It is considered that farm areas protect young patients from allergy and asthma due to high exposure to endotoxins. Allergen immunotherapy (AIT) is the only treatment of allergy modifying the immune response with the potential to change the natural history of allergic diseases. It seems that studies evaluating the efficacy of immunotherapy in large cohorts of allergic patients living in farm areas are needed to understand the influence of environment on immune response during AIT.

Aim. To compare the clinical effectiveness of immunotherapy between children living in farm versus urban areas.

Materials and methodsThis was a retrospective analysis of 87 children living in farm area (n=42) and city area (n=45), aged 8–16, who completed three years of subcutaneous immunotherapy due to allergic rhinitis/asthma. An AIT efficacy questionnaire has been designed to be filled in by the allergy specialist during a regular immunotherapy visit before and after AIT.

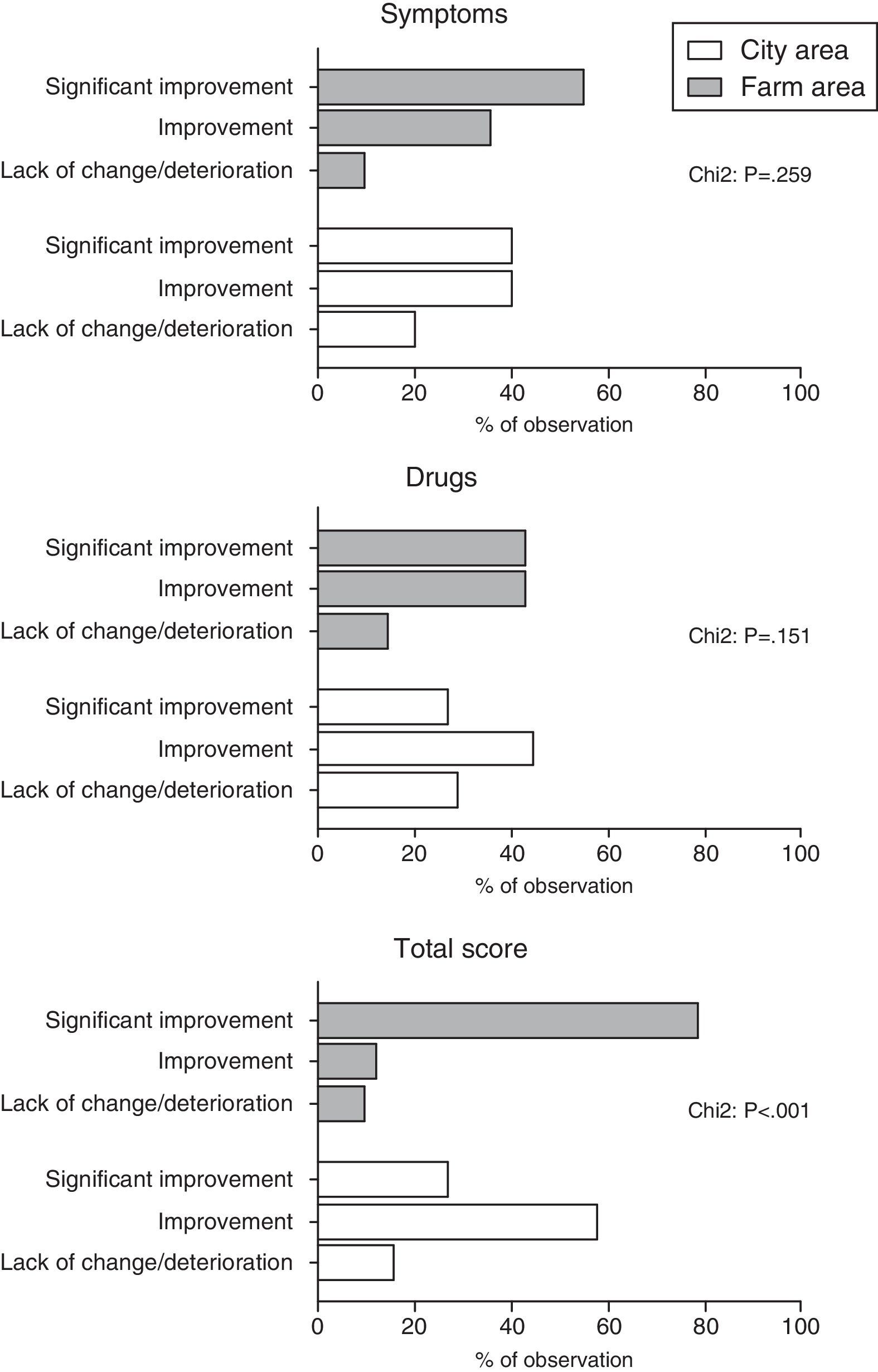

ResultsWe observed significantly higher improvement in total score among children from farm area compared to children from city area (p<0.001). Between-group differences in symptoms and drug scores did not reached the level of significance. Multivariate logistic regression analysis (adjustment for the effect of gender and type of allergy) showed that living in farm areas was independently associated with significant improvement in total score after immunotherapy (OR: 10.9; 95%CI: 3.7–32.2).

