Hepatitis A is a usually benign and self-limited disease in paediatric age, however, 15% of the cases can have some kind of complication. Mortality is low (less than 1/1000), and hepatitis A virus infection can be subclinical, anicteric or icteric. This variability is correlated to age, and the forms are milder in children under 6 years in which only 10% are icteric. These figures reach up to 70–80% in children above 14 years.

Atypical (very rare) presentations have classically been described, especially in adults, such as cholestatic, recurring or fulminant hepatitis A and in the last few years it has been associated to different extra-hepatic complications or manifestations such as pleural effusion, thrombopenia, etc., which are more frequent when associated to another type of viral hepatitis and in adults.

The case of a 6-year-old patient with hepatitis A is presented with associated pleural effusion, thrombopenia, leucopoenia, hypoproteinaemia, coagulopathy and exanthema with spontaneous evolution to curing, which is commonly described in the literature.

A 6-year-old school child consulting for fever of up to 39°C, abdominal pain, asthenia and anorexia with an evolution of 6 days. Forty-eight hours after the onset of the symptoms, he presented generalised pruriginous urticarial exanthema with petechial elements prevailing in the lower limbs. He was diagnosed with gastroenteritis and allergic reaction and was treated with diet and dexchlorpheniramine. He was sent to this hospital for thrombopenia. It should be emphasised for the record that he was not born in Spain, although he has lived here since he was a month old. He visited his birthplace 10 months ago. There is no other family or personal history of interest.

His physical examination on admission was: weight 18kg. Good general condition. Palpable peripheral pulses and normal revascularisation time. Acceptable nutrition and hydration. Cardiopulmonary auscultation: rhythmic, without murmurs, good bilateral ventilation, without pathological noises. Abdomen soft and depressible, hepatomegaly at 4–5cm under costal margin. Normal pharynx. Normal otoscopy. At skin level, he presented macular exanthema in cheeks and pruriginous trunk. In lower limbs, he presented non-painful purpuric elements with a diameter of approximately 1cm, especially on the back of the feet and pretibials. Normal neurological examination.

