PIDs are a heterogeneous group of genetic illnesses, and delay in their diagnosis is thought to be caused by a lack of awareness among physicians concerning PIDs. The latter is what we aimed to evaluate in Brazil.

MethodsPhysicians working at general hospitals all over the country were asked to complete a 14-item questionnaire. One of the questions described 25 clinical situations that could be associated with PIDs and a score was created based on percentages of appropriate answers.

ResultsA total of 4026 physicians participated in the study: 1628 paediatricians (40.4%), 1436 clinicians (35.7%), and 962 surgeons (23.9%). About 67% of the physicians had learned about PIDs in medical school or residency training, 84.6% evaluated patients who frequently took antibiotics, but only 40.3% of them participated in the immunological evaluation of these patients. Seventy-seven percent of the participating physicians were not familiar with the warning signs for PIDs. The mean score of correct answers for the 25 clinical situations was 48.08% (±16.06). Only 18.3% of the paediatricians, 7.4% of the clinicians, and 5.8% of the surgeons answered at least 2/3 of these situations appropriately.

ConclusionsThere is a lack of medical awareness concerning PIDs, even among paediatricians, who have been targeted with PID educational programmes in recent years in Brazil. An increase in awareness with regard to these disorders within the medical community is an important step towards improving recognition and treatment of PIDs.

PIDs encompass more than 200 genetic illnesses, predispose patients to infections, allergy, and autoimmune and malignant manifestations and are caused by immune system defects.1 Individual PIDs are considered rare diseases, while as a group, the estimated frequency ranges from 1:2000 to 1:10,000.2,3 However, many of these diseases have not yet been completely described.4

Over the last few decades, advances in immune system studies have allowed for a greater understanding of PID physiopathology, which has enabled greater diagnostic precision as well as recommendations of new therapeutic strategies.5 On the other hand, the great diversity of clinical and genetic defects makes recognition and diagnosis of patients with PID a challenge.6

Severe defects are easily recognisable, but there are cases in which PID is diagnosed only when the patient has been hospitalised one or more times and may already present permanent damage.7,8

Lack of awareness among physicians concerning PIDs is reported in many countries to be the probable cause of delay in diagnosis and undiagnosed PIDs, which are generally not included in the differential diagnoses of potentially affected patients.9–11

There are limited published data about physicians’ awareness concerning PIDs and most of them involved only paediatricians.12–15

The aim of this study is to evaluate physicians’ awareness concerning PIDs in Brazil.

MethodsThe study was approved by the Clinical Research and Ethics Committee of the Federal University of São Paulo – UNIFESP.

The study was cross-sectional and was conducted in general hospitals (public and private) in 27 cities throughout the country between July 2008 and January 2010. Hospitals were chosen taking into consideration the availability of medical, surgical and paediatric services as well as easy accessibility to researchers, given the country's large dimensions.

The sample was a convenience sampling. Considering that in 2009, there were 331,117 physicians active in Brazil,16 we needed approximately 3300 in order to reach at least 1% of physicians in the country.

The criteria to include a participating doctor were working at one of the previously selected hospitals and signing an informed consent.

Physicians working at multiple hospitals were asked to complete the questionnaire only once. The instrument used for data collection was a questionnaire drafted by members of the Allergy, Immunology and Rheumatology Division of the Paediatrics Department of the Federal University of São Paulo. It included a card with the 10 warning signs for PID compiled by the Jeffrey Modell Foundation (JMF)17 and adapted to Brazil by the Brazilian Group for Immunodeficiency (BRAGID).18 Participating physicians were asked to read the card prior to responding to the last question.