ConclusionThe current analysis of the better AIT effectiveness in the farm population has shown the protective influence of environmental exposures on asthma and allergic rhinitis in our children.

The protective effect of farming on asthma and atopy has been shown in numerous studies consistently across many parts of the world, and the beneficial effects of childhood farm exposure likely last until adulthood.1–3 It is considered that farm areas protect young patients from allergy and asthma due to high exposure to endotoxins. A recently-published study by Schuijs et al., showed that chronic exposure to endotoxin or farm dust protects mice from developing asthma.4 Allergen immunotherapy (AIT) is the only treatment of allergy modifying the immune response with the potential to change the natural history of allergic diseases in many atopic children. It seems that studies evaluating the efficacy of immunotherapy in large cohorts of allergic patients living in farm areas are needed in order to understand the influence of environment on immune response.

The aim of this pilot study is to compare the clinical effectiveness of immunotherapy between children living in farm versus urban areas.

Material and methodsThis was a retrospective analysis of 87 children living in farm area (n=42) and city area (n=45), aged 8–16, who completed three years of subcutaneous immunotherapy (dust mites, grasses, trees) in our allergy outpatient clinic due to allergic rhinitis and/or asthma, in years 2013–2015. Before immunotherapy there were no differences in asthma/allergic rhinitis severity between study groups. Children were considered as living in farm area if they lived on a farm run by their family and have everyday contact with farm animals or animal feed. All other children were considered as living in city area. Asthma/allergic rhinitis diagnosis was defined previously by the doctors according to GINA and ARIA guidelines.5,6

An AIT efficacy questionnaire7 has been designed to be filled in by the allergy specialist during a regular immunotherapy visit (based on the medical documentation) before and after AIT. The form includes evaluation of severity of symptoms related to asthma, rhinitis and conjunctivitis, as well as the intake and dosing of allergy and asthma medication. Each component was evaluated for a minimum score −2 (deterioration after AIT) and maximum score of +2 points (significant improvement after AIT). Total score reflected the average score for symptoms and drugs intake – a minimum score −2 (deterioration after AIT) and maximum score of +2 points (significant improvement after AIT).

The study was approved by the Ethical Committee of Medical University of LODZ, Lodz, Poland and a written consent was obtained from all the mothers before commencement of the study.

Statistical methodsDuring analysis of our data we used Chi square test to determine the difference between nominal variables. The associations between dependent, dichotomic variable and groups of independent variables (presented in Table 1) were analysed using logistic regression. First, logistic regression was used to assess the relationship between dependent variables and each one of the independent variables–univariate model. A stepwise forward procedure was then used to select variables. Predictors with p levels of at least 0.1 estimated in univariate models were included into multivariate regression analyses. All statistical analyses were performed using StatSoft Statistica for Windows, release 8.0 (StatSoft, Inc., Tulsa, USA). p<0.05 was used as the definition of statistical significance.

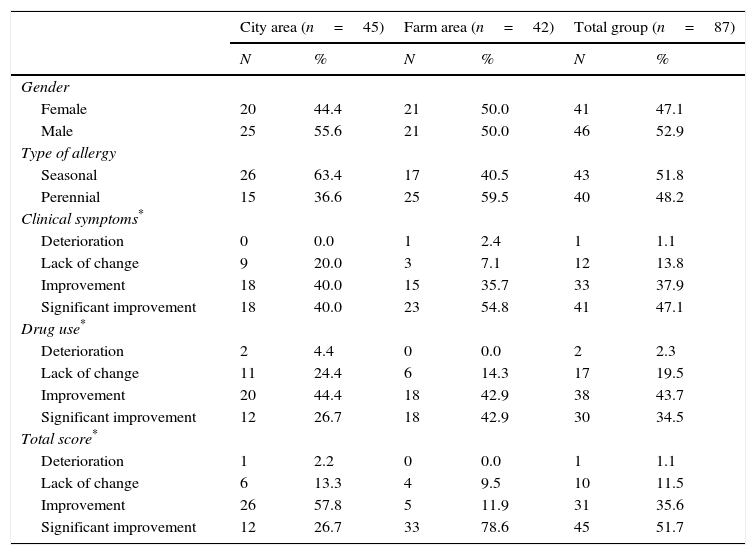

Clinical characteristics of study sample.

