Pollen-food syndrome (PFS) is an allergic reaction to fresh fruits, vegetables and/or nuts that can occur in patients who are allergic to pollen. The prevalence of PFS in children is not clearly known.

ObjectiveThe objective of this study was to determine the frequency and clinical features of PFS in pediatric patients with pollen-induced allergic rhinitis (AR).

MethodThis study was conducted in the pediatric allergy outpatient clinic of our hospital. Pollen-induced seasonal AR patients who were evaluated for any symptoms appearing after consuming any fresh fruits and vegetables.

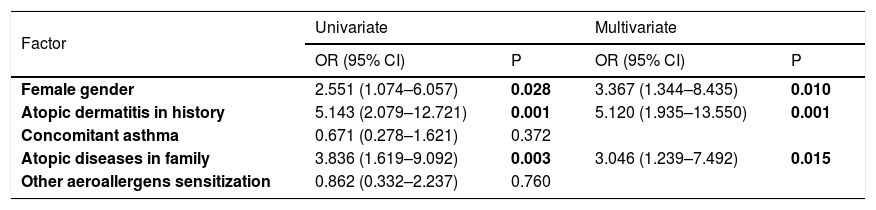

ResultsSix hundred and seventy-two pollen-sensitized patients were included in this study. The symptoms related to PFS were reported in 22 (3.3%) patients. The median age of the patients was 12.3 years and 59% (n=13) were female. Peach was the most common culprit (22%). There were isolated oropharyngeal symptoms in 20 (91%) patients and anaphylaxis in two (9%) patients with the suspected food. The multiple logistic regression analysis revealed that female gender, history of atopic dermatitis and allergic diseases in the family were the potential risk factors for PFS [Odds ratio 95%CI: 3.367 (1.344–8.435), 5.120 (1.935–13.550), 3.046 (1.239–7.492), respectively].

ConclusionPFS can be seen in children who are followed up for pollen-induced AR. The symptoms of PFS are usually mild and transient. However, comprehensive evaluation of patients is important since serious systemic reactions such as anaphylaxis can also be observed.

Pollen-food syndrome (PFS) also known as oral allergy syndrome (OAS) is an allergic reaction to fresh fruits, vegetables and/or nuts that can occur in patients who are allergic to pollen.1–4 These reactions are mediated by immunoglobulin E antibodies to food, caused by cross-reactivity between pollen allergens and allergens of food of plant origin. Isolated oropharyngeal symptoms such as lip/mouth itching and swelling are reported by most patients with PFS.3–5 These symptoms resolve promptly when the food is swallowed due to destruction of the structure of the allergen by gastric acid and proteolytic digestive enzymes.6 However, reactions that progress beyond the mouth and anaphylaxis can also occur in 7% and 1–2% of the patients, respectively.7

The prevalence of PFS is difficult to estimate because data are based upon selected pollen allergic patients and not the general population. In adults with allergic rhinitis (AR), the prevalence of PFS has been shown to vary between 14.4% and 70%.8–10 PFS has rarely been explored in the pediatric population, since it is considered primarily an adult problem.

Although a few studies have shown that the prevalence of PFS in children ranges from 5% to 93%,11–18 the prevalence of PFS in children is not clearly known.

The aim of this study was to determine the frequency and clinical features of pollen food syndrome in pediatric patients with AR and the possible risk factors for its development. For this purpose, we included children with AR who admitted to our outpatient clinic.

Materials and methodsThis study was conducted in the pediatric allergy outpatient clinic of our hospital. Pollen-sensitized patients who were being followed up with a diagnosis of AR and/or asthma were evaluated for any symptoms appearing after consuming any fresh fruits and vegetables.

Inclusion criteria for the study: i) ≤18 years; ii) a history of pollen-induced AR in previous pollen seasons; iii) proven positive skin-prick tests (SPTs) for the pollen extracts.

Exclusion criteria for study: i) previous immunotherapy for any pollen allergen; ii) any other severe chronic disease.

Patients were classified as having PFS if they reported clear allergic symptoms compatible with PFS (pruritus, paresthesia and angioedema of the oral mucosa, tongue, lips, palate and oropharynx, or generalized symptoms, such as urticaria, rhinitis, conjunctivitis, asthma attack, anaphylaxis) immediately after the consumption of typical pollen-associated foods. Additionally, demographic data, history of atopic disease, clinical features of the concomitant allergic disease(s), and relevant medical history were recorded.

