This study examined the relationship between different food groups and the adherence to a Mediterranean diet during pregnancy and the risk of wheezing and eczema in children aged 12–15 months.

MethodsThe study involves 1087 Spanish infants from the International Study of Wheezing in Infants (Estudio Internacional de Sibilancias en Lactantes, EISL). The study of the association of the different food consumption and Mediterranean diet with wheezing, recurrent wheezing and eczema was performed using different models of unconditional logistic regression to obtain adjusted prevalence odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI).

ResultsNo association was found between a good adherence to the Mediterranean diet during pregnancy and the development of wheezing (p=0.372), recurrent wheezing (p=0.118) and eczema (p=0.315). The consumption once or twice a week of white fish (OR: 1.95[1.01–3.75]), cooked potatoes (OR: 1.75[1.22–2.51]) and industrial pastry (OR: 1.59[1.13–2.24]), and the consumption more than three times a week of industrial pastry (OR: 1.47 [1.01–2.13]) during pregnancy increases the risk of “wheezing” at 12 months. Instead, high fruit consumption during the pregnancy has a protective effect against “wheezing” in 12-month-old infants (OR: 0.44 [0.20–0.99]). No statistically significant differences were observed between food intake during pregnancy and “recurrent wheezing”. No statistically significant differences were observed between the consumption of any food during pregnancy and the presence of eczema at 12 months.

ConclusionsThe present study showed that the consumption of Mediterranean diet during pregnancy did not have a protective effect for wheezing, recurrent wheezing or eczema.

Wheezing and atopic dermatitis are two frequent disorders in the first years of life. Wheezing is one of the most frequent causes of primary care and emergency attendance in toddlers.1 Atopic dermatitis is common in the first two years of life with a decrease in prevalence afterwards.2 Both diseases have a great impact in the life of the child and its family.

It has been suggested that maternal diet during pregnancy may impact foetal immune development and subsequently alter the allergic responses in the child.3,4 The identification of which dietary pattern or nutrients during pregnancy affect the incidence of wheezing and eczema in toddlers is relevant to primary prevention of these common diseases.

There are few studies that evaluate the dietary patterns in the pregnant population in association with wheezing and eczema in early childhood with inconsistent or non-statistically evidence.4–6 The Greek-Spanish study concluded that Mediterranean diet adherence was not associated with the risk of wheezing and eczema.5 In a recent Spanish study, a significant association was not observed between Mediterranean diet and a protective effect on wheezing or eczema, while maternal consumption during pregnancy of meat one or two times/week and pasta never or occasionally remained as protective factors of wheezing.4 In a previous study, there was no relationship between the adherence to Mediterranean diet during pregnancy and wheezing in the first year of life, however they found a protective effect of olive oil use during pregnancy on wheezing during the first year of the offspring's life.6

In the current study we examined the relationship between different food groups and the adherence to a Mediterranean diet during pregnancy and the risk of wheezing and eczema in children aged 12–15 months.

Materials and methodsThis study was part of the International Study of Wheezing in Infants (EISL), a multicentre, cross-sectional, international study conducted in countries of Europe and Latin America. A standardised, validated written questionnaire was used in all participating centres.7 The EISL questionnaire is based on that of the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC).8

The questionnaires were filled out by parents in 20 primary care centres in the region of Pamplona, in the health check-up at 12–15 months of age. Paediatric nurses of the primary health centres explained the study to parents or guardians.

The questionnaire includes questions on wheezing in the first year of life and possible associated risk and protective factors. It also includes demographic data such as age, sex, race, weight and length at birth, current weight and height, premature birth, duration of exclusive breastfeeding, the presence or absence of asthma, rhinitis or eczema in parents, age and education of the mother.

