Since early 2000s, atopy patch test (APT) has been used to determine non-IgE and mixed-type food allergies. Previous studies have reported conflicting results about the diagnostic value of APT in food allergies, due to non-standardized methods.

We aimed to determine the diagnostic efficacy of APT compared to open oral food challenge (OFC) in patients diagnosed with cow's milk allergy (CMA) and hen's egg allergy (HEA) manifesting as atopic dermatitis (AD) and gastrointestinal system symptoms.

Materials and methodsIn patients with suspected AD and/or gastrointestinal manifestations due to CMA and HEA, the results of OFC, APT, skin prick test (SPT) and specific IgE (sIgE) were reviewed. Specificity, sensitivity, positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV) and accuracy of sIgE, SPT, APT and SPT+APT were calculated.

ResultsIn total 133 patients with suspected CMA (80) and HEA (53) were included in the study.

In patients with CMA presenting with gastrointestinal symptoms, APT had sensitivity of 9.1%, specificity of 100%, PPV of 100% and NPV of 48.7%. In atopic dermatitis patients, sensitivity of APT was 71.4%, specificity 90.6%, PPV 62.5% and NPV 93.6%.

In patients diagnosed with HEA, the sensitivity, specificity, PPV and NPV values of APT were 72.0%, 78.6%, 47.2% and 75.0%, respectively. In patients diagnosed with HEA presenting with AD, sensitivity of APT was 87.5%, specificity 70.6%, PPV 73.7% and NPV 85.7%. Atopy patch test had lower sensitivity (44.4%) and higher specificity (90.9%) in patients diagnosed with HEA presenting with gastrointestinal symptoms than those presenting with AD.

ConclusionOur study showed that APT provided reliable diagnostic accuracy in atopic dermatitis patients. However, APT had low sensitivity in patients with gastrointestinal symptoms.

Food allergy is an increasing public health issue in the paediatric age group worldwide. The most common allergens responsible for food allergy are cow's milk and hen's egg. During the last decades, the prevalence of cow's milk allergy (CMA) and hen's egg allergy (HEA) appear to have increased.1–3

There are two main immune reaction types in food allergy, i.e. IgE-mediated and non-IgE-mediated. Double-blind, placebo-controlled oral food challenge is the gold standard method for the diagnosis of all types of food allergies.4 However, this is difficult to perform in outpatient clinics or in patients with severe symptoms.

While specific IgE (sIgE) and skin prick test (SPT) are useful for the diagnosis of IgE-mediated reactions, these tests are inappropriate for the non-IgE-mediated or mixed-type immune reactions such as atopic dermatitis, food protein-induced allergic proctocolitis (FPIAP), food protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome (FPIES) and food protein-induced enteropathy (FPE).5

Since the early 2000s, atopy patch test (APT) has been used for the determination of non-IgE and mixed-type food allergies.6 Conflicting results have been reported in previous studies about the diagnostic value of APT in food allergies, due to non-standardized methods.7

In this study, we aimed to determine the diagnostic efficacy of APT compared to open oral food challenge (OFC) in patients diagnosed with CMA and HEA manifesting as atopic dermatitis and gastrointestinal system symptoms. The secondary aim of this study is to identify the variation of diagnostic accuracy of APT in patients with different clinical manifestations.

Materials and methodsStudy populationData were collected from chart reviews. One hundred and seventy-six paediatric patients with suspected atopic dermatitis and gastrointestinal manifestations such as FPIAP, FPIES and FPE due to cow's milk and hen's egg allergy were retrospectively investigated between January 2015-September 2019 at Dokuz Eylül University Pediatric Immunology and Allergy outpatient clinic.

Patients evaluated with OFC, APT, SPT and sIgE were enrolled. Thirty-three patients with missing data of OFC, SPT, APT and specific IgE results were excluded from the study. Food allergy was diagnosed with open OFC.8

One hundred and thirty-three patients aged between three months and five years with suspicion of CMA (80 patients) and HEA (53 patients) were included in the study. Of these, 53 (39.8%) were female and 80 (60.2%) were male. The median age of the study group was eight months [6–12.5].

