Food protein-induced allergic proctocolitis is a frequent cause of rectal bleeding in infants. Characteristics of infants with multiple food allergies have not been defined.

ObjectiveThis study aimed to identify characteristics of infants with proctocolitis and compare infants with single and multiple food allergies.

MethodsA total of 132 infants with proctocolitis were evaluated retrospectively. All of the infants were diagnosed by a paediatric allergist and/or a paediatric gastroenterologist according to guidelines. Clinical features of the infants, as well as results of a complete blood count, skin prick test, specific immunoglobulin E, and stool examinations or colonoscopy were recorded.

ResultsCow's milk (97.7%) was the most common allergen, followed by egg (22%). Forty-five (34.1%) infants had allergies to more than one food. Infants with multiple food allergies had a higher eosinophil count (613±631.2 vs. 375±291.9) and a higher frequency of positive specific IgE and/or positive skin prick test results than that of patients with a single food allergy. Most of the patients whose symptoms persisted after two years of age had multiple food allergies.

ConclusionsThere is no difference in clinical presentations between infants with single and multiple food allergies. However, infants with multiple food allergies have a high blood total eosinophil count and are more likely to have a positive skin prick test and/or positive specific IgE results.

Food protein-induced proctocolitis (FPIAP) is frequent in infants and has a transient course. Otherwise healthy infants with FPIAP usually have streaks of blood mixed with mucus in the stool.1,2 The exact prevalence of FPIAP is unknown and its estimated prevalence ranges from 18 to 64% in infants with rectal bleeding.3–5

Diagnosis of FPIAP is based on clinical manifestations. Tests that identify the offending food proteins are lacking. Specific immunoglobulin E (sIgE) levels and the skin prick test (SPT) have limited assistance in diagnosis.6,7 Usually negative or slightly positive test results for FPIAP are obtained.8

Definitive diagnosis of FPIAP is confirmed by oral food challenge tests. These tests are performed after complete resolution of symptoms by an elimination diet or switching to a hydrolysed hypoallergenic/amino acid-based formula.9,10 Cow's milk protein is initially eliminated from the infant and mother (if breastfeeding), and symptoms typically resolve within 72–96h.1,11,12 If bloody stool or other complaints persist, eliminating common allergens, including soy, egg or other suspected foods, from the diet is considered.1 When the history is convincing and the infant responds to an elimination diet, there is no need for further invasive examinations.13

Characteristics of infants with proctocolitis have been defined. However, characteristics of these infants with multiple food allergies have not been described.7,14,15 Therefore, this study aimed to identify characteristics of infants with FPIAP and compare infants with single and multiple food allergies.

Materials and methodsThis study comprised 132 infants who were diagnosed with FPIAP in paediatric allergy and/or paediatric gastroenterology outpatient clinics between April 2011 and December 2014. We recorded age at onset of symptoms, age at diagnosis, initial symptoms, positive physical examination findings, atopic history, family history of atopy or asthma, allergenic food(s), whether the infant had measurement of total IgE and sIgE levels and a skin prick test performed (cow's milk, egg, wheat, peanut, soy, negative, histamine, and any other suspected food), leucocyte, eosinophil, and thrombocyte counts, stool examination results, and whether the infant had histopathological findings from colonoscopy.

Infections and other causes of rectal bleeding, such as invagination, volvulus, Hirschsprung's disease, and necrotising enterocolitis, were excluded. Definitive diagnosis of FPIAP depended on the medical history, small and bright red rectal bleeding with mucus in an otherwise healthy neonate or infant, and oral food challenges (disappearance of rectal bleeding after an elimination diet and recurrence of rectal bleeding after administration of the offending food).9,10

At enrolment if SPT/sIgE results were negative, all the breastfeeding mothers as well as infants with supplementary feeding initially received a cow's milk elimination diet. Infant formulas were changed with an amino-acid based formula. If the complaints did not resolve in two weeks, additional offending foods were examined and eliminated from the diet of both the breastfeeding mother and/or the infant with supplementary feeding. If SPT/sIgE results were positive, that food was initially eliminated from the diet. Egg elimination was the second eliminated food from the breastfeeding mother and the infant if tests were negative. Mothers of exclusively breastfed infants with MFA were multiple restricted and these carried on in the infant.

If the complaints resolved after two weeks of a symptom-free period a food challenge was performed to determine recurrence of symptoms. We performed food challenge first to breastfeeding mother then to infant with supplementary feeding after two weeks of symptom free intervals.

If rectal bleeding or symptoms of proctocolitis did not recover with an elimination diet, endoscopic evaluation was performed to confirm the diagnosis and to exclude other reasons of rectal bleeding by a paediatric gastroenterologist with a videocolonoscope (Olympus®, Tokyo, Japan). Biopsy specimens were taken from areas of lesions and a histological examination was performed by a pathologist.

A food challenge to an open diet was performed in allergic patients with proctocolitis after a six-month diet as early as nine months of age. Challenge protocols were performed based on a food allergy work group report and EAACI position paper.16,17 If the provocation test was negative, patients continued to receive the challenged food at home. Their parents were informed about late-phase reactions and were asked to return to the elimination diet if any of these reactions occurred. At the end of one week, a phone call was arranged with mothers who were asked if the infants had had any symptoms of proctocolitis. In August 2015, we performed a telephone interview of all the families of patients and questioned them about their children's food allergies.

This study was approved by Baskent University Institutional Review Board (project no: KA16/66). Oral informed consent was obtained from the families of the study participants.

Statistical analysisData were analysed using SPSS 17.0 statistical software (SSPS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The results of statistical analysis are expressed as the number of observations (n) and mean±standard deviation (SD). Shapiro–Wilk's test was used to assess the normality of distribution of the variables. Levene's test was used to assess the homogeneity of variance among the groups. Comparisons of group means were performed with the Student's t test. The chi-squared test was used for comparison of frequencies. A p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

ResultsA total of 132 infants (63 males, 69 females) were included. Cow's milk (n=129, 97.7%) was the most common allergen, followed by egg (n=29, 22%). Twenty-six (19.7%) infants had both milk and egg allergies and three infants had only an egg allergy. Eleven infants had hazelnut and peanut, nine had wheat, five had fish, two had lentil, two had sesame, one had potato, one had corn, and one had spinach and rice allergies.

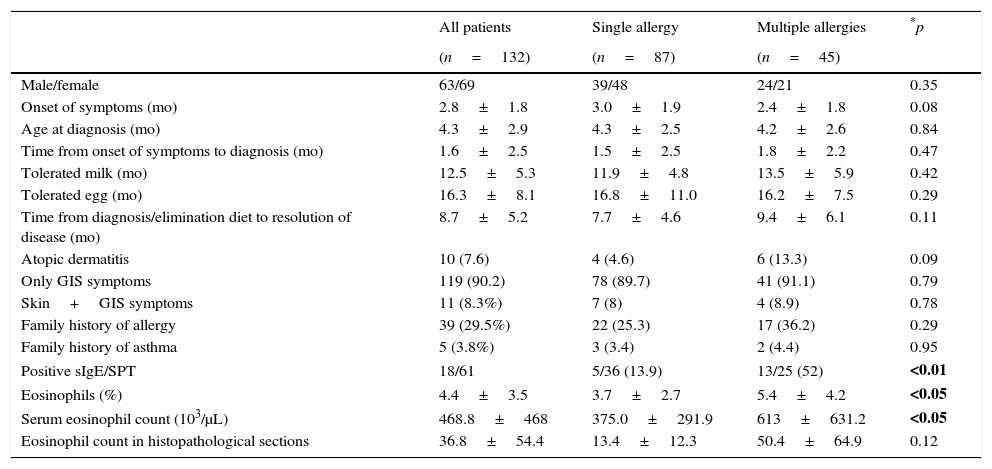

Eighty-seven (65.9%) infants had an allergy to one food, whereas 45 (34.1%) infants had allergies to more than one food (Table 1). Infants with multiple food allergies had a higher eosinophil count than those with a single food allergy (613±631.2 vs. 375±291.9, p<0.05).

Characteristics of infants with FPIAP.

| All patients | Single allergy | Multiple allergies | *p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n=132) | (n=87) | (n=45) | ||

| Male/female | 63/69 | 39/48 | 24/21 | 0.35 |

| Onset of symptoms (mo) | 2.8±1.8 | 3.0±1.9 | 2.4±1.8 | 0.08 |

| Age at diagnosis (mo) | 4.3±2.9 | 4.3±2.5 | 4.2±2.6 | 0.84 |

| Time from onset of symptoms to diagnosis (mo) | 1.6±2.5 | 1.5±2.5 | 1.8±2.2 | 0.47 |

| Tolerated milk (mo) | 12.5±5.3 | 11.9±4.8 | 13.5±5.9 | 0.42 |

| Tolerated egg (mo) | 16.3±8.1 | 16.8±11.0 | 16.2±7.5 | 0.29 |

| Time from diagnosis/elimination diet to resolution of disease (mo) | 8.7±5.2 | 7.7±4.6 | 9.4±6.1 | 0.11 |

| Atopic dermatitis | 10 (7.6) | 4 (4.6) | 6 (13.3) | 0.09 |

| Only GIS symptoms | 119 (90.2) | 78 (89.7) | 41 (91.1) | 0.79 |

| Skin+GIS symptoms | 11 (8.3%) | 7 (8) | 4 (8.9) | 0.78 |

| Family history of allergy | 39 (29.5%) | 22 (25.3) | 17 (36.2) | 0.29 |

| Family history of asthma | 5 (3.8%) | 3 (3.4) | 2 (4.4) | 0.95 |

| Positive sIgE/SPT | 18/61 | 5/36 (13.9) | 13/25 (52) | <0.01 |

| Eosinophils (%) | 4.4±3.5 | 3.7±2.7 | 5.4±4.2 | <0.05 |

| Serum eosinophil count (103/μL) | 468.8±468 | 375.0±291.9 | 613±631.2 | <0.05 |

| Eosinophil count in histopathological sections | 36.8±54.4 | 13.4±12.3 | 50.4±64.9 | 0.12 |

GIS: gastrointestinal system; mo: months; sIgE: specific immunoglobulin E; SPT: skin prick test.

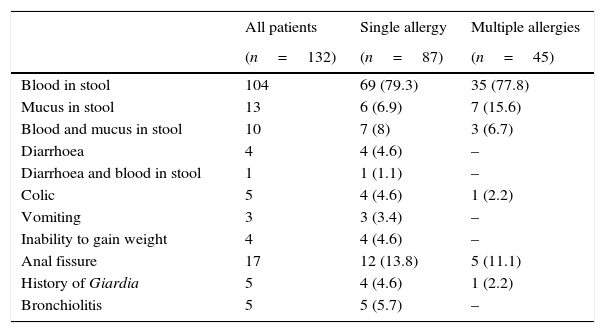

Age of onset of symptoms ranged from two days to 11 months (mean age, 2.8±1.8 months). The most common clinical manifestation was bloody stool (86.4%). A total of 115 patients had stool mixed with blood and 23 had stool with mucus (Table 2). Atopic dermatitis was found in 10 (7.6%) and anal fissure was found in 17 (12.9%) children. The clinical features of infants are shown in Table 2. At the time of the first symptoms, 90 (68.2%) infants were exclusively breastfed and 34/90 had multiple food allergies. Ten exclusively breastfed patients (five had multiple food allergies) had colonoscopy.

Clinical features of infants with FPIAP.

| All patients | Single allergy | Multiple allergies | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (n=132) | (n=87) | (n=45) | |

| Blood in stool | 104 | 69 (79.3) | 35 (77.8) |

| Mucus in stool | 13 | 6 (6.9) | 7 (15.6) |

| Blood and mucus in stool | 10 | 7 (8) | 3 (6.7) |

| Diarrhoea | 4 | 4 (4.6) | – |

| Diarrhoea and blood in stool | 1 | 1 (1.1) | – |

| Colic | 5 | 4 (4.6) | 1 (2.2) |

| Vomiting | 3 | 3 (3.4) | – |

| Inability to gain weight | 4 | 4 (4.6) | – |

| Anal fissure | 17 | 12 (13.8) | 5 (11.1) |

| History of Giardia | 5 | 4 (4.6) | 1 (2.2) |

| Bronchiolitis | 5 | 5 (5.7) | – |

Values are number (%) unless otherwise indicated.

Symptoms began in 11 (8.3%) new-borns. All had a milk allergy, seven (63.6%) were exclusively breastfed, and six (54.5%) had multiple food allergies. We compared these new-borns with infants whose symptoms had started after the new-born period. There were no differences in the time from initial symptoms to diagnosis, time to resolution of disease, frequency of multiple food allergies, eosinophil count and percentage, total IgE levels, sIgE levels, and SPT results between these age groups.

The SPT was performed in 37 (28%) patients and sIgE levels were measured in 51 (38.6%) patients. Patients with a positive SPT and/or sIgE results (n=18) were compared with those with negative results (n=44). Infants with multiple food allergies had a higher frequency of sIgE and/or SPT-positive results than those with a single food allergy (p<0.05).

Thirteen patients (35%) had positive SPT results. Thirty-four patients had oral food challenge (OFC) proven milk allergy and five (14.7%) had positive SPT result for milk. Eighteen patients had OFC proven egg allergy and 10 (55.5%) had positive SPT result for egg. Fifty-one patients had sIgE for milk and egg; 48 patients had OFC proven milk allergy and five (10.4%) of them had positive milk sIgE result. Twenty-fine patients had OFC proven egg allergy and six (24%) had positive egg sIgE result.

When male and female infants were compared, there was no difference in age at the initial complaint, age at diagnosis, time from initial symptoms to diagnosis, time to resolution of disease, eosinophil count and percentage, total IgE levels, sIgE levels, and SPT results.

Twenty (15.2%) children (mean age at diagnosis, 4.8±3 months) underwent colonoscopy with biopsy for further analysis. The time of onset of symptoms was similar in colonoscopy (+) and (−) infants (3±2.9 vs. 2.7±1.6 months). The time from symptoms to diagnosis was significantly higher in colonoscopy (+) infants than in colonoscopy (−) infants (2.3±2.8 vs. 1.3±1.4, p<0.01). Twelve (60%) of the patients who had colonoscopy performed had multiple food allergies. Patients with multiple food allergies had significantly more colonoscopies performed than those with a single food allergy (p<0.01). Leucocyte counts were significantly higher in colonoscopy (+) infants (12,282.1±4676.9) than in colonoscopy (−) infants (9974.6±3257.8, p<0.05). Fifteen (75%) of the patients who had colonoscopy performed showed eosinophilic infiltration and seven of them had lymphoid aggregates in histopathological sections. The mean eosinophil count in tissue specimens was 35±53.6/40 high power field (HPF). The mean eosinophil count in histopathological sections was 13.4±12.3/40 HPF in children with a single allergy (n=8) and 50.4±64.9/40 HPF in those with multiple allergies (n=12, p=0.12).

Thirty-eight (28%) of the patients were followed with regular visits and performed food challenges in the paediatric allergy outpatient clinic. Eighty (60.6%) patients were challenged the offending food at home. Patients tolerated milk at a mean age of 12.5±5.3 months and tolerated egg at a mean age of 16.3±8.1 months (Table 1). FPIAP persisted in 14 (10.6%, 11 had multiple food allergies) patients after two years old. In their follow-up, eight patients tolerated offending food(s).

Frequency of remission of food allergy by two years of age is higher in infants with single food allergy (94%) compared to infants with multiple food allergies (81.6%) (p=0.03).

An elimination diet in six (4.5%) patients (five had multiple food allergies) was still continued for at least one food in August 2015. The ages of these patients ranged from 20 to 72 months (mean: 38.3±19.2 months). Symptoms to egg persisted in two patients; those to nuts in two patients; and those to milk, egg, cereals, and nuts in two patients.

DiscussionAllergic proctocolitis is a frequent cause of rectal bleeding in infants and considered as one of the major causes of colitis at ages younger than one year. In this study, we evaluated characteristics of infants with allergic proctocolitis. Unlike other studies, we compared infants with single and multiple food allergies and examined if any differential features could be defined. The total blood eosinophil count and the percentage of eosinophils and sIgE/SPT results showed significant differences between the groups. If infants have multiple food allergies, they appear to be more likely to have a high blood eosinophil count and positive sIgE/SPT results. Similar to our study, Ozbek et al. performed a study in patients with food allergies that developed after liver transplantation. They suggested that the eosinophil count reached a high level when children developed food allergies.18 In their study, most of the liver-transplanted children had multiple food allergies at the time of diagnosis.18

Breastfed infants react to food proteins that are consumed by their mother.19,20 In our study, 90 patients were exclusively breast fed at the time of the first symptoms and more than one-third of them had multiple food allergies. Elimination of offending food from the mother's diet usually results in gradual resolution of symptoms in infants and permits continuation of breastfeeding.1,2,12,21 Rarely, an extensively hydrolysed formula or an amino acid-based formula may be necessary for resolution of bleeding.22–24 In our study, offending foods were also eliminated from the mother's diet and amino acid-based formulas were recommended to infants if necessary.

The onset of symptoms in FPIAP is usually insidious with a prolonged latent interval between introduction of food protein and appearance of symptoms. If the patient is a breastfed infant with multiple food allergies, determining the allergen can be more difficult. Complaints can continue despite maternal avoidance of the suspected offending foods. However, in the current study, there was no difference in the times from onset of symptoms to diagnosis and from diagnosis to resolution of symptoms between infants with single and multiple food allergies.

The persistence of rectal bleeding despite dietary restrictions may be explained by the inability to remove all sources of the allergen from the diet or by an allergen that has not been identified. Measuring sIgE levels or SPT results has limited assistance in diagnosis of FPIAP and negative or slightly positive test results are usually obtained.6–8 Boonyaviwat and Canani et al. examined children with suspected food allergy-related gastrointestinal symptoms and showed that 14.5% and 45% of patients respectively had positive SPT results.25,26 However, in our study 35% of children with allergic proctocolitis had positive SPT results. Additionally, we found that infants with multiple food allergies had more frequent positive SPT and/or sIgE results than those with a single allergy. Because cow's milk is the most common allergen, an elimination diet with this allergen is usually considered before performing the SPT and/or sIgE measurement. However, if clinicians believe that an infant may have multiple food allergies or if symptoms continue after an elimination diet with cow's milk, the SPT and/or sIgE measurement should be performed.

Infants with FPIAP typically appear well. However, increased gas, intermittent emesis, pain on defecation, or abdominal pain may be observed.27 In our study, five infants had colic, three had intermittent emesis, and four of them were unable to gain weight. Thirteen patients had stool only mixed with mucus and 115 had blood mixed with stool. Rectal bleeding was often attributed to anal fissures.

In our study, the most common allergen was cow's milk followed by egg. However, corn, rice, and soy allergies were not encountered. This finding can be explained by nutritional habits of our infants and their mothers. Kaya et al. showed that symptoms began earlier in boys, and FPIAP persisted in 20% of patients after two years old and may continue for up to five years.24 However, there was no sex difference in our study and FPIAP persisted in 14 (10.6%) patients after two years of age. We observed that most of our patients had multiple food allergies, including egg or nuts, and our oldest patient still had symptoms at six years of age.

Infants with FPIAP occasionally continue to have bleeding despite avoidance of foods. If complaints of an infant persist, colonoscopy may help to confirm the diagnosis or exclude other possible reasons. FPIAP predominantly affects the rectosigmoid and focal eosinophilic infiltrates, as well as lymphoid aggregates, which support the diagnosis of proctocolitis.2,15,28–30 Twenty (15.2%) infants had colonoscopy in our study and most (16/20) of the infants had eosinophilic infiltrates. Additionally, seven of them had lymphoid aggregates in tissue specimens. However, Xanthakos et al. suggested that biopsy findings alone may not be helpful in diagnosing FPIAP.5 Similar to their study, five infants who had colonoscopy performed in our study showed no eosinophils in histopathological sections. However, these infants were diagnosed with FPIAP according to the medical history, elimination diet, and challenge test.

We examined infants who underwent colonoscopy. The time of onset of symptoms was similar between infants who had colonoscopy performed and those who had not. However, the time from symptoms to diagnosis was longer in infants who had colonoscopy performed than in those who had not. Having multiple food allergies and being unable to detect all of the offending foods that cause persisting symptoms can lead to physicians performing colonoscopy.

A limitation of our study was its retrospective design. Not all of the patients had specific IgE or skin tests. However, we had a sufficient number of patients for comparison. Future research is needed to define our results more clearly and to determine why infants with multiple food allergies have a higher eosinophil count than those with a single allergy.

In conclusion, there is no difference in clinical presentations between infants with single and multiple food allergies. However, infants with multiple food allergies have a high blood total eosinophil count and are more likely to have a positive SPT and/or positive sIgE results. If an infant has a high eosinophil count and if symptoms persist after a simple cow's milk elimination diet, physicians may recommend the SPT or sIgE measurements.

Ethical disclosuresConfidentiality of dataThe authors declare that no patient data appears in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained the informed consent of the patients and/or subjects mentioned in the article. The author for correspondence is in possession of this document.

Protection of human subjects and animals in researchThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this investigation.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. The study was approved by Baskent University Institutional Review Board (project no: KA16/66).

This work was performed at Baskent University Faculty of Medicine.