For the purposes of this study, “wheezing” was defined as a positive answer to the question “Has your child wheeze in the first 12 months of his/her life”. “Recurrent wheezing” was defined as three or more episodes of wheezing in the first year of life.8

The child was considered to have eczema when parents or guardians answered affirmatively to the following question: “Has your child had an itchy rash (eczema) which was coming and going in any part of his/her body, except around the eyes, nose, mouth and in the diaper area, during his/her first 12 months of life?”.9

The EISL questionnaire also includes questions about eating certain foods during pregnancy (never or occasionally, once or twice a week and three or more times a week). The score of the Mediterranean diet used in this study is based on the score previously constructed by Psaltopoulou10 and previously used in other EISL4,6 and ISAAC studies.11–13 Fruit, fish, vegetables, cereals, pasta, rice and potatoes are considered “pro-Mediterranean” food components and are classified according to the frequency of their intake; 0 points: never or occasionally, 1 point: 1 or 2 times per week and 2 points: almost every day. Meat, milk and fast food are considered “anti-Mediterranean” food components and are scored inversely. Mothers with a higher score had a higher adherence to the Mediterranean diet.11

As olive oil was not included in the above-mentioned food-frequency questionnaire, its consumption was assessed with the question “What is usually used in the household for frying?” (olive oil, butter, margarine, other oil).

A sensitivity analysis was conducted excluding those subjects with six or more missing values in the food frequency questionnaire during pregnancy to assess the robustness of the findings. Mothers who did not answer or did not know the consumption frequency were considered missing.

The study of the association of the different food consumption and Mediterranean diet with wheezing, recurrent wheezing and eczema was performed using different models of unconditional logistic regression to obtain adjusted prevalence odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI).

The statistical analyses were performed with the software SPSS 20.0 (IBM Corp.) and STATA version 13.0 (StataCorp LP).

The study was approved by the Management of Primary Care of Navarre's Health Service and the Scientific Ethic Committee of University of Murcia.

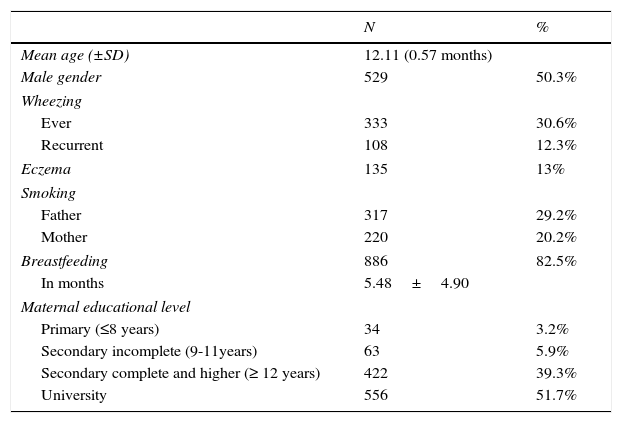

ResultsA total of 1087 questionnaires were answered. The prevalence of wheezing in the first year was 30.6%, recurrent wheezing was 12.3% and eczema 13% (Table 1). Most of the questionnaires were completed by the mother (79.9%) or both parents (15.8%).

Characteristics of the subjects and prevalence of wheezing and eczema.

| N | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Mean age (±SD) | 12.11 (0.57 months) | |

| Male gender | 529 | 50.3% |

| Wheezing | ||

| Ever | 333 | 30.6% |

| Recurrent | 108 | 12.3% |

| Eczema | 135 | 13% |

| Smoking | ||

| Father | 317 | 29.2% |

| Mother | 220 | 20.2% |

| Breastfeeding | 886 | 82.5% |

| In months | 5.48±4.90 | |

| Maternal educational level | ||

| Primary (≤8 years) | 34 | 3.2% |

| Secondary incomplete (9-11years) | 63 | 5.9% |

| Secondary complete and higher (≥ 12 years) | 422 | 39.3% |

| University | 556 | 51.7% |

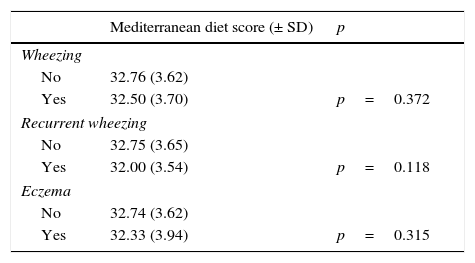

No association was found between good adherence to the Mediterranean diet during pregnancy and the development of wheezing, recurrent wheezing and eczema. However, mothers whose infants had wheezing, recurrent wheezing or eczema had a slightly lower adherence to Mediterranean diet (Table 2).