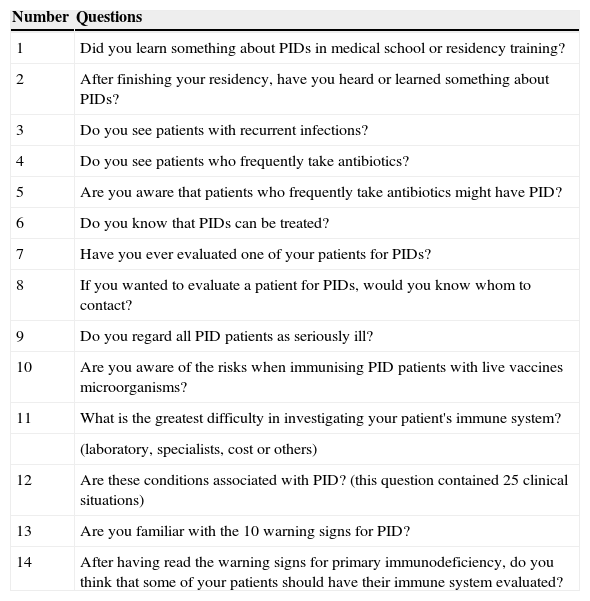

The first part of the questionnaire identified the participating doctor by means of name (optional), graduation year, specialty and practice type. The second part presented 14 questions about PID training and knowledge (Table 1).

Questions about PID training and knowledge.

| Number | Questions |

|---|---|

| 1 | Did you learn something about PIDs in medical school or residency training? |

| 2 | After finishing your residency, have you heard or learned something about PIDs? |

| 3 | Do you see patients with recurrent infections? |

| 4 | Do you see patients who frequently take antibiotics? |

| 5 | Are you aware that patients who frequently take antibiotics might have PID? |

| 6 | Do you know that PIDs can be treated? |

| 7 | Have you ever evaluated one of your patients for PIDs? |

| 8 | If you wanted to evaluate a patient for PIDs, would you know whom to contact? |

| 9 | Do you regard all PID patients as seriously ill? |

| 10 | Are you aware of the risks when immunising PID patients with live vaccines microorganisms? |

| 11 | What is the greatest difficulty in investigating your patient's immune system? |

| (laboratory, specialists, cost or others) | |

| 12 | Are these conditions associated with PID? (this question contained 25 clinical situations) |

| 13 | Are you familiar with the 10 warning signs for PID? |

| 14 | After having read the warning signs for primary immunodeficiency, do you think that some of your patients should have their immune system evaluated? |

The statistical analysis was carried out using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS Inc., Chicago, USA) version 17.0. For all data analyses, differences were considered statistically significant when p<0.05.

One of the questions described 25 clinical situations that could be associated with PIDs. A knowledge score (KS) was created based on the percentage of appropriate answers to those situations. The mean and standard deviation were measured for the scale variables. The Pearson's Chi-Square test was used in order to verify association between categorical variables while Student's t test was used to compare two groups for quantitative variables. According to the Central Limit Theorem it was not necessary to check data normality for Student's t test once the sample size was sufficiently large.

The analysis of variance (ANOVA) presupposes the data normality. Due to lack of normality in the data, which was checked by the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test, the non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis test was used to compare the medians among more than two groups.

Finally, Poisson's regression model was used to simultaneously determine which of the chosen variables influence the KS for PIDs. The model had the KS as a dependent variable. Explanatory variables were specialty, year of graduation, relationship with medical education institutions, practice type (public practice, private or both) and answer (yes or no) to certain selected questions (questions 3, 5, 7 and 13). A complete model was adjusted to include all independent variables. Then the non-significant variables were eliminated one by one (backwards method). Residual analysis was carried out for the final model (residual Pearson patronised and studentised and Cook's D).

