Aspirin-exacerbated respiratory disease (AERD), also known as aspirin-sensitive asthma, is a clinical entity known as the combination of nasal polyps, asthma, sensitivity to any medications that inhibits cyclooygenase-1 (COX-1) enzymes, namely aspirin and other non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and chronic hypertrophic eosinophilic sinusitis, as the fourth component recently added. Ingestion of aspirin/NSAIDs results in a spectrum of upper and/or lower respiratory reactions including rhinitis, conjunctivitis and bronchospasm.1 Anti-IgE mAb omalizumab therapy which is assigned to moderate to severe allergic asthma has recently evolved to be considered in patients with AERD.2

We report a 61-year-old woman admitted to the allergy department for uncontrolled severe asthma. She had initially been diagnosed with asthma 35 years ago. She had rhinitis since age 10 and had been operated for nasal polyp at age 20. She was on high-dose inhaled corticosteroid and long acting beta2 agonist combination, montelukast, nebulised salbutamol+ipratropium and fluticasone propionate as needed when she was admitted to our clinic. Although she adhered to the medication regimen she frequently needed parenteral corticosteroids because of poor control of her symptoms. She was admitted to emergency department twice or more times every month due to asthma attacks. On her physical examination bilateral biphasic rhonchi were detected. Pulmonary function test revealed obstructive pattern with fev1: 860mL (50% predicted). Skin tests with aeroallergens were positive for Dermatophagoides mix and feather mix. Level of total IgE level was 48IU/mL. She had adverse reaction with the use of aspirin prescribed for cerebrovascular disease two years ago. She had severe dyspnoea 1h after the first dose of aspirin and she needed treatment in the emergency department. Aspirin therapy was halted thereafter and she was put on clopidogrel therapy instead. A diagnosis of AERD was made based on clinical history. Oral challenge tests with aspirin were planned for definitive diagnosis but was not performed due to the unstable asthma (despite continuous treatment with double doses of formoterol fumarate/budesonide 9/320μg twice a day, montelukast 10mg/day and various cycles of systemic corticosteroids) and a FEV1 of 50% of predicted.

In July 2010, she was prescribed omalizumab 150mg every four weeks (total serum IgE 48IU/mL, body weight 75kg) to treat severe asthma symptoms. With the start of omalizumab treatment her symptoms improved significantly, FEV1 raised up to 80% of predicted and emergency visits and hospitalisations with asthma attacks never recurred. In November 2011, an oral challenge with aspirin with a cumulative dose of 775mg was performed and found negative. Accordingly for the cerebrovascular disease she started daily 300mg aspirin treatment instead of clopidogrel.

