The aetiology of chronic urticaria is usually considered idiopathic. There is a paucity of research both on the prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection in the aetiology of chronic spontaneous urticaria (CU) in children and also on which patients H. pylori should be investigated.

MethodsAll paediatric and adult patients who presented to the allergy outpatient clinic due to CU between January 2011 and July 2012 were included in this prospective, randomised study. Stool samples from all patients were examined for the H. pylori antigen. Paediatric and adult patients who had a positive stool test for the H. pylori antigen were reassessed following eradication therapy.

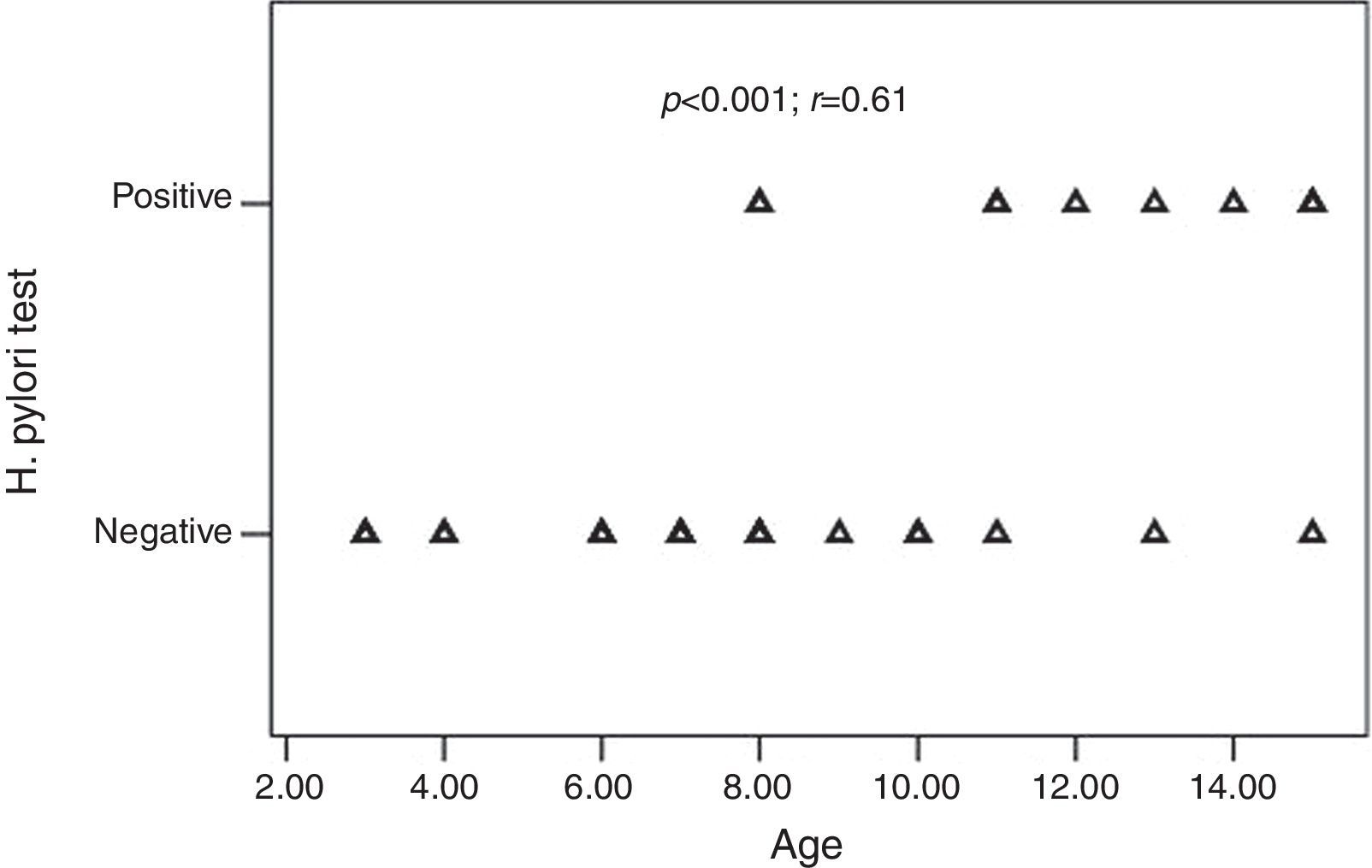

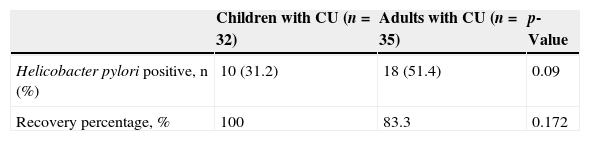

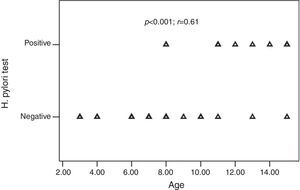

ResultsThirty-two children with CU and 35 adults with CU were enrolled in the study. Ten of the 32 (31.2%) children and 18 of the 35 (51.4%) adults were H. pylori positive (p=0.09). All children with positive-H. pylori were older than eight years of age. There was a significant positive correlation between age and the frequency of H. pylori infection (p<0.001; r=0.61). The presence of H. pylori was not significantly associated with the presence of GI (gastrointestinal) symptoms (p>0.05). Following H. pylori eradication, urticarial symptoms recovered in 15 of the adults (83.3%) and 10 of the paediatric (100%) patients (p=0.172).

ConclusionIn the current study we found that H. pylori is common among children with CU, particularly after eight years of age. We suggest that CU patients with an unknown aetiology should be routinely screened for H. pylori even if they do not present with GI symptoms and that those with H. pylori-positive results may receive treatment.