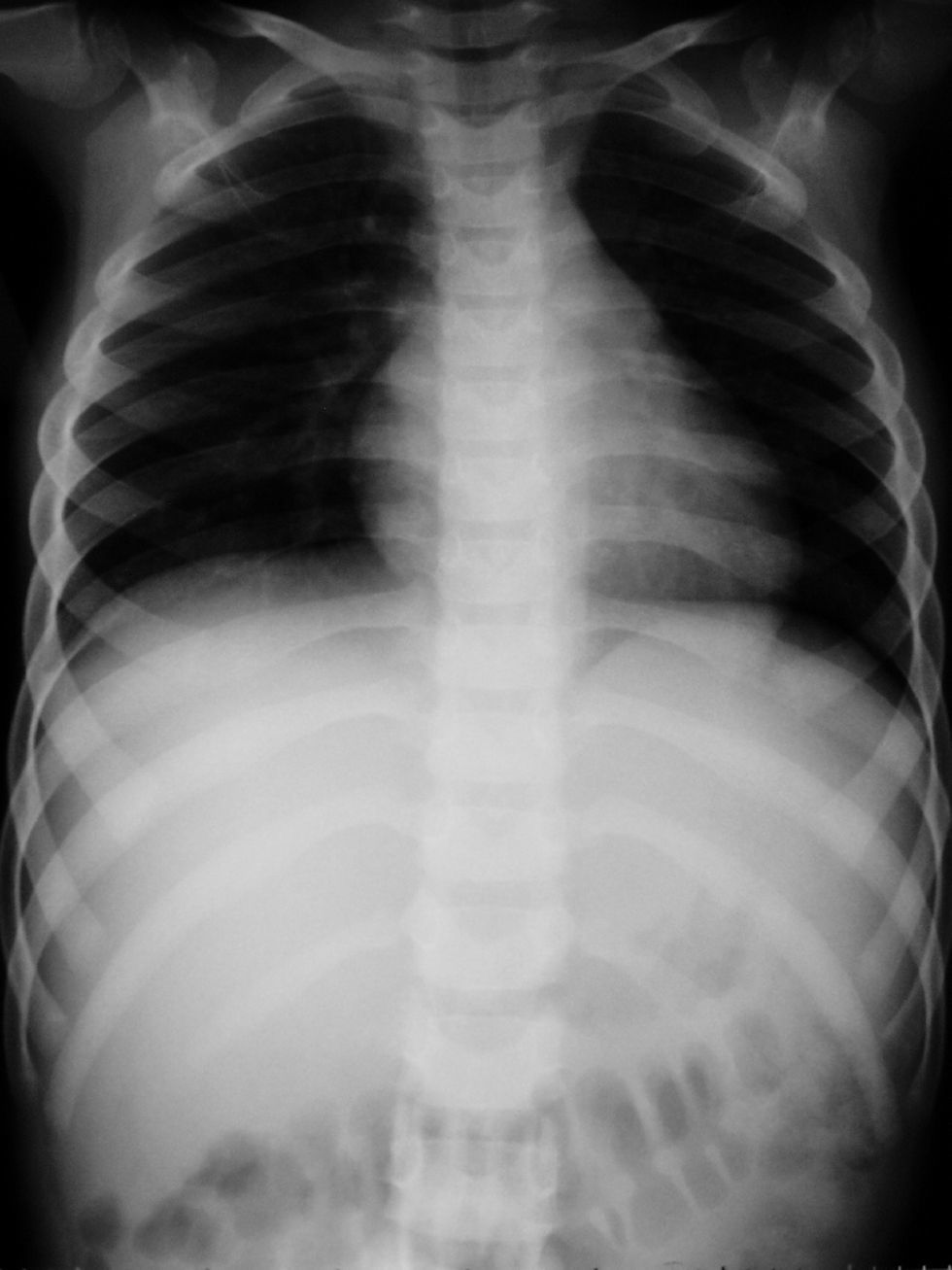

Supplementary test were done to the child to admission: Haemogram: haemoglobin 11.4g/dl, hematocrit 34%, leukocytes 2860/microL, (picture: N 54%, L 31.1%, M 9.8%). Platelets 25,000/microL; Biochemistry: Normal ions. Normal creatinine and urea. Total proteins 5.4g/dl, albumin 2.3g/dl. C-reactive protein 17mg/dl. Total bilirubin 3mg/dl, GOT/GPT 212/83, alkaline phosphatase 67U/L and GGT 24U/L; Normal coagulation; Normal chest X-ray upon admission (Figure 1).

He was admitted with fluidotherapy. Antipyretic-analgesic drugs and antibiotics (cefotaxime 11 days) were prescribed due to the rise of C-reactive protein. He was also subjected to isolation enteric. Serial analytical controls were performed with the slow recovery of the platelet figures. Abdominal ultrasound scan (8th day of admission): hepatomegaly without evidence of focal lesions and non-partitioned right pleural effusion; the rest is normal.

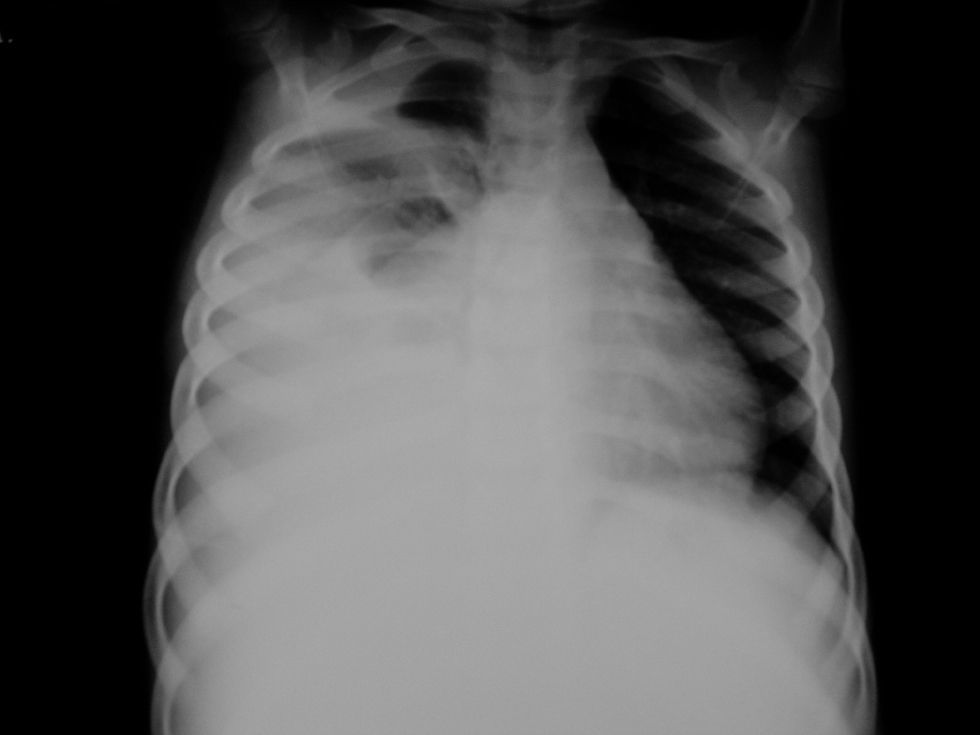

He suffered a progressive clinical worsening (until the tenth day of admission), with the onset of generalised jaundice, hypoventilation in right pulmonary field, without presenting respiratory difficulty, with a rise of liver enzyme figures of up to GOT/GPT 387/697 and alkaline phosphatase 312, total bilirubin 4.9, with direct bilirubin 3.35 and GGT 273 and coagulation disorder (prothrombin activity 39%). There was evidence of progression of the pleural effusion until the opacification of the right pulmonary field (Figure 2), continuing without any important clinical repercussion (thoracentesis was not authorised) with venous blood-gas (10th day of admission): normal.

