Food allergy is a highly prevalent disorder. Anaphylaxis is the most serious consequence, and reactions often occur in schools. In the event of anaphylactic reaction prompt treatment is key and should be initiated by school personnel. The aim of this study was to assess the level of knowledge of the management of anaphylaxis, and to determine if it improves after a training session among school staff.

Materials and MethodsDescriptive study carried out by means of a pre-and post-training questionnaire completed by participants before and after a training session held at the school. Data from the same participants before and after the educational session were compared using McNemar’s test.

ResultsThree schools were enrolled (with a total of 38 children with food allergy) and 53 participants (85% teachers, 15% canteen staff) were trained. In the pre-training surveys, 83% said they had a Student’s Allergic Reaction Management Plan, 56% had met with parents, 83% recognised some symptoms of allergic reaction but only 41% recognised anaphylaxis, 16% knew when to use adrenaline, 15% knew how to use it and 19% knew how to act after administering it. In the post-training questionnaires, 100% were satisfied and believed they had improved their knowledge, 93% recognised anaphylaxis and 95% the treatment of choice.

ConclusionsPrior to the intervention their knowledge was insufficient, but it improved considerably after simple training. It also increased the confidence of the staff, which will be decisive when responding to an anaphylactic reaction. We believe that a compulsory training programme should be implemented universally in all schools.

Anaphylaxis is a severe, potentially fatal, systemic allergic reaction that occurs suddenly after contact with an allergy-causing substance.1

Food allergy is a common and increasing problem, with the main burden occurring in childhood.2 Allergic disease affects up to 25% of school-age children in Europe; and 4–7% of primary school children have food allergy.3 Food allergy can manifest with a number of symptoms, such as urticaria or swelling (facial angioedema), hoarseness or voice changes, wheezing, dyspnoea and sneezing, abdominal pain, diarrhoea, vomiting, and/or cardiovascular problems in the form of dizziness or loss of consciousness. The most common foods causing allergic reactions are cow’s milk, chicken eggs, peanuts, tree nuts, wheat, soy, fish and shellfish,4 with allergy to peanuts, tree nuts, eggs and milk the most likely to cause anaphylaxis.2 As these reactions can be life-threatening, they require the rapid administration of adrenaline. Adrenaline auto-injectors are the first-aid measure of choice for this purpose and can be administered by non-healthcare professionals.5 However, these are complex devices requiring comprehensive knowledge for appropriate use.

Although anaphylaxis is rare in school-age children, there have been reports of anaphylaxis and food allergy deaths at school.6 Anaphylaxis is estimated to occur at a rate of one episode per 10 000 children per year, and 82% of these episodes occur in school-age children.7 A survey conducted in the United Kingdom found that 61% of schools had at least one child at risk of anaphylaxis (i.e. carried injectable adrenaline or had a history of anaphylaxis).7 Food allergy or anaphylactic reactions occur at school in 10 %–18 % of cases.8 Due to the ubiquitous nature of food allergens in schools (such as lunch and break times, lessons, science projects, etc), and considering that approximately 25% of anaphylaxis cases occur in children with previously undiagnosed allergy,9,10 it is essential that all schools are properly prepared and trained, even if they do not have students with a history of anaphylaxis enrolled at that time.4,10 Fatalities due to anaphylaxis were noted to be overrepresented among teenagers, especially those with underlying asthma, and among children with peanut, tree nut, or milk allergy. Although the frequency of food-induced anaphylaxis may be higher in preschool-age children compared to older ones, most food-allergic reactions in preschool- and school-age children are not anaphylaxis and deaths are rare.9

Sicherer and Mahr reported that nine of 32 fatalities from food allergy among preschool- and school-age children in the United States occurred in school and were mainly associated with significant delays in the administration of adrenaline.9

Unfortunately, schools are frequently unprepared. According to the EAACI/GA2LEN Task Force on the allergic child at school position paper,4 “information about allergies is often not communicated to the school, leaving the child exposed to avoidable risk. Where management plans are provided by allergists, they are often not implemented by the school especially during extraordinary activities such as school holidays/field trips”. Moreover, they report that emergency medication is often not readily available (only in 12% of schools in a UK survey) and teachers are poorly trained (only 48% of schools had a trained teacher).4 Several studies report that this lack of knowledge among teachers can be improved by training and educational sessions.5,13–15

The Task Force4 also identified an absence of European legislation specific to allergic children at school. Teachers’ lack of medical training means that “under current legislations, teachers have no specific duties in terms of child health protection as this responsibility lies entirely with the school/health care system”. Thus, in view of the increasingly high prevalence of allergy in school-age children and the need for prompt treatment of potentially fatal (albeit rare) anaphylactic reactions at school, this Task Force has developed some recommendations that describe an ideal model of care centred on the allergic child at school.4 Schools should arrange regular allergy training for staff facilitated by liaison with relevant health care providers.