Urticaria is defined as transient, pruritic, variably sized wheals with central pallor and well-defined borders. Urticaria has historically been classified as either acute or chronic based on its duration (acute, lasting fewer than six weeks, and chronic, lasting six or more weeks).1 While up to 25% of adults are estimated to experience at least one episode of acute urticaria at some time in their lifetime, only around 3% will develop chronic spontaneous urticaria (CU).2 The prevalence of CU is reported to be around 0.6% in adults.3 In children, however, urticaria seems to be less common and the incidence of overall childhood urticaria of any form is reported to be around 3.4–5.4%. In the United Kingdom chronic urticaria has been reported to affect 0.1–0.3% of all children.4

The aetiology of chronic urticaria is usually considered idiopathic. The rate of children with identified aetiology varies widely, and is reported to be between 21% and 51% 4. The role of infections in chronic urticaria is well recognised.5 Data regarding Helicobacter pylori infection have primarily been collected from studies conducted on adult chronic urticaria patients. In a recent study, H. pylori infection was identified in 22.9% of adult chronic urticaria patients.6 Studies about the prevalence of H. pylori infection among paediatric patients with chronic urticaria, however, are lacking. Current guidelines recommend performing routine blood count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C reactive protein testing when screening for CU aetiology and also additional extended parameters including H. pylori in patients with clinical suspicion. However, these guidelines do not exactly describe the criteria for clinical suspicion of H. pylori, hence leaving a gap of knowledge for the potential patients to be screened for H. pylori in the aetiology of CU.7

In this study, we aimed to determine the risk factors of H. pylori infection and H. pylori treatment response in children with CU. We also aimed to determine the prevalence of H. pylori infection among children presenting to the paediatric and adult allergy clinics within a given time period and to compare it with the prevalence in the adult population.

