Ataxia telangiectasia (A-T) is a genetic disorder caused by the homozygous mutation of the A-T mutated gene. It is frequently associated with variable degrees of cellular and humoral immunodeficiency. However, the immune defects in A-T patients are not well characterized. To the best of our knowledge, no studies have focused on the major lymphocyte subpopulations and recent thymic emigrants of A-T patients in comparison with age-matched healthy controls.

MethodsFollowing the European Society for Immunodeficiencies criteria, 17 patients diagnosed with A-The, and 12 age-matched healthy children were assigned to the study. Both patients and healthy controls were grouped as 1–5, 6–10, 11–15, and 15+ years. By using a flow cytometer, major lymphocyte subpopulations and CD4+CD45RA+CD31+ recent thymic emigrants were determined as percentage and absolute cell numbers and compared.

ResultsNo significant differences in all lymphocyte subpopulations were observed between the age groups of A-T patients. Compared to the healthy controls, there was a decrease in T cells, effector memory T4 cells, B cells, naïve B cells, naïve T4 cells, switched B cells, and recent thymic emigrants and an increase in active T8 cells and non-switched B cells in the percentage and absolute number of some cell populations in the A-T group.

ConclusionsThis study showed that effector functions in some cell lymphocyte populations were decreased in A-T patients.

Ataxia telangiectasia is a genetic disorder caused by the homozygous mutation of the A-T mutated (ATM) gene. It is frequently associated with variable degrees of cellular and humoral immunodeficiency. Immunodeficiency affects over half of all A-T patients and can contribute significantly to morbidity and mortality.1 However, the immune defects in A-T patients are not well characterized.2,3

To the best of our knowledge, no studies have focused on major lymphocyte subpopulations and recent thymic emigrants (RTE) of A-T patients in comparison with age-matched healthy controls. Therefore, this study aimed to clarify the relationship of age and major lymphocyte subpopulations and RTE of A-T patients that could have some effects on the clinical status of patients.

Patients and methodsPatients who were diagnosed with A-T at two medical centers – Ondokuz Mayıs University, Medical Faculty, Department of Pediatric Allergy and Immunology, and Inonu University Medical Faculty, Department of Pediatric Allergy and Immunology – between 2003 and 2013 were included in the study. A-T was diagnosed according to the European Society for Immunodeficiencies (ESID) criteria. Blood samples of these patients and age-matched healthy children were taken between August and November 2013. Both patients and healthy children were grouped as 1–5, 6–10, 11–15, and 15+ years. All blood samples were evaluated for absolute lymphocyte counts using an Abbot blood counter (Cell Dyn Emerald USA). By using flow cytometry, major lymphocyte subpopulations and CD4+CD45RA+CD31+ RTE were determined as percentage and absolute cell numbers and compared in both groups.

Financial support for the immunological evaluation of A-T patients was provided by governmental health insurance. For healthy children, the stock of the Ondokuz Mayis University's Pediatric Immunology-Allergy Diagnostic and Research Laboratory was used.

Evaluation of lymphocyte subpopulations by flow cytometryA total of 3cc peripheral venous blood was collected from each subject into ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) tubes. 100μL blood was added to the tubes and then incubated with a 10μL panel of conjugated antibodies CD45, CD3, CD4, CD8, CD19, CD45RA, CD31, CD56, HLA-DR, CD62L, CD27, and IgD (BD Biosciences, Heidelberg, Germany) for 20min at room temperature away from light. Then, samples were lysed by incubating in FACS lysing solution for 15min. Cells stained with isotypic controls for IgG1-FITC or PE were used as negative controls. After appropriate gating with lymphocytes, the lymphocyte populations were determined. The cytometer was set to acquire 10,000 events. Data were processed using CELL Quest software program (Becton Dickinson). These analyses were conducted for all subjects and were all performed by the same well-trained operator, who was unaware of the patients and healthy children. Based on the absolute lymphocyte counts, the absolute numbers of the lymphocyte subpopulations and RTE were proportioned as the number of cells per 1mL of whole blood.

Statistical analysisThe results were expressed as median (min–max) values. Because the data of both groups did not show a normal distribution, Mann–Whitney U test and Kruskal–Wallis test were used to evaluate all the data. Correlation analysis was used to evaluate the relationship between the two groups.