| City area (n=45) | Farm area (n=42) | Total group (n=87) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Gender | ||||||

| Female | 20 | 44.4 | 21 | 50.0 | 41 | 47.1 |

| Male | 25 | 55.6 | 21 | 50.0 | 46 | 52.9 |

| Type of allergy | ||||||

| Seasonal | 26 | 63.4 | 17 | 40.5 | 43 | 51.8 |

| Perennial | 15 | 36.6 | 25 | 59.5 | 40 | 48.2 |

| Clinical symptoms* | ||||||

| Deterioration | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 2.4 | 1 | 1.1 |

| Lack of change | 9 | 20.0 | 3 | 7.1 | 12 | 13.8 |

| Improvement | 18 | 40.0 | 15 | 35.7 | 33 | 37.9 |

| Significant improvement | 18 | 40.0 | 23 | 54.8 | 41 | 47.1 |

| Drug use* | ||||||

| Deterioration | 2 | 4.4 | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 2.3 |

| Lack of change | 11 | 24.4 | 6 | 14.3 | 17 | 19.5 |

| Improvement | 20 | 44.4 | 18 | 42.9 | 38 | 43.7 |

| Significant improvement | 12 | 26.7 | 18 | 42.9 | 30 | 34.5 |

| Total score* | ||||||

| Deterioration | 1 | 2.2 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 1.1 |

| Lack of change | 6 | 13.3 | 4 | 9.5 | 10 | 11.5 |

| Improvement | 26 | 57.8 | 5 | 11.9 | 31 | 35.6 |

| Significant improvement | 12 | 26.7 | 33 | 78.6 | 45 | 51.7 |

Eighty-seven children were included in the analysis. Clinical characteristics are given in Table 1.

We observed significantly higher improvement in total score among children from farm area compared to children from city area (p<0.001). Between-group differences in symptoms and drug scores did not reached the level of significance. (Fig. 1).

In the next step dichotomised all scores (according to the following formula: 1 – significant improvement and 0 – others) and included as dependent variables into three different models of logistic regression analysis. Multivariate logistic regression analysis (adjustment for the effect of gender and type of allergy) showed that living in farm areas was independently associated with significant improvement in total score after immunotherapy (OR: 10.9; 95%CI: 3.7–32.2). Changed in symptoms and drug scores were not associated with place of living of our patients.

DiscussionOur study is the first showing differences between efficacy of immunotherapy in children living in farm and city areas. After adjustment for the effect of gender and type of allergy we showed that living in farm area was independently associated with significant improvement in total score (symptoms+drugs use) after immunotherapy.

In the present study, treatment with AIT in all groups resulted in overall clinical improvement, however more children living in farm area responded better to AIT treatment based on the reduction in symptom-medication score (total score). The above phenomenon has not been described before in the literature. Keeping in mind a general rule that the effectiveness of immunotherapy depends on the modification of immune regulation, our findings are highly attractive especially in the light of the latest study by Schuijs et al. recently published.4 They showed that chronic exposure to low-dose endotoxin or farm dust protects mice from developing house dust mite-induced asthma. Endotoxin reduced epithelial cell cytokines that activate dendritic cells, thus suppressing type 2 immunity to house dust mites (HDMs).4 Their findings demonstrate that LPS protection blunts the innate immune response to HDMs, which they and others previously found to be driven by Toll-like receptor 4 on epithelial cells.8,9 Ege et al. identified 15 genes with strong interactions for asthma or atopy in relation to farming, contact with cows and straw, or consumption of raw farm milk.10 They concluded that common genetic polymorphisms are unlikely to moderate the protective influence of the farming environment on childhood asthma and atopy, but rarer variants, particularly of the glutamate receptor may do so. The explanation for our phenomenon may be found in potential interaction of immunotherapy and environmental farm exposures on the immunology system. However, this is a retrospective pilot study based on our observation, therefore we cannot be sure if farm children's symptoms improved from immunotherapy or it was because of living on a farm and exposure to endotoxin or both. The current analysis of the better AIT effectiveness in the farm population has shown the protective influence of environmental exposures on asthma and allergic rhinitis in our children. Given the retrospective design and limited statistical power of our study, these findings should be interpreted with caution before being replicated in prospective large cohort studies.

Financial informationThis study was funded by grant 503/2-056-01/503-01 from the Medical University of Lodz, Poland.

Conflict of interestThere is no conflict of interest.

Ethical disclosuresConfidentiality of dataThe authors declare that no patient data appears in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appears in this article.

Protection of human subjects and animals in researchThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this investigation.