Adherence to Mediterranean diet during pregnancy of mothers of children with and without wheezing, recurrent wheezing and eczema in children of 12–15 months.

| Mediterranean diet score (± SD) | p | |

|---|---|---|

| Wheezing | ||

| No | 32.76 (3.62) | |

| Yes | 32.50 (3.70) | p=0.372 |

| Recurrent wheezing | ||

| No | 32.75 (3.65) | |

| Yes | 32.00 (3.54) | p=0.118 |

| Eczema | ||

| No | 32.74 (3.62) | |

| Yes | 32.33 (3.94) | p=0.315 |

When the sensitivity analysis was performed, the results did not change substantially. Again, no association was detected between higher adherence to Mediterranean diet and wheezing (p=0.348), nor recurrent wheezing (p=0.116), or eczema (p=0.330) in the offspring.

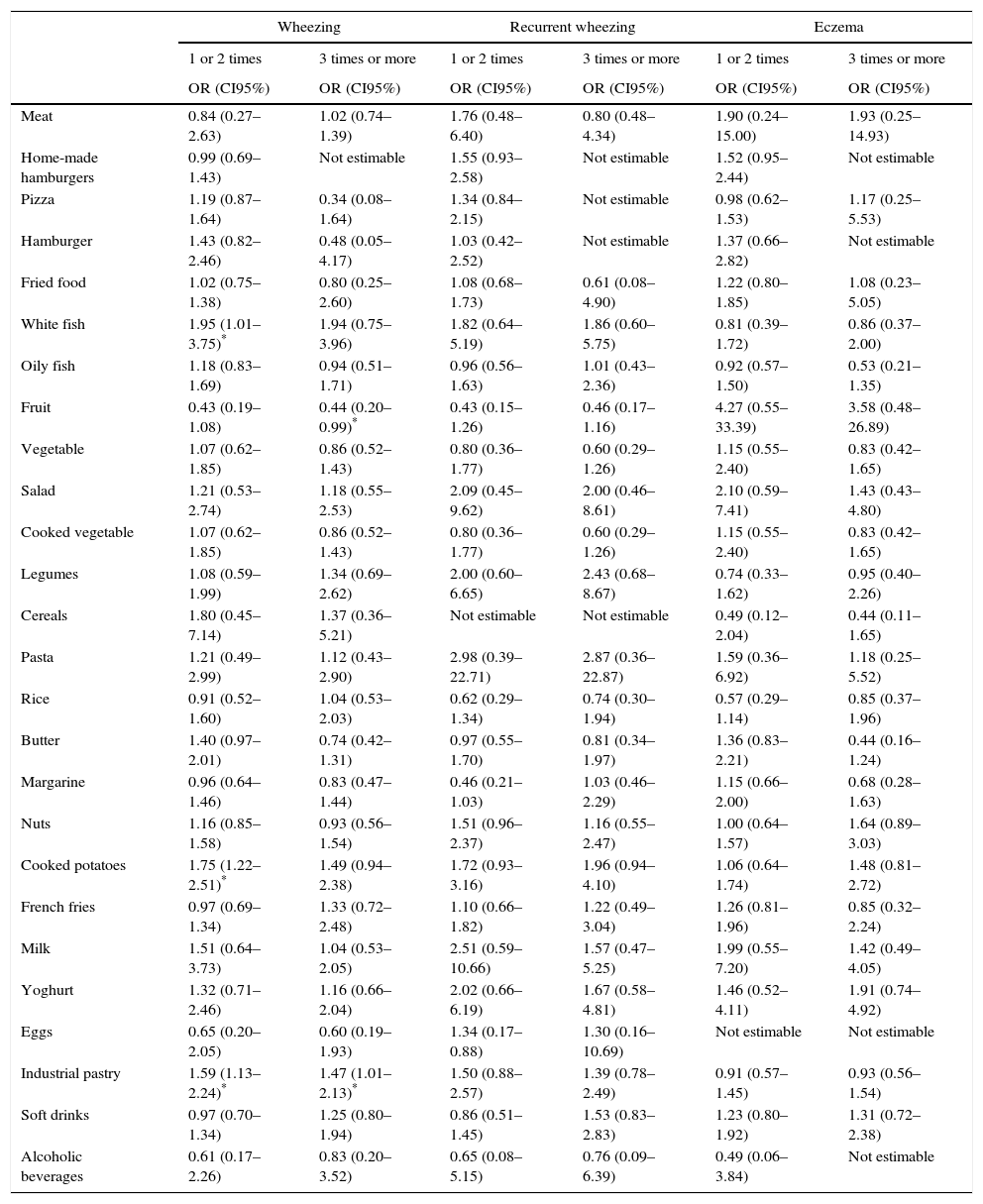

The consumption once or twice a week of white fish, cooked potatoes and industrial pastry and the consumption more than three times a week of industrial pastry during pregnancy increases the risk of “wheezing” at 12 months. Instead, the high consumption more than three times a week of fruit during the pregnancy has a protective effect against “wheezing” in 12-month-old infants. No statistically significant differences were observed between food intake during pregnancy and “recurrent wheeze” (Table 3).

Association between wheezing, recurrent wheezing and eczema and food consumption.

| Wheezing | Recurrent wheezing | Eczema | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 or 2 times | 3 times or more | 1 or 2 times | 3 times or more | 1 or 2 times | 3 times or more | |

| OR (CI95%) | OR (CI95%) | OR (CI95%) | OR (CI95%) | OR (CI95%) | OR (CI95%) | |