Ethical disclosuresEthics committee approval was granted by decision no. OMU KAEK 2013/331 dated 11.07.2013 by the Ondokuz Mayis University's Ethics Committee of Medical Research.

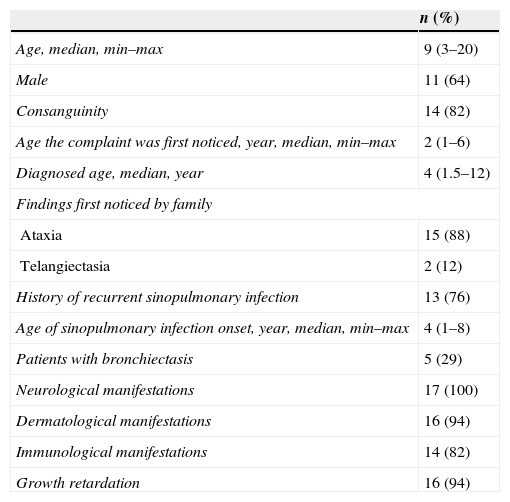

ResultsSeventeen A-T patients (11 male, 6 female, median: 9, min–max: 3–20 years) and 12 age-matched healthy children (4 male, 8 female, median: 10, min–max: 2–18 years) were assigned to this study. Neurological manifestations (e.g., ataxia, dysmetria), dermatological manifestations (e.g., telangiectasia, hypopigmentation), and immunological manifestations (e.g., hypogammaglobulinemia, lymphopenia) were seen in 17 (100%), 16 (94%), and 14 (82%) patients, respectively. Table 1 shows the demographic data of patients with ataxia telangiectasia.

Demographics of patients with ataxia telangiectasia.

| n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Age, median, min–max | 9 (3–20) |

