Common variable immunodeficiency (CVID) is one of the most prevalent symptomatic primary immunodeficiencies (PIDs), which manifests a wide clinical variability such as autoimmunity, as well as T cell and B cell abnormalities.

MethodsA total of 72 patients with CVID were enrolled in this study. Patients were evaluated for clinical manifestations and classified according to the presence or absence of autoimmune disease. We measured regulatory T cells (Tregs) and B-cell subsets using flow cytometry, as well as specific antibody response (SAR) to pneumococcal vaccine, autoantibodies and anti-IgA in patients.

ResultsTwenty-nine patients (40.3%) have shown at least one autoimmune manifestation. Autoimmune cytopenias and autoimmune gastrointestinal diseases were the most common. A significant association was detected between autoimmunity and presence of hepatomegaly and splenomegaly. Among CVID patients, 38.5% and 79.3% presented a defect in Tregs and switched memory B-cells, respectively, whereas 69.0% presented CD21low B cell expansion. Among patients with a defect in Treg, switched memory and CD21low B cell, the frequency of autoimmunity was 80.0%, 52.2% and 55.0%, respectively. A negative correlation was observed between the frequency of Tregs and CD21low B cell population. 82.2% of patients had a defective SAR which was associated with the lack of autoantibodies.

ConclusionsAutoimmunity may be the first clinical manifestation of CVID, thus routine screening of immunoglobulins is suggested for patients with autoimmunity. Lack of SAR in CVID is associated with the lack of specific autoantibodies in patients with autoimmunity. It is suggested that physicians use alternative diagnostic procedures.

Common variable immunodeficiency (CVID) is the most frequently encountered symptomatic primary immunodeficiency (PID), known by highly heterogeneous clinical presentations and immunological features.1 The affected patients are characterised by increased susceptibility to recurrent infections, along with low levels of serum immunoglobulin (Ig), as well as reduced specific antibody response to protein and polysaccharide antigens.2 Patients may also have a wide variety of non-infectious complications, including enteropathy, lymphoproliferative disorders, malignancy, and autoimmune diseases.3

The association of CVID and autoimmunity is well recognised in several studies.4,5 It is proposed that 20–40% of CVID patients have autoimmune complications6,7 which are poorly understood and in some cases are difficult to manage.1,8 The most common autoimmune disorder observed in CVID is autoimmune cytopenia including idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP) and autoimmune haemolytic anaemia (AIHA), but autoimmune enteropathies and autoimmune rheumatological and dermatological disorders have also been reported.4,6,7,9,10 Defects in the frequency and function of B- and T-cell subsets, especially regulatory T cells (Tregs), have been described in CVID patients with autoimmunity.11,12

The aim of this study was to assess the prevalence of autoimmune manifestations in patients with CVID and to evaluate the probable associations between autoimmunity and other clinical and immunological features in these patients.

Patients and methodsStudy design and patientsAmong all registered patients in the national registry of PID patients,13,14 a total of 72 patients with CVID who were diagnosed and treated at the Children's Medical Center affiliated to Tehran University of Medical Sciences agreed to participate in this study. The diagnosis was made according to standard criteria,15,16 which included a reduction of at least two serum immunoglobulin (Ig) isotypes (IgG, IgA, and IgM) by two SDs from normal mean values for age where no other cause can be identified for the immune defect. We excluded patients under four years of age to rule out a probable diagnosis of transient hypogammaglobulinaemia of infancy. The study was performed in 2015–2016 and approved by the ethics committee of Tehran University of Medical Sciences (ref: 94-01-159-28966 and 94-02-154-29492). Informed consent was obtained from patients or their parents.

MethodsA detailed questionnaire was completed by interview for all patients to record demographic data, clinical and laboratory data, past medical history of documented autoimmunity, recurrent and chronic infections, and other complications. At diagnosis, serum levels of IgG, IgA, IgM, IgE and specific antibody responses against diphtheria and tetanus toxoids and pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine as well as lymphocyte subsets were measured using standard immunological methods.

We also evaluated a number of parameters and cell types which were involved in the pathogenesis or diagnosis of autoimmunity in our study. The absolute count and percentage of Tregs and B cell subsets (including naive, marginal zone-like, switched memory, transitional and CD21low B cells) were assessed using flow cytometry analysis as previously described by Arandi et al.17,18 and Yazdani et al.19 IgG anti-IgA antibody levels were measured by the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay method as previously described.20 The diagnosis of autoimmunity was based on clinical and complementary paraclinical findings such as endoscopy, colonoscopy and biopsy results, laboratory tests [complete blood count (CBC), direct coombs test, antinuclear antibody profile (ANA profile), fluorescent antinuclear antibody test (FANA), anti-double-stranded DNA (anti-dsDNA) and other auto-antibodies] and radiological studies as previously described.21 The criteria for inclusion in the autoimmunity group were the presentation of an autoimmune disorder at the time of study or a history of autoimmunity before or after the diagnosis of CVID. This diagnosis was confirmed either by an immunologist involved directly in the patient's clinical care or by a related subspecialist at a referral hospital.

