Allergy to beta-lactam (βL) antibiotics is highly reported in children, but rarely confirmed. Risk factors for a positive diagnostic work-up are scarce.

The primary aim was to characterize the cases of children with confirmed βL allergy, investigating potential risk factors. Secondary aims were to assess the prevalence of allergy to βL in this population and to confirm the safety of less extensive diagnostic protocols for milder reactions.

MethodsWe reviewed the clinical data from all children evaluated in our Department for suspected βL allergy, over a six-year period.

ResultsTwo hundred and twenty children (53% females) with a mean age of 6.5±4.2 years were evaluated. Cutaneous manifestations were the most frequently reported (96.9%), mainly maculopapular exanthema (MPE). The reactions were non-immediate in 59.5% of the cases.

Only 23 children (10.5%) were diagnosed with allergy to βL. The likelihood of βL allergy was significantly higher in children with a family history of drug allergy (p<0.001) and in those with a smaller time period between the reaction and the study (p=0.046). The probability of not confirming βL allergy is greater in children reporting less severe reactions (p<0.001) and MPE (p<0.001).

We found the less extensive diagnostic protocol in milder reactions safe, since only 4.2% of the children presented a positive provocation test (similar reaction as the index reaction).

ConclusionThis study highlights family history of drug allergy as a risk factor for a positive diagnostic work-up. Larger series are required, particularly genetic studies to accurately determine future risk for βL allergy in children.

Beta-lactam (βL) antibiotics are the most commonly prescribed drugs in children1,2 and also the most frequently implicated in drug allergy in these age groups.3–6 Despite high suspicion rates and reports, only between 3.9% and 15.9% of the cases are confirmed by an allergy diagnostic work-up.1,7–12

These procedures are mandatory to define safe alternatives in the cases of confirmed allergy, but also to rule out the negative ones and prevent the negative impact of antibiotic allergy labels on clinical outcomes in children.2,6,13

There is no general consensus regarding the diagnostic protocols in paediatric ages and this topic is being highly debated. Moreover, studies on risk factors for a positive diagnostic work-up are scarce.

The primary aim of this study was to characterize the confirmed cases of βL allergy in children, investigating potential risk factors. Secondary aims were to assess the prevalence of allergy to this drug class in the studied population and to confirm the safety of less extensive diagnostic protocols for milder reactions.

Material and methodsPatientsWe retrospectively reviewed the clinical data from all children (younger than 18 years) assessed in our Allergy and Clinical Immunology Department for suspected βL allergy over a six-year period (January 2012 to December 2018).

Patients that did not complete the drug allergy diagnostic work-up were excluded.

Drug allergy work-upFor diagnostic purposes and in agreement with international guidelines, reactions were classified as immediate and non-immediate according to the time between drug intake and the onset of clinical symptoms.14 In cases of multiple reactions (to single or multiple βL), the most severe reaction was considered.