| Male | 11 (64) |

| Consanguinity | 14 (82) |

| Age the complaint was first noticed, year, median, min–max | 2 (1–6) |

| Diagnosed age, median, year | 4 (1.5–12) |

| Findings first noticed by family | |

| Ataxia | 15 (88) |

| Telangiectasia | 2 (12) |

| History of recurrent sinopulmonary infection | 13 (76) |

| Age of sinopulmonary infection onset, year, median, min–max | 4 (1–8) |

| Patients with bronchiectasis | 5 (29) |

| Neurological manifestations | 17 (100) |

| Dermatological manifestations | 16 (94) |

| Immunological manifestations | 14 (82) |

| Growth retardation | 16 (94) |

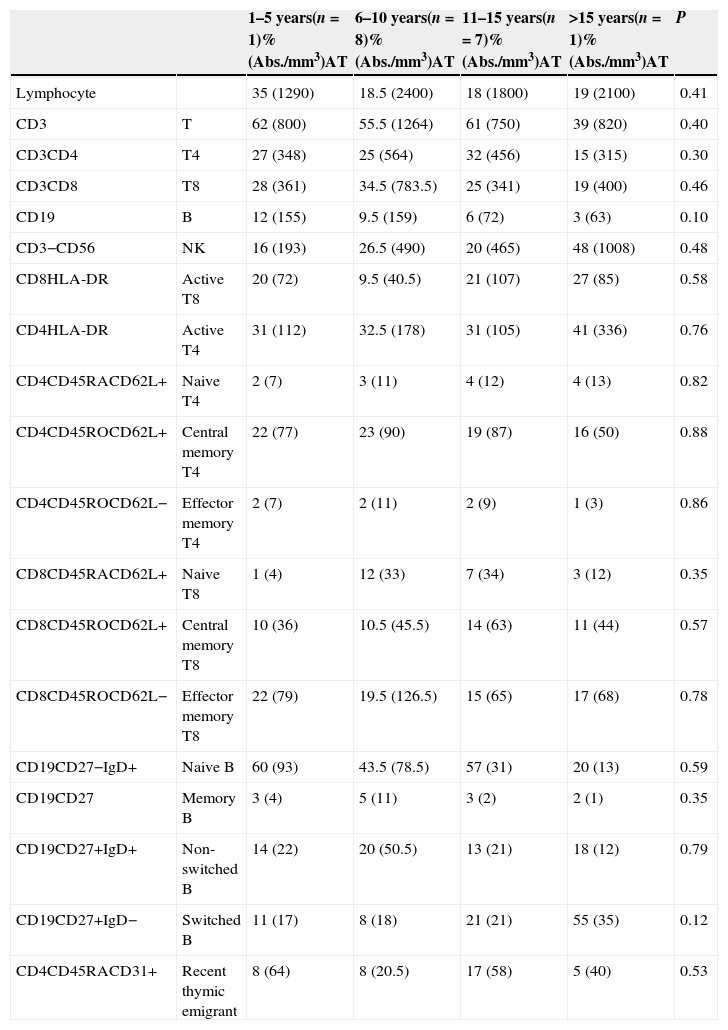

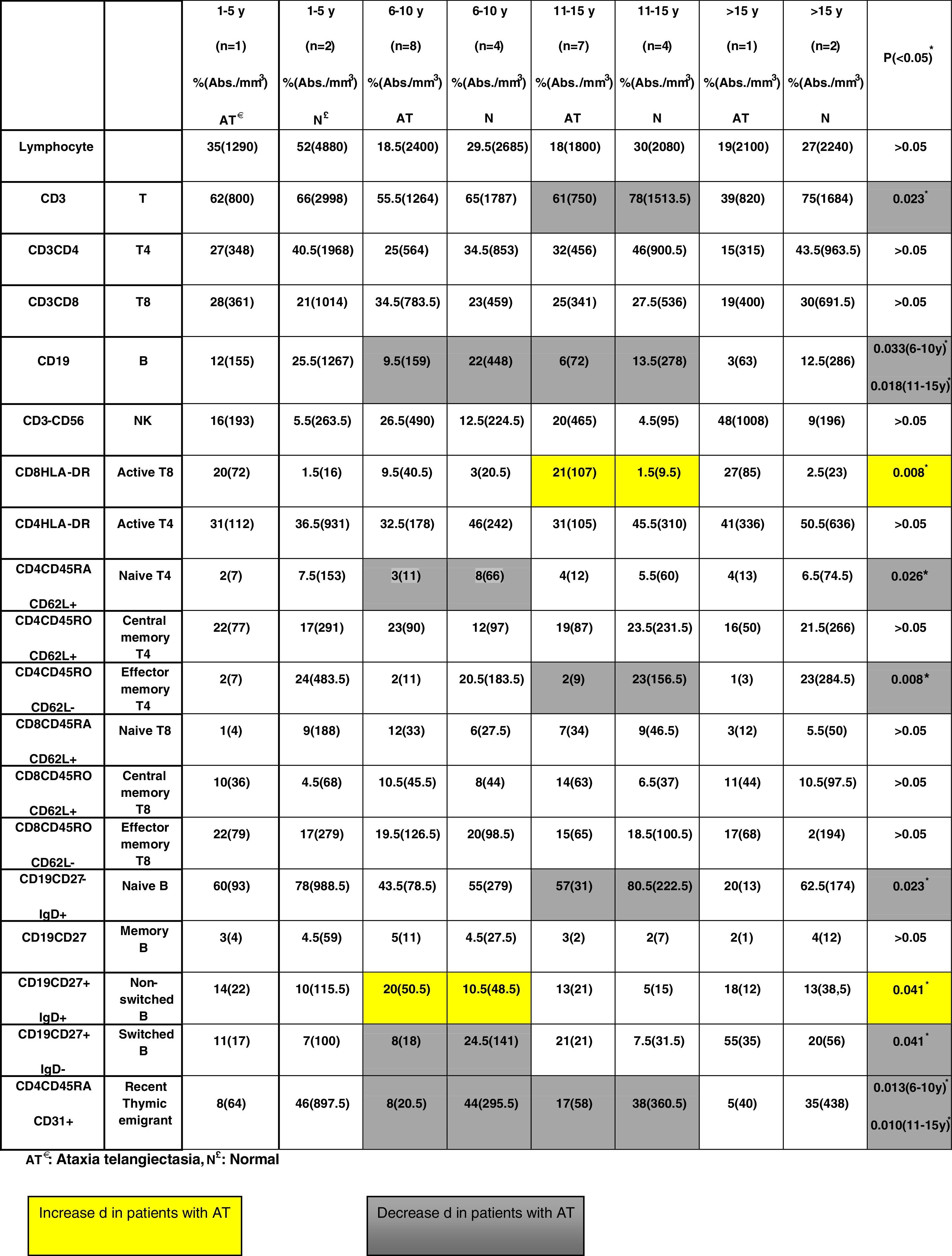

No significant differences regarding all lymphocyte subpopulations were observed between the age groups of A-T patients (Table 2). Compared to the healthy children, there was a decrease in the percentage and absolute number of some cell populations in the A-T group as follows: T cells (in 11–15 years group, p=0.023), effector memory T4 cells (in 11–15 years group, p=0.08), B cells (in 6–10 and 11–15 years groups, p=0.033 and p=0.018, respectively), naïve B cells (in 11–15 years group, p=0.023), naïve T4 cells (in 6–10 years group, p=0.026), switched B cells (in 6–10 years group, p=0.041), and RTE (in 6–10 and 11–15 years group, p=0.013 and p=0.010, respectively).

Major lymphocyte subpopulations of patients with ataxia telangiectasia according to age groups.

| 1–5 years(n=1)%(Abs./mm3)AT | 6–10 years(n=8)%(Abs./mm3)AT | 11–15 years(n=7)%(Abs./mm3)AT | >15 years(n=1)%(Abs./mm3)AT | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lymphocyte | 35 (1290) | 18.5 (2400) | 18 (1800) | 19 (2100) | 0.41 | |