The purpose of this study was to explore the current understanding of anaphylaxis and its management among school staff, and to evaluate how a short theoretical and practical intervention programme might influence this knowledge. Secondly, we evaluated whether this programme improved staff self-confidence and self-reliance to deal with anaphylaxis at school.

Materials and methodsOur study was performed between December 2015 and January 2018. We carried out our educational programme in three schools at the request of our patient’s relatives. The only inclusion criteria were the request of the parents and acceptance by the school management.

An educational session was developed, consisting of two parts: a theoretical part and a practical part. The theoretical part took 40–50min and was always presented in the same standardised way using digital slides. It was delivered by a paediatric allergist and included several aspects: definition of allergy, pathophysiology of allergic reactions, prevention of food allergic reactions (including communication with family and development of a Student’s Allergic Reaction Management Plan), recognition of allergic reaction (including anaphylaxis), management and medication needed for allergic reaction (anaphylaxis included), use of the adrenaline auto-injector, correct performance after injecting adrenaline, and some legal aspects and official recommendations. A document with all this information was also provided to the participants. The practical part took 10−20min, was performed by a paediatric nurse and covered the use of auto-injectors with an auto-injector simulator.

A questionnaire was completed by the school staff before and after the educational session (Appendix 1 and Appendix 2). In the pre-training questionnaire, we evaluated the following items: school, position (teacher/school canteen staff), age of students in their charge, number of students in their charge with food allergy and/or history of anaphylaxis, availability of a Student’s Allergic Reaction Management Plan, knowledge of the location of the adrenaline auto-injector, previous meeting with parents/guardians of food-allergic children, ability to recognise an allergic reaction and anaphylaxis, knowledge about the medication to administer during anaphylaxis, and knowledge of when and how to use the adrenaline auto-injector and what to do after administering adrenaline. In the subsequent questionnaire we evaluated: perception of improvement of knowledge of food allergy, anaphylaxis, and about when and how to administer adrenaline, degree of satisfaction after the educational session, fulfilment of expectations, and knowledge of the definition and management of anaphylaxis; we also asked participants to identify previous errors such as lack of availability of a Student’s Allergic Reaction Management Plan, insufficient communication with parents/guardians, not having located the adrenaline auto-injector, not checking the expiry date periodically, not knowing exactly when and how to use the auto-injector, and not knowing what to do after the administration of adrenaline. Having taken into account that some the questions we proposed may not be easy to answer, even for healthcare staff, we adapted our list of acceptable responses accordingly. Thus, we considered the answer to be correct when the following criteria were met: the respondent recognised some symptoms of allergic reactions correctly if they described at least two of the main symptoms (skin, respiratory, cardiocirculatory, digestive involvement); they recognised anaphylaxis correctly if they described respiratory or cardiocirculatory involvement, in addition to skin involvement; they had a correct knowledge about when to use the adrenaline auto-injector if they referred to respiratory or cardiocirculatory involvement; they had correct knowledge about how to use the adrenaline auto-injector if they mentioned the correct route (intramuscular) and site of administration (leg); and they had correct knowledge about how to act after use of the adrenaline auto-injector if they placed a call to emergency services.

Statistical analysisStatistical analysis was performed with IBM SPSS Statistics© 25.0. Frequencies are reported as percentages. Continuous data are presented as median with interquartile range, as appropriate with range (minimum/maximum). Pre- and post-training data from the same participants were compared using McNemar’s test. A p value ≤ 0.05 was considered significant.