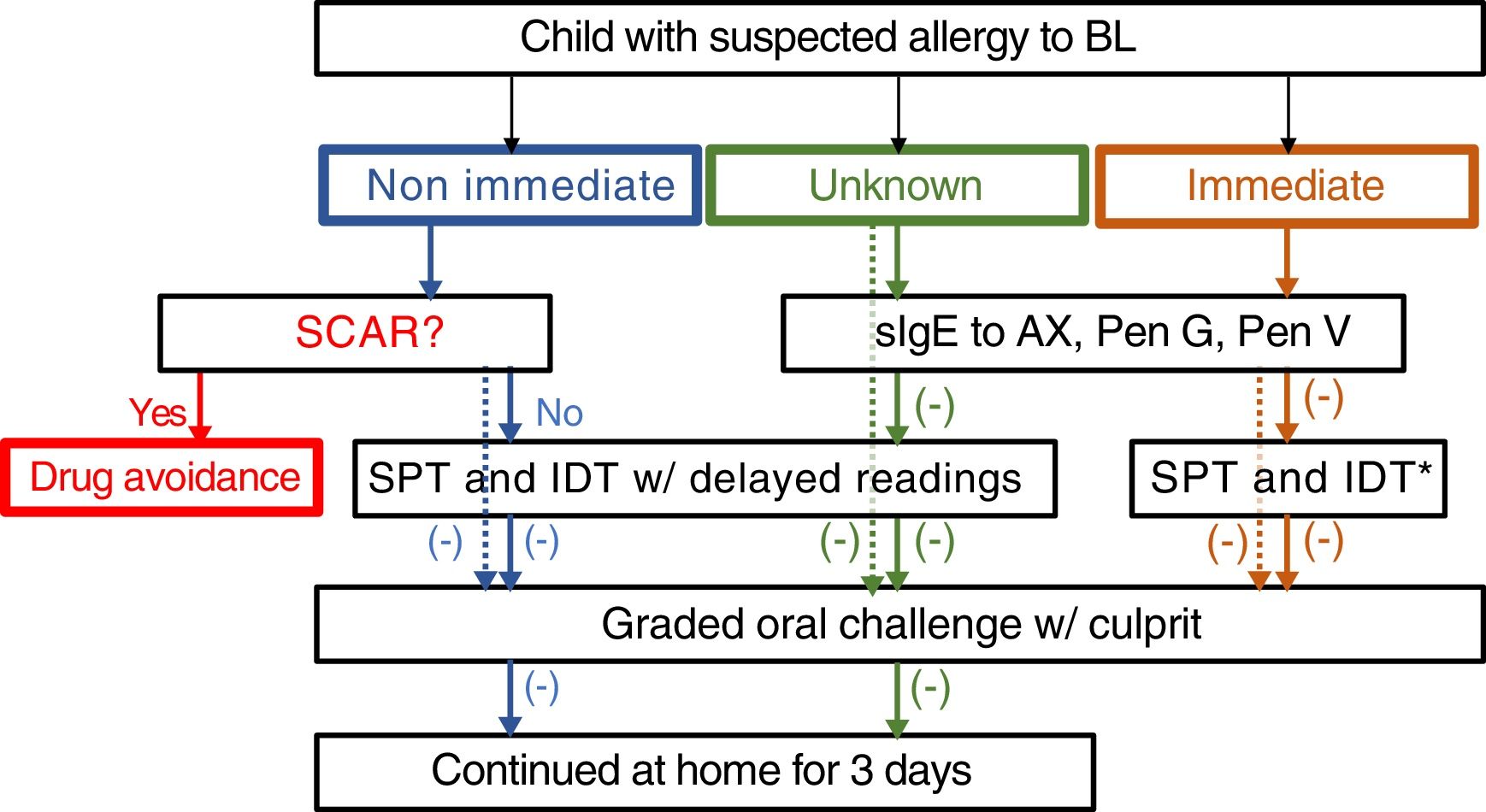

The drug allergy work-up included a validated questionnaire15 and, depending on the reaction type and severity, skin tests, specific IgE and/or drug provocation test (Fig. 1). All the diagnostic procedures followed the ENDA/EAACI (European Network of Drug Allergy/European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology) recommendations16–19 and were performed by trained specialists, in a day-care hospital under strict surveillance.

Algorithm for management suspected allergy to beta lactam antibiotics in children. In the case of positive sIgE skin test to the culprit drug, study is continued to confirm tolerance to a reasonable alternative (e.g. 3rd generation cephalosporins if allergic to aminopenicillins). Dotted lines: mild drug reaction. *Readings at 20min only. HSR: hypersensitivity reaction; BL: betalactam antibiotics; sIgE: specific IgE, AX: amoxicillin; Pen: penicilloyl; IDT: intradermal tests; SPT: skin prick tests.

