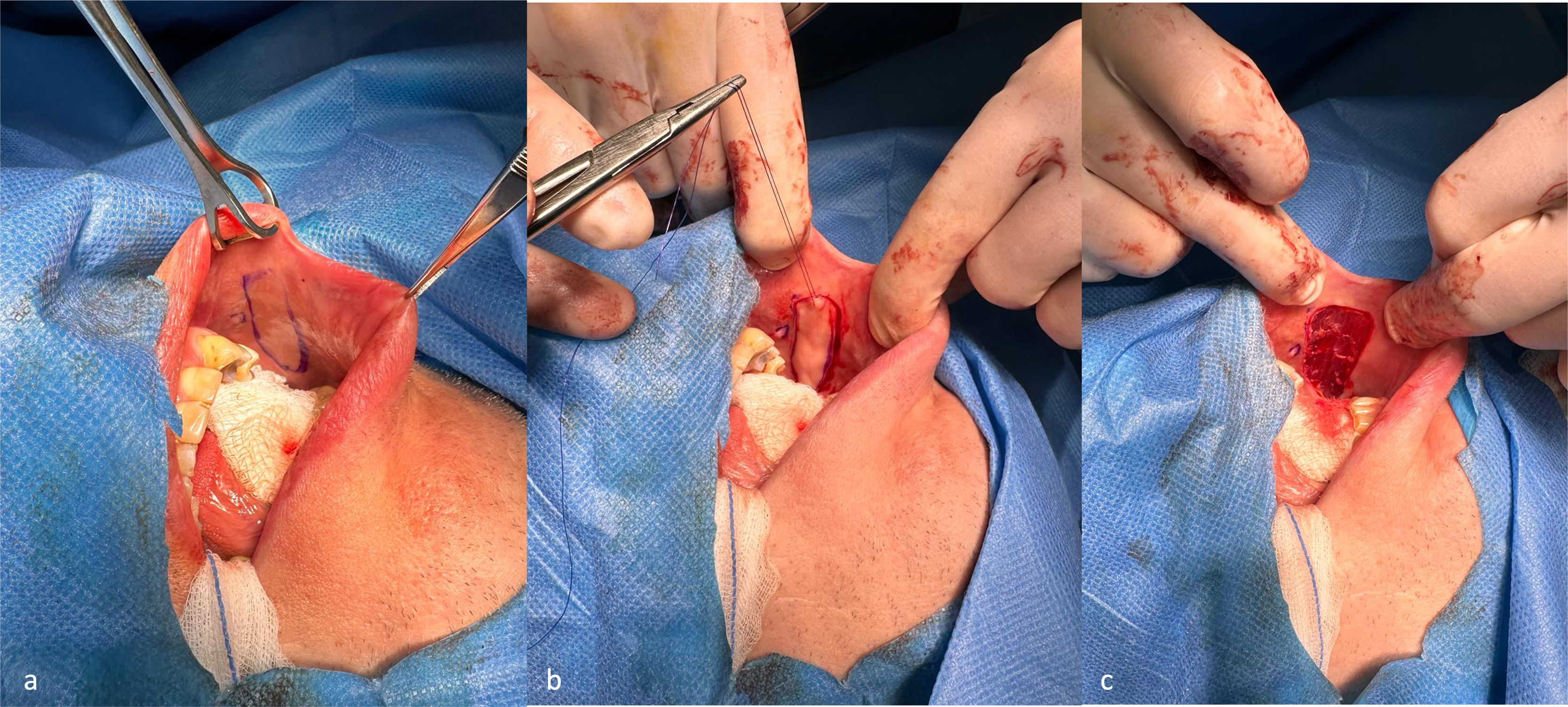

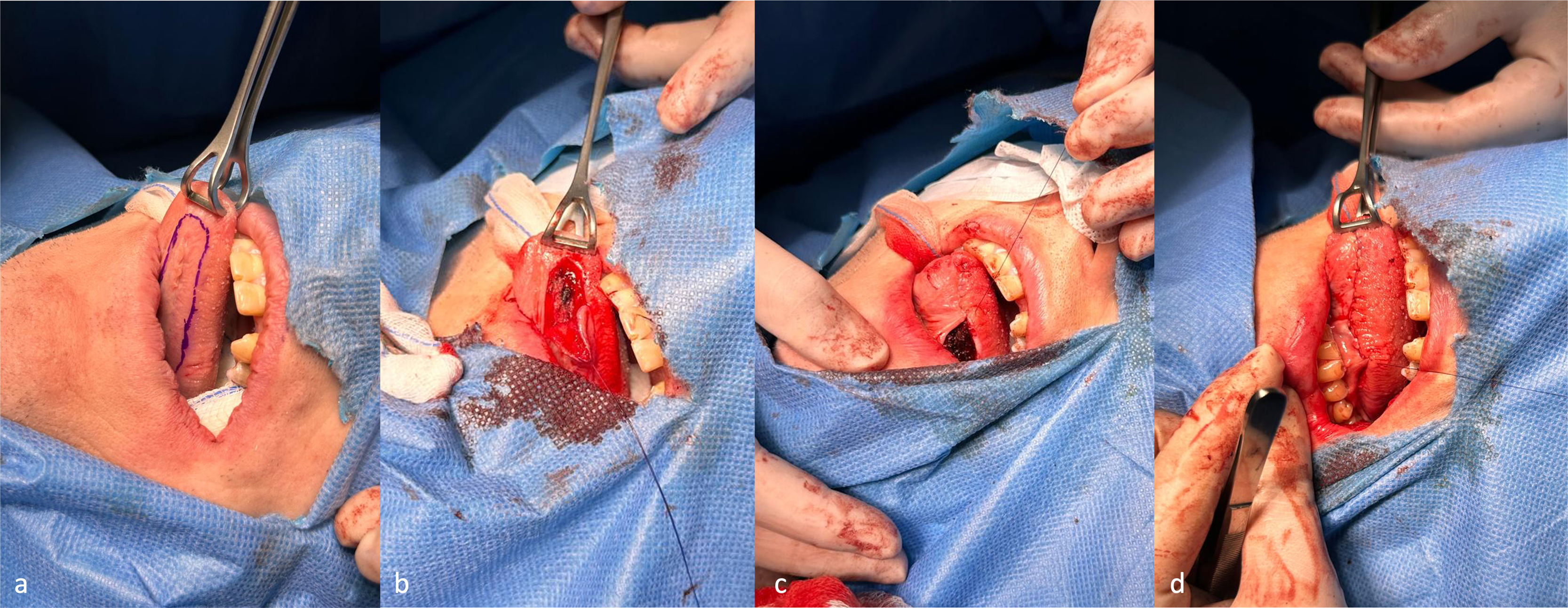

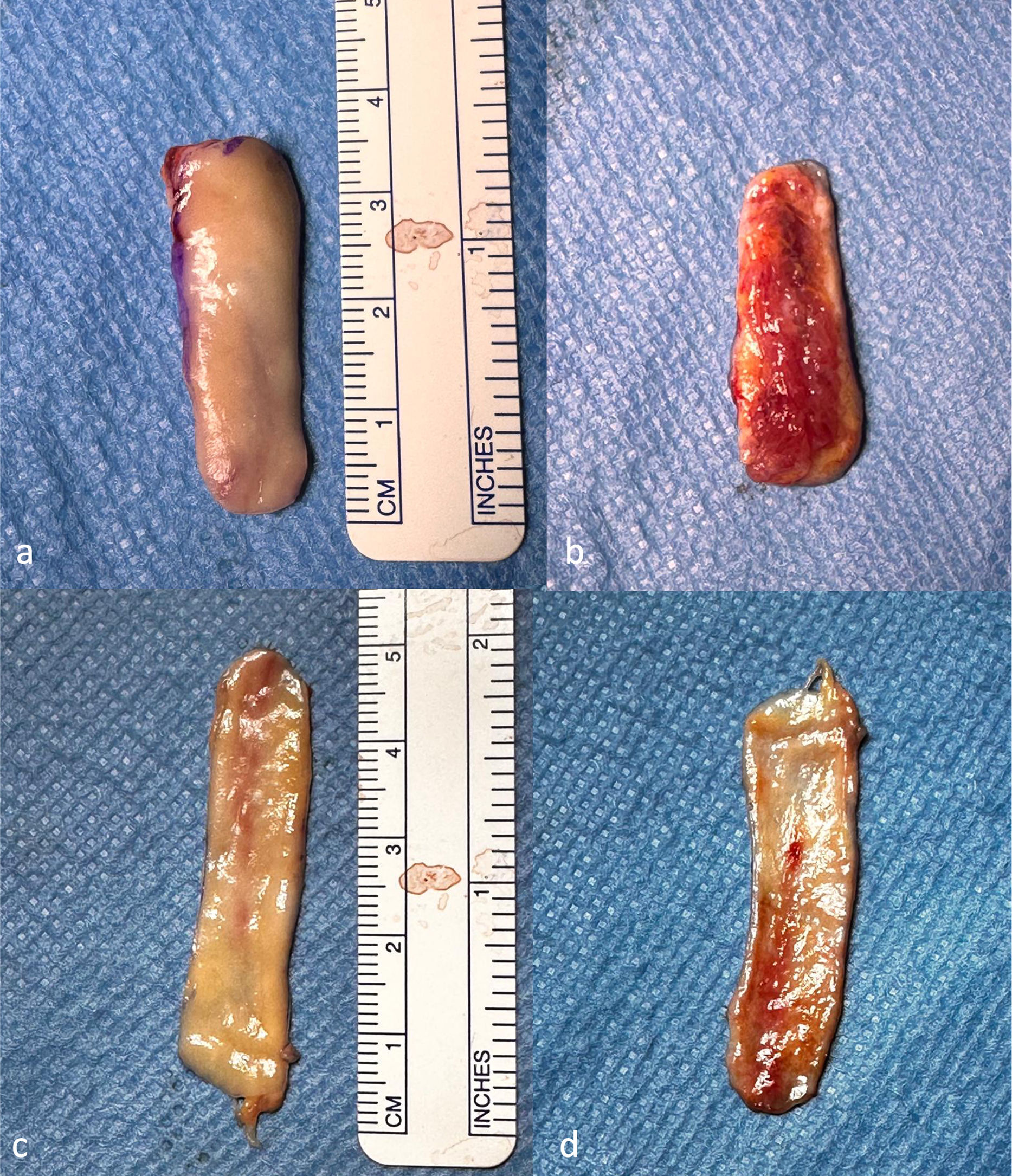

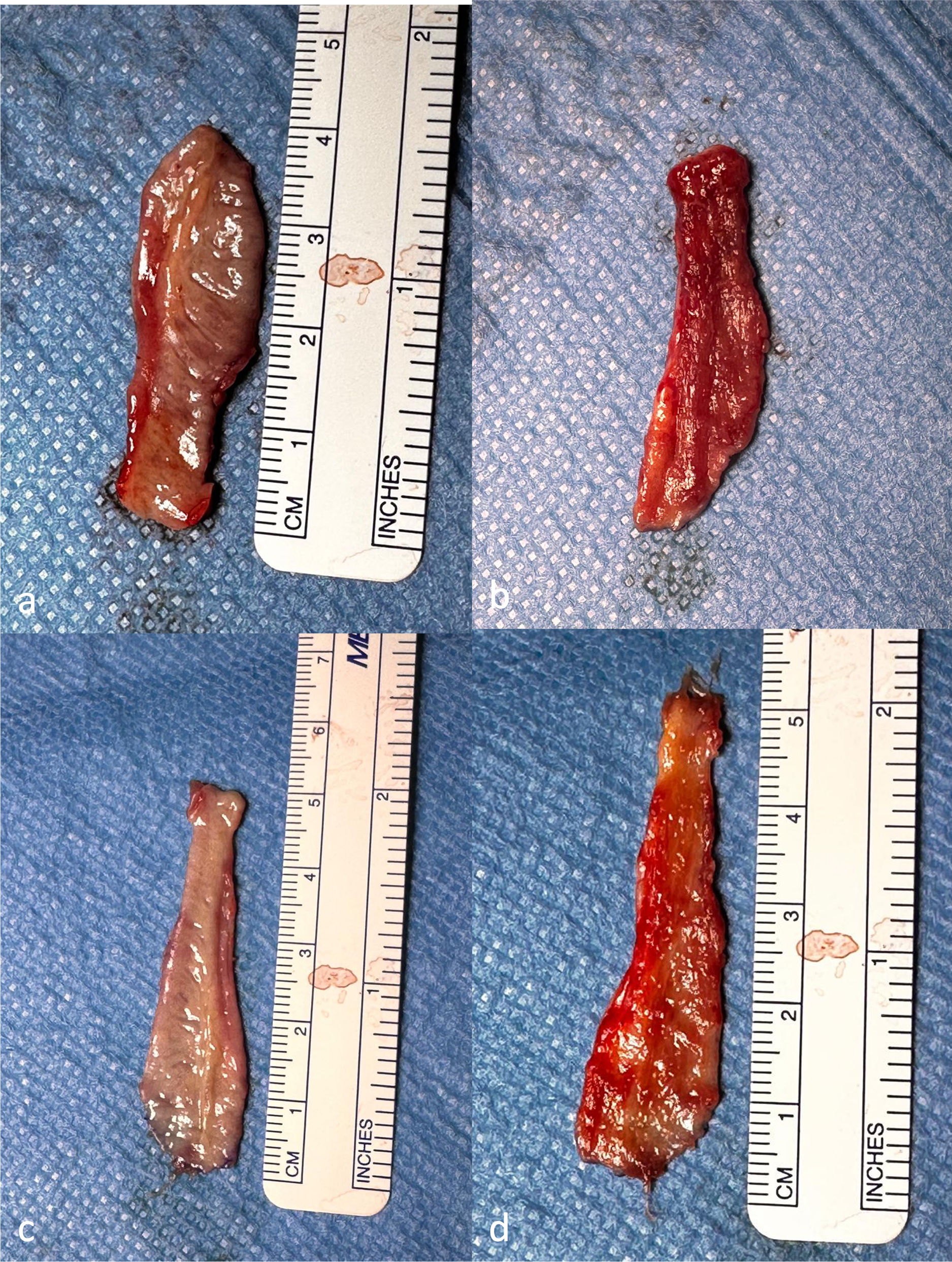

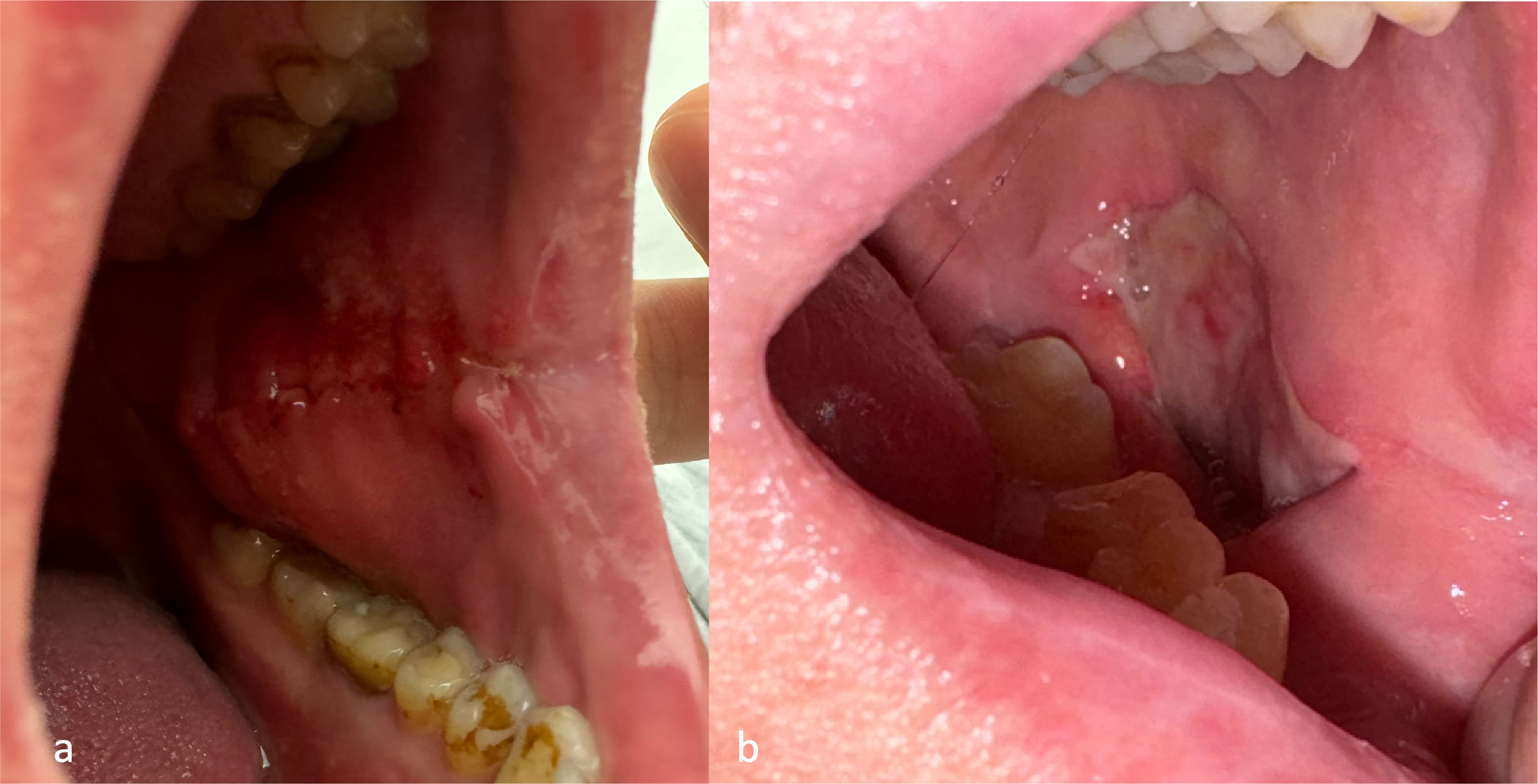

Graft preparationRegardless of the type of graft chosen, the surgical preparation is similar. The surgical field is prepared in a manner similar to that of maxillofacial surgery. Once the size of the graft needed has been determined (whether by preoperative examination or intraoperative measurement of defect length), the shape and dimensions of the graft are marked with a surgical pen (Fig. 3a, Fig. 4a) one must also take into account the fact that the graft may shrink by up to 20%.17 Particular care is required around the orifice of Stenson's duct when harvesting the BMG. A lignocaine and epinephrine solution is then administered submucosally, which helps elevate the tissue and has a hydrodissective effect. The stay suture is placed at the edge of the graft for better exposure. Mucosal incisions are then made in the areas previously marked, and then the graft is cut above the submucosal layer with scissors through sharp dissection (Fig. 3b, Fig. 4b). Bipolar diathermy may be used for hemostasis. The created graft is then processed on a side table. The surgeon gently removes the remnants of muscle tissue, salivary glands, and subcutaneous fatty tissue (Fig. 5, Fig. 6). After preparation, the graft is placed in a 0.9% NaCl solution and handed for implantation.