Materials and methodsStudy subjectsAll patients who presented to the paediatric and adult allergy outpatient clinics of Fatih University due to CU between January 2011 and July 2012 were included in this prospective, randomised study. For each children with CU included in the study, we enrolled an adult with CU. Overall 37 children and adults with CU were enrolled. Because five children and two adults did not complete their treatment, they were excluded from the study, leaving 32 children and 35 adults with CU. CU was defined based on the current guideline as urticarial symptoms lasting for six or more weeks.7 Patients who had any infectious agent (except for H. pylori), were excluded from the study. During the study period all adult and paediatric patients with CU were screened for H. pylori from stool samples. Self and family history of allergic diseases, the presence of parental consanguinity and gastrointestinal (GI) complaints (epigastric pain, nausea, regurgitation, abdominal distension, etc.) were recorded in paediatric patients. Additionally, extensive aetiological investigations were planned for paediatric patients. Both paediatric and adult patients with a positive stool test for H. pylori antigen received eradication therapy [lansoprazole capsules (paediatric dosage 15–30mg/day; adult dosage 30mg bid) for 1 month, amoxicillin (paediatric dosage 50mg/kg/day bid; adult dosage 1g bid) and 15mg/kg/day clarithromycin (paediatric dosage 15mg/kg/day bid; adult dosage 500mg bid) for 15 days]. All children and adult with CU received oral daily antihistamines (5mg/day cetirizine or 2.5–5mg/day desloratadine) for one month. Of these, 11 (4 children and 7 adults) were started on daily oral systemic corticosteroids due to exacerbation of symptoms and were followed by careful dose titration for 3–7 days. Four weeks after the completion of eradication therapy, patients were recalled for control examinations. They were inquired for complaints and retested for H. pylori antigen. Remission was defined as being free of symptoms such as wheals and pruritus although not receiving any medical treatment for a minimum of seven consecutive days.7

Venous blood samples were collected into Vacuette tubes (Greiner Bio-One, Monroe, NC, USA) and centrifuged at 3000×g for 15min at 4°C. Complete blood count analysis was performed with the LH-780 system (Beckman Coulter Diagnostics, Image 8000, Brea, CA, USA). C reactive protein (CRP) levels were measured by turbidimetric assay method using a Roche P 800 modular system (Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan). Levels of total serum IgE were measured by the ECLIA (electrochemiluminescence immunoassay) method using an ELX-800 system (DIAsource, Nivelles, Belgium). ANA and anti-dsDNA were determined by means of indirect immunofluorescence testing (Euroimmune, Lübeck, Germany). C3 and C4 levels were determined by immunonephelometry (Beckman Coulter Diagnostics, Immage 8000, Brea, CA, USA). Thyroglobulin (Tg, Anti-T) and thyroid peroxidase (TPO, Anti-M) autoantibodies were detected by chemiluminescence immunoassays using the IMMULITE 2000 system (Roche Diagnostics, Integra 800, Mannheim, Germany). H. pylori infection was assessed using Hp Rapid Strip Test, based on a lateral flow chromatography with polyclonal antibodies (ACON Laboratories Inc, San Diego, CA, USA).

Atopy in the patients was assessed using a skin prick test (SPT) and specific IgE (sIgE) measurements. We defined a positive SPT test as a wheal with a mean diameter of at least 3mm greater than that of a saline control. Each child was tested with a core battery of allergens (e.g. dust mite, cockroach, cat, dog, mould, grass, tree, weed, milk, egg, peanut) and a clinic-specific battery of locally relevant allergens (ALK Abelló, Hørsholm, Denmark).

Statistical analysisStatistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPPS) for Windows, version 16.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, United States). We expressed categorical variables as percentages and continuous variables as mean±standard deviation (SD). We used the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test to evaluate whether the distribution of continuous variables was normal. The Chi-square test was used to analyse categorical variables and bivariate (Pearson) correlation analyses to assess the correlation between independent parameters. A p value<0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

This study protocol was approved by the ethical committee of Fatih University. Written informed consent was obtained from all adult patients and from the parents of the children.

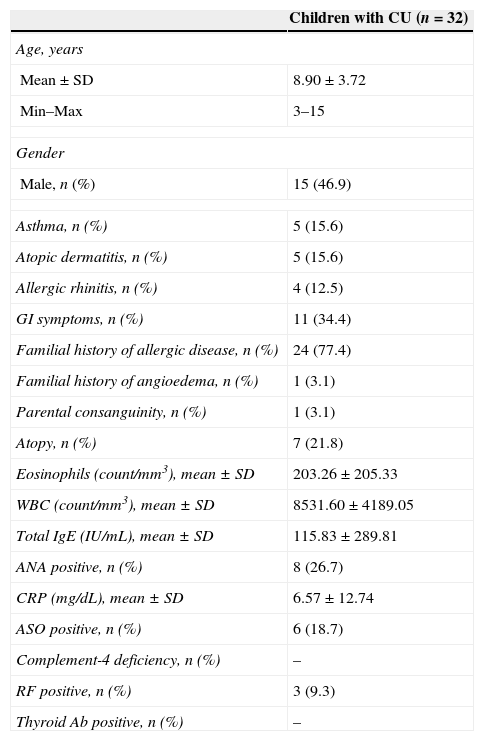

ResultsThirty-two children with CU (17 females, 15 males; mean age: 8.90±3.72 years; range: 3–15 years) and 35 adults with CU (22 females, 13 males; mean age: 41.71±14.81 years; range: 21–80 years) were enrolled in the study. The demographic characteristics of children with CU are presented in Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of children with chronic spontaneous urticaria.