All the patients and parents provided written informed consent for the study procedures, and the institutional review board of our hospital approved the study.

Skin test proceduresAll patients underwent SPTs with commercial aeroallergen extracts (Stallergenes, SA, Antony, France) as follows:

Pollens:Grass pollens: Mixture of 12 grass pollen (Dactylis glomerata, Lolium perenne, Phleum pratense, Poa pratensis, Anthoxantum odoratum, Avena sativa, Avena sterilis, Festuca eliator, Agrostis vulgaris, Holcus lanatus, Cynodon dactylon, Bromus inermis), Tree pollens: Mixture of tree pollens (Alnus glutinosa, Betula verrucosa, Corylus avellana), Saliceae, Oleceae europaea], Weed pollens: Mixture of three cereal pollens (Avena sativa, Triticum vulgare, Hordeum vulgare, Zea mays), Betula alba, Artemisia vulgaris, Compositae, Pariteria officinalis.

House-dust mites: Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus and Dermatophagoides farinae

Mold: Aspergillus mix (Aspergillus fumigatus, Aspergillus nidulans, Aspergillus niger), Alternaria alternata, Cladosporium mix (Cladosporium cladosporioides, Cladosporium herbarum)]

Animal dander and epithelium: Cat and dog

Cockroach (Blatella germanica)

Suspected pollen-associated foods: Fruits (apple, apricot, cherry, banana, cucumber, kiwifruit, melon, orange, peach, pineapple, plum, pomegranate, strawberry, watermelon, tomato), vegetables (potato)

All patients who reported symptoms of PFS underwent prick-by-prick test with the suspected fresh foods.

Histamine (10mg/mL) was used as a positive control and diluent as a negative control for the test. Skin prick tests were performed on the volar forearm, and were read after 20min. SPT results were considered positive if a wheal size was ≥3mm compared with the negative control.

Statistical analysisThe statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS program version 23.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, New York, USA). We expressed categorical variables as percentages. The distribution of quantitative data was determined according to Shapiro–Wilk test and visual inspection of histograms and normal Q–Q plots. The values are presented as means and standard deviations (SD) for data that demonstrated a normal distribution and as medians and interquartile ranges for data that did not demonstrate a normal distribution. Chi-square test was performed to compare the categorical variables, Mann–Whitney test was used to compare the non-normally distributed continuous variables, and the independent t-test was used for normally distributed continuous data to compare patients with anaphylaxis and isolated oropharyngeal symptoms. Univariate and multivariate regression analyses were performed to determine risk factors for PFS. Variables that were associated with the outcomes in the univariate analysis, at a p value of <0.25, were entered into multivariate logistic regression models using the stepwise selection technique. The results of the logistic regression analysis were expressed as odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs). A p value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

ResultsSix hundred and seventy two pollen-sensitized patients were included in this study. The median (Interquartile range-IQR) age of the patients was 11.92 (8.58–15.25) years and 63.1% (n=424) were male. The vast majority of the patients were sensitized to grass pollens (96%, n=645). Two hundred and three patients (30.2%) had another aeroallergen sensitization in addition to pollen sensitization and 45.7% (n=307) of children had concomitant asthma.