(a) Mucosal layer of the harvested BMG before removal of muscle tissue and fatty tissue. (b) Muscle layer of the harvested BMG before removal of muscle tissue and fatty tissue. (c) Mucosal layer of the harvested BMG after removal of muscle tissue and fatty tissue. (d) Muscle layer of the harvested BMG after removal of muscle tissue and fatty tissue.

(a) Mucosal layer of the harvested SIMG before removal of muscle tissue and fatty tissue. (b) Muscle layer of the harvested SIMG before removal of muscle tissue and fatty tissue. (c) Mucosal layer of the harvested SIMG after removal of muscle tissue and fatty tissue. (d) Muscle layer of the harvested SIMG after removal of muscle tissue and fatty tissue.

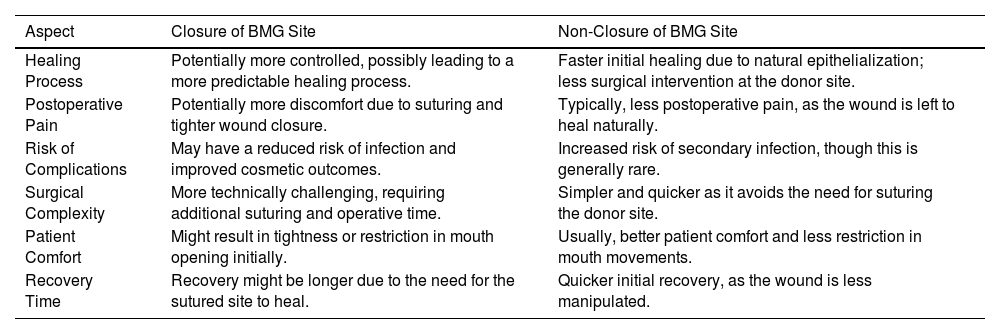

An important issue on which there is ongoing debate is the question of supplying the site of the harvest.18 Primary suturing offers potential benefits such as more effective control of bleeding and accelerated wound healing (Fig.7a). In contrast, secondary healing, where the wound is left open, is suggested to be preferable for alleviating oral pain and facilitating mouth opening difficulties (Fig.7b).19 The potential advantages and disadvantages of closure versus non-closure techniques after buccal mucosa graft harvesting are summarized in Table 1. In a recently published systematic review addressing the issue of postoperative oral morbidity, five randomized controlled trials with 346 patients who underwent unilateral BMG or SlMG harvest for augmentation urethroplasty with the harvest site non-closure or closure have been included.20 The results of this study indicate that the non-closure technique is characterized by lower postoperative pain, especially on postoperative day 1, with no significant difference in oral numbness, cosmetic defects, or the need for secondary oral procedures. It is worth noting, however, that the strength of the evidence was rated low or very low. Donor site complications after OMG harvesting are rare, affecting about 2% of patients undergoing OMG urethroplasty.21 However oral morbidity, especially in the first period after the surgery is an important factor influencing patients’ quality of life, leading to patient dissatisfaction with treatment in 15.6% of patients after BMG harvesting from one cheek and 31.7% after BMG harvesting from both cheeks in the early postoperative period.22

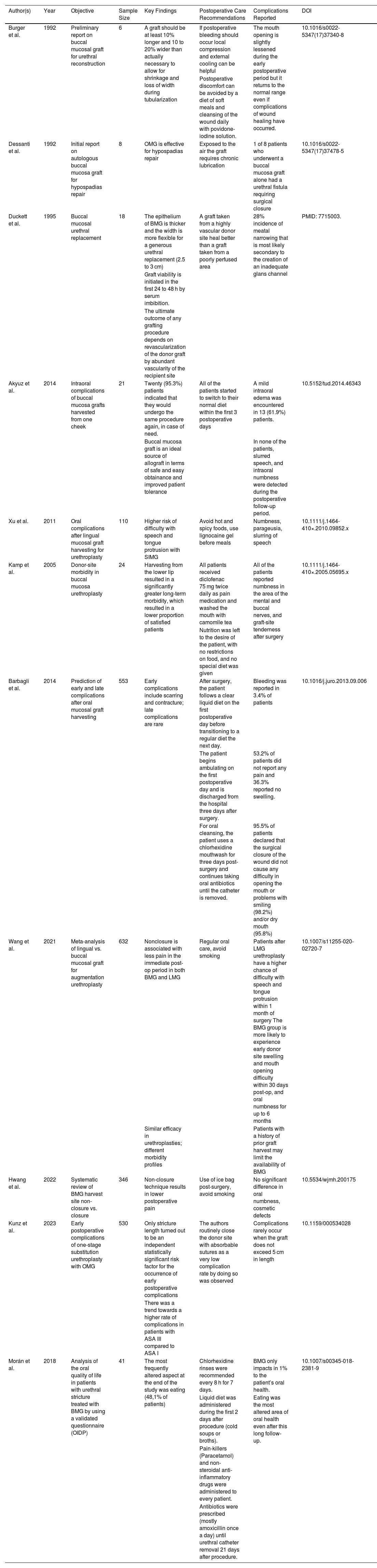

The potential advantages and disadvantages of closure versus non-closure techniques after buccal mucosa graft harvesting.