Atopy patch testOne drop of fresh milk, egg white and yolk was placed into individual IQ Ultimate™ IQ-UL chambers, Chemotechnique MB, Vellinge, Sweden. The volume of each chamber was 32μL and the inner area of the chamber was 64mm2. These chambers were applied with adhesive hypoallergenic tape to the upper part of the patients’ back.

After an application period of 48h, the first evaluation was performed 20mins after removal of the chamber. The second reading was made 24h after the first evaluation (72h after the test started).

Atopy patch test reactions were classified as previously stated.9,10 Reactions expressed as at least 2+ were accepted as positive.

Oral food challenge testAll open OFCs were performed after two weeks of an elimination diet. The OFC was performed in hospital when increased doses of cow's milk or hen's egg were administered. If there were no reactions, then OFC of one serving amount of that food continued for at least two weeks at home with the symptoms being observed by the parents. The OFC was discontinued when a clinical symptom occurred. In the event of adverse reaction, the parents were told to call and visit the investigator as soon as possible. If no clinical symptom was presented, the OFC was considered negative.11

Skin prick testSkin prick test was performed according to the standard procedure in our laboratory. Positive SPTs with commercially available milk and egg white and yolk extracts (Alk-Abello®, Hørsholm, Denmark) were defined as a wheal size at least 3mm greater than the negative controls.

All OFC, APT and SPT procedures were performed and assessed by the same technician and clinician. If patients used antihistamines, systemic corticosteroids or topical steroids for seven days or longer, the tests were cancelled.

Serum sIgESpecific IgE for milk and egg white was evaluated using immunoCAP (Phadia AB®, Uppsala, Sweden). A value ≥0.35kU/L was accepted as a positive result.

Ethical approvalThe study protocol was designed in compliance with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki. This study has been granted approval by the University Research Ethics Board (Ethical number of approval: 2019/25-14).

Statistical analysisCategorical variables (gender, clinical symptoms, positive sIgE, positive SPT and positive APT) were assessed by means of the Chi-square or Fischer's exact tests and expressed as number and percentage. Non-parametric continuous variables (median [25–75 percentile]) such as age were analyzed with Mann–Whitney U test. Specificity, sensitivity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value and accuracy of sIgE, SPT, APT and SPT+APT were calculated using the OFC result as the gold standard.

Data were analyzed with the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) computer software (version 21.0; SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA) and MedCalc v12.5 software. A two-tailed p-value <0.05 was considered significant.