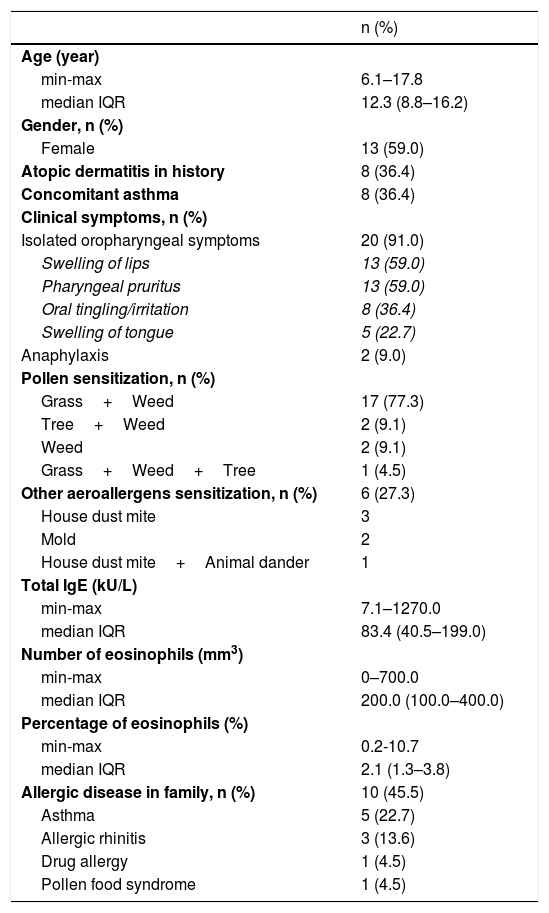

Of the patients, 3.3% (n=22) reported symptoms related to PFS. There were isolated oropharyngeal symptoms in 20 (91%) patients and anaphylaxis in two (9%) patients with the suspected food. The median (IQR) age of the patients with a history of PFS was 12.3 (8.8–16.2) years and 59% (n=13) of them were female. The majority of the patients were sensitized to grass plus weed pollens (77.3%, n=17) and 36.4% (n=8) of children had concomitant asthma. Characteristics of the patients are shown in Table 1.

Characteristics of patients with pollen food syndrome (n=22).

| n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Age (year) | |

| min-max | 6.1–17.8 |

| median IQR | 12.3 (8.8–16.2) |

| Gender, n (%) | |

| Female | 13 (59.0) |

| Atopic dermatitis in history | 8 (36.4) |

| Concomitant asthma | 8 (36.4) |

| Clinical symptoms, n (%) | |

| Isolated oropharyngeal symptoms | 20 (91.0) |

| Swelling of lips | 13 (59.0) |

| Pharyngeal pruritus | 13 (59.0) |

| Oral tingling/irritation | 8 (36.4) |

| Swelling of tongue | 5 (22.7) |

| Anaphylaxis | 2 (9.0) |

| Pollen sensitization, n (%) | |

| Grass+Weed | 17 (77.3) |

| Tree+Weed | 2 (9.1) |

| Weed | 2 (9.1) |

| Grass+Weed+Tree | 1 (4.5) |

| Other aeroallergens sensitization, n (%) | 6 (27.3) |

| House dust mite | 3 |

| Mold | 2 |

| House dust mite+Animal dander | 1 |

| Total IgE (kU/L) | |

| min-max | 7.1–1270.0 |

| median IQR | 83.4 (40.5–199.0) |

| Number of eosinophils (mm3) | |

| min-max | 0–700.0 |

| median IQR | 200.0 (100.0–400.0) |

| Percentage of eosinophils (%) | |

| min-max | 0.2-10.7 |

| median IQR | 2.1 (1.3–3.8) |

| Allergic disease in family, n (%) | 10 (45.5) |

| Asthma | 5 (22.7) |

| Allergic rhinitis | 3 (13.6) |

| Drug allergy | 1 (4.5) |

| Pollen food syndrome | 1 (4.5) |

Min–max: minimum-maximum; IQR: Interquartile range.