| Aspect | Closure of BMG Site | Non-Closure of BMG Site |

|---|---|---|

| Healing Process | Potentially more controlled, possibly leading to a more predictable healing process. | Faster initial healing due to natural epithelialization; less surgical intervention at the donor site. |

| Postoperative Pain | Potentially more discomfort due to suturing and tighter wound closure. | Typically, less postoperative pain, as the wound is left to heal naturally. |

| Risk of Complications | May have a reduced risk of infection and improved cosmetic outcomes. | Increased risk of secondary infection, though this is generally rare. |

| Surgical Complexity | More technically challenging, requiring additional suturing and operative time. | Simpler and quicker as it avoids the need for suturing the donor site. |

| Patient Comfort | Might result in tightness or restriction in mouth opening initially. | Usually, better patient comfort and less restriction in mouth movements. |

| Recovery Time | Recovery might be longer due to the need for the sutured site to heal. | Quicker initial recovery, as the wound is less manipulated. |

The most common donor site complications include scarring and contracture limiting jaw opening, paresthesia in the donor area, hematoma and dryness.18 Moreover, the anatomical complexity of the buccal region, encompassing salivary glands and the orifice of Stenson's duct, renders it susceptible to injuries during graft harvesting. Such injuries can lead to significant complications, such as sialadenitis or the formation of fistulas. Most of these complications resolve spontaneously in a period of up to 6 months. Long-term complications are common after SlMG harvesting. Twelve months after surgery, up to 13% still struggle with numbness, parageusia or slurring of speech, but these events overwhelmingly affect patients in whom the graft was taken on both sides of the sublingual region.23 The results of a meta-analysis evaluating studies comparing SlMG and BMG indicate that patients undergoing SlMG harvesting have a higher risk of difficulty with speech and tongue protrusion, and patients undergoing BMG harvesting are more likely to experience mouth opening difficulties and donor site swelling.12

There are several recommended practices for optimal oral care following OMG harvesting: wound care is crucial; dissection should maintain a minimum distance of 1 cm from the parotid duct opening, and suturing must be handled delicately if employed. Patients are advised to commence the use of chlorhexidine mouthwash twice daily for oral cleansing, starting the day before surgery, along with prophylactic antibiotics, aligned with local microbiological guidelines. Postoperatively, it is recommended to avoid hot and spicy foods. Some authors recommend applying lignocaine gel before meals as needed, and using chlorhexidine mouthwash and betadine gargles after meals for a week. Moreover, an ice bag may be applied to the cheek in the initial hours post-surgery to alleviate pain and prevent hematoma formation. In general, patients should refrain from smoking to reduce the risk of delayed wound healing and other complications.24

Smoking has a significant impact on the outcomes of BMG urethroplasty, particularly regarding stricture recurrence. Studies indicate that smoking acts as an independent risk factor for stricture recurrence post-urethroplasty. Specifically, the inflammatory response induced by smoking can exacerbate scar formation and impede wound healing. This is critical as successful urethroplasty relies heavily on proper healing of the grafted tissue. For patients undergoing BMG urethroplasty, the adverse effects of smoking on oral mucosa health further complicate the procedure. Chronic smoking can compromise the integrity and viability of the buccal mucosa used for grafting, increasing the likelihood of postoperative complications and stricture recurrence. Consequently, smoking cessation is highly recommended for patients before and after urethroplasty to enhance surgical outcomes and reduce the risk of recurrence.25Table 2 summarizes key findings from selected studies on buccal mucosa graft (BMG) in urethral reconstruction, including objectives, sample sizes, postoperative care recommendations, complications, and notable outcomes.

Summary of key points from selected studies.

| Author(s) | Year | Objective | Sample Size | Key Findings | Postoperative Care Recommendations | Complications Reported | DOI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Burger et al. | 1992 | Preliminary report on buccal mucosal graft for urethral reconstruction | 6 | A graft should be at least 10% longer and 10 to 20% wider than actually necessary to allow for shrinkage and loss of width during tubularization | If postoperative bleeding should occur local compression and external cooling can be helpful | The mouth opening is slightly lessened during the early postoperative period but it returns to the normal range even if complications of wound healing have occurred. | 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)37340-8 |

| Postoperative discomfort can be avoided by a diet of soft meals and cleansing of the wound daily with povidone-iodine solution. | |||||||

| Dessanti et al. | 1992 | Initial report on autologous buccal mucosa graft for hypospadias repair | 8 | OMG is effective for hypospadias repair | Exposed to the air the graft requires chronic lubrication | 1 of 8 patients who underwent a buccal mucosa graft alone had a urethral fistula requiring surgical closure | 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)37478-5 |