| CD3 | T | 62 (800) | 55.5 (1264) | 61 (750) | 39 (820) | 0.40 |

| CD3CD4 | T4 | 27 (348) | 25 (564) | 32 (456) | 15 (315) | 0.30 |

| CD3CD8 | T8 | 28 (361) | 34.5 (783.5) | 25 (341) | 19 (400) | 0.46 |

| CD19 | B | 12 (155) | 9.5 (159) | 6 (72) | 3 (63) | 0.10 |

| CD3−CD56 | NK | 16 (193) | 26.5 (490) | 20 (465) | 48 (1008) | 0.48 |

| CD8HLA-DR | Active T8 | 20 (72) | 9.5 (40.5) | 21 (107) | 27 (85) | 0.58 |

| CD4HLA-DR | Active T4 | 31 (112) | 32.5 (178) | 31 (105) | 41 (336) | 0.76 |

| CD4CD45RACD62L+ | Naive T4 | 2 (7) | 3 (11) | 4 (12) | 4 (13) | 0.82 |

| CD4CD45ROCD62L+ | Central memory T4 | 22 (77) | 23 (90) | 19 (87) | 16 (50) | 0.88 |

| CD4CD45ROCD62L− | Effector memory T4 | 2 (7) | 2 (11) | 2 (9) | 1 (3) | 0.86 |

| CD8CD45RACD62L+ | Naive T8 | 1 (4) | 12 (33) | 7 (34) | 3 (12) | 0.35 |

| CD8CD45ROCD62L+ | Central memory T8 | 10 (36) | 10.5 (45.5) | 14 (63) | 11 (44) | 0.57 |

| CD8CD45ROCD62L− | Effector memory T8 | 22 (79) | 19.5 (126.5) | 15 (65) | 17 (68) | 0.78 |

| CD19CD27−IgD+ | Naive B | 60 (93) | 43.5 (78.5) | 57 (31) | 20 (13) | 0.59 |

| CD19CD27 | Memory B | 3 (4) | 5 (11) | 3 (2) | 2 (1) | 0.35 |

| CD19CD27+IgD+ | Non-switched B | 14 (22) | 20 (50.5) | 13 (21) | 18 (12) | 0.79 |

| CD19CD27+IgD− | Switched B | 11 (17) | 8 (18) | 21 (21) | 55 (35) | 0.12 |

| CD4CD45RACD31+ | Recent thymic emigrant | 8 (64) | 8 (20.5) | 17 (58) | 5 (40) | 0.53 |

AT: ataxia telangiectasia.

Compared to the healthy children, there was an increase in the percentage and absolute number of some cell populations in the A-T group as follows: active T8 cells (in 11–15 years group, p=0.08) and non-switched B cells (in 6–10 years group, p=0.041) (Table 3).