| Meat | 0.84 (0.27–2.63) | 1.02 (0.74–1.39) | 1.76 (0.48–6.40) | 0.80 (0.48–4.34) | 1.90 (0.24–15.00) | 1.93 (0.25–14.93) |

| Home-made hamburgers | 0.99 (0.69–1.43) | Not estimable | 1.55 (0.93–2.58) | Not estimable | 1.52 (0.95–2.44) | Not estimable |

| Pizza | 1.19 (0.87–1.64) | 0.34 (0.08–1.64) | 1.34 (0.84–2.15) | Not estimable | 0.98 (0.62–1.53) | 1.17 (0.25–5.53) |

| Hamburger | 1.43 (0.82–2.46) | 0.48 (0.05–4.17) | 1.03 (0.42–2.52) | Not estimable | 1.37 (0.66–2.82) | Not estimable |

| Fried food | 1.02 (0.75–1.38) | 0.80 (0.25–2.60) | 1.08 (0.68–1.73) | 0.61 (0.08–4.90) | 1.22 (0.80–1.85) | 1.08 (0.23–5.05) |

| White fish | 1.95 (1.01–3.75)* | 1.94 (0.75–3.96) | 1.82 (0.64–5.19) | 1.86 (0.60–5.75) | 0.81 (0.39–1.72) | 0.86 (0.37–2.00) |

| Oily fish | 1.18 (0.83–1.69) | 0.94 (0.51–1.71) | 0.96 (0.56–1.63) | 1.01 (0.43–2.36) | 0.92 (0.57–1.50) | 0.53 (0.21–1.35) |

| Fruit | 0.43 (0.19–1.08) | 0.44 (0.20–0.99)* | 0.43 (0.15–1.26) | 0.46 (0.17–1.16) | 4.27 (0.55–33.39) | 3.58 (0.48–26.89) |

| Vegetable | 1.07 (0.62–1.85) | 0.86 (0.52–1.43) | 0.80 (0.36–1.77) | 0.60 (0.29–1.26) | 1.15 (0.55–2.40) | 0.83 (0.42–1.65) |

| Salad | 1.21 (0.53–2.74) | 1.18 (0.55–2.53) | 2.09 (0.45–9.62) | 2.00 (0.46–8.61) | 2.10 (0.59–7.41) | 1.43 (0.43–4.80) |

| Cooked vegetable | 1.07 (0.62–1.85) | 0.86 (0.52–1.43) | 0.80 (0.36–1.77) | 0.60 (0.29–1.26) | 1.15 (0.55–2.40) | 0.83 (0.42–1.65) |

| Legumes | 1.08 (0.59–1.99) | 1.34 (0.69–2.62) | 2.00 (0.60–6.65) | 2.43 (0.68–8.67) | 0.74 (0.33–1.62) | 0.95 (0.40–2.26) |

| Cereals | 1.80 (0.45–7.14) | 1.37 (0.36–5.21) | Not estimable | Not estimable | 0.49 (0.12–2.04) | 0.44 (0.11–1.65) |