| Duckett et al. | 1995 | Buccal mucosal urethral replacement | 18 | The epithelium of BMG is thicker and the width is more flexible for a generous urethral replacement (2.5 to 3 cm) | A graft taken from a highly vascular donor site heal better than a graft taken from a poorly perfused area | 28% incidence of meatal narrowing that is most likely secondary to the creation of an inadequate glans channel | PMID: 7715003. |

| Graft viability is initiated in the first 24 to 48 h by serum imbibition. | |||||||

| The ultimate outcome of any grafting procedure depends on revascularization of the donor graft by abundant vascularity of the recipient site | |||||||

| Akyuz et al. | 2014 | Intraoral complications of buccal mucosa grafts harvested from one cheek | 21 | Twenty (95.3%) patients indicated that they would undergo the same procedure again, in case of need. | All of the patients started to switch to their normal diet within the first 3 postoperative days | A mild intraoral edema was encountered in 13 (61.9%) patients. | 10.5152/tud.2014.46343 |

| Buccal mucosa graft is an ideal source of allograft in terms of safe and easy obtainance and improved patient tolerance | In none of the patients, slurred speech, and intraoral numbness were detected during the postoperative follow-up period. | ||||||

| Xu et al. | 2011 | Oral complications after lingual mucosal graft harvesting for urethroplasty | 110 | Higher risk of difficulty with speech and tongue protrusion with SIMG | Avoid hot and spicy foods, use lignocaine gel before meals | Numbness, parageusia, slurring of speech | 10.1111/j.1464-410×.2010.09852.x |

| Kamp et al. | 2005 | Donor-site morbidity in buccal mucosa urethroplasty | 24 | Harvesting from the lower lip resulted in a significantly greater long-term morbidity, which resulted in a lower proportion of satisfied patients | All patients received diclofenac 75 mg twice daily as pain medication and washed the mouth with camomile tea | All of the patients reported numbness in the area of the mental and buccal nerves, and graft-site tenderness after surgery | 10.1111/j.1464-410×.2005.05695.x |

| Nutrition was left to the desire of the patient, with no restrictions on food, and no special diet was given | |||||||

| Barbagli et al. | 2014 | Prediction of early and late complications after oral mucosal graft harvesting | 553 | Early complications include scarring and contracture; late complications are rare | After surgery, the patient follows a clear liquid diet on the first postoperative day before transitioning to a regular diet the next day. | Bleeding was reported in 3.4% of patients | 10.1016/j.juro.2013.09.006 |

| The patient begins ambulating on the first postoperative day and is discharged from the hospital three days after surgery. | 53.2% of patients did not report any pain and 36.3% reported no swelling. | ||||||

| For oral cleansing, the patient uses a chlorhexidine mouthwash for three days post-surgery and continues taking oral antibiotics until the catheter is removed. | 95.5% of patients declared that the surgical closure of the wound did not cause any difficulty in opening the mouth or problems with smiling (98.2%) and/or dry mouth (95.8%) | ||||||

| Wang et al. | 2021 | Meta-analysis of lingual vs. buccal mucosal graft for augmentation urethroplasty | 632 | Nonclosure is associated with less pain in the immediate post-op period in both BMG and LMG | Regular oral care, avoid smoking | Patients after LMG urethroplasty have a higher chance of difficulty with speech and tongue protrusion within 1 month of surgery The BMG group is more likely to experience early donor site swelling and mouth opening difficulty within 30 days post-op, and oral numbness for up to 6 months | 10.1007/s11255-020-02720-7 |

| Similar efficacy in urethroplasties; different morbidity profiles | Patients with a history of prior graft harvest may limit the availability of BMG | ||||||

| Hwang et al. | 2022 | Systematic review of BMG harvest site non-closure vs. closure | 346 | Non-closure technique results in lower postoperative pain | Use of ice bag post-surgery, avoid smoking | No significant difference in oral numbness, cosmetic defects | 10.5534/wjmh.200175 |

| Kunz et al. | 2023 | Early postoperative complications of one-stage substitution urethroplasty with OMG | 530 | Only stricture length turned out to be an independent statistically significant risk factor for the occurrence of early postoperative complications | The authors routinely close the donor site with absorbable sutures as a very low complication rate by doing so was observed | Complications rarely occur when the graft does not exceed 5 cm in length | 10.1159/000534028 |

| There was a trend towards a higher rate of complications in patients with ASA III compared to ASA I | |||||||

| Morán et al. | 2018 | Analysis of the oral quality of life in patients with urethral stricture treated with BMG by using a validated questionnaire (OIDP) | 41 | The most frequently altered aspect at the end of the study was eating (48,1% of patients) | Chlorhexidine rinses were recommended every 8 h for 7 days. | BMG only impacts in 1% to the patient’s oral health. | 10.1007/s00345-018-2381-9 |

| Liquid diet was administered during the first 2 days after procedure (cold soups or broths). | Eating was the most altered area of oral health even after this long follow-up. | ||||||

| Pain-killers (Paracetamol) and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs were administered to every patient. | |||||||

| Antibiotics were prescribed (mostly amoxicillin once a day) until urethral catheter removal 21 days after procedure. |