ResultsIn total, 53 people participated in the educational programme: 80% were teachers and 20% school canteen staff. Their mean age was 43 (25–64) years. There were no statistically significant differences in age between the teachers and the staff in charge of the dining room. The age of the students was between three and 12 years old with a total of 38 students with food allergy. Since food allergy is a common problem, we found that 70% of the respondents claimed to have at least one student in their charge with a food allergy, with a mean of three students. Nine percent of the participants had at least one student with a history of anaphylaxis under their supervision.

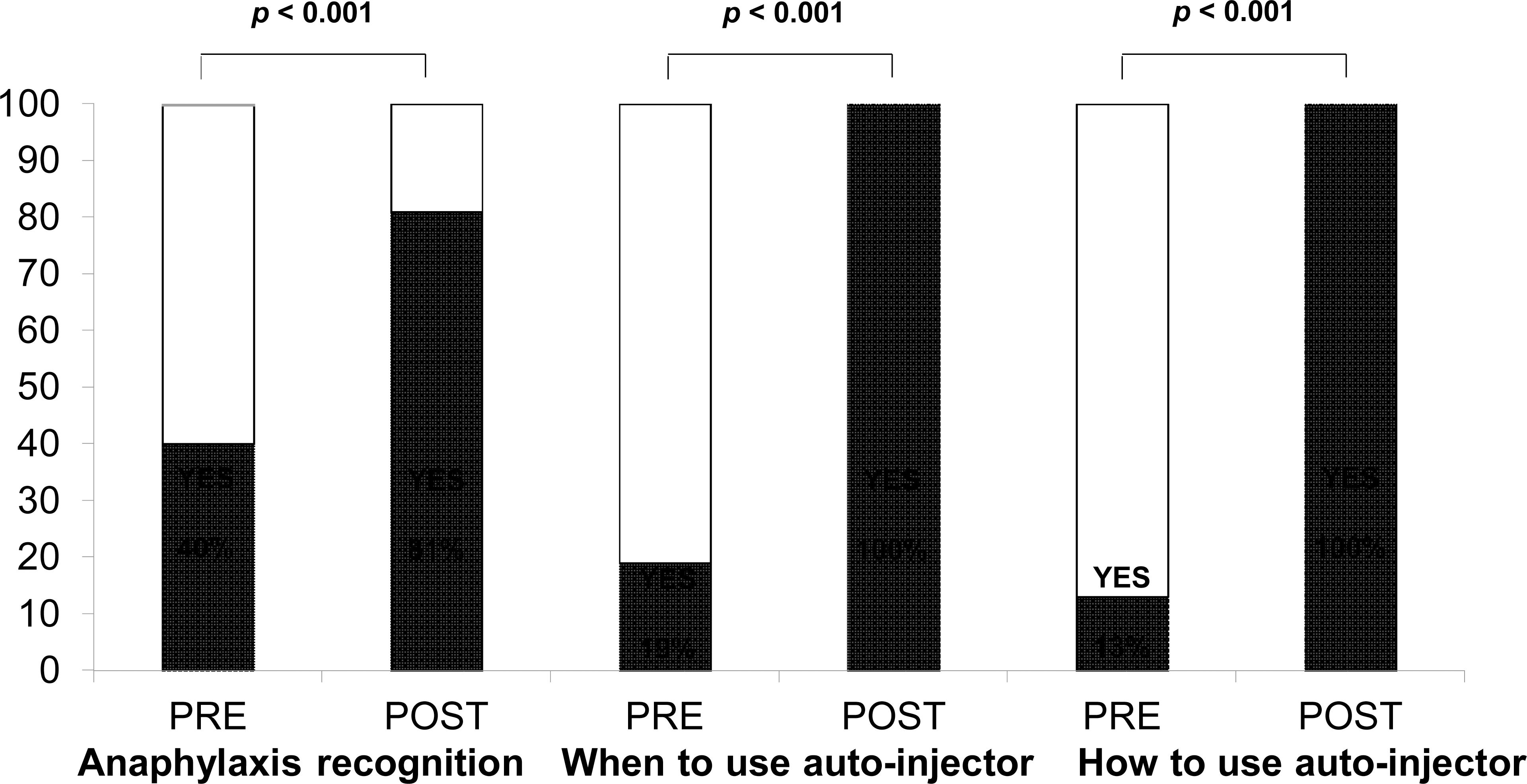

We found that there was a school protocol and it was acceptably applied: 83% of participants claimed to have a Student’s Allergic Reaction Management Plan available; 56% had had a meeting with parents/guardians of the allergic child/children in their charge; and 66% claimed to know where to find the auto-injector. Nevertheless, knowledge among participants regarding the management of anaphylaxis was poor, as shown in Table 1.