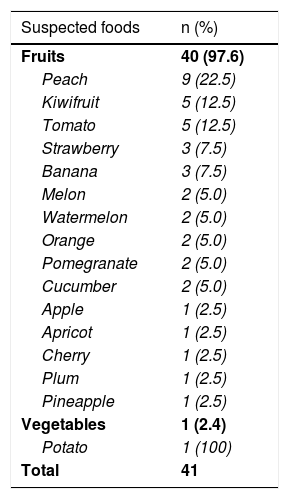

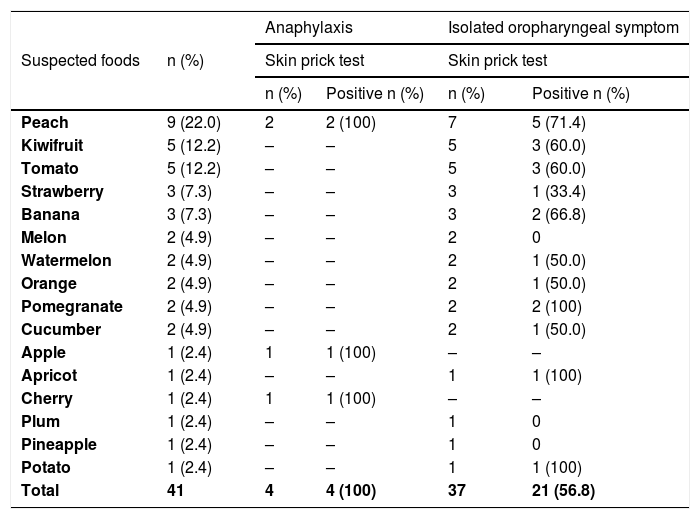

In 22 patients, there was a history of reactions with 41 foods; 97.6% (n=40) of the suspicious foods were fruits (Table 2). Peach was the most common fruit trigger (22.5%, 9/40). The skin prick tests were performed with fresh foods for all of the patients with PFS associated symptoms. The results of skin prick tests with suspected foods are presented in Table 3. Of the 41 skin prick tests with suspicious foods, 61% (n=25) were positive. Skin prick tests with suspected foods were positive in 56.8% (n=21) of patients with isolated oropharyngeal symptom and 100% (n=4) of patients with anaphylaxis (Table 3). PFS with at least one food was confirmed in all patients with anaphylaxis (n=2/2) and 85% (n=17/20) of patients with isolated oropharyngeal symptoms. Diagnosis of PFS with at least one food was confirmed in 19 (86.4%) of 22 patients (eTable1).

Suspected foods.

| Suspected foods | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Fruits | 40 (97.6) |

| Peach | 9 (22.5) |

| Kiwifruit | 5 (12.5) |

| Tomato | 5 (12.5) |

| Strawberry | 3 (7.5) |

| Banana | 3 (7.5) |

| Melon | 2 (5.0) |

| Watermelon | 2 (5.0) |

| Orange | 2 (5.0) |

| Pomegranate | 2 (5.0) |

| Cucumber | 2 (5.0) |

| Apple | 1 (2.5) |

| Apricot | 1 (2.5) |

| Cherry | 1 (2.5) |

| Plum | 1 (2.5) |

| Pineapple | 1 (2.5) |

| Vegetables | 1 (2.4) |

| Potato | 1 (100) |

| Total | 41 |

Skin prick test result with suspected foods (n=41).

| Suspected foods | n (%) | Anaphylaxis | Isolated oropharyngeal symptom | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Skin prick test | Skin prick test | ||||

| n (%) | Positive n (%) | n (%) | Positive n (%) | ||

| Peach | 9 (22.0) | 2 | 2 (100) | 7 | 5 (71.4) |

| Kiwifruit | 5 (12.2) | – | – | 5 | 3 (60.0) |

| Tomato | 5 (12.2) | – | – | 5 | 3 (60.0) |

| Strawberry | 3 (7.3) | – | – | 3 | 1 (33.4) |

| Banana | 3 (7.3) | – | – | 3 | 2 (66.8) |

| Melon | 2 (4.9) | – | – | 2 | 0 |

| Watermelon | 2 (4.9) | – | – | 2 | 1 (50.0) |

| Orange | 2 (4.9) | – | – | 2 | 1 (50.0) |

| Pomegranate | 2 (4.9) | – | – | 2 | 2 (100) |

| Cucumber | 2 (4.9) | – | – | 2 | 1 (50.0) |

| Apple | 1 (2.4) | 1 | 1 (100) | – | – |

| Apricot | 1 (2.4) | – | – | 1 | 1 (100) |

| Cherry | 1 (2.4) | 1 | 1 (100) | – | – |

| Plum | 1 (2.4) | – | – | 1 | 0 |

| Pineapple | 1 (2.4) | – | – | 1 | 0 |

| Potato | 1 (2.4) | – | – | 1 | 1 (100) |

| Total | 41 | 4 | 4 (100) | 37 | 21 (56.8) |

Oral provocation test with suspicious foods was planned. However, we could not obtain informed consent from the patients and/or their families.