Serum-specific IgE antibodies (sIgE) (ImmunoCAP®, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Uppsala, Sweden) for penicillin G/V and amoxicillin were used, when evaluating immediate reactions or those with unknown time of occurrence. A cut-off value of ≥0.35kU/L was considered positive.19

Skin prick tests (SPT) were performed and if negative, intradermal tests (IDT) with benzylpenicilloyl octa-l-lysine (PPL), sodium benzylpenilloate – minor determinant (MDM) (DAP® Penicillin, Diater, Madrid, Spain), penicillin G (PenG), amoxicillin/clavulanic acid (AX/CL) and ceftriaxone16,17,19 were also performed. Other βL were tested according to the suspected drug. Late readings (after 48h) were done in the cases of non-immediate reactions or those with unclear time of occurrence.

Given the low sensitivity of patch tests in the diagnosis of delayed reactions to βL,17 they were not carried out routinely in all the cases of non-immediate reactions.

DPT with culprit drug were performed whenever skin tests and sIgE were negative and in the absence of other contraindications.18,19 In children with mild reactions DPT was performed with the culprit drug without previous skin testing. In non-immediate reactions or when the time interval between exposure and reaction was not obvious by the clinical history, the patients were instructed to continue drug intake for two more days at home.20

The diagnosis of βL allergy was established when skin tests, specific IgE or DPT were positive. In such cases, an alternative βL was tested.

All legal guardians were fully informed about the procedures and signed an informed consent. The study was approved by the hospital ethics committee.

Statistical analysisData was summarized with mean and standard-deviation (SD) or absolute (N) and relative (%) frequencies. For analysis of the relationship of variables among patients with confirmed or excluded βL allergy the Chi-square test or Fisher exact test was used for categorical variables and when differences were significant the Bonferroni method was applied for pairwise comparisons. For continuous variables the Student t-test was used.

All statistical tests were carried out for two-tailed significance and a p<0.05 was considered significant.

SPSS software (SPSS version 24.0, SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA) was used.

ResultsTwo hundred and twenty children (53.2% females) with a mean age of 6.5 years (SD=4.2) were evaluated for suspected βL allergy and all completed the diagnostic work-up during the study period.

A further 29 children studied during this period were excluded since they did not complete the drug allergy diagnostic work-up. No analysis was performed referring to these patients’ data.

The mean time that elapsed between the reaction and the clinical assessment was 2.9 years (SD=3.3). The most frequently implicated drugs were AX/CL (47.7%) and amoxicillin (40.5%). βL were prescribed for tonsillitis in 32.7%, otitis in 22.7% and unspecified upper airways infection in 19.1%. Cutaneous manifestations were the most frequently reported presentation (96.9%) and the most common maculopapular exanthema (MPE). In 131 cases (59.5%) the reaction was non-immediate, in 10.5% immediate and in the remaining cases the time of onset was unknown. In 66 cases (30%) there was no history of previous exposure to the suspected drug, while 42 children (19%) had previous exposure with a similar reaction.