Statistical analysisValues were expressed as frequency (number and percentage), mean±standard deviation and median (interquartile range, IQR), as appropriate. Fisher's exact test and chi-square tests were used for 2×2 comparison of categorical variables, whereas t-tests, one-way ANOVA and the non-parametric equivalent of them were used to compare numerical variables. Pearson's and Spearman correlation coefficients were calculated for assessment of the correlation between parametric and non-parametric variables, respectively. Shapiro–Wilks tests were used to check the normality assumption for a variable; so according to this assumption a parametric or non-parametric test was done. Statistical analyses were performed using the STATA software, version 12 and SPSS software package, version 22 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

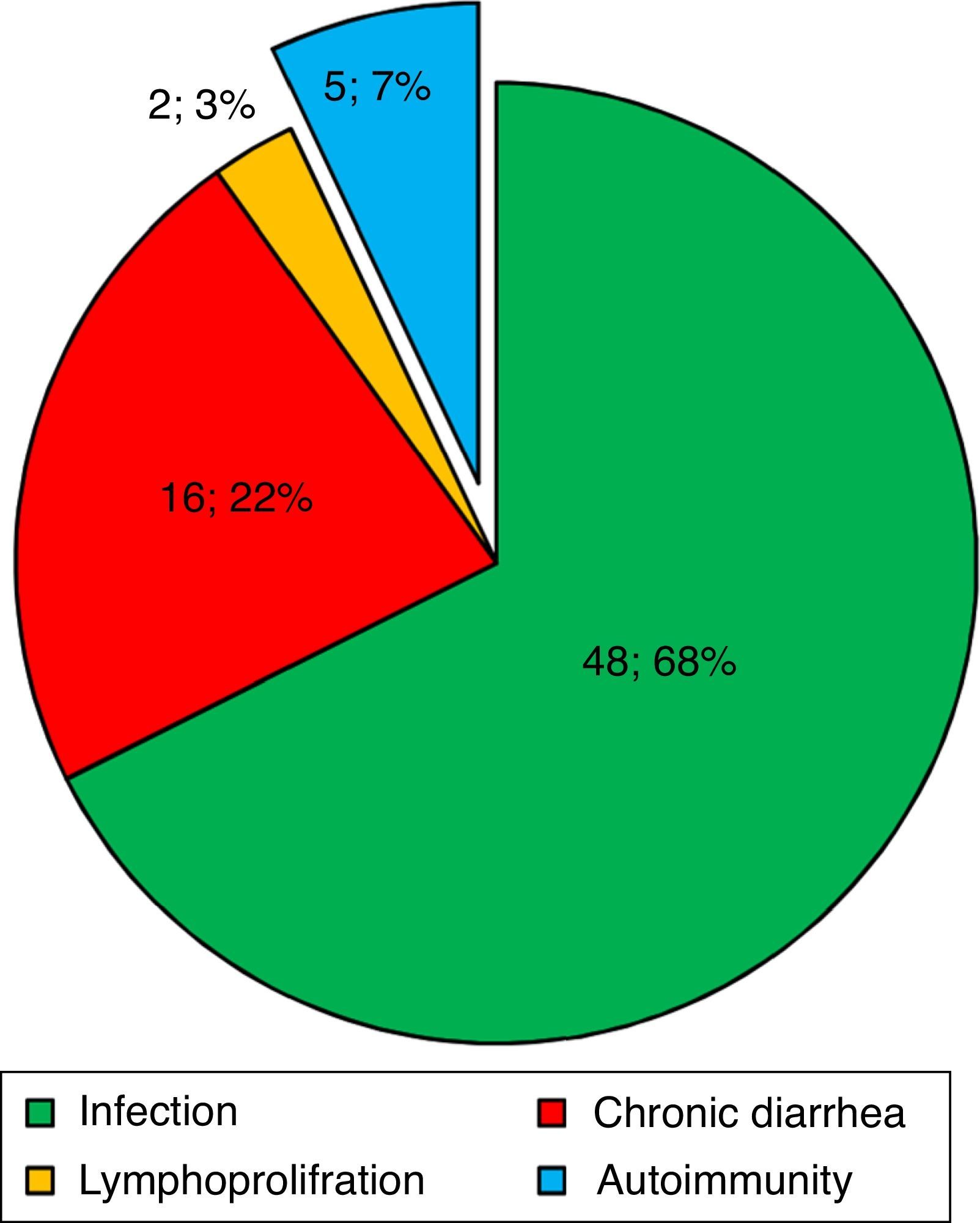

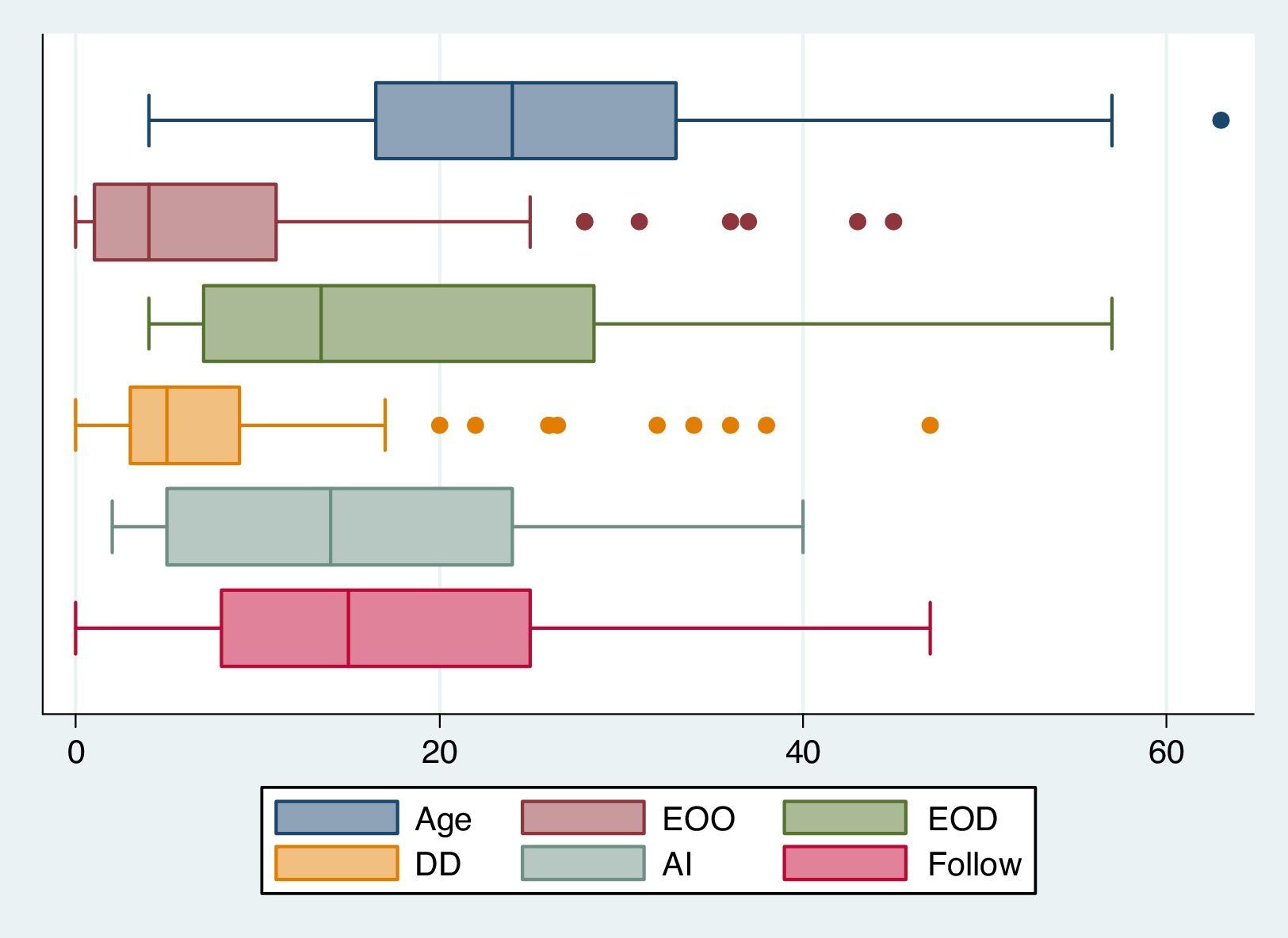

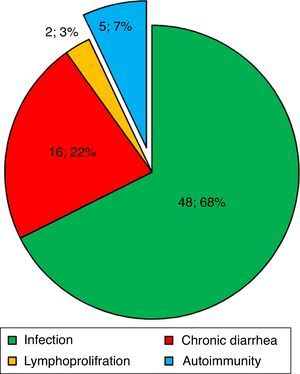

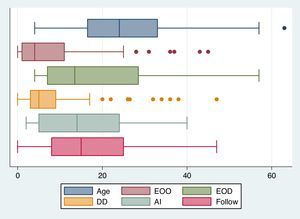

ResultsBaseline demographic dataA total of 72 CVID patients (41 male [56.9%] and 31 female [43.1%]) with a median (IQR) age at diagnosis of 13.50 (28.75–7.0) years were enrolled in this study. The patients’ characteristics are summarised in Table 1. Patients were followed for 1190.7 patient-years with a mean follow-up period of 16.77 years per patient. The most prevalent first presentation in these patients had been an infection (Fig. 1) and most patients had experienced pneumonia (22, 30.6%). Five patients (7.0%) had shown an autoimmune complication (ITP, insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus [IDDM], Vitiligo, AIHA and inflammatory bowel disease [IBD]) as the first presentation of the disease. History of autoimmunity was recorded in 29 patients (40.3%), eight of whom had had more than one autoimmune disorder during the course of the disease. Among the CVID patients with autoimmune complications, 44.0% had had the first episode of autoimmunity prior to the diagnosis of CVID and 20.0% had developed autoimmune symptoms concurrently at the time of the diagnosis of CVID. The rate of autoimmunity before diagnosis and immunoglobulin replacement therapy was 49.5 patient-years, whereas this amount was 43 patient-years after diagnosis and starting therapy (Fig. 2).