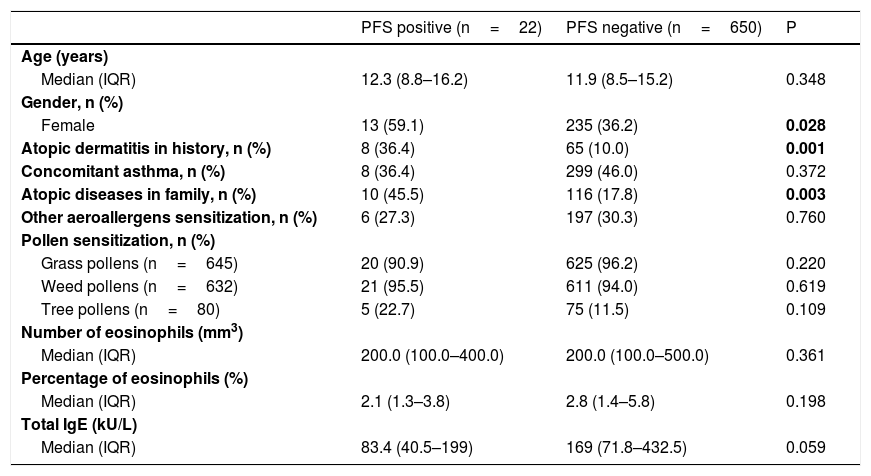

Comparison of patients with and without pollen food syndromeThere was no difference in terms of age, concomitant asthma, asthma control status, other aeroallergen sensitization and species of pollen with sensitization between patients with and without PFS. However, patients with PFS were mostly female (p=0,028). There was more history of atopic dermatitis, and allergic diseases in the family were more frequent among patients with PFS (respectively p=0.001, 0.003) (Table 4). When the multivariate regression analysis was performed, it was observed that the main risk factors for PFS were female gender, history of atopic dermatitis, and allergic diseases in the family [3.367 (1.344–8.435), 5.120 (1.935–13.550), 3.046 (1.239–7.492), respectively] (Table 5).

Comparison of patients with and without pollen food syndrome.

| PFS positive (n=22) | PFS negative (n=650) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | |||

| Median (IQR) | 12.3 (8.8–16.2) | 11.9 (8.5–15.2) | 0.348 |

| Gender, n (%) | |||

| Female | 13 (59.1) | 235 (36.2) | 0.028 |

| Atopic dermatitis in history, n (%) | 8 (36.4) | 65 (10.0) | 0.001 |

| Concomitant asthma, n (%) | 8 (36.4) | 299 (46.0) | 0.372 |

| Atopic diseases in family, n (%) | 10 (45.5) | 116 (17.8) | 0.003 |

| Other aeroallergens sensitization, n (%) | 6 (27.3) | 197 (30.3) | 0.760 |

| Pollen sensitization, n (%) | |||

| Grass pollens (n=645) | 20 (90.9) | 625 (96.2) | 0.220 |

| Weed pollens (n=632) | 21 (95.5) | 611 (94.0) | 0.619 |

| Tree pollens (n=80) | 5 (22.7) | 75 (11.5) | 0.109 |

| Number of eosinophils (mm3) | |||

| Median (IQR) | 200.0 (100.0–400.0) | 200.0 (100.0–500.0) | 0.361 |

| Percentage of eosinophils (%) | |||

| Median (IQR) | 2.1 (1.3–3.8) | 2.8 (1.4–5.8) | 0.198 |

| Total IgE (kU/L) | |||

| Median (IQR) | 83.4 (40.5–199) | 169 (71.8–432.5) | 0.059 |

IQR: Interquartile range.

Risk factors for pollen-food syndrome by logistic regression analysis.

| Factor | Univariate | Multivariate | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P | OR (95% CI) | P | |

| Female gender | 2.551 (1.074–6.057) | 0.028 | 3.367 (1.344–8.435) | 0.010 |

| Atopic dermatitis in history | 5.143 (2.079–12.721) | 0.001 | 5.120 (1.935–13.550) | 0.001 |

| Concomitant asthma | 0.671 (0.278–1.621) | 0.372 | ||

| Atopic diseases in family | 3.836 (1.619–9.092) | 0.003 | 3.046 (1.239–7.492) | 0.015 |

| Other aeroallergens sensitization | 0.862 (0.332–2.237) | 0.760 | ||

OR: Odds ratio; CI: Confidence interval.

In our study, 672 children with pollen-induced seasonal AR were evaluated and the incidence of PFS was found at 3.3%. 91% of patients with PFS had isolated oropharyngeal symptoms and 9% had anaphylaxis. The most common cause of PFS was peach.

The most common form of food allergies in adults is PFS.1–4 Therefore, the studies on PFS have been mostly conducted in adult patients and the incidence of PFS has been reported between 14.4–70%.8–10 However, there is no definitive epidemiological data on the prevalence of PFS in children due to the lack of controlled, extensive and population-based studies involving oral provocation tests. In parallel with the increase in the incidence of AR in recent years, the incidence of PFS is also expected to increase. In a small number of studies conducted in children, the incidence of PFS varies between 5% and 48%.11–17 However, in a study of 72 children with pollen-induced severe allergic rhinoconjunctivitis and who had undergone immunotherapy, the PFS rate was reported at a very high rate of 93%.18 It can be concluded that the incidence of PFS changes according to the patient group and the geographical region selected in children as well as in adults.