| Pasta | 1.21 (0.49–2.99) | 1.12 (0.43–2.90) | 2.98 (0.39–22.71) | 2.87 (0.36–22.87) | 1.59 (0.36–6.92) | 1.18 (0.25–5.52) |

| Rice | 0.91 (0.52–1.60) | 1.04 (0.53–2.03) | 0.62 (0.29–1.34) | 0.74 (0.30–1.94) | 0.57 (0.29–1.14) | 0.85 (0.37–1.96) |

| Butter | 1.40 (0.97–2.01) | 0.74 (0.42–1.31) | 0.97 (0.55–1.70) | 0.81 (0.34–1.97) | 1.36 (0.83–2.21) | 0.44 (0.16–1.24) |

| Margarine | 0.96 (0.64–1.46) | 0.83 (0.47–1.44) | 0.46 (0.21–1.03) | 1.03 (0.46–2.29) | 1.15 (0.66–2.00) | 0.68 (0.28–1.63) |

| Nuts | 1.16 (0.85–1.58) | 0.93 (0.56–1.54) | 1.51 (0.96–2.37) | 1.16 (0.55–2.47) | 1.00 (0.64–1.57) | 1.64 (0.89–3.03) |

| Cooked potatoes | 1.75 (1.22–2.51)* | 1.49 (0.94–2.38) | 1.72 (0.93–3.16) | 1.96 (0.94–4.10) | 1.06 (0.64–1.74) | 1.48 (0.81–2.72) |

| French fries | 0.97 (0.69–1.34) | 1.33 (0.72–2.48) | 1.10 (0.66–1.82) | 1.22 (0.49–3.04) | 1.26 (0.81–1.96) | 0.85 (0.32–2.24) |

| Milk | 1.51 (0.64–3.73) | 1.04 (0.53–2.05) | 2.51 (0.59–10.66) | 1.57 (0.47–5.25) | 1.99 (0.55–7.20) | 1.42 (0.49–4.05) |

| Yoghurt | 1.32 (0.71–2.46) | 1.16 (0.66–2.04) | 2.02 (0.66–6.19) | 1.67 (0.58–4.81) | 1.46 (0.52–4.11) | 1.91 (0.74–4.92) |

| Eggs | 0.65 (0.20–2.05) | 0.60 (0.19–1.93) | 1.34 (0.17–0.88) | 1.30 (0.16–10.69) | Not estimable | Not estimable |

| Industrial pastry | 1.59 (1.13–2.24)* | 1.47 (1.01–2.13)* | 1.50 (0.88–2.57) | 1.39 (0.78–2.49) | 0.91 (0.57–1.45) | 0.93 (0.56–1.54) |

| Soft drinks | 0.97 (0.70–1.34) | 1.25 (0.80–1.94) | 0.86 (0.51–1.45) | 1.53 (0.83–2.83) | 1.23 (0.80–1.92) | 1.31 (0.72–2.38) |

| Alcoholic beverages | 0.61 (0.17–2.26) | 0.83 (0.20–3.52) | 0.65 (0.08–5.15) | 0.76 (0.09–6.39) | 0.49 (0.06–3.84) | Not estimable |

Data are OR (95% CI) and are adjusted for age, gender, breastfeeding, mother education and parental smoking taking as reference no consumption.

Cooking with olive oil was not significantly related with wheezing (p=0.475) nor recurrent wheezing (p=0.396), but infants whose mothers usually cooked with olive oil showed a decreased risk for eczema (OR=0.39; 95% CI 0.21–0.74).

No statistically significant differences were observed between the consumption of any food during pregnancy and the presence of eczema at 12 months (Table 3).

DiscussionThe present study showed that the consumption of Mediterranean diet during pregnancy did not have a protective effect for wheezing, recurrent wheezing or eczema. However, the maternal consumption of white fish, industrial pastry and cooked potatoes increased the risk of wheezing at 12 months of the infant. On the other hand, we found that high fruit consumption during pregnancy had a protective effect only against wheezing in infants. Finally, there was not an association between food consumption during pregnancy and eczema.