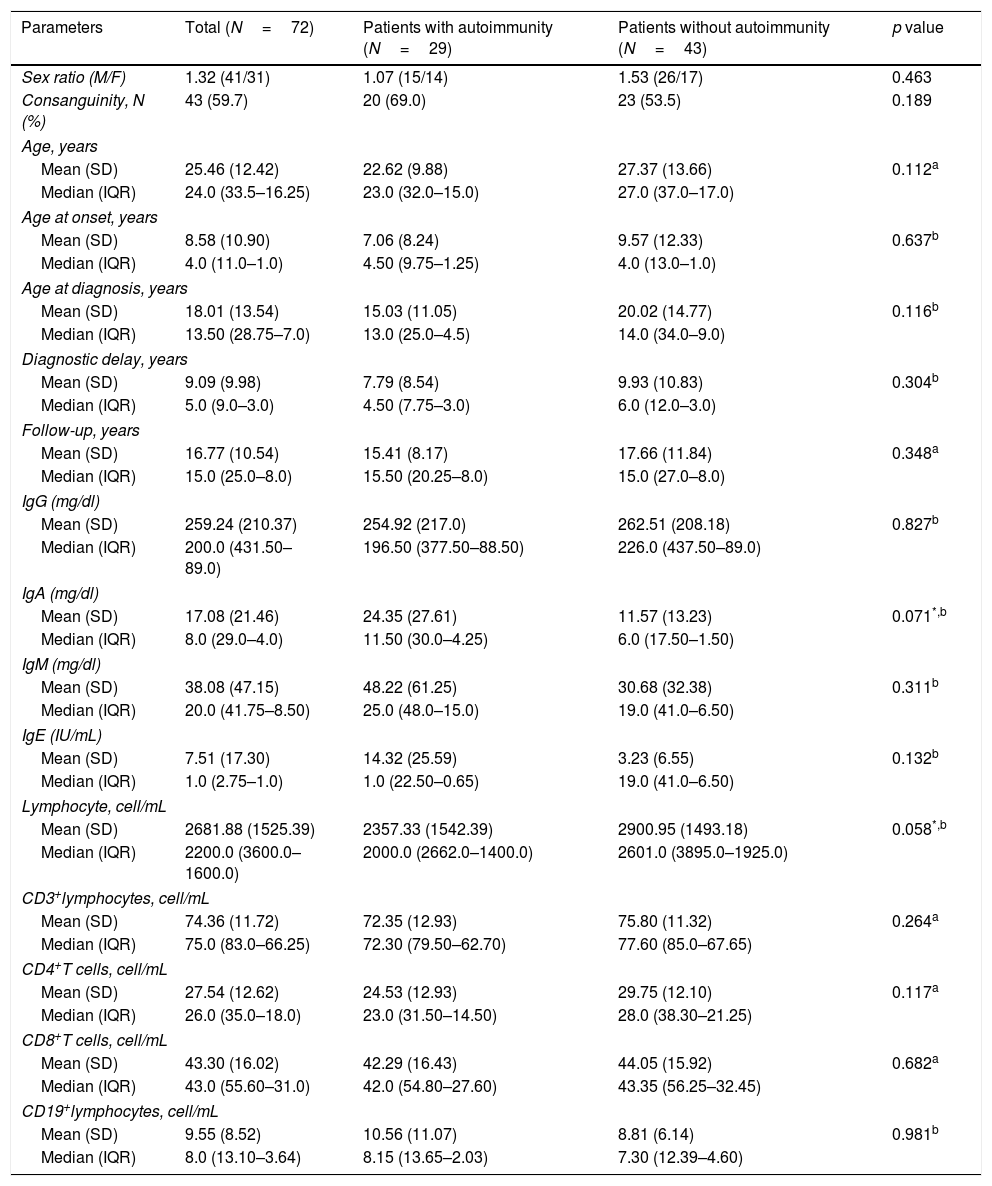

Demographic and corresponding immunological data for CVID patients at the time of diagnosis.

| Parameters | Total (N=72) | Patients with autoimmunity (N=29) | Patients without autoimmunity (N=43) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex ratio (M/F) | 1.32 (41/31) | 1.07 (15/14) | 1.53 (26/17) | 0.463 |

| Consanguinity, N (%) | 43 (59.7) | 20 (69.0) | 23 (53.5) | 0.189 |

| Age, years | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 25.46 (12.42) | 22.62 (9.88) | 27.37 (13.66) | 0.112a |

| Median (IQR) | 24.0 (33.5–16.25) | 23.0 (32.0–15.0) | 27.0 (37.0–17.0) | |

| Age at onset, years | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 8.58 (10.90) | 7.06 (8.24) | 9.57 (12.33) | 0.637b |

| Median (IQR) | 4.0 (11.0–1.0) | 4.50 (9.75–1.25) | 4.0 (13.0–1.0) | |

| Age at diagnosis, years | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 18.01 (13.54) | 15.03 (11.05) | 20.02 (14.77) | 0.116b |

| Median (IQR) | 13.50 (28.75–7.0) | 13.0 (25.0–4.5) | 14.0 (34.0–9.0) | |

| Diagnostic delay, years | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 9.09 (9.98) | 7.79 (8.54) | 9.93 (10.83) | 0.304b |

| Median (IQR) | 5.0 (9.0–3.0) | 4.50 (7.75–3.0) | 6.0 (12.0–3.0) | |

| Follow-up, years | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 16.77 (10.54) | 15.41 (8.17) | 17.66 (11.84) | 0.348a |