| Children with CU (n=32) | |

|---|---|

| Age, years | |

| Mean±SD | 8.90±3.72 |

| Min–Max | 3–15 |

| Gender | |

| Male, n (%) | 15 (46.9) |

| Asthma, n (%) | 5 (15.6) |

| Atopic dermatitis, n (%) | 5 (15.6) |

| Allergic rhinitis, n (%) | 4 (12.5) |

| GI symptoms, n (%) | 11 (34.4) |

| Familial history of allergic disease, n (%) | 24 (77.4) |

| Familial history of angioedema, n (%) | 1 (3.1) |

| Parental consanguinity, n (%) | 1 (3.1) |

| Atopy, n (%) | 7 (21.8) |

| Eosinophils (count/mm3), mean±SD | 203.26±205.33 |

| WBC (count/mm3), mean±SD | 8531.60±4189.05 |

| Total IgE (IU/mL), mean±SD | 115.83±289.81 |

| ANA positive, n (%) | 8 (26.7) |

| CRP (mg/dL), mean±SD | 6.57±12.74 |

| ASO positive, n (%) | 6 (18.7) |

| Complement-4 deficiency, n (%) | – |

| RF positive, n (%) | 3 (9.3) |

| Thyroid Ab positive, n (%) | – |

Ab, antibody; ANA, antinuclear antibody; ASO, antistreptolysin O; CRP, C reactive protein; CU, chronic spontaneous urticaria; GI, gastrointestinal; IgE, immunoglobulin E; WBC, white blood cells.

H. pylori was positive in 10 of the 32 (31.2%) children and 18 of the 35 (51.4%) adults with CU. The frequency of H. pylori was statistically similar between the groups (p=0.09) (Table 2). All children with positive-H. pylori were older than eight years of age. Older children had significantly higher rates of H. pylori infection than the younger ones. There was a significant positive correlation between age and the frequency of H. pylori infection (p<0.001; r=0.61) (Fig. 1).

Comparison of H. pylori prevalence and treatment response in paediatric and adult chronic spontaneous urticaria patients.

| Children with CU (n=32) | Adults with CU (n=35) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Helicobacter pylori positive, n (%) | 10 (31.2) | 18 (51.4) | 0.09 |

| Recovery percentage, % | 100 | 83.3 | 0.172 |

CU: chronic spontaneous urticaria.

Chi-square test.

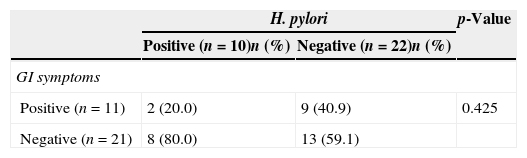

Of the H. pylori-positive 10 children, eight (80%) did not present with any GI symptoms and only two (18.1%) of the patients with positive GI symptoms were found to be H. pylori-positive (Table 3). As a result, no significant correlation was detected between the presence of GI symptoms and H. pylori (p>0.05). Both paediatric and adult patients with a positive stool test for the H. pylori antigen received eradication therapy (lansoprazole for one month, amoxicillin and clarithromycin for 15 days). Four weeks after the completion of eradication therapy, the patients were recalled for control examinations. They were inquired for complaints and retested for the presence of H. pylori antigen. Control stool samples of all paediatric and adult patients proved negative. Fifteen of the adult (83.3%) and 10 of the paediatric (100%) patients fully recovered from urticarial symptoms following H. pylori eradication therapy (p=0.172) (Table 3).