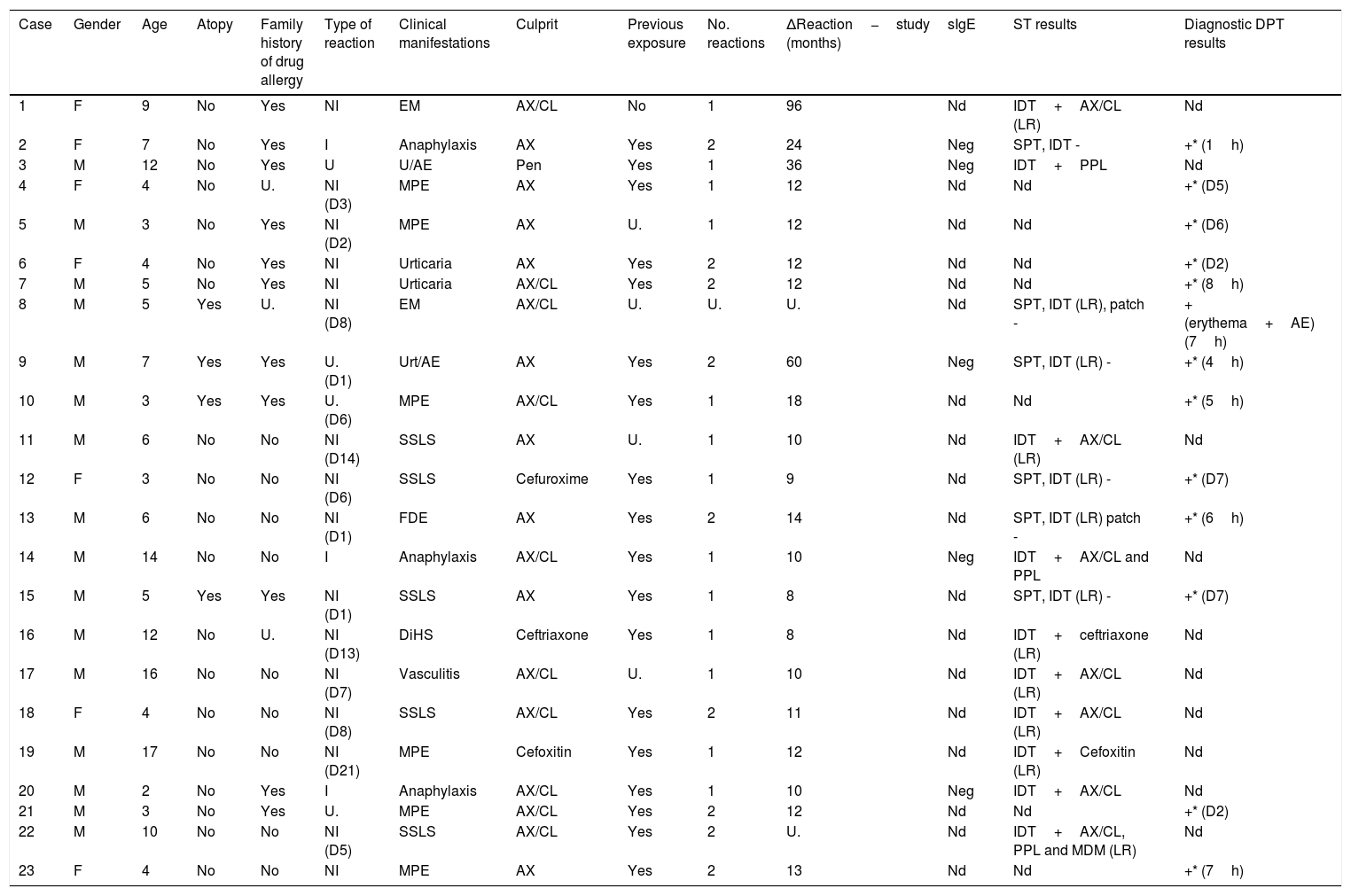

After completing the drug allergy work-up, 23 children (10.5%) were diagnosed with allergy to βL. Three of the positive cases belonged to the group that reported immediate reactions (3/23 cases, confirmation rate of 13%) and 16 to the group with non-immediate reactions (16/131, confirmation rate of 12.2%). It was possible to obtain a safe alternative βL in all of these positive cases. Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of all confirmed cases.