During admission serology was done: Brucella, Salmonella, Rickettsia Chlamydia negative. Cytomegalovirus IgG positive. Hepatitis B and C virus, HIV, toxoplasma, varicella-zoster and parvovirus negative. Rubeola, cytomegalovirus and herpes simplex 1 and 2 virus IgG positive. Hepatitis A virus IgM positive; Supplement: C3 47mg/dl and C4 0.72mg/dl; Autoimmunity: antiphospholipid and anticardiolipin antibodies positives: 1/320; Normal ammonium. Normal renal function study. Abnormal and normal urine sediment. Urine culture, haemoculture and pharyngeal smear culture negative. Mantoux negative. Normal cardiological study (cardiopulmonary auscultation, electrocardiogram and Doppler echocardiography).

Around the 12th day of admission he presented a progressive improvement, and had no fever, with a fast reduction of the pleural effusion, disappearance of fever and improvement of hepatopathy and jaundice. When he was discharged, the liver enzymes had decreased, coagulation and the chest X-ray were normal and he was asymptomatic.

Our diagnosis was: Hepatitis A, Pleural Effusion, Thrombopenia, Hypoproteinaemia and Coagulopathy.

In subsequent controls, the normalisation of all the clinical and analytical parameters was observed. In the last check-up, the autoimmunity studies showed normal results.

Pleural effusion has been described as a rare extra-hepatic complication of acute viral hepatitis1–5, but it is considered to be a rarer complication in the case of hepatitis A1. There are very few published cases, especially in children, and nine cases have been found in the literature search conducted. In most of the reviewed cases, it does not cause any important clinical features and is usually spontaneously resolved1,3, despite the fact that the actual hepatitis causes mortal liver failure2. As the main characteristics: its onset is usually in the pre-icteric stage or at the end of the icteric stage1,2 (as in the case presented), it usually relates to transudates (especially in relation to hepatitis A), in which anti-VHA2 IgM has been detected; it is occasionally also associated to ascites, even pericarditis4 (not in this case) and frequently located in the right hemithorax1. The mechanism through which it occurs is unknown but it does not seem to be correlated to clinical evolution or to a worse prognosis of the disease; some authors defend autoimmune etiology (mediated by immunocomplexes)3, other authors defend parainflammatory etiology (as a result of liver inflammation).

Association between infectious disease (viral, bacterial or parasitic) and presence of autoantibodies in individuals who do not have autoimmune disease, but genetically predisposed, has been described6. HAV infection with lupus-like syndrome has also been associated with arthralgia, exudative pleural effusion and cells and antibodies of lupus erythematosus (antinuclear antibodies, anti-ds-DNA and anticardiolipin antibodies) also associated with impaired liver function with liver biopsy and diagnosis of acute hepatitis with submassive hepatic necrosis with hepatic function recovery and disappearance of antibodies after a short course of steroids. It has also been observed after measles and Ebstein-Barr virus infection7. Others articles discuss the frequency which antiphospholipid antibodies are found, mainly anticardiolipin, associated with viral infections8 (as in our case) and the presence of anti-cytoplasmic antibodies associated with HAV infection9. In all cases, these autoimmune features disappeared after treatment with steroids6,7.

Thrombopenia has been described in relation to some types of hepatitis, especially hepatitis B and C, however it is uncommon in hepatitis A; its evolution is benign and self-limited5. A peripheral platelet destruction is proposed to explain it, since normal megakaryocytes have been found in bone marrow4; this destruction can be explained by an autoimmune mechanism (by circulating immunocomplexes, antiplatelet antibodies or by the development of antiphospholipid or transient anticardiolipin antibodies)5. Six cases of thrombocytopenic purpura associated to hepatitis A have been described in children and adolescents up to 2005. Some of them needed transfusions4 or treatment with intravenous immunoglobulin5, with a favourable evolution of the disease in all of them.

Several types of exanthemas have been described as prodromes in hepatitis, predominantly in adults and associated to hepatitis B. In this case, it was labelled as an allergic reaction, although he presented characteristics of vasculitis upon admission.

In conclusion, it is very likely that in developed countries the clinical pattern of hepatitis A undergoes important changes, because when the age of presentation increases due to the improvement of the healthcare conditions, the risk of suffering from complications increases.

In this case, it is believed that the complications are due to autoimmune mechanisms, because of the rise of the antiphospholipid and anticardiolipin antibodies in the acute stage.

Hepatitis A is usually a benign and self-limited disease, but special attention must be paid to its complications when they occur.