| Median (IQR) | 15.0 (25.0–8.0) | 15.50 (20.25–8.0) | 15.0 (27.0–8.0) | |

| IgG (mg/dl) | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 259.24 (210.37) | 254.92 (217.0) | 262.51 (208.18) | 0.827b |

| Median (IQR) | 200.0 (431.50–89.0) | 196.50 (377.50–88.50) | 226.0 (437.50–89.0) | |

| IgA (mg/dl) | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 17.08 (21.46) | 24.35 (27.61) | 11.57 (13.23) | 0.071*,b |

| Median (IQR) | 8.0 (29.0–4.0) | 11.50 (30.0–4.25) | 6.0 (17.50–1.50) | |

| IgM (mg/dl) | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 38.08 (47.15) | 48.22 (61.25) | 30.68 (32.38) | 0.311b |

| Median (IQR) | 20.0 (41.75–8.50) | 25.0 (48.0–15.0) | 19.0 (41.0–6.50) | |

| IgE (IU/mL) | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 7.51 (17.30) | 14.32 (25.59) | 3.23 (6.55) | 0.132b |

| Median (IQR) | 1.0 (2.75–1.0) | 1.0 (22.50–0.65) | 19.0 (41.0–6.50) | |

| Lymphocyte, cell/mL | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 2681.88 (1525.39) | 2357.33 (1542.39) | 2900.95 (1493.18) | 0.058*,b |

| Median (IQR) | 2200.0 (3600.0–1600.0) | 2000.0 (2662.0–1400.0) | 2601.0 (3895.0–1925.0) | |

| CD3+lymphocytes, cell/mL | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 74.36 (11.72) | 72.35 (12.93) | 75.80 (11.32) | 0.264a |

| Median (IQR) | 75.0 (83.0–66.25) | 72.30 (79.50–62.70) | 77.60 (85.0–67.65) | |

| CD4+T cells, cell/mL | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 27.54 (12.62) | 24.53 (12.93) | 29.75 (12.10) | 0.117a |

| Median (IQR) | 26.0 (35.0–18.0) | 23.0 (31.50–14.50) | 28.0 (38.30–21.25) | |

| CD8+T cells, cell/mL | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 43.30 (16.02) | 42.29 (16.43) | 44.05 (15.92) | 0.682a |

| Median (IQR) | 43.0 (55.60–31.0) | 42.0 (54.80–27.60) | 43.35 (56.25–32.45) | |

| CD19+lymphocytes, cell/mL | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 9.55 (8.52) | 10.56 (11.07) | 8.81 (6.14) | 0.981b |

| Median (IQR) | 8.0 (13.10–3.64) | 8.15 (13.65–2.03) | 7.30 (12.39–4.60) | |

Ig, immunoglobulins; CVID, common variable immune deficiency.

Note. For age, delay diagnosis and Ig levels, the median is shown [with 25th and 75th percentiles]. N, count.

The first presentation of CVID patients in this cohort. Infection, chronic diarrhoea, autoimmunity, and lymphoproliferative disorders were the most frequent first presentations seen in 71 CVID patients, respectively. In one patient, non-immunological neurological symptoms were the first presentation.

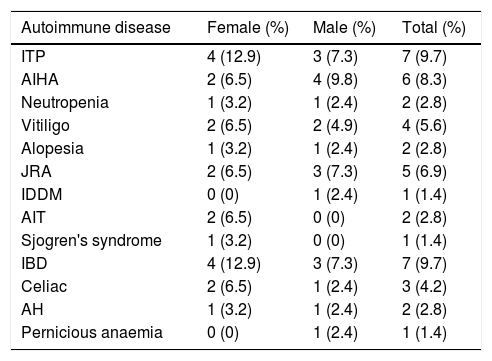

In our study, the most frequently seen autoimmune manifestations were autoimmune cytopenias and autoimmune gastrointestinal diseases (Table 2). The prevalence of autoimmune disease was 14 out of 31 (45.2%) in female patients and 15 out of 41 (36.6%) in male patients. Although autoimmunity seemed to be more common in females, the difference between male and female patients was not significant (p=0.463). Consanguinity was found among 43 of the CVID patients, 20 patients (46.5%) of whom had a manifestation of autoimmunity.

The frequency of various types of autoimmune diseases in CVID patients.

| Autoimmune disease | Female (%) | Male (%) | Total (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| ITP | 4 (12.9) | 3 (7.3) | 7 (9.7) |

| AIHA | 2 (6.5) | 4 (9.8) | 6 (8.3) |

| Neutropenia | 1 (3.2) | 1 (2.4) | 2 (2.8) |

| Vitiligo | 2 (6.5) | 2 (4.9) | 4 (5.6) |

| Alopesia | 1 (3.2) | 1 (2.4) | 2 (2.8) |

| JRA | 2 (6.5) | 3 (7.3) | 5 (6.9) |

| IDDM | 0 (0) | 1 (2.4) | 1 (1.4) |

| AIT | 2 (6.5) | 0 (0) | 2 (2.8) |

| Sjogren's syndrome | 1 (3.2) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.4) |

| IBD | 4 (12.9) | 3 (7.3) | 7 (9.7) |

| Celiac | 2 (6.5) | 1 (2.4) | 3 (4.2) |

| AH | 1 (3.2) | 1 (2.4) | 2 (2.8) |

| Pernicious anaemia | 0 (0) | 1 (2.4) | 1 (1.4) |

ITP, idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura; AIHA, autoimmune haemolytic anaemia; JRA, juvenile rheumatoid arthritis; IDDM, insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus; AIT, autoimmune thyroiditis; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; AH, autoimmune hepatitis.