| Case | Gender | Age | Atopy | Family history of drug allergy | Type of reaction | Clinical manifestations | Culprit | Previous exposure | No. reactions | ΔReaction−study (months) | sIgE | ST results | Diagnostic DPT results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | F | 9 | No | Yes | NI | EM | AX/CL | No | 1 | 96 | Nd | IDT+AX/CL (LR) | Nd |

| 2 | F | 7 | No | Yes | I | Anaphylaxis | AX | Yes | 2 | 24 | Neg | SPT, IDT - | +* (1h) |

| 3 | M | 12 | No | Yes | U | U/AE | Pen | Yes | 1 | 36 | Neg | IDT+PPL | Nd |

| 4 | F | 4 | No | U. | NI (D3) | MPE | AX | Yes | 1 | 12 | Nd | Nd | +* (D5) |

| 5 | M | 3 | No | Yes | NI (D2) | MPE | AX | U. | 1 | 12 | Nd | Nd | +* (D6) |

| 6 | F | 4 | No | Yes | NI | Urticaria | AX | Yes | 2 | 12 | Nd | Nd | +* (D2) |

| 7 | M | 5 | No | Yes | NI | Urticaria | AX/CL | Yes | 2 | 12 | Nd | Nd | +* (8h) |

| 8 | M | 5 | Yes | U. | NI (D8) | EM | AX/CL | U. | U. | U. | Nd | SPT, IDT (LR), patch - | + (erythema+AE) (7h) |

| 9 | M | 7 | Yes | Yes | U. (D1) | Urt/AE | AX | Yes | 2 | 60 | Neg | SPT, IDT (LR) - | +* (4h) |

| 10 | M | 3 | Yes | Yes | U. (D6) | MPE | AX/CL | Yes | 1 | 18 | Nd | Nd | +* (5h) |

| 11 | M | 6 | No | No | NI (D14) | SSLS | AX | U. | 1 | 10 | Nd | IDT+AX/CL (LR) | Nd |

| 12 | F | 3 | No | No | NI (D6) | SSLS | Cefuroxime | Yes | 1 | 9 | Nd | SPT, IDT (LR) - | +* (D7) |

| 13 | M | 6 | No | No | NI (D1) | FDE | AX | Yes | 2 | 14 | Nd | SPT, IDT (LR) patch - | +* (6h) |

| 14 | M | 14 | No | No | I | Anaphylaxis | AX/CL | Yes | 1 | 10 | Neg | IDT+AX/CL and PPL | Nd |

| 15 | M | 5 | Yes | Yes | NI (D1) | SSLS | AX | Yes | 1 | 8 | Nd | SPT, IDT (LR) - | +* (D7) |

| 16 | M | 12 | No | U. | NI (D13) | DiHS | Ceftriaxone | Yes | 1 | 8 | Nd | IDT+ceftriaxone (LR) | Nd |

| 17 | M | 16 | No | No | NI (D7) | Vasculitis | AX/CL | U. | 1 | 10 | Nd | IDT+AX/CL (LR) | Nd |

| 18 | F | 4 | No | No | NI (D8) | SSLS | AX/CL | Yes | 2 | 11 | Nd | IDT+AX/CL (LR) | Nd |

| 19 | M | 17 | No | No | NI (D21) | MPE | Cefoxitin | Yes | 1 | 12 | Nd | IDT+Cefoxitin (LR) | Nd |

| 20 | M | 2 | No | Yes | I | Anaphylaxis | AX/CL | Yes | 1 | 10 | Neg | IDT+AX/CL | Nd |

| 21 | M | 3 | No | Yes | U. | MPE | AX/CL | Yes | 2 | 12 | Nd | Nd | +* (D2) |

| 22 | M | 10 | No | No | NI (D5) | SSLS | AX/CL | Yes | 2 | U. | Nd | IDT+AX/CL, PPL and MDM (LR) | Nd |

| 23 | F | 4 | No | No | NI | MPE | AX | Yes | 2 | 13 | Nd | Nd | +* (7h) |

Legend: U. – unknown; EM – erythema multiforme; NI – non-immediate; AX/CL – amoxicillin/clavulanic acid; IDT – intradermal test; nd – not done; ST – skin tests, Pen – penicillin; MPE – maculopapular exanthema; SSLS – serum sickness-like syndrome; Urt/AE – urticaria/angioedema; FDE – fixed drug eruption; DiHS – drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome; LR: late reading. D: day, AE: angioedema; *: reproducible reaction.