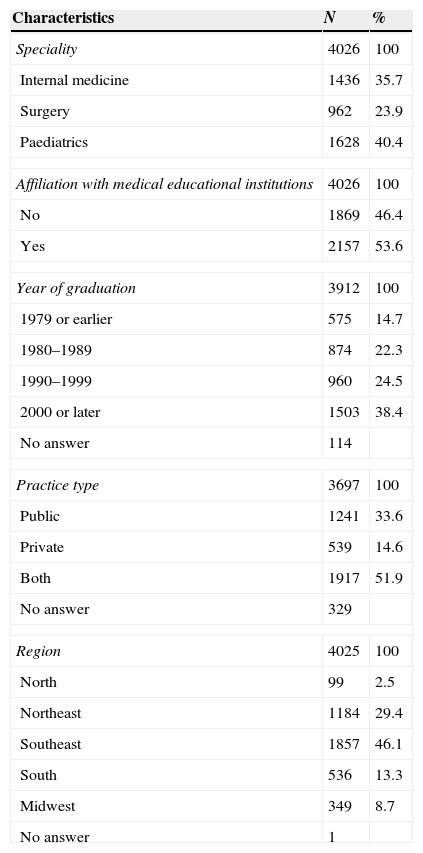

ResultsAll invited hospitals participated in the study. A total of 4041 physicians were invited to respond to the questionnaire and 4026 (99.6%) participated, with 1628 (40.4%) being paediatricians, 1436 internists (35.7%) and 962 surgeons (23.9%). Most of the participating physicians are affiliated with medical education institutions, had graduated from medical school after the year 2000, and have worked both in public and private services (Table 2).

Demographics of respondents.

| Characteristics | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Speciality | 4026 | 100 |

| Internal medicine | 1436 | 35.7 |

| Surgery | 962 | 23.9 |

| Paediatrics | 1628 | 40.4 |

| Affiliation with medical educational institutions | 4026 | 100 |

| No | 1869 | 46.4 |

| Yes | 2157 | 53.6 |

| Year of graduation | 3912 | 100 |

| 1979 or earlier | 575 | 14.7 |

| 1980–1989 | 874 | 22.3 |

| 1990–1999 | 960 | 24.5 |

| 2000 or later | 1503 | 38.4 |

| No answer | 114 | |

| Practice type | 3697 | 100 |

| Public | 1241 | 33.6 |

| Private | 539 | 14.6 |

| Both | 1917 | 51.9 |

| No answer | 329 | |

| Region | 4025 | 100 |

| North | 99 | 2.5 |

| Northeast | 1184 | 29.4 |

| Southeast | 1857 | 46.1 |

| South | 536 | 13.3 |

| Midwest | 349 | 8.7 |

| No answer | 1 | |

The paediatricians had the greatest contact with information about PIDs throughout residency training and after it (72.2% and 75.9%, respectively) compared to clinicians (66.2% and 47.3%, respectively) and surgeons (59.9% and 40.1%, respectively) (p<0.0001). More than 77% of the participating physicians have seen patients with recurrent infections, with a larger percentage of paediatricians (88.4%) than of internists (70.8%) and surgeons (68.1%) (p<0.0001).

Out of the total number of participants, 84.6% responded that they see patients who frequently use antibiotics (question 4), and 80.7% declared being aware that those patients might have PID (question 5), with a larger percentage of paediatricians (91.2%) than of clinicians (76.2%) and surgeons (69.4%) (p< 0.0001). However, when asked if they had ever evaluated a patient for PID, only 40.3% answered affirmatively, a percentage that rises to 48% among those who responded positively to questions 4 and 5 (p<0.0001).

Approximately 55% of internists and surgeons pointed to the fact that they were not acquainted with any immunologists and considered that as the greatest difficulty to evaluate a patient's immune system, whereas 57.4% of paediatricians pointed to deficiencies in laboratories. Cost limitation was singled out by 44% of all respondents.