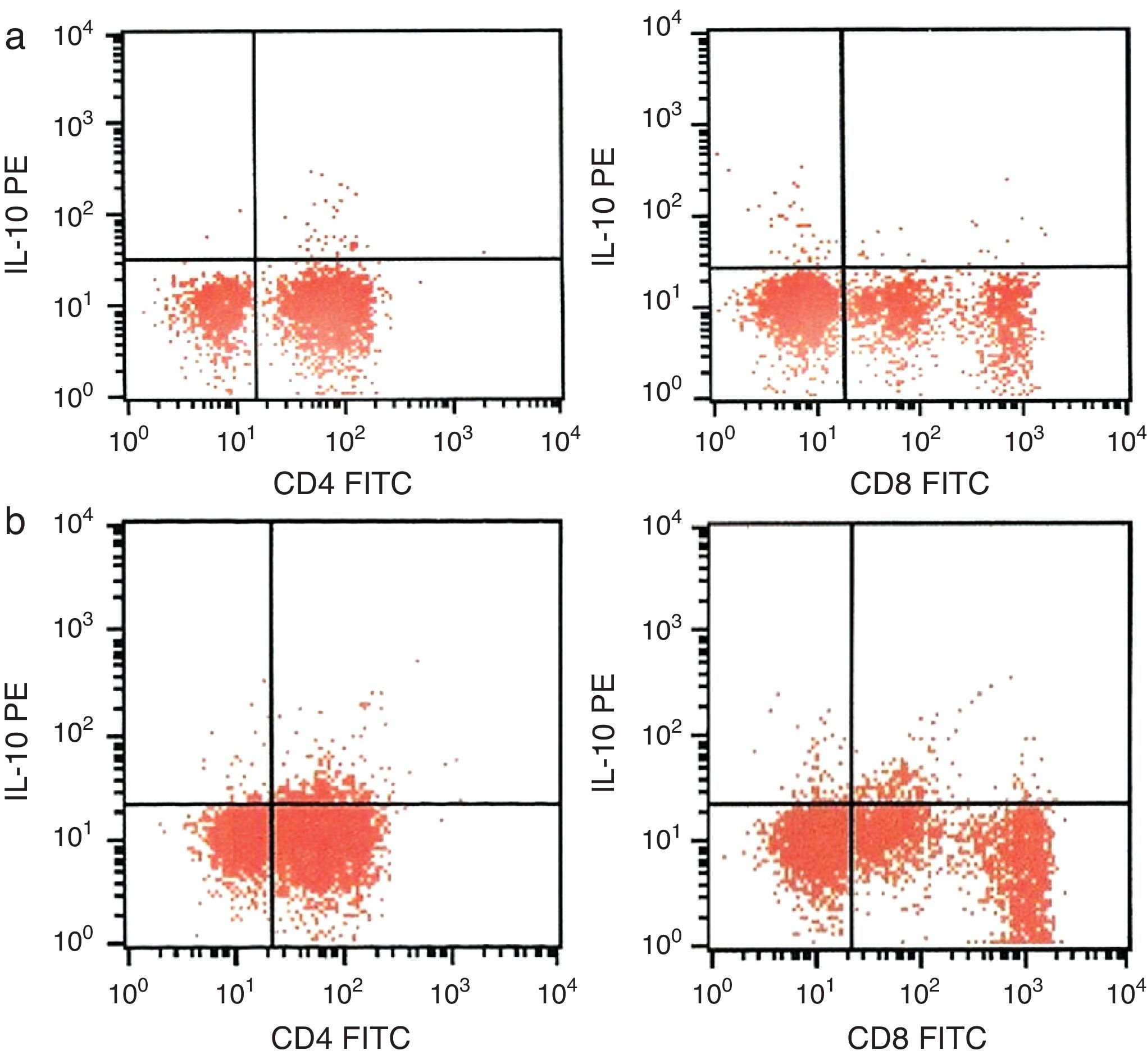

CD4+ and CD8+ T cells expressing IL-10 were assessed by flow-cytometry in whole blood obtained from the patient prior to and 15 months after the start of omalizumab therapy. Percentage of CD4+ T cells producing IL-10 was increased to 3.50% from 1.02%. Percentage of CD8+ T cells producing IL-10 was increased to 3.01% from 0.57% (Fig. 1).

Management of AERD is distinctive and must consist of prohibition of use of aspirin/NSAIDs and aspirin desensitisation performed by specialists, if possible, as well as appropriate medical treatment for asthma control.1 Omalizumab, a humanised monoclonal antibody that binds to the Fc portion of the IgE molecule, is approved for treatment of moderate to severe asthma. Seasonal and perennial allergic rhinitis, atopic dermatitis, food allergies, chronic urticaria and adjuvant use to allergen immunotherapy are clinical conditions for potential but unapproved use of omalizumab.3 Omalizumab treatment is also promising in AERD patients. Bobolea et al. have recently published the case of an 18-year-old woman with AERD presented with severe asthma symptoms successfully treated with omalizumab and improved tolerance of aspirin and other COX-1 inhibitors.2

Similarly, we present a case with AERD with severe allergic asthma treated with omalizumab for improvement in asthma symptoms who was also detected to be aspirin-tolerant at the fifteenth month of treatment. Additionally, we report IL10-producing CD4+ and CD8+ lymphocyte ratios were increased after omalizumab therapy. Studies showing beneficial effects of omalizumab in IgE mediated and non-IgE mediated conditions other than asthma or rhinitis have revealed encouraging outcomes in off-label uses of omalizumab.3 AERD may be one of the conditions to be treated with omalizumab in following years.

A promoter polymorphism in IL-10 (−1082A/G) has been reported as a risk factor significantly associated with and may contribute to the development of AERD.4 IL-10 is also known as human cytokine synthesis inhibitory factor and has pleiotropic effects in immunoregulation and inflammation. It down-regulates the expression of Th1 cytokines, MHC class II antigens, and costimulatory molecules on macrophages. IL-10 inhibits production of IFN-γ and IL-2 by Th1 lymphocytes; IL-4 and IL-5 by Th2 lymphocytes. Therefore, IL-10 is expected to have strong anti-inflammatory properties.5 IL-10 levels in severe atopic asthmatics were studied by Matsumoto et al.6 In this study the frequency of IL-10-producing CD4+CD45RO+ cells was significantly decreased in the peripheral blood of severe unstable asthmatics compared to mild and severe stable asthmatics. Moreover, with this study the possible causal relationship between high dose steroid use in severe asthmatics and low IL-10 levels was discarded.

Although no significant change in circulating IL-10 levels by ELISA was detected in moderate to severe allergic asthmatics after use of omalizumab has been reported previously7 in the present case we flow-cytometrically investigated the ratio of T lymphocyte producing IL-10 and found that the ratios are increased after omalizumab therapy.

The present case suggests that anti-IgE therapy may have a therapeutic role in patients with AERD, and that further studies – ideally randomised, double-blind, placebo controlled – are required to investigate this further. This effect of omalizumab may be related to alteration of intracellular cytokine synthesis, namely IL-10.

Ethical disclosureConfidentiality of data: The authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work centre on the publication of patient data and that all the patients included in the study have received sufficient information and have given their informed consent in writing to participate in that study.

Protection of human and animal subjects: The authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this investigation.

Right to privacy and informed consent: The authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.