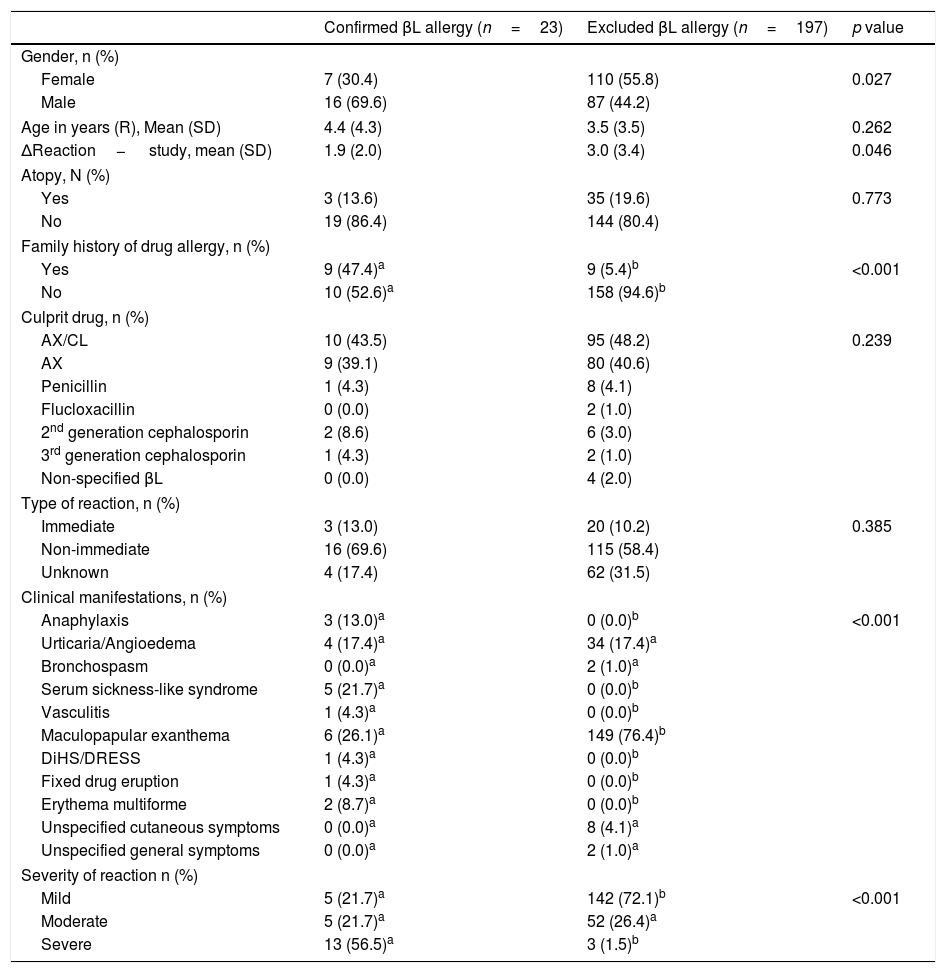

In order to investigate potential risk factors, we compared the two groups of children with confirmed and excluded βL allergy regarding demographic and clinical characteristics (Table 2). The likelihood of βL allergy was significantly higher in children with a family history of drug allergy (47.4% vs. 5.4%, p<0.001) and in those with a shorter time interval between the reaction and the evaluation (p=0.046). On the other hand, the probability of not confirming βL allergy is greater in children reporting less severe reactions (p<0.001) and MPE (p<0.001).