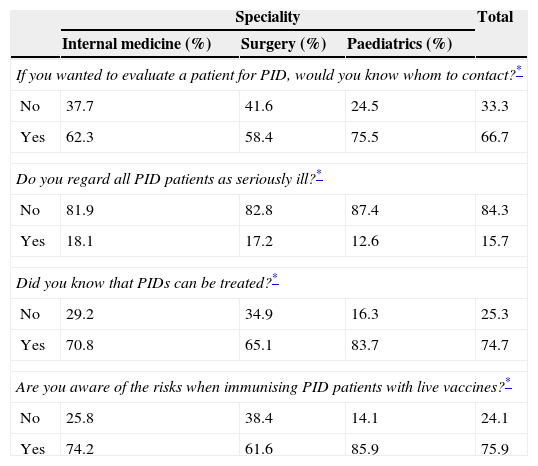

PID knowledgeThe answers to questions 6, 8–10 can be seen in Table 3. Distribution was not homogeneous among the specialities (p<0.05).

Physicians’ distribution according to speciality for questions 6, 8–10.

| Speciality | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Internal medicine (%) | Surgery (%) | Paediatrics (%) | ||

| If you wanted to evaluate a patient for PID, would you know whom to contact?* | ||||

| No | 37.7 | 41.6 | 24.5 | 33.3 |

| Yes | 62.3 | 58.4 | 75.5 | 66.7 |

| Do you regard all PID patients as seriously ill?* | ||||

| No | 81.9 | 82.8 | 87.4 | 84.3 |

| Yes | 18.1 | 17.2 | 12.6 | 15.7 |

| Did you know that PIDs can be treated?* | ||||

| No | 29.2 | 34.9 | 16.3 | 25.3 |

| Yes | 70.8 | 65.1 | 83.7 | 74.7 |

| Are you aware of the risks when immunising PID patients with live vaccines?* | ||||

| No | 25.8 | 38.4 | 14.1 | 24.1 |

| Yes | 74.2 | 61.6 | 85.9 | 75.9 |

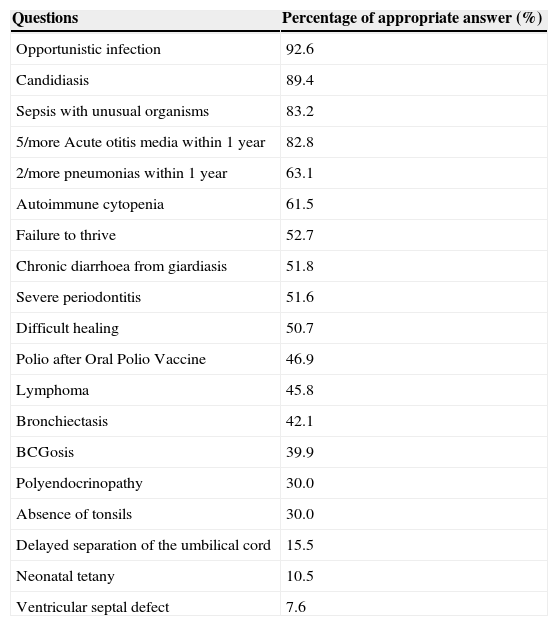

One of the questions described 25 clinical situations, out of which 19 could make a physician think of PID. The percentage of appropriate answers to each of those 19 situations can be seen in Table 4.

Percentage of appropriate answers to the clinical situations associated with PID.

| Questions | Percentage of appropriate answer (%) |

|---|---|

| Opportunistic infection | 92.6 |

| Candidiasis | 89.4 |

| Sepsis with unusual organisms | 83.2 |

| 5/more Acute otitis media within 1 year | 82.8 |

| 2/more pneumonias within 1 year | 63.1 |

| Autoimmune cytopenia | 61.5 |

| Failure to thrive | 52.7 |

| Chronic diarrhoea from giardiasis | 51.8 |

| Severe periodontitis | 51.6 |

| Difficult healing | 50.7 |

| Polio after Oral Polio Vaccine | 46.9 |

| Lymphoma | 45.8 |

| Bronchiectasis | 42.1 |

| BCGosis | 39.9 |

| Polyendocrinopathy | 30.0 |

| Absence of tonsils | 30.0 |

| Delayed separation of the umbilical cord | 15.5 |

| Neonatal tetany | 10.5 |

| Ventricular septal defect | 7.6 |

The KS elaborated in this study presented a mean of 48.09%, which equals 11 or 12 appropriate answers, and a median of 48%, with the minimum being 0% and the maximum 92%. According to specialities, the KS mean was greater among the paediatricians (57.71%), followed by internists (45.44%) and surgeons (42.47%) (p<0.0001).