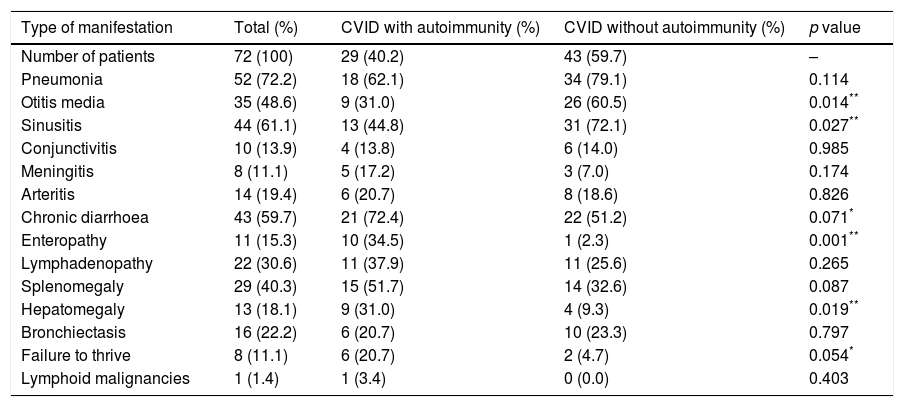

Upper and lower respiratory tract infections were more common in CVID patients without autoimmunity than patients with autoimmunity, whereas chronic diarrhoea, enteropathy, failure to thrive and organomegaly were more common in those with autoimmune complications (Table 3). A significant association was detected between the autoimmunity and presence of hepatomegaly and splenomegaly (p=0.019 and p=0.087, respectively). Our findings showed that there is an association between splenomegaly and autoimmune cytopenias (p=0.008). There was also a significant association between a history of enteropathy and the incidence of gastrointestinal autoimmune diseases (p=0.001). Moreover, there was a significant association between a history of septic arthritis and juvenile rheumatoid arthritis (p=0.001).

Comparison of immune-related clinical manifestations between CVID patients with autoimmunity vs. CVID patients without autoimmunity.

| Type of manifestation | Total (%) | CVID with autoimmunity (%) | CVID without autoimmunity (%) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 72 (100) | 29 (40.2) | 43 (59.7) | – |

| Pneumonia | 52 (72.2) | 18 (62.1) | 34 (79.1) | 0.114 |

| Otitis media | 35 (48.6) | 9 (31.0) | 26 (60.5) | 0.014** |

| Sinusitis | 44 (61.1) | 13 (44.8) | 31 (72.1) | 0.027** |

| Conjunctivitis | 10 (13.9) | 4 (13.8) | 6 (14.0) | 0.985 |

| Meningitis | 8 (11.1) | 5 (17.2) | 3 (7.0) | 0.174 |

| Arteritis | 14 (19.4) | 6 (20.7) | 8 (18.6) | 0.826 |

| Chronic diarrhoea | 43 (59.7) | 21 (72.4) | 22 (51.2) | 0.071* |

| Enteropathy | 11 (15.3) | 10 (34.5) | 1 (2.3) | 0.001** |

| Lymphadenopathy | 22 (30.6) | 11 (37.9) | 11 (25.6) | 0.265 |

| Splenomegaly | 29 (40.3) | 15 (51.7) | 14 (32.6) | 0.087 |

| Hepatomegaly | 13 (18.1) | 9 (31.0) | 4 (9.3) | 0.019** |

| Bronchiectasis | 16 (22.2) | 6 (20.7) | 10 (23.3) | 0.797 |

| Failure to thrive | 8 (11.1) | 6 (20.7) | 2 (4.7) | 0.054* |

| Lymphoid malignancies | 1 (1.4) | 1 (3.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0.403 |