Demographic and clinical characteristics.

| Confirmed βL allergy (n=23) | Excluded βL allergy (n=197) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender, n (%) | |||

| Female | 7 (30.4) | 110 (55.8) | 0.027 |

| Male | 16 (69.6) | 87 (44.2) | |

| Age in years (R), Mean (SD) | 4.4 (4.3) | 3.5 (3.5) | 0.262 |

| ΔReaction− study, mean (SD) | 1.9 (2.0) | 3.0 (3.4) | 0.046 |

| Atopy, N (%) | |||

| Yes | 3 (13.6) | 35 (19.6) | 0.773 |

| No | 19 (86.4) | 144 (80.4) | |

| Family history of drug allergy, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 9 (47.4)a | 9 (5.4)b | <0.001 |

| No | 10 (52.6)a | 158 (94.6)b | |

| Culprit drug, n (%) | |||

| AX/CL | 10 (43.5) | 95 (48.2) | 0.239 |

| AX | 9 (39.1) | 80 (40.6) | |

| Penicillin | 1 (4.3) | 8 (4.1) | |

| Flucloxacillin | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.0) | |

| 2nd generation cephalosporin | 2 (8.6) | 6 (3.0) | |

| 3rd generation cephalosporin | 1 (4.3) | 2 (1.0) | |

| Non-specified βL | 0 (0.0) | 4 (2.0) | |

| Type of reaction, n (%) | |||

| Immediate | 3 (13.0) | 20 (10.2) | 0.385 |

| Non-immediate | 16 (69.6) | 115 (58.4) | |

| Unknown | 4 (17.4) | 62 (31.5) | |

| Clinical manifestations, n (%) | |||

| Anaphylaxis | 3 (13.0)a | 0 (0.0)b | <0.001 |

| Urticaria/Angioedema | 4 (17.4)a | 34 (17.4)a | |

| Bronchospasm | 0 (0.0)a | 2 (1.0)a | |

| Serum sickness-like syndrome | 5 (21.7)a | 0 (0.0)b | |

| Vasculitis | 1 (4.3)a | 0 (0.0)b | |

| Maculopapular exanthema | 6 (26.1)a | 149 (76.4)b | |

| DiHS/DRESS | 1 (4.3)a | 0 (0.0)b | |

| Fixed drug eruption | 1 (4.3)a | 0 (0.0)b | |

| Erythema multiforme | 2 (8.7)a | 0 (0.0)b | |

| Unspecified cutaneous symptoms | 0 (0.0)a | 8 (4.1)a | |

| Unspecified general symptoms | 0 (0.0)a | 2 (1.0)a | |

| Severity of reaction n (%) | |||

| Mild | 5 (21.7)a | 142 (72.1)b | <0.001 |

| Moderate | 5 (21.7)a | 52 (26.4)a | |

| Severe | 13 (56.5)a | 3 (1.5)b | |

Different letters a, b denote significant differences among columns in each demographic or clinic characteristic according to Bonferroni's multiple comparison test.

Legend: Age in years (R) – age in years at the time of the reaction; SD – standard deviation; AX/CL – amoxicillin/clavulanic acid; DiHS/DRESS drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome/drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms.

Regarding the safety of the less extensive diagnostic protocol in milder reactions, namely direct DPT with culprit drug without previous skin testing we found that it was safe since only seven (4.2%) of 167 children presented a positive DPT with a reaction similar to the index one.

DiscussionIn this study, a large group of children with a suspected history of hypersensitivity reaction to βLs was assessed. Only 10.5% were confirmed to be allergic to βLs , after diagnostic work-up, similar to other studies.1,8,10,11,20

Although MPE represent the majority of suspected reactions caused by βL in children, our study confirmed a low positivity rate (3.9%; six confirmed in 155 suspected). However, in the absence of clearly distinctive characteristics of MPE related to viral infections, an allergy diagnosis work-up is mandatory in all cases.

Recently there has been intense debate regarding the diagnostic protocols in allergy to βL in children that has attracted renewed interest on this topic. Several studies have confirmed the low diagnostic value of skin tests in this age group with mild non-immediate reactions to βLs. In this setting, their utility is being questioned, especially considering that these are painful procedures that are poorly tolerated by children and, if negative, do not preclude the need for DPT to confirm the diagnosis.4,7,8,20,21

The knowledge of risk factors for a positive diagnosis could help support the decision to perform the full or the short work-up protocol and this was the primary aim of our study.