Furthermore, due to regional differences in pollen distribution, it has been shown that the incidence of PFS and related foods in adults varied between geographic regions.3 While the most common food that causes PFS in adults has been apple in Central and Northern European countries, it has been mostly associated with peaches and cherries in southern European countries such as Spain, Italy and Portugal.4 In our country, which is in the transition point between Asia and Europe, kiwifruit was found to be the most commonly associated food with PFS in adult patients. In studies conducted in children the most common foods that cause PFS in children are pineapple, kiwifruit, apple, watermelon and tree nuts.11–18 In our study, the most common food triggers were peach.

In adult studies, some risk factors associated with PFS have been identified. However, there is no consensus on risk factors. In Caliskaner et al.,8 female gender, older age and presence of asthma, and in the study conducted by Kepil Ozdemir et al.,9 family history of asthma and atopic dermatitis were shown as risk factors for PFS. Although these two studies were conducted in the same country (Turkey), different risk factors were identified. However, several studies conducted among adults in the literature have also shown that there was no association between age, sex, and asthma and PFS.10 In previous pediatric studies, older age,14,16,17 female gender,14,16 concomitant asthma and atopic dermatitis,15,16 environmental cigarette exposure,16 the length of the AR duration,16 having a mother with PFS,16 presence of atopic disease in the family16 were reported as risk factors for PFS. In our study, we found that female gender, presence of a history of atopic dermatitis, and presence of allergic disease in the family were more frequent in patients with PFS. However, it is not fully elucidated why and how these risk factors in all these studies have increased the incidence of PFS. Future studies are needed to clarify the relationship between these risk factors and PFS, and existing studies will guide for this issue.

Skin prick test with the suspected fresh foods is recommended for the diagnosis of PFS. In our study, skin tests were performed on all of the patients as diagnostic tests. In total, 61% of patients had positive skin tests. Furthermore, we found 100% positive rates with pomegranate, apple, apricot and cherry. There is not much data in the literature about skin tests with fresh foods in children with PFS. In the study conducted by Ludman et al., the skin prick tests showed high sensitivity for peach, cherry, carrot, and strawberry, and the negative predictive value was found to be 100%. SPT sensitivity was found to be close to 50% for tomato, watermelon, nuts, and peanuts.17

Although pollen food syndrome usually presents with symptoms restricted to oral mucosa, it is now well known that systemic symptoms can also be present. In our study, two (9%) of patients with PFS had anaphylaxis with suspected foods. As far as we could find, there have been only two studies conducted in children to give a frequency of anaphylaxis. Mastrorilli et al.16 reported a frequency of anaphylaxis of 10% of children with PFS and a frequency of 2.3% among patients with pollen allergy. Dondi et al.14 presented a frequency of 5.6% of anaphylaxis among children with pollen allergy but did not specify the frequency among children with PFS.

There were some limitations in our study. Firstly, oral provocation test with suspicious foods could not be done because we could not obtain informed consent from the patients and/or their families. However, all of the patients had a strong and recurrent clinical history. On the other hand, false negative results could also be seen in oral provocation tests due to lack of standard protocols, variability of nutrients and pollen exposure status. Another limitation of our study was the inability to perform molecular diagnostic tests (component resolved diagnosis-CRD). The studies have shown that PFS symptoms are caused by proteins called panallergens. Among these, the most typical are the profilins and the PR (pathogenesis related protein)-10 group, which are sensitive to heat and proteases.4,5 Symptoms associated with these molecules remain limited to the oropharyngeal region. Other molecules that cause cross-reactivity such as LTP (Lipid transfer protein) or PR-14 are not affected by heat and proteases since they are more stable and may lead to a systemic reaction.19,20 Molecular studies may show that these proteins can be etiologically diagnosed by showing the presence of sIgE in the individual. However, the studies have also shown that the clinical history and CRD outcomes did not always coincide.21

In conclusion, PFS can be seen in children who are followed up for pollen-induced AR. Since symptoms of PFS are usually mild and transient, patients are able to tolerate symptoms, prefer not to consume the cause of the complaint, and do not complain if not particularly questioned. Therefore, the frequency of actual PFS in children may be higher. However, as seen in our study, comprehensive evaluation of patients with allergy tests is also important for children, since serious systemic reactions such as anaphylaxis can also be observed. Patients with isolated oropharyngeal symptoms to raw foods that are not high-risk for systemic reactions need only avoid the raw foods that cause symptoms. There is no reason to restrict cooked or processed forms of the food that do not cause symptoms. However, patients with systemic symptoms should definitely avoid from risky foods for PFS.

Conflicts of interestNone.

Funding sourceNone.