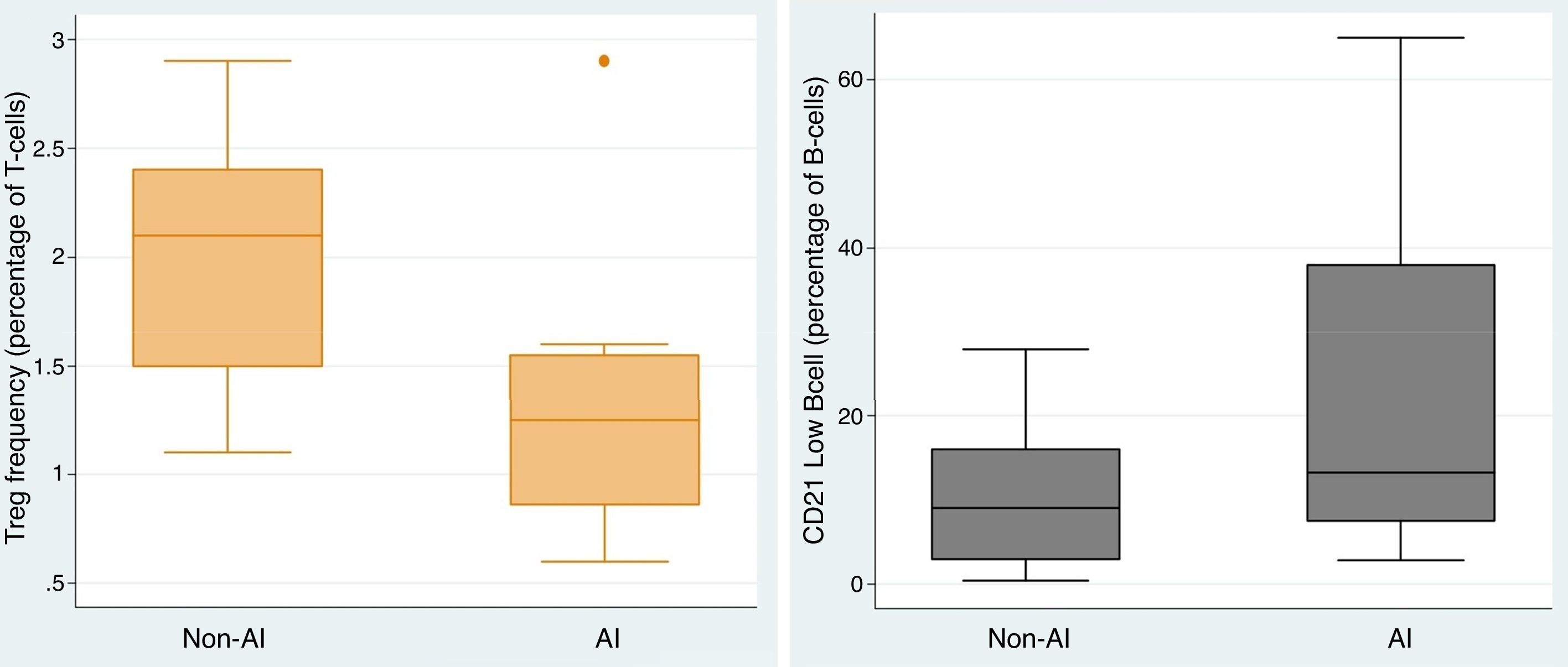

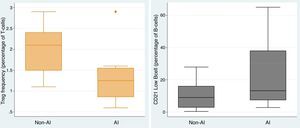

To elucidate the immunological heterogeneity of CVID patients according to whether or not they had developed autoimmunity, we studied anti-IgA, specific antibody response, autoantibodies and Tregs and B cell subsets in 51 (70.8%) of the CVID patients. 38.5% and 79.3% of the CVID patients presented a defect in Tregs and switched memory B-cell, respectively, whereas 69.0% presented an expansion of CD21low B cell. Among the CVID patients who had an abnormality in Tregs, switched memory and CD21low B cells, 80.0%, 52.2% and 55.0% were complicated by autoimmunity, respectively. Comparing the CVID patients with autoimmunity vs. CVID patients without autoimmunity, the frequency of Tregs (1.29 vs. 2.03, p=0.005) was lower in those with autoimmunity, whereas CD21low B cell was significantly higher (22.54 vs. 10.20, p=0.037) in them (Fig. 3). There was a negative correlation between the frequency of Tregs and the CD21low B cell population (r=−0.436).

CVID patients with autoimmune complications had a higher percentage of transitional and marginal zone B cells and a lower percentage of naive and non-class-switched memory B cells in comparison with CVID patients without autoimmunity; however, the difference was not significant. When comparing CVID patients who had multiple (two or three) autoimmune syndromes vs. CVID patients with one autoimmune syndrome, a higher level of CD3+ (79.85 vs. 68.98, p=0.049), CD4+ (35.24 vs. 19.74, p=0.006) and CD21low B cells (33.40 vs. 16.77, p=0.209) was observed in those experiencing multiple syndromes, whereas a lower number of Tregs (0.77 vs. 1.29, p=0.043) and naive B cells (49.40 vs. 65.17, p=0.092) was shown in them.

CVID patients with JRA were found to have higher levels of transitional B cells than patients with other autoimmune complications (25.75 vs. 1.26, p=0.002), whereas patients with gastrointestinal autoimmune diseases had higher levels of marginal zone B cells than others (13.33 vs. 1.39, p=0.002). In our study, 82.2% of CVID patients had defective specific antibody responses and 51.4% of them had autoimmunity. There was a positive correlation between the lack of specific antibody response and the lack of specific autoantibodies in the serum of CVID patients with autoimmunity (p=0.006, r=0.72). There was no significant relationship between anti-IgA antibody levels and the presence of autoimmunity. However, a positive correlation between anti-IgA antibody levels and the presence of specific autoantibodies was seen (r=0.683).

DiscussionAutoimmune manifestations have been reported to be more frequent among patients with CVID; it has been estimated that they affect approximately 30% (21–42%) of CVID patients.6,9,22,23 Our results showed that 40.3% of patients had a history of autoimmunity and similar to other studies, autoimmune cytopenias were the most frequent autoimmune complication. In our previous study, 26.9% of CVID patients had shown at least one autoimmune manifestation during the study period,21 however, the follow-up time was less than in the present study. Given the frequency and early onset in some patients, autoimmune disorders seem to be an integral part of CVID.