We found a significant association between a positive diagnostic work-up and family history of drug allergy (p<0.001), shorter time interval between the suspected reaction and the study (p=0.046) and more severe reactions (p<0.001). The two last findings are consistent with another study.7 Based on our results and the current literature, it is advisable to perform a drug allergy work-up as soon as possible, avoiding the first six weeks after the reaction.

To our knowledge, this is the first study showing a positive correlation between βL allergy in children and parental/sibling history of drug allergy. A recent study showed an increased risk for positive DPT to βL in children with parental history of drug allergy, but only in non-immediate reactions.10 Family history of drug allergy was mainly but not exclusively related to βL (66.7%). The limited number of children with confirmed βL allergy did not allow a multivariate analysis and this is a limitation of this study. Also, no genetic studies were performed in our study. In immediate reactions, some polymorphisms in cytokine genes have been associated with βL allergy.22 Another genome-wide association study in Spanish and Italian populations demonstrated the link between HLA-DRA genetic variants and penicillin allergy.23

Some studies reported that immediate reactions have a high probability of being confirmed after diagnostic work-up.7,8 We did not find this correlation but the high percentage of reactions with unknown chronology (30%) in this study may have contributed to the final result.

The diagnosis of βL allergy in our study was based on positive skin tests (43.5%), namely in positive IDT (seven were positive in late reading and three in immediate reading) or positive DPT (56.5%). The majority of the reactions were induced by DPT performed at day-care hospital (53.8%), with two reactions (28.6%) occurring during hospital stay and five (71.4%) when the children returned home. Six reactions to DPT (46.2%) occurred after continuing the tested drug at home. Except for one case (previously described as erythema multiform but presenting as erythema and angioedema after DPT), the clinical manifestations induced by re-exposure during DPT were similar to the index reaction. However, in non-immediate reactions, the time of onset did not reproduce the index reaction in the majority of cases. In two cases the reactions had a similar delay of index reaction, two occurred earlier and three later. There were no precise data in the remaining five cases.

In the study of these children, a less extensive protocol was followed in all mild reactions, including immediate and non-immediate ones, as usual in our Department. However, the majority of those mild reactions were non-immediate or with unknown chronology. Only six children reported mild immediate reactions and they performed a direct DPT and none reacted. This protocol confirmed to be safe since only seven of the167 children presented a positive DPT similar to the index one. Globally DPT was positive in 6.2% of cases (13/210 children) and in 4.2% of children undergoing direct DPT without previous skin testing (7/167). The safety of this approach is in accordance with other studies concerning mild non-immediate reactions,1,4,24 but few studies support the use of this strategy for mild immediate reactions to βLs in children.10,25

A crucial issue that lacks consensus is the optimal length for DPT in the diagnosis of non-immediate reactions, with protocols ranging from one to five days.5,8,11,20,21,26 Some groups personalize the length of DPT according to the timing of the index reaction.5,7 Although shorter protocols are more convenient and have fewer side effects, some authors defend that extended protocols may increase the sensitivity of DPT and the confidence in subsequent use of the drug.4 A recent study showed that the two protocols are comparable concerning these issues.5 This question was not evaluated by our study. We performed a three-day protocol (one in the hospital and two at home) and as described above, the majority of the reactions were induced by DPT performed at day-care hospital. The time of onset of reactions after continued DPT at home did not reproduce the index reaction in most of the cases, with some reactions after DPT occurring sooner and others later.

In conclusion, only 10.5% of the assessed children in this study were confirmed as allergic to βL. The less extensive diagnostic protocol showed to be safe in milder reactions. This study highlights first degree family history of drug allergy as a risk factor for a positive diagnostic work-up. Larger studies are required, particularly genetic studies to accurately determine future risk for βL allergy in children.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.