Only 18.3% of the participants had a KS≥66.7% (11.4% for the paediatricians, 7.4% of internists and 5.8% for the surgeons).

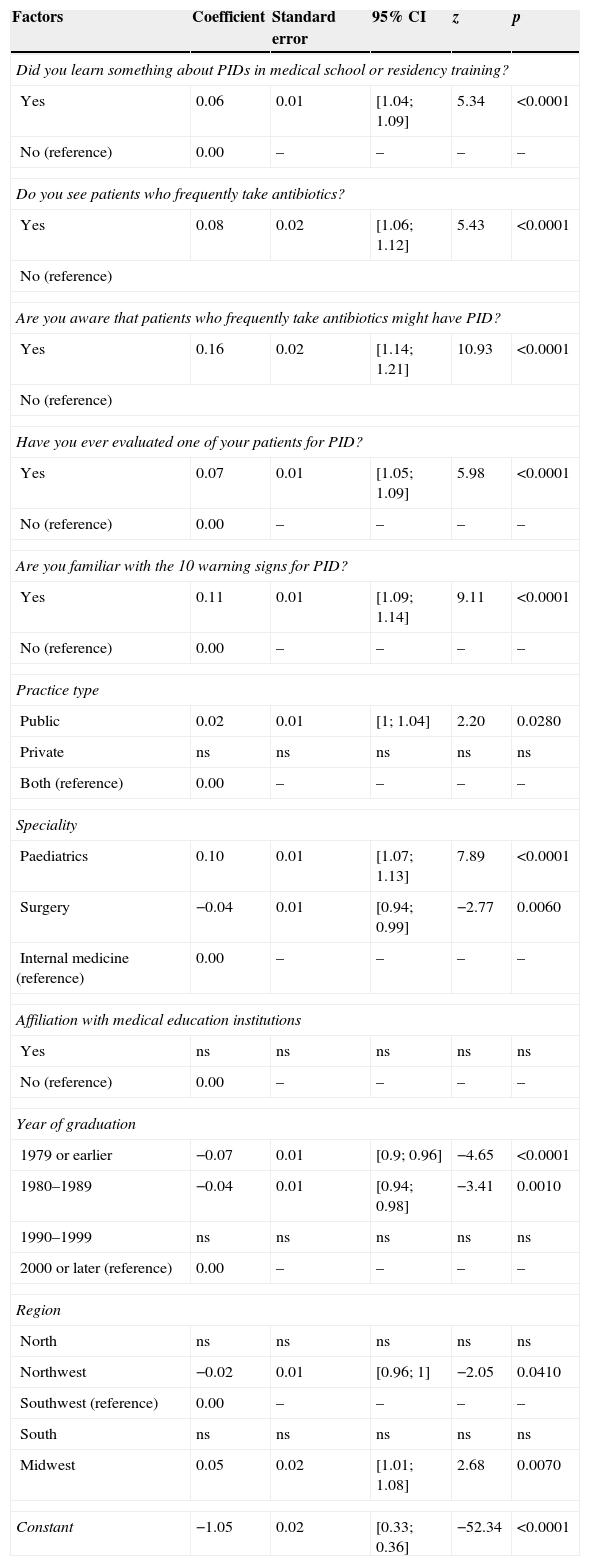

In Poisson's regression, the effect of selected independent variables on KS can be seen in Table 5.

Poisson's regression coefficients – final model.

| Factors | Coefficient | Standard error | 95% CI | z | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Did you learn something about PIDs in medical school or residency training? | |||||

| Yes | 0.06 | 0.01 | [1.04; 1.09] | 5.34 | <0.0001 |

| No (reference) | 0.00 | – | – | – | – |

| Do you see patients who frequently take antibiotics? | |||||

| Yes | 0.08 | 0.02 | [1.06; 1.12] | 5.43 | <0.0001 |

| No (reference) | |||||

| Are you aware that patients who frequently take antibiotics might have PID? | |||||

| Yes | 0.16 | 0.02 | [1.14; 1.21] | 10.93 | <0.0001 |

| No (reference) | |||||

| Have you ever evaluated one of your patients for PID? | |||||

| Yes | 0.07 | 0.01 | [1.05; 1.09] | 5.98 | <0.0001 |

| No (reference) | 0.00 | – | – | – | – |

| Are you familiar with the 10 warning signs for PID? | |||||

| Yes | 0.11 | 0.01 | [1.09; 1.14] | 9.11 | <0.0001 |

| No (reference) | 0.00 | – | – | – | – |

| Practice type | |||||

| Public | 0.02 | 0.01 | [1; 1.04] | 2.20 | 0.0280 |

| Private | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| Both (reference) | 0.00 | – | – | – | – |

| Speciality | |||||

| Paediatrics | 0.10 | 0.01 | [1.07; 1.13] | 7.89 | <0.0001 |

| Surgery | −0.04 | 0.01 | [0.94; 0.99] | −2.77 | 0.0060 |

| Internal medicine (reference) | 0.00 | – | – | – | – |

| Affiliation with medical education institutions | |||||

| Yes | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| No (reference) | 0.00 | – | – | – | – |

| Year of graduation | |||||

| 1979 or earlier | −0.07 | 0.01 | [0.9; 0.96] | −4.65 | <0.0001 |

| 1980–1989 | −0.04 | 0.01 | [0.94; 0.98] | −3.41 | 0.0010 |

| 1990–1999 | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| 2000 or later (reference) | 0.00 | – | – | – | – |

| Region | |||||

| North | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| Northwest | −0.02 | 0.01 | [0.96; 1] | −2.05 | 0.0410 |

| Southwest (reference) | 0.00 | – | – | – | – |

| South | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| Midwest | 0.05 | 0.02 | [1.01; 1.08] | 2.68 | 0.0070 |

| Constant | −1.05 | 0.02 | [0.33; 0.36] | −52.34 | <0.0001 |

ns – not significant.

CI 95% – confidence interval 95%.

Over the last decade, there have been major paradigm shifts in the field of PIDs in terms of genotypes, phenotypes, patients, and population levels.19 The complexities of immunodeficiencies are characterised by phenotypic heterogeneity, making recognition of some PIDs by physicians who are not specialists in the area more difficult.20 Significant advances have been made in diagnosis and management of PIDs, resulting in reduced rates of morbidity and mortality.21 However, clinicians in many countries are still confronted by a number of practical issues under-recognition, limited access to specialised diagnostic facilities, costly treatments, and lack of sufficient specialist centres dedicated to the care of this group of patients.11,22

About 70% of physicians had learned about PIDs in medical school or residency training, but 45% are not familiar with the warning signs for PIDs. Continuing education and training programmes are needed for paediatricians and general practitioners, as well as for specialists, in order to ensure that they can recognise the warning signs for PIDs, and particularly for those practicing in regions away from large cities.23 Physicians who are not experts in the diagnosis and treatment of PID may not recognise affected patients due to the diversity of immune defects and their respective clinical presentations.24,25 Although the great majority of the known PID disorders are present in infancy and childhood, some diseases will only be diagnosed in adulthood.26

Only 11.4% of participants answered 2/3 of the questions appropriately. Another questionnaire applied to paediatricians in Kuwait also showed a deficiency in PIDs knowledge, with only 26% of the participating paediatricians correctly answering 2/3 of the questions27 but a higher index was achieved by paediatricians in Arab Emirates.14 In our study, the factors associated to an increase in KS were being a paediatrician, having learned about PIDs in medical school or residency training, being aware that patients who frequently take antibiotics might have PIDs, having evaluated some patients for PIDs and being familiar with the PIDs warning signs. Most of these factors are related with medical education. The Jeffrey Modell Foundation has recently shown that physician education and public awareness might significantly impact the early diagnosis of PIDs.11 The 10 warning signs of PID are being promoted as a screening tool for PID. Recent studies have started a discussion based on the fact that the 10 warning signs do not take into account some clinical signs, such as autoimmune and malignant manifestations, that have been linked to PIDs after the great recent revolution in the understanding of these diseases.28,29 However, in our study we noticed that the physicians who were familiar with the warning signs had better knowledge of the clinical situations associated with PID which included autoimmune and malignant manifestations, and consequently had a better KS. Thus, it seems that despite the fact that the warning signs need to be revised due to expanding PID knowledge, they are still an important tool to improve awareness about PIDs.

Clinical manifestations such as infection by opportunistic or unusual organisms were associated with immunodeficiencies for over 80% of the physicians. These symptoms are more typical and usually seen in secondary immunodeficiency which facilitated recognition by physicians. On the other hand, only 39.9% of participants responded correctly to BCGosis, which is an important warning sign in Brazil since all newborns receive the BCG vaccine. A recent review of data showed that approximately 65% of Brazilian SCID patients presented with the BCG vaccine's side effects.30

Fewer than 20% of the physicians associated PIDs with delayed separation of the umbilical cord, which is characteristic of some phagocyte deficiencies. Neonatal tetany and ventricular septal defect can be associated with DiGeorge Syndrome, which is underdiagnosed in Brazil although the disease incidence is approximately 1:3000.31

Despite the fast developments in the field of PID, there is still a significant impact imposed on the health system by these disorders.32 In many cases, PIDs are usually detected only after the individual has experienced recurrent infections that may or may not have caused permanent organ damage. A review of data obtained from the Federal University of São Paulo, Brazil, showed that the mean delay in diagnosis of common variable immunodeficiency (CVID), which is the most frequent PID with clinical symptoms, was 6.7 years.33 Interestingly, delay in diagnosis also occurs in developed countries. In Finland, the diagnosis of CVID was delayed by 5 years in two-thirds of the patients and by 10 years in one-third of them.34 In the United Kingdom, a delay of 6.2 years decreased to 3.5 years after implementation of a government programme directed at early recognition and diagnosis of PIDs.35

Being the country with the largest population in Latin America, Brazil potentially has the largest number of patients with PIDs in the region. However, it is estimated that Brazil has around 2000 PID patients under treatment and that approximately 19,000 patients with PIDs are still waiting for diagnosis and proper management.9 Brazil has already registered 1000 patients in the online registry of the Latin American Group for Immunodeficiencies (LASID) (results available at http://imunodeficiencia.unicamp.br:8080/). The main problems that are thought to explain the misdiagnosis or late diagnosis are the lack of proper training of general practitioners and medical specialists, the difficulties in accessibility to screening tests, educational programmes, and treatment centres.36

The present study demonstrates that there is a deficiency in medical awareness about PIDs in Brazil, even among paediatricians, who have been targeted with PID educational programmes in recent years in Brazil. Educational efforts should not only focus on paediatricians, but should also include internists, surgeons and medical students. Ensuring timely diagnosis and optimal treatment is the fundamental issue faced by doctors dedicated to the care of PID patients.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Ethical disclosuresPatients’ data protectionConfidentiality of data. The authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Protection of human subjects and animals in researchThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this investigation.

This work was supported by the Jeffrey Modell Foundation and by the Brazilian Jeffrey Modell Centre. The authors thank Waleed Al-Herz for suggestions.