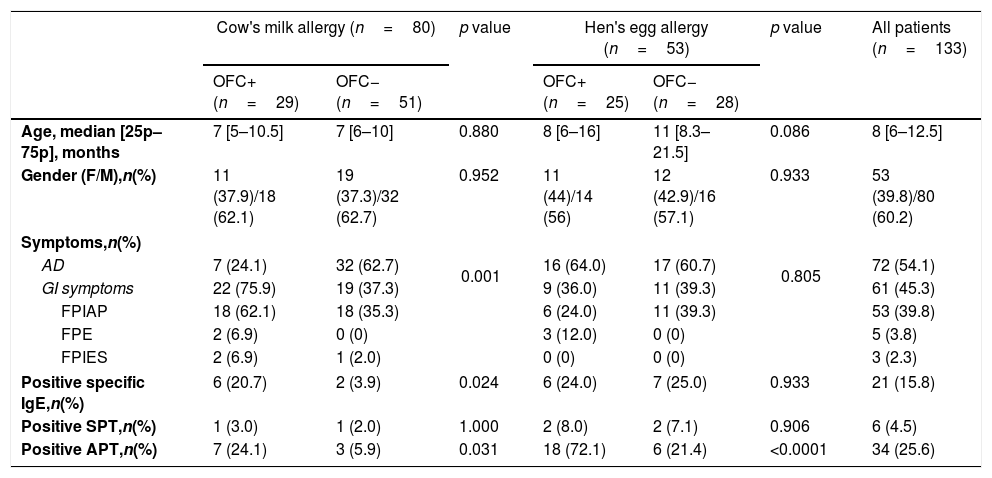

ResultsAtopic dermatitis and gastrointestinal system symptoms (FPIAP, FPIES and FPE) were determined in 72 (54.1%) and 61 (45.9%) patients, respectively. In patients with CMA, OFC was positive in 29 patients (36.3%). From 53 patients, 25 (47.2%) exhibited positive OFC for hen's egg (Table 1). Positive milk-specific IgE and positive APT were more frequently detected in patients with positive OFC for cow's milk than patients with negative OFC for cow's milk (20.7% vs. 3.9%; 24.1% vs. 5.9%). Positive APT was more common in patients with positive OFC for hen's egg (72.1%) than patients with negative OFC for hen's egg (21.4%) (Table 1).

Demographic, clinical and laboratory data of patients with suspected CMA, HEA and the overall study group.

| Cow's milk allergy (n=80) | p value | Hen's egg allergy (n=53) | p value | All patients (n=133) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OFC+ (n=29) | OFC− (n=51) | OFC+ (n=25) | OFC− (n=28) | ||||

| Age, median [25p–75p], months | 7 [5–10.5] | 7 [6–10] | 0.880 | 8 [6–16] | 11 [8.3–21.5] | 0.086 | 8 [6–12.5] |

| Gender (F/M),n(%) | 11 (37.9)/18 (62.1) | 19 (37.3)/32 (62.7) | 0.952 | 11 (44)/14 (56) | 12 (42.9)/16 (57.1) | 0.933 | 53 (39.8)/80 (60.2) |

| Symptoms,n(%) | |||||||

| AD | 7 (24.1) | 32 (62.7) | 0.001 | 16 (64.0) | 17 (60.7) | 0.805 | 72 (54.1) |

| GI symptoms | 22 (75.9) | 19 (37.3) | 9 (36.0) | 11 (39.3) | 61 (45.3) | ||

| FPIAP | 18 (62.1) | 18 (35.3) | 6 (24.0) | 11 (39.3) | 53 (39.8) | ||

| FPE | 2 (6.9) | 0 (0) | 3 (12.0) | 0 (0) | 5 (3.8) | ||

| FPIES | 2 (6.9) | 1 (2.0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (2.3) | ||

| Positive specific IgE,n(%) | 6 (20.7) | 2 (3.9) | 0.024 | 6 (24.0) | 7 (25.0) | 0.933 | 21 (15.8) |

| Positive SPT,n(%) | 1 (3.0) | 1 (2.0) | 1.000 | 2 (8.0) | 2 (7.1) | 0.906 | 6 (4.5) |

| Positive APT,n(%) | 7 (24.1) | 3 (5.9) | 0.031 | 18 (72.1) | 6 (21.4) | <0.0001 | 34 (25.6) |

AD: atopic dermatitis; APT: atopy patch test; F: female; FPIAP: food protein-induced allergic proctocolitis; FPIES: food protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome; FPE: food protein-induced enteropathy; GI: gastrointestinal; M: male; OFC: oral food challenge test; SPT: skin prick test.