Frequency of correct answers referring to knowledge of food allergy and anaphylaxis in the pre-training questionnaire.

| Number (%) | |

|---|---|

| Correct recognition of some symptoms of allergic reaction | 42 (79.2%) |

| Correct recognition of anaphylaxis | 21 (39.6%) |

| Including adrenaline as the main medication in anaphylaxis | 24 (45.3%) |

| Correct knowledge about when to use adrenaline auto-injector | 10 (18.9%) |

| Correct knowledge about how to use adrenaline auto-injector | 7 (13.2%) |

| Correct knowledge about how to act after use of the adrenaline auto-injector | 12 (22.6%) |

There was no relationship between the fact of having a child in their charge with a history of anaphylaxis and knowledge of the concept of anaphylaxis prior to the training session (p=0.643).

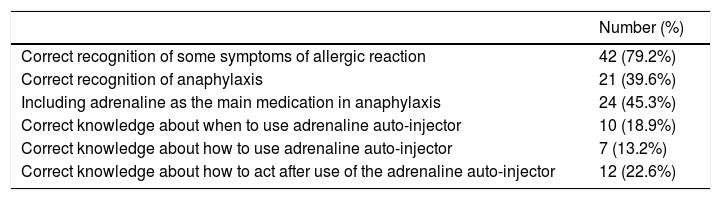

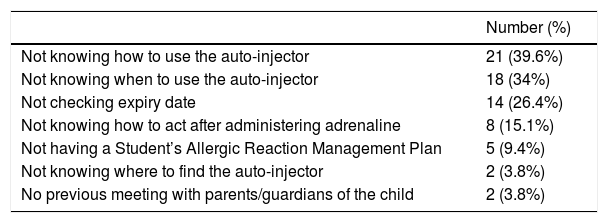

After the educational session, all participants were satisfied and believed they had improved their knowledge. The assessment of staff knowledge before and after the training session is shown in Fig. 1. Thus, after the session, 81% recognised anaphylaxis and 79% the treatment of choice. This percentage was significantly higher than that reported before the educational intervention (p<0.001). Likewise, the proportion of school staff who believed they knew when to use the auto-injector increased from 19% to 100%, with statistical significance (p<0.001), and the proportion of school personnel who believed they knew how to use it increased from 13% to 100% (p<0.001). Previously identified failures are shown in Table 2.

Frequency of previous failures detected in the post-training questionnaire.

| Number (%) | |

|---|---|

| Not knowing how to use the auto-injector | 21 (39.6%) |

| Not knowing when to use the auto-injector | 18 (34%) |

| Not checking expiry date | 14 (26.4%) |

| Not knowing how to act after administering adrenaline | 8 (15.1%) |

| Not having a Student’s Allergic Reaction Management Plan | 5 (9.4%) |

| Not knowing where to find the auto-injector | 2 (3.8%) |

| No previous meeting with parents/guardians of the child | 2 (3.8%) |

Food allergy is a problem with a high and increasing prevalence, with anaphylaxis being the most serious and potentially fatal consequence. Moreover, anaphylaxis can occur in children not previously diagnosed with food allergy. Schools are not sufficiently prepared and, in those studies that analyse the effect of an educational programme among school personnel, good results have been reported in the short- and mid-term. Nevertheless, these educational sessions should be given periodically to ensure good results in the long term. There is a lack of legislation regarding the responsibility of teachers, but there are some recommendations in this area, which include the existence of educational programmes on the management of food allergy and anaphylaxis at school. This study has two main findings: our schools are not sufficiently prepared to manage an anaphylactic reaction, and this preparation can be improved with a short educational programme. This data is consistent with the literature.