In our study, 18.0% of CVID patients had experienced the first episode of autoimmunity prior to the diagnosis of CVID; autoimmune cytopenias were the most common complication experienced by these patients. In a cohort study by Quinti et al.24 autoimmunity was found before the diagnosis of CVID in 17.4% of patients, and in 2.3% of these patients, autoimmunity was the only clinical manifestation of CVID. Moreover, two separate studies showed that 54%25 and 62%26 of CVID patients had the first episode of ITP or AIHA prior to the diagnosis of CVID. Therefore, autoimmunity may be an integral part of the disease in CVID patients with no considerable history of severe and recurrent infections. As in the present study, 7.0% of patients showed autoimmune complications as the first presentation of the disease. In our previous study among 85 CVID patients, seven cases (8%) suffered from autoimmune cytopenias, while CVID was presented with ITP in two patients (2.3%).27 In one study, Heeney et al.28 reported that four children with autoimmune cytopenias had low immunoglobulin levels that led to the diagnosis of CVID. Therefore, autoimmune disorders, especially autoimmune cytopenias, seem to be one of the first presentations of the CVID.29 It is important that the clinical immunologist and haematologist are aware of the main manifestations of CVID in order to reduce the diagnostic delay and establish timely immunoglobulin replacement therapy in these patients.

Previous studies reported that Treg frequencies as well as switched memory and CD21low B cells frequencies were altered in CVID patients and might account for the clinical manifestations including autoimmunity and splenomegaly.30–35 Immunologically, autoimmunity is associated with low numbers of Tregs and expanded CD21low B cells.36–38 Our results showed that in CVID patients with autoimmunity, the frequency of Tregs was significantly lower, whereas CD21low B cell frequency was significantly higher. In addition to Genre et al.,39 and our previous study in which CVID patients with autoimmunity were found to have a markedly reduced proportion of Tregs compared to those cases without autoimmune diseases, Arumugakani et al.11 demonstrated that CVID patients had significantly fewer Tregs than controls, and the low frequency of Tregs was associated with the expansion of CD21low B cells. These data are consistent with our findings regarding the negative correlation between the frequency of Tregs and CD21low B cell population in CVID patients with autoimmunity. This finding supports the previous findings and thus strengthens their validity. Moreover, it contributes to our understanding of the pathogenesis of CVID and is potentially valuable in the clinical management and treatment of patients.

Similar to the previous studies,36,40 our result showed that decreased numbers of switched memory B cells in CVID is associated with autoimmunity. Moreover, for the first time, we have evaluated other B cell subsets including naive, marginal zone-like, non-switched memory, and transitional B cell in CVID patients with and without autoimmune complications. We found that CVID patients with autoimmune complications have a higher percentage of transitional and marginal zone B cells and a lower percentage of naive and non-class-switched memory B cells in comparison with CVID patients without autoimmunity, although the difference was not significant. No study has further examined these B cell subsets in CVID patients, therefore no comparison could be drawn between the results. However, Dörner et al.41 reported that in systemic lupus erythematosus patients, both transitional B cells and naive B cells are greatly expanded. Moreover, Bugatti et al.42 reported an increased frequency of naive B cells in patients with RA. In our study, CVID patients with JRA had higher levels of transitional B cells than patients with other autoimmune complications, whereas patients with gastrointestinal autoimmune diseases had higher levels of marginal zone B cells than others.

In addition, impaired terminal B-cell differentiation into memory B cells and plasma cells were matched by hypogammaglobulinaemia and the lack of specific antibody response in CVID.19 In our study, 82.2% of CVID patients had defective specific antibody response and 51.4% of them had autoimmunity, but in most patients, the serum level of specific autoantibodies associated with their autoimmune disorder was considered negative. In one study, Pituch-Noworolska et al.43 evaluated the occurrence of autoantibodies for gastrointestinal autoimmune diseases in children with CVID. They reported that antibodies are produced despite impaired humoral immunity but their levels might be low, thus the lower limit of positive results is postulated. In another study, Milota et al.44 described two patients with a combination of IDDM and CVID with a serious antibody production impairment. IDDM-specific insulin autoantibodies and autoantibodies to glutamic acid decarboxylase and tyrosine phosphatase islet antigen type-2 were not detected in these patients at the time of diagnosis or during the course of the disease. Our result is in consistence with other studies, having shown that the levels of specific autoantibodies in the serum of CVID patients are often lower than in patients without CVID, therefore the lower limit of autoantibodies should be considered as significant for establishing the diagnosis of autoimmune diseases in CVID.45 Finally, physicians should be alert due to the weaker production or absence of antibodies, and a different histological pattern might be observed due to the lack of plasma cells in CVID biopsies.

Ethical disclosuresConfidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work centre on the publication of patient data and that all the patients included in the study have received sufficient information and have given their informed consent in writing to participate in this study.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained the informed consent of the patients and/or subjects mentioned in the article. The author for correspondence is in possession of this document.

Protection of human subjects and animals in researchThe authors declare that the procedures followed were in accordance with the regulations of the responsible Clinical Research Ethics Committee and in accordance with those of the World Medical Association and the Helsinki Declaration.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

This work was supported by vice chancellor for research, Tehran University of Medical Sciences under Grant No. 28966 and 29492.