The Mediterranean diet is one of the most healthful eating patterns that are known.10 Pre-natal life is a critical period in the development of the child's immune system. Maternal diet during pregnancy has been proposed as a risk factor for the development of wheezing and allergic diseases.5 To date, few prospective studies have evaluated the effect of the Mediterranean diet and the development of asthma observing inconsistent findings.5,14 A recent systematic review described inconsistent or non-significant evidence for an association between maternal dietary patterns during pregnancy and asthma and other atopic conditions in childhood.3 However, a previous systematic review showed that the adherence to a Mediterranean diet may have a protective effect for wheeze and atopy.15

Analysing the frequency of consumption of different foods in greater detail, we noted that the consumption of white fish, cooked potatoes and industrial pastries during pregnancy is associated with “wheezing” at 12 months, whereas high fruit consumption has a protective effect. These results are consistent with previous studies.4,5,16 Several studies have analysed the different food groups and food consumption during pregnancy and its relation to asthma symptoms.

Fish is rich in n-3 PUFAs which are thought to have anti-inflammatory effects through their effects on eicosanoids synthesis,17 but the influence of fish intake and its relationship with the development of asthma or allergic diseases is inconsistent. One study found no relationship between fish consumption and the development of wheezing18; another study observed a protective effect of oily fish but an increased risk with the consumption of fried fish.19 Other studies described a relationship between fish consumption and a protective effect against the development of asthma16,20,21 and allergic disease.16 This inconclusive data on the intake of fish may be due to the fact that the type of cooking of the fish has not been taken into account since it is known that cooking with olive oil has a protective effect against wheezing.6

Fruits and vegetables contain antioxidants and other biologically active factors that may contribute to a favourable effect against asthma and other inflammatory diseases. Vitamin C, β-carotene, magnesium, and selenium are associated with a reduction in the prevalence of asthma and can prevent or limit an inflammatory response in the airway.17,22,23

Different studies have evaluated the effect of Mediterranean diet and food consumption and eczema, without finding a relationship between them.4,5,20 Although there are some studies that have observed that the high intake of dairy products24 may reduce the risk of infantile eczema and that high fast food consumption by mothers can increase the risk of dermatitis,4 although we have not been able to find these relationships.

Olive oil is considered the principal source of fat in the Mediterranean diet.25 Previous investigations evidenced that using olive oil during pregnancy for cooking or dressing salads have a protective effect for infant wheezing during the first year of life.6 In this study, using olive oil for cooking during infant's first year of life only showed an inverse relationship with infant eczema. We presumed that mothers who usually cooked with olive oil throughout the infant's first year of life also did so during pregnancy. Our findings should be interpreted with caution, because neither consumption frequency nor consumed quantity was assessed.

We recognise limitations in our study. The adherence to Mediterranean diet of mothers of children with and without wheezing, recurrent wheezing and eczema was very similar; this could underlie a memory bias and an overestimation of the adherence to the Mediterranean diet could be present as the data on food frequency during pregnancy were collected when the child was 12 months old. Another plausible reason that may explain the observed higher values of adherence to the Mediterranean dietary pattern could be the food components included and measurement scales and score used, which might differ from other studies, and explain the variability.26 In addition, only the frequency of food consumption was asked and not the consumed quantities so any extrapolation on the daily intake must be done with caution. On the other hand, it is known that the phenotype of wheeze in the first year of life is complex, as episodes of wheezing are associated to viral respiratory illnesses and not with asthma, thus this result could reflect the effect of the Mediterranean diet on viral wheezing in early life.

In conclusion, greater adherence to the Mediterranean diet during pregnancy did not show any significant association with either infant wheezing or eczema. Frequent consumption of fruit during pregnancy should be promoted among pregnant women due to its protective effects against wheezing in infants. Further studies with more specific food-frequency questionnaires are needed to identify which dietary patterns during pregnancy could prevent wheezing and eczema in toddlers.

Ethical disclosuresConfidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work centre on the publication of patient data and that all the patients included in the study have received sufficient information and have given their informed consent in writing to participate in that study.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained the informed consent of the patients and/or subjects.

Protection of human subjects and animals in researchThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this investigation.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Research grant from Carlos III Institute, Spanish Ministry of Health and Consumer Affairs, Ref PI 050918; Research grant from the Department of Health, Government of Navarra, Spain, Ref 6106.