In the United States, Shah et al. found that, compared with a group of controls, teacher training improved knowledge of food allergy as assessed by means of pre-and post-training questionnaires. The number of positive responses increased significantly in the group that received training.13,14 A study conducted in Germany among preschool teachers obtained very good results.5 This was previously shown by Foster et al. in a study that addressed short-term improvement of preschool teachers’ knowledge of and attitudes towards children with allergies after a single education session.15 In our study, 70% of the school staff claimed to have at least one student with food allergy in their charge; a study carried out by Dumeier et al. in Germany among 75 preschool teachers5 found a similar percentage (81%). In the German study, an education session addressing allergies, anaphylactic emergencies, and administering auto-injectors was conducted. Attitudes and knowledge in allergies and anaphylactic emergencies were evaluated by a questionnaire and practical performance in administering auto-injectors was assessed before the education session, directly after, and 4–12 weeks after the session. In our study, staff had an average of three students in their charge with food allergy, the same as in the study by Dumeier et al.5 In our study, 9% of the participants had at least one student with a history of anaphylaxis under their supervision. In a Spanish survey 13 performed among nursery, primary, secondary and high school teachers, 3.5% had a student with history of anaphylaxis.

Knowledge prior to the session was considered insufficient, and these results are consistent with published data. In a Spanish study by Juliá-Benito et al.,13 the vast majority (82.8%) of teachers would not know what to do in the event of an anaphylactic reaction in school, similar to the percentage found in our study. As a positive outcome, we noted that most of the respondents claimed to have a Student’s Allergic Reaction Management Plan, but only half of them had met with the parents/guardian of the allergic child/children in their charge. This low percentage is probably due to the fact that some of the participants are not required to do so (specialised teachers, school canteen staff). Sixty-six percent of participants had an available rescue kit at school, lower than in the German study5 (71%), but much higher than in the study published by Rankin et al.12 (12%).

The proportion of school staff capable of recognising anaphylaxis increased significantly after the educational intervention: from 40% to 81% (p<0.001). There was also an increment in the proportion of staff who claimed to know when to use the auto-injector (from 19% to 100%) and how (from 13% to 100%), with p<0.001. Similarly, in the study by Dumeier et al.,5 the proportion of teachers who felt well-prepared for an anaphylactic emergency rose from 11% to 88% (decreasing to 79% 4–12 weeks thereafter). In fact, they found that the positive results decreased after 4–12 weeks for all items evaluated. This should encourage the development of regular educational programmes in schools. In our study, we asked for previous failures identified with the abovementioned results. We think that this is an interesting question to pose to school staff in order to improve protocols.

Finally, it is important to highlight that 100% of participants were satisfied and believed they had improved knowledge. This is a very important result, because self-confidence and self-reliance will probably help when facing a real situation.

In spite of the lack of legislation dealing specifically with the allergic child at school, there are official recommendations that include the presence in schools of people trained in recognising alarm symptoms and in providing emergency treatment with adrenaline. In this respect, schools should arrange regular allergy training for staff, facilitated by liaison with relevant health care providers. Our impression was that school staff were motivated and receptive to acquiring knowledge and training in this field, and that they felt more prepared and self-confident after this educational programme.

However, this study has several limitations. The schools were chosen at the request of the parents, not randomly. Moreover, in the analysed data, there is a mix of teachers and school canteen staff, although we do not consider this important because their knowledge should be similar. In the assessment of the meeting with parents/guardians of the child, the percentage is probably low because specialised teachers and school canteen staff do not usually meet with parents. In the post-training surveys, participants were asked if they thought they knew when and how to use the auto-injector (with an affirmative answer in 100%) but without verifying this knowledge. On the other hand, when asking in post-training surveys if they knew how to recognise anaphylaxis, they were asked to describe it, with 81% correct answers. Finally, the practice with the auto-injector before and after the practical training session was not evaluated individually, due to lack of time and personnel.

Despite these limitations, our data are robust and demonstrate two main and important findings: our schools are not sufficiently prepared to manage an anaphylactic reaction, and this preparation can be improved with a short educational programme. These data are consistent with the literature.

ConclusionsEven if recommendations for food allergy at school exist, schools do not seem to be sufficiently prepared. On a positive note, the results in terms of the knowledge and ability to manage anaphylaxis improved considerably after the educational programme. Consequently, we think that sustained training efforts are required, and school staff should receive periodic training sessions.

FundingThis study received no funding.

Conflict of interestsThe authors declare that they have no financial or non-financial competing interests.

We thank the participants for making this study possible.

We also thank SEICAP (Sociedad Española de Inmunología Clínica y Alergia Pediátrica) and Allergy Therapeutics Iberica for the Publibeca obtained to publish this article.