Association between H. pylori and GI symptoms in paediatric chronic spontaneous urticaria patients.

| H. pylori | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive (n=10)n (%) | Negative (n=22)n (%) | ||

| GI symptoms | |||

| Positive (n=11) | 2 (20.0) | 9 (40.9) | 0.425 |

| Negative (n=21) | 8 (80.0) | 13 (59.1) | |

CU: chronic spontaneous urticaria; GI: gastrointestinal.

Chi-square test.

The role of H. pylori infection in the pathogenesis of CU is still controversial. Except for H. pylori the following chronic persistent bacterial, viral, parasitic and fungal agents have been previously cited in the aetiology of CU: streptococci, staphylococci, Yersinia, Giardia lamblia, Mycoplasma pneumonia, hepatitis virus, norovirus, parvovirus B19, Anisakis simplex, Entamoeba spp., and Blastocystis spp. have been suspected to trigger urticarial symptoms in patients with CU.7 Although some authors report a lack of association between H. pylori eradication and remission of CU,8,9 other authors describe a beneficial role of H. pylori eradication therapy on CU.10 Current guidelines on the management of CU state that the treatment of associated infectious and/or inflammatory conditions, including H. pylori dependent gastritis, may be helpful in selected cases.11

In the current study, a substantial number of paediatric patients (31.2%) with CU, all of whom were older than eight years, were positive for H. pylori antigen. Most significantly, the majority of these patients (80%) did not complain of any GI symptoms. We detected H. pylori in 51.4% of adult CU patients. The prevalence of H. pylori between adult and paediatric patients was statistically similar. The main results of this study may be summarised as follows: (1) H. pylori infection is not a rare condition in children with CU; (2) 80% of the H. pylori-positive patients did not present with GI symptoms; (3) our results imply that the presence of GI symptoms should not be considered as a prerequisite for H. pylori screening; (4) because H. pylori was not identified in children younger than eight years of age, routine H. pylori assessment may rather be performed in children older than eight years; and (5) H. pylori-positive patients responded well to the eradication therapy.

There is still a paucity of data in the literature about the physiopathology, aetiology and treatment of childhood CU. A substantial amount of our knowledge with regard to CU relies on our experience obtained from adult patients. CU is usually considered idiopathic, and data pertaining to the aetiology and treatment of the disease are limited in the literature.4 Identifying any of the potential causes of CU will evidently increase the likelihood of effective cure; hence we believe that patients receiving eradication therapy for H. pylori should be closely followed to ensure successful cure.

Depending on geographical and population variance, H. pylori may also be identified in healthy individuals. The frequency of H. pylori infection among children is reported to be around 65% in Turkey. Our findings are in accordance with previous studies which reported a proportional increase in the prevalence of H. pylori with age, particularly in children older than 10 years.12,13. Although the association of H. pylori and CU is still controversial,9 current guidelines state that the eradication of H. pylori may be beneficial in selected cases.11 Indeed, the quality of life of some patients with CU who previously failed treatment with standard strategies has been observed to improve following H. pylori eradication.

Our study has several limitations. These may be summarised as the limited number of patients, the lack of a control group, and the fact that GI complaints were not endoscopically confirmed. However, the comparison of adult and paediatric patients with regard to H. pylori prevalence throughout the 18-month study period provides an overall insight. Spontaneous recovery from CU has been previously reported; hence the lack of a non-treated control group with H. pylori positive patients is a limiting factor. Nevertheless, the positive response rates following eradication therapy supports the need for H. pylori infection treatment. As to the method of choice for diagnosis, although endoscopic methods are the gold standards, they are invasive and current guidelines state that the examination of H. pylori antigen from stool samples is an effective and reliable non-invasive diagnostic alternative method.14–16

As a conclusion, the prevalence of H. pylori in children with CU is high, particularly after eight years of age. Therefore we suggest that routine H. pylori investigation would be beneficial for CU patients with an unknown aetiology even if they present with no GI symptoms. The non-invasive screening of H. pylori in paediatric CU patients may easily be performed through stool samples.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this investigation.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work centre on the publication of patient data and that all the patients included in the study have received sufficient information and have given their informed consent in writing to participate in that study.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained the informed consent of the patients and/or subjects mentioned in the article. The author for correspondence is in possession of this document.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflict of interest to declare.