DiscussionIn this study, we evaluated the lymphocyte subpopulations and RTE of A-T patients and compared them with those of age-matched healthy children to understand whether there is any change or deterioration with age. There were no significant differences regarding all lymphocyte subpopulations between the age groups of A-T patients. However, compared to the healthy controls, there was a decrease in the percentage and absolute number of T cells, effector memory T4 cells, B cells, naïve B cells, naïve T4 cells, switched B cells, and RTE, and an increase in active T8 cells and non-switched B cells. The decreased effector and thymic emigrant (naïve)-type cell numbers might suggest that the developmental defects of the thymus in A-T patients should be related to this T and B cell status.

Carney et al. investigated the effect of A-T and age on the proportions of major lymphocyte subsets and their pattern of CD95 expression in relation to IL-7 levels in 15 A-T patients. They also analyzed the sensitivity of T cells from four A-T patients to CD95-mediated apoptosis using TUNEL and caspase-activation assays. Their results confirmed lymphopenia and a deficiency in naïve T and B cells in A-T patients. In contrast to the controls, the proportions of naïve and memory T and B cell subsets in A-T patients did not vary in relation to age. Their findings showed that the immunodeficiency in A-T patients is not progressive.2

Giovanetti et al. showed that the T-cell receptor (TCR) variable β (BV)-chain repertoire of nine A-T patients was restricted by diffuse expansions of some variable genes prevalently occurring within the CD4 subset and clustering to certain TCRBV genes. They concluded that ATM mutation limits the generation of a wide repertoire of normally functioning T and B cells.4

Staples et al. retrospectively reviewed 80 consecutive A-T patients for clinical history, immunological findings, ATM enzyme activity, and ATM mutation type. Of these, 61 patients had mutations resulting in complete loss of ATM kinase activity (group A), and 19 patients had leaky splice or missense mutations resulting in residual kinase activity (group B). A comparison of group A and group B patients showed that 25 of 46 patients had undetectable/low immunoglobulin A levels compared with none of 19 patients; T cell lymphopenia was found in 28 of 56 patients compared with 1 of 18 patients; and B cell lymphopenia was found in 35 of 55 patients compared with 4 of 18 patients. They concluded that A-T patients with no ATM kinase activity had a markedly more severe immunological phenotype than those expressing low levels of ATM activity.3

Immunophenotyping of peripheral blood lymphocyte subpopulations is essential for the diagnosis and follow-up of children with immunodeficiencies. Lavin et al. reported that faulty development of the thymus is highly characteristic of A-T, and some abnormalities appear to reflect a developmental defect rather than atrophy of the thymus.1 CD31+CD45RA+RO− lymphocytes RTE contain high numbers of T cell receptor circle (TREC)-bearing T cells, and CD31 is an appropriate marker to monitor TREC-rich lymphocytes.5 Then, lymphocyte subpopulations and RTE might be important to understand the etiopathogenesis of immunodeficiency in A-T.

Only three studies have focused on the lymphocyte subpopulations of A-T patients. Schubert et al. found that naïve T4 and T8 T cells were decreased but NK cells were increased.6 Carney et al. confirmed lymphopenia and a deficiency in naïve T and B cells in A-T patients. Their findings showed that the immunodeficiency in A-T patients is not progressive.2 In a longitudinal study, Chopra et al. found no deterioration in lymphocyte subpopulations.7 The present study's findings support these studies. However, the present study, unlike the abovementioned ones, evaluated the central and memory T4–T8 cells, memory and switched B cells, and RTE; furthermore, it compared all of these with those of age-matched healthy children.

Unlike RTE, naïve CD31−CD45RA+CD4+ T cells are characterized by a drastically reduced TREC content and a restricted oligoclonal TCR repertoire. Although the age-related dynamics of CD31 expression on CD4+ T cells has not yet been satisfactorily investigated, RTE was rapidly adopted in clinical practice because it gives an idea of the T cell function.7 In the present study, the RTE values of A-T patients were significantly decreased compared to those of the age-matched healthy children. This should be related to developmental defects of the thymus.

In conclusion, this study showed that some effector lymphocyte populations and thymic emigrants were decreased. However, the study has an important limitation in terms of the patients and healthy population.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this investigation.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that no patient data appears in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appears in this article.