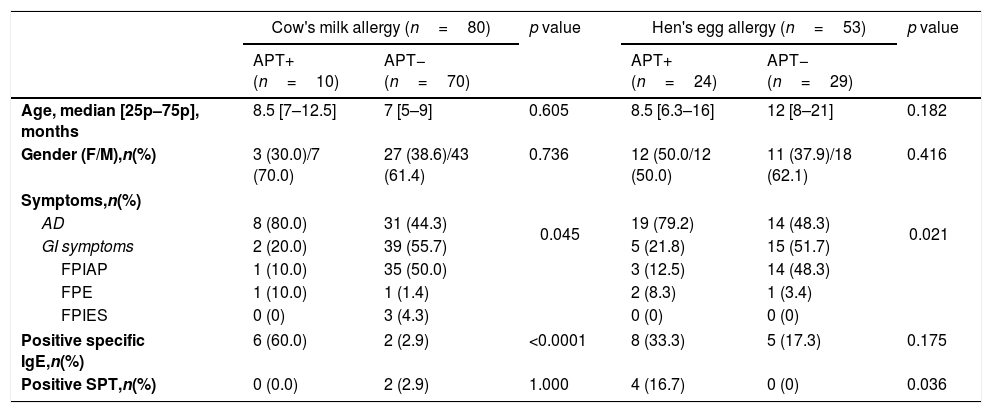

In the comparison of all patients with positive and negative APT, atopic dermatitis was found to be more common in patients with positive APT in both the CMA and HEA groups than patients with negative APT (80% vs. 44.3%, p=0.045; 79.2% vs. 48.3%, p=0.021). On the other hand, in the CMA group the frequency of positive milk-specific IgE was higher in patients with positive APT (60.0%) than that in patients with negative APT (2.9%), and in the HEA group the frequency of positive egg white SPT was higher in patients with positive APT (16.7%) than that in patients with negative APT (0.0%) (Table 2).

Demographic, clinical and laboratory data of patients with suspected CMA and HEA in terms of positive and negative APT.

| Cow's milk allergy (n=80) | p value | Hen's egg allergy (n=53) | p value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| APT+ (n=10) | APT− (n=70) | APT+ (n=24) | APT− (n=29) | |||

| Age, median [25p–75p], months | 8.5 [7–12.5] | 7 [5–9] | 0.605 | 8.5 [6.3–16] | 12 [8–21] | 0.182 |

| Gender (F/M),n(%) | 3 (30.0)/7 (70.0) | 27 (38.6)/43 (61.4) | 0.736 | 12 (50.0/12 (50.0) | 11 (37.9)/18 (62.1) | 0.416 |

| Symptoms,n(%) | ||||||

| AD | 8 (80.0) | 31 (44.3) | 0.045 | 19 (79.2) | 14 (48.3) | 0.021 |

| GI symptoms | 2 (20.0) | 39 (55.7) | 5 (21.8) | 15 (51.7) | ||

| FPIAP | 1 (10.0) | 35 (50.0) | 3 (12.5) | 14 (48.3) | ||

| FPE | 1 (10.0) | 1 (1.4) | 2 (8.3) | 1 (3.4) | ||

| FPIES | 0 (0) | 3 (4.3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||

| Positive specific IgE,n(%) | 6 (60.0) | 2 (2.9) | <0.0001 | 8 (33.3) | 5 (17.3) | 0.175 |

| Positive SPT,n(%) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (2.9) | 1.000 | 4 (16.7) | 0 (0) | 0.036 |

AD: atopic dermatitis; APT: atopy patch test; F: female; FPIAP: food protein-induced allergic proctocolitis; FPIES: food protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome; FPE: food protein-induced enteropathy; GI: gastrointestinal; M: male; SPT: skin prick test.

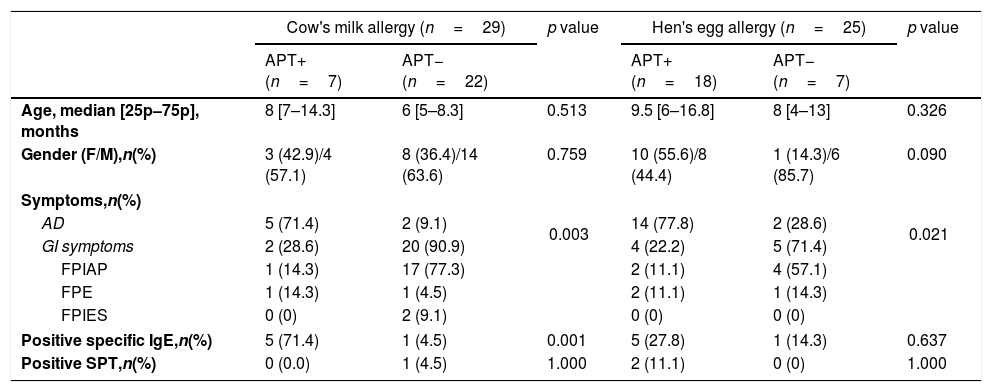

In the analysis of 63 patients with positive OFC for cow's milk or hen's egg, patients with positive APT had a higher rate of presenting with atopic dermatitis than patients with negative APT both in CMA and HEA groups. However, in both CMA and HEA groups, higher specific IgE levels were detected in APT-positive patients, and this difference was statistically significant only in the CMA group (Table 3).