In the long-term management of complications following OMG urethroplasty, it's crucial to address the possibility of quality-of-life deterioration regarding the site of the graft harvest. Although there are no large randomized studies on this topic, the publication by Morán et al. provides good quality data. The authors reveal minimal statistically significant deterioration over a three-year follow-up period indicating that while common complications such as mild trismus and changes in chewing efficiency persist, they do not significantly impact the overall oral health-related quality of life. The management strategy primarily involves routine oral hygiene and diet modifications immediately post-surgery, supplemented with pain management through standard analgesics and antibiotics to prevent infection. Proactive oral care, including the use of chlorhexidine rinses and careful monitoring of dietary intake, plays a vital role in minimizing these complications. Morán et al. used a validated questionnaire OIDP (Oral Impacts on Daily Performances) to systematically assess the impact on daily activities, highlighting that eating is the most affected domain. This study was the first to assess oral health quality of life using a validated questionnaire; unfortunately, this meant that the findings could not be compared with previous literature. Despite these challenges, data show that overall patient satisfaction remains high, underscoring the importance of tailored follow-up care to manage and minimize postoperative oral complications effectively.26

Future directionsFurther research is essential to enhance oral care pathways following OMG harvesting. There is a significant need to study long-term oral morbidity. While immediate postoperative care is well-documented, long-term follow-up studies are crucial to understanding the chronic impact of OMG harvesting on oral functions such as sensation, taste, and mobility. Additionally, there is a lack of standardized, evidence-based oral care protocols following OMG harvesting. Future studies should aim to develop and validate protocols that minimize complications and enhance recovery. These protocols should focus on pain management, infection prevention, and the promotion of mucosal healing. Patient-reported outcomes are also underrepresented in current research. More studies using patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) are needed to understand the patient's perspective, including their satisfaction with the surgical outcome and the impact on daily life activities such as eating and speaking. Moreover, comparative studies on the morbidity and functional outcomes of different graft harvesting sites (buccal, labial, and lingual mucosa) are needed. This will help understand which sites offer the best balance between graft quality and donor site morbidity. Finally, the role of emerging technologies like tissue engineering, regenerative medicine, and growth factors in improving graft take and minimizing donor site morbidity should be investigated. This could lead to significant improvements in patient outcomes.

Research limitationsA major limitation of the studies included in the analysis is the short follow-up of patients after BMG graft harvesting. Thus, the review is limited by the inability to assess the long-term outcomes of the interventions. Moreover, the studies included in the search results were limited by the small sample sizes, methodological diversity, and inconsistencies in reported outcomes among published studies. Another limitation of the studies included in the analysis is that most of them did not account for or adjust the outcomes based on the etiology of the urethral stricture, which could potentially influence the success rates and complications of OMG urethroplasty. For example, patients with lichen sclerosus (LS) pose a major therapeutic challenge due to higher risks of complications and surgical treatment failure. Despite the fact that patients with LS are a rare group of USD etiology and account for less than 4% of patients, these strictures are longer on average and OMG grafts are often inevitable. Therefore, further high-quality studies with adequate sample sizes and longer follow-up durations are needed to further assess, validate, and improve the evidence on the morbidity of BMG harvest sites on post-operative oral pain and other patient-reported oral morbidities related to BMG harvest site management.27

ConclusionEffective management in reconstructive urology extends beyond the surgery itself, underlining the importance of optimizing graft harvesting techniques. The choice of graft site— buccal, labial, or lingual mucosa— affects surgical outcomes and patient recovery. Buccal mucosa grafts are preferred for their robustness, while sublingual and labial grafts are chosen based on specific patient needs and anatomies. Management of harvest site morbidity includes decisions on closure techniques. Opting for non-closure typically results in less postoperative pain and quicker healing, but the approach must be tailored to individual patient needs to minimize risks such as infection or delayed healing. Postoperative care includes oral hygiene, pain management, and dietary adjustments to support healing and reduce discomfort. Long-term follow-up indicates that complications like mild trismus and changes in chewing efficiency are common but have minimal impact on overall quality of life. This underscores the importance of ongoing monitoring and patient education to effectively manage and minimize postoperative complications. In conclusion, adopting a holistic, patient-centered approach to perioperative care following OMG harvesting is essential for achieving optimal outcomes. By integrating current best practices and promoting further research, the field can continue to advance, improving patient experiences and outcomes after these complex reconstructive procedures. Comparative studies on different graft sites and the integration of patient-reported outcomes will enrich our understanding and improve care pathways for patients undergoing OMG harvesting, ultimately leading to better surgical outcomes and enhanced quality of life.