Asthma is a chronic inflammatory disease of airways with a high prevalence among children in pre-school ages. Considering controversial results in different studies about the effect of this disease on the indices of dental caries, the aim of this study was to compare dmft (decay, missing, filling teeth) situation in asthmatic and non-asthmatic 6–12-year-old children.

MethodsThis was a case-control study on 46 asthmatic and 47 non-asthmatic children aged 6–12 years. In asthmatic children, the severity of disease, type and dose of the administered inhalational drug, duration of drug consumption, times and technique of drug administration, and washing the mouth after drug consumption was assessed. The index of primary teeth decay or dmft, dental plaque and gingival inflammation were recorded in both groups. Data were analysed by SPSS (ver. 22) using Student's T-test, chi-square test and linear regression.

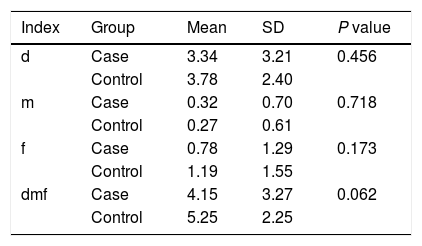

Findingsdmft in case and control groups was 5.25±2.25 and 4.15±3.27, respectively and the difference was not statistically significant (P=0.062). None of the variables related to asthma affected dmft (P>0.05).

ConclusionSuffering from asthma does not affect the risk of decay in primary teeth.

Asthma is a chronic inflammatory disease of airways that is triggered by various factors such as infections, domestic or occupational allergens, tobacco smoke, exercise and stress and some drugs. Asthma causes reversible narrowing and inflammation of airways and increased mucous secretions. In some chronic cases, fibrosis and irreversible changes may ensue. It is a periodic disorder with acute exacerbations interspersed by symptomless periods. The disease is determined by a triad of dyspnoea, cough and wheezing.1 According to the report of Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA), it is estimated that 300 million people suffer from this disease,1 and its prevalence is increasing worldwide.2 Entezari et al. showed that the prevalence of asthma symptoms in Iran is higher than the global report.3 The prevalence of asthma is higher among pre-school children than adults. One out of ten children suffer from asthma.4 Before puberty, the prevalence in males is twice that in females, although the prevalence after puberty is similar in both genders.5

Previous studies on the prevalence of dental caries in asthmatic children were controversial. Some studies showed that the risk of dental caries increased in asthmatic children,6–11 and that the prevalence of decay was higher among these children compared with healthy ones6,13; and that asthma significantly decreases salivary flow and PH and there is a positive association between the duration of disease and streptococcus mutans count in saliva.12 These studies considered asthma as a risk factor for dental caries. Although some other studies rejected this association and found that the prevalence of dental caries was not significantly different between asthmatic and healthy children,4,13,14 some studies showed that the prevalence of dental caries was lower in asthmatic patients (although not significant).15,16

Based on studies that consider asthma as a risk factor for dental caries, Drugs use in asthma, especially those consumed via inhalational route can cause mouth dryness which may predispose the individual to dental caries.4 β2-agonists, corticosteroids and sodium cromoglycates alone or in combination are used via inhalational route to control asthma. Repeated consumption of anti-asthma drugs, disease severity and combination therapy can significantly change the characteristics of saliva in asthmatic children.13 According to some of these studies, regardless of the drug type, the technique of drug consumption may also affect dental caries. If the patient is not aware of the correct method of using inhaler drugs, a larger amount of drug particles remain in the mouth, which may aggravate dental caries in these patients.17 Khalizadeh et al. showed a lower risk of dental caries in patients trained for the technique of consuming inhaler drug.18

Due to these controversies this study was designed to assess and compare dmft (decay-missing-filled teeth) index in asthmatic and non-asthmatic 6–12-year-old children in Yazd, Iran.

Materials and methodsIn this case-control study, 46 asthmatic and 47 healthy children entered the study. At first all parents were given accurate information about how we do the study and were assured that at any moment that they want they could exclude their children from the study and that we do not use any x-ray beam or harmful drugs in this study, their written informed consent was taken. The study was approved by the ethics committee of Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences, Yazd, Iran (code: 45637). The subjects in the case group were randomly selected from those referred to a private dental office in Yazd. Those children who suffered from asthma confirmed by an asthma-allergy subspecialist entered the study. Exclusion criteria were: mental retardation, chronic systemic disease, long-term antibiotic consumption, and respiratory diseases other than asthma. The children in the control group were randomly selected from those referring to the community – dentistry department in the dental school of Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences, Yazd, Iran for their routine dental examinations. The children in the control group were similar to the cases regarding demographic and socio-economic characteristics. Considering dental caries as a multifactorial disease affected by different factors such as salivary features, oral hygiene and nutrition, the subjects were randomly selected by a table of random digits in order to minimise the effect of these factors. Demographic data including age and gender and information about asthma (severity, duration, administered drug, times of daily drug consumption, drug dose, use of spacer, and washing mouth after drug consumption), and history of gastrointestinal reflux, adenoid hypertrophy, and allergic rhinitis were gathered and recorded by the examiner. Asthmatic children are classified according to GINA classification into intermittent and persistent (1). The children in this study suffered from persistent asthma with different disease severities, i.e. mild, moderate and severe and were treated for at least six months and maximum five years continuously and non-stop by corticosteroid inhalers including: budesonide/formoterol fumarate (160μg/4.5μg and 320μg/9μg), salmeterol/fluticasone propionate (25μg/125μg and 25μg/250mg), beclomethasone propionate monohydrate (50mg and 100mg), fluticasone propionate (125mg and 250mg). The children had used salbutamol in asthma attacks, but in the study only continuous use of corticosteroids was considered. In order to match the daily amount of consumed drug, dose×times of daily inhaler use was calculated and children were categorised as low, moderate and high regarding inhaler use according to GINA guidelines.

In this study, children were divided into three groups, i.e. high-risk, moderate-risk and low-risk, according to guidelines of American Academy of Paediatric Dentistry (AAPD) and Caries Risk Assessment Tool (CAT).19 During dental examination, necessary data about the objectives of the study was explained for the parents and an informed consent was obtained for each participant. Oral examination was performed by a dental student according to World Health Organisation (WHO) criteria in the sitting position, with appropriate lighting including looking into the mouth and use of tactile test by mouth mirror and tongue blade.20 Oral examination included assessment of dmft, presence of plaque (visible plaque or without plaque), gingival inflammation (exist or not exist), and mouth breathing. Clinical diagnosis of mouth breathing was done by assessment of night-time snoring, sleeping with open mouth and continuous or intermittent nasal congestion. Data were analysed by SPSS (ver. 22). Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used to assess the normal distribution of data. For comparing demographic variables between two groups, Student's T-test and chi square test were used. In order to assess the effect of asthma variables on dmft, linear regression was used. Level of significance was set at P<0.05.

ResultsIn the current study, 93 children were assessed: 46 children with asthma in the case group, 34 boys (73.9) and 12 girls (26.1) with mean age of 8.58±1.82 years, and 47 matched children in the control group, 21 boys (44.7) 26 girls (55.3) with mean age of 8.21±1.51 years. Indices of oral hygiene including times of tooth brushing, and using dental floss were not significantly different between the two groups (P=0.185 and P=0.982, respectively), so both groups were similar regarding oral hygiene. In total, 54.3% and 59.6% of the case and control groups had observable dental plaques and the difference was not statistically significant (P=0.611). dmft score was normally distributed (P=0.26). Using a scatter plot, residual values were plotted against the fitted values and the homogeneity of variances was assessed; two models were eventually selected from different presented models (Tables 2 and 3). In these two tables (Tables 2 and 3) standard deviation for coefficients were calculated and brought. T-test was done for checking the meaningfulness of variables coefficient in reported linear regression. (T) and P-values are expressed for each test (Table 1).

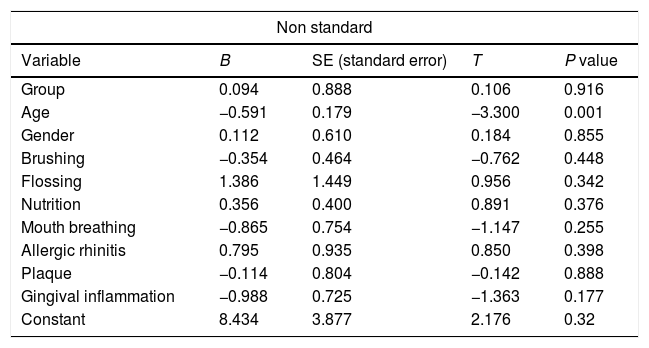

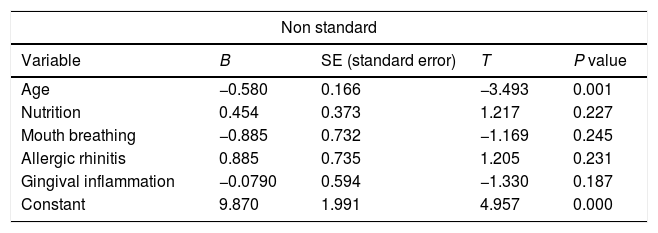

Backward linear regression showed that adjusted R2 was 0.099 in the first model (Table 2). This value was much lower than the value obtained in the second model (Table 3), so the second model which did not contain the group variable was selected. In the second model with adjusted R2=0.15, the effect of age, nutrition, mouth breathing, allergic rhinitis and gingival inflammation (exist or not exist) on dmft was assessed. Age was the only variable with a significant effect (P=0.001). This variable was negatively related to dmft. Age regression coefficient per dmft was −0.058, which means that each unit increase in age caused 0.58 unit decrease in dmft score (assuming that other variables were constant) (B=−0.058). Other variables such as nutrition, mouth breathing, allergic rhinitis and gingival inflammation were meaningless in this model. (Table 3)

The results of backward linear regression analysis in evaluation of effects of different variables on dmft in case and control groups.

| Non standard | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | B | SE (standard error) | T | P value |

| Group | 0.094 | 0.888 | 0.106 | 0.916 |

| Age | −0.591 | 0.179 | −3.300 | 0.001 |

| Gender | 0.112 | 0.610 | 0.184 | 0.855 |

| Brushing | −0.354 | 0.464 | −0.762 | 0.448 |

| Flossing | 1.386 | 1.449 | 0.956 | 0.342 |

| Nutrition | 0.356 | 0.400 | 0.891 | 0.376 |

| Mouth breathing | −0.865 | 0.754 | −1.147 | 0.255 |

| Allergic rhinitis | 0.795 | 0.935 | 0.850 | 0.398 |

| Plaque | −0.114 | 0.804 | −0.142 | 0.888 |

| Gingival inflammation | −0.988 | 0.725 | −1.363 | 0.177 |

| Constant | 8.434 | 3.877 | 2.176 | 0.32 |

The results of backward linear regression analysis in evaluation of effects of different variables on dmft in case and control groups.

| Non standard | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | B | SE (standard error) | T | P value |

| Age | −0.580 | 0.166 | −3.493 | 0.001 |

| Nutrition | 0.454 | 0.373 | 1.217 | 0.227 |

| Mouth breathing | −0.885 | 0.732 | −1.169 | 0.245 |

| Allergic rhinitis | 0.885 | 0.735 | 1.205 | 0.231 |

| Gingival inflammation | −0.0790 | 0.594 | −1.330 | 0.187 |

| Constant | 9.870 | 1.991 | 4.957 | 0.000 |

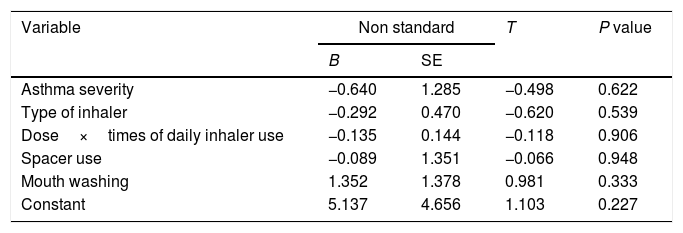

From Table 4 and linear regression test, the variables related to asthma such as asthma severity (P-value=0.622), type of inhaler (P-value=0.539), dose×times of daily inhaler use (P-value=0.906), using the spacer (P-value=0.948) and mouth washing after using spray (P-value=0.412) had no meaningful effect on dmft.

The results of backward linear regression analysis in evaluation of effects of different asthma related variables on dmft.

| Variable | Non standard | T | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | |||

| Asthma severity | −0.640 | 1.285 | −0.498 | 0.622 |

| Type of inhaler | −0.292 | 0.470 | −0.620 | 0.539 |

| Dose×times of daily inhaler use | −0.135 | 0.144 | −0.118 | 0.906 |

| Spacer use | −0.089 | 1.351 | −0.066 | 0.948 |

| Mouth washing | 1.352 | 1.378 | 0.981 | 0.333 |

| Constant | 5.137 | 4.656 | 1.103 | 0.227 |

In this study, the prevalence of caries in primary teeth was assessed in asthmatic and healthy 6–12-year-old children. In the asthmatics, disease severity, type and dose of the inhaler drug, duration of drug consumption, technique and times of inhaler use, and mouth washing after inhaler use were also assessed. There are different studies with controversial results on both primary and permanent teeth. The observed controversy is probably due to the design of the studies (mostly cross-sectional), small sample size, and difference in the consumed drug and severity of asthma. Finding a relationship between asthma and dental caries is difficult, because both diseases are chronic and multifactorial. The severity of asthma and administered drug may change in different stages of the disease which may affect the exact diagnosis of the disease in children.

The results of this study failed to show a significant difference between asthmatics and non-asthmatics regarding dmft. One reason for this finding is probably a similar level of oral hygiene in the case and control groups without a significant difference. Maupome et al. in a critical review of literature showed that asthma was not a risk factor for dental caries,21 because by observance of oral hygiene and training of the methods to control dental plaques, there will not be a difference between asthmatic and healthy children regarding dental decay. The results of some previous studies showed that DMFT/dmft (DMFT: caries index in permanent dentition system and dmft: caries index in primary dentition system, and in this study both systems were studied) was not significantly higher in asthmatics comparing the control group, which was in agreement with the results of the current study2,3,6,11,16,22,23; although some other studies in the same age groups found asthma as a risk factor for dental caries.11,15,24,25 Ghasempour et al. in 2005, in a study on both primary and permanent teeth, found a significant difference between asthmatic and non-asthmatic participants regarding DMFT in permanent teeth (2.27 in asthmatics vs. 0.8 in non-asthmatics), but they could not find a significant difference in primary teeth (3.53 in asthmatics vs. 3.22 in non-asthmatics). The results of the current study were consistent with the results of that study.26 Ersin et al., in a study in 2006, found a significant decrease in salivary flow and PH in asthmatic children.6 The Ehsani et al. study failed to find a significant difference between asthmatic and non-asthmatic children regarding dmft.4 This study assessed dental plaque, gingivitis, mouth breathing, dental caries, and count of streptococcus mutans and lactobacillus in the saliva as well.4 Markovic et al. also did not find a relationship between asthma and oral diseases; although they found that the dose of consumed corticosteroid inhaler affected primary teeth caries.16 Stensson et al. found opposite results. They showed that asthmatic 3–6-year-old children were at increased risk of caries than healthy children. Asthmatic children also had a higher frequency of haemorrhage due to gingivitis and mouth breathing inconsistent with the present study.14 Alaki et al. also showed that persistent use of anti-asthmatic drugs, severity of asthma and combination therapy significantly affect the characteristics of saliva in asthmatic children.7 In the current study, it was found that none of the variables related to asthma affect dmft indices in primary teeth. However, some previous studies showed that inhalational corticosteroids affect dental caries,12,27 but in the current study, we could not find any effect of corticosteroids on dental systems, which is probably due to the small sample size. Indeed, there was no significant relationship between the type and dose of inhaler, duration of treatment, and times of daily inhaler use and caries indices. Most asthmatic children were categorised in the moderate group regarding drug dose×times of inhaler use; i.e. dose of the consumed drug was similar among children with different severities of asthma. Boskabadi et al., in agreement with the results of the present study, could not find a relationship between caries indices and dose of the drug and times of daily inhaler use.10 Inconsistent with these findings, Mehta et al. and Backman et al. found a positive relationship between dental caries indices and duration of disease.13,28 A large amount of inhaled drugs remain in the mouth, and inhaled powder usually contains such carbohydrates as lactose which potentially can increase the probability of dental caries. Therefore, it is recommended that children wash their mouth with water after steroid inhalation.29 In this study, 80% of asthmatic children did not wash their mouth after inhaler use, which is probably due to lack awareness by children and their parents. According to the results of the current study, dmft index decreased by increasing age in both groups, which is due to loss of primary teeth and substitution by permanent teeth.

This study had some limitations. Our sample size was small due to time constraints, and also some children did not continue their treatment, so they were omitted from the study. Therefore, the results cannot be generalised to all asthmatic children in Yazd, Iran. It is recommended to design longitudinal studies with larger sample sizes on asthmatic children.

Conclusion: although this study had some limitations such as time constraints and follow-up limitations so we cannot generalise the results to all asthmatic children, the results showed that there is not a significant relationship between dental caries indices and asthma. Therefore, due to the present study asthma alone cannot increase the risk of dental caries

Ethical disclosuresConfidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work centre on the publication of patient data and that all the patients included in the study have received sufficient information and have given their informed consent in writing to participate in that study.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appears in this article.

Protection of human subjects and animals in researchThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this investigation.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflict of interest to declare.