Demographic, clinical and laboratory data of patients with positive OFC for cow's milk or hen's egg in terms of positive and negative APT.

| Cow's milk allergy (n=29) | p value | Hen's egg allergy (n=25) | p value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| APT+ (n=7) | APT− (n=22) | APT+ (n=18) | APT− (n=7) | |||

| Age, median [25p–75p], months | 8 [7–14.3] | 6 [5–8.3] | 0.513 | 9.5 [6–16.8] | 8 [4–13] | 0.326 |

| Gender (F/M),n(%) | 3 (42.9)/4 (57.1) | 8 (36.4)/14 (63.6) | 0.759 | 10 (55.6)/8 (44.4) | 1 (14.3)/6 (85.7) | 0.090 |

| Symptoms,n(%) | ||||||

| AD | 5 (71.4) | 2 (9.1) | 0.003 | 14 (77.8) | 2 (28.6) | 0.021 |

| GI symptoms | 2 (28.6) | 20 (90.9) | 4 (22.2) | 5 (71.4) | ||

| FPIAP | 1 (14.3) | 17 (77.3) | 2 (11.1) | 4 (57.1) | ||

| FPE | 1 (14.3) | 1 (4.5) | 2 (11.1) | 1 (14.3) | ||

| FPIES | 0 (0) | 2 (9.1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||

| Positive specific IgE,n(%) | 5 (71.4) | 1 (4.5) | 0.001 | 5 (27.8) | 1 (14.3) | 0.637 |

| Positive SPT,n(%) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (4.5) | 1.000 | 2 (11.1) | 0 (0) | 1.000 |

AD: atopic dermatitis; APT: atopy patch test; F: female; FPIAP: food protein-induced allergic proctocolitis; FPIES: food protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome; FPE: food protein-induced enteropathy; GI: gastrointestinal; M: male; SPT: skin prick test.

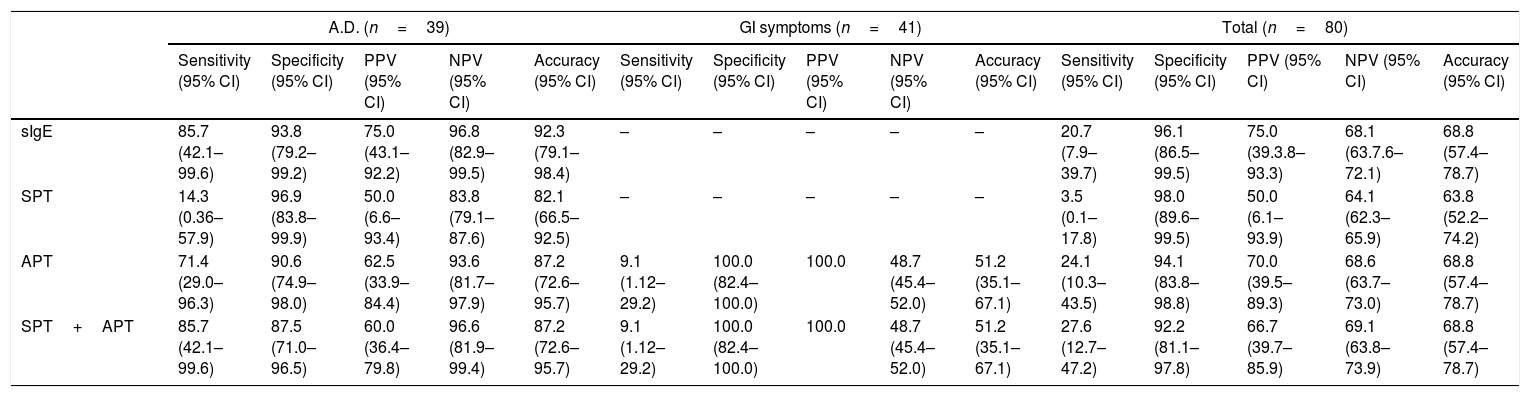

Sensitivity, specificity, PPV, NPV and accuracy of milk-specific IgE, SPT and APT for CMA are presented in Table 4. While SPT had a sensitivity of 3.5%, specificity of 98.0%, PPV of 50.0% and NPV of 64.1% in patients with suspected CMA, the sensitivity, specificity, PPV and NPV values of APT were 27.6%, 92.2%, 66.7% and 69.1%, respectively. When patients diagnosed with CMA were stratified according to clinical findings, APT had a sensitivity of 9.1%, specificity of 100%, PPV of 100% and NPV 48.7% in patients with gastrointestinal symptoms. In patients with atopic dermatitis, APT had a sensitivity of 71.4%, specificity of %90.6, PPV of 62.5% and NPV of 93.6%. While combining APT with SPT improved the sensitivity from 71.4% to 85.7% in patients with atopic dermatitis, diagnostic accuracy did not change in patients with gastrointestinal symptoms. In all patients with gastrointestinal symptoms, non-IgE reaction was detected and none of them had positive milk-specific IgE and SPT; therefore, diagnostic values of egg white-specific IgE and egg white SPT were not assessed (Table 4).

Sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value and accuracy of sIgE, skin prick test, and atopy patch test compared with OFC in cow's milk allergy.

| A.D. (n=39) | GI symptoms (n=41) | Total (n=80) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity (95% CI) | Specificity (95% CI) | PPV (95% CI) | NPV (95% CI) | Accuracy (95% CI) | Sensitivity (95% CI) | Specificity (95% CI) | PPV (95% CI) | NPV (95% CI) | Accuracy (95% CI) | Sensitivity (95% CI) | Specificity (95% CI) | PPV (95% CI) | NPV (95% CI) | Accuracy (95% CI) | |

| sIgE | 85.7 (42.1–99.6) | 93.8 (79.2–99.2) | 75.0 (43.1–92.2) | 96.8 (82.9–99.5) | 92.3 (79.1–98.4) | – | – | – | – | – | 20.7 (7.9–39.7) | 96.1 (86.5–99.5) | 75.0 (39.3.8–93.3) | 68.1 (63.7.6–72.1) | 68.8 (57.4–78.7) |

| SPT | 14.3 (0.36–57.9) | 96.9 (83.8–99.9) | 50.0 (6.6–93.4) | 83.8 (79.1–87.6) | 82.1 (66.5–92.5) | – | – | – | – | – | 3.5 (0.1–17.8) | 98.0 (89.6–99.5) | 50.0 (6.1–93.9) | 64.1 (62.3–65.9) | 63.8 (52.2–74.2) |

| APT | 71.4 (29.0–96.3) | 90.6 (74.9–98.0) | 62.5 (33.9–84.4) | 93.6 (81.7–97.9) | 87.2 (72.6–95.7) | 9.1 (1.12–29.2) | 100.0 (82.4–100.0) | 100.0 | 48.7 (45.4–52.0) | 51.2 (35.1–67.1) | 24.1 (10.3–43.5) | 94.1 (83.8–98.8) | 70.0 (39.5–89.3) | 68.6 (63.7–73.0) | 68.8 (57.4–78.7) |

| SPT+APT | 85.7 (42.1–99.6) | 87.5 (71.0–96.5) | 60.0 (36.4–79.8) | 96.6 (81.9–99.4) | 87.2 (72.6–95.7) | 9.1 (1.12–29.2) | 100.0 (82.4–100.0) | 100.0 | 48.7 (45.4–52.0) | 51.2 (35.1–67.1) | 27.6 (12.7–47.2) | 92.2 (81.1–97.8) | 66.7 (39.7–85.9) | 69.1 (63.8–73.9) | 68.8 (57.4–78.7) |

AD: atopic dermatitis; APT: atopy patch test; GI: gastrointestinal; NPV: negative predictive value; PPV: positive predictive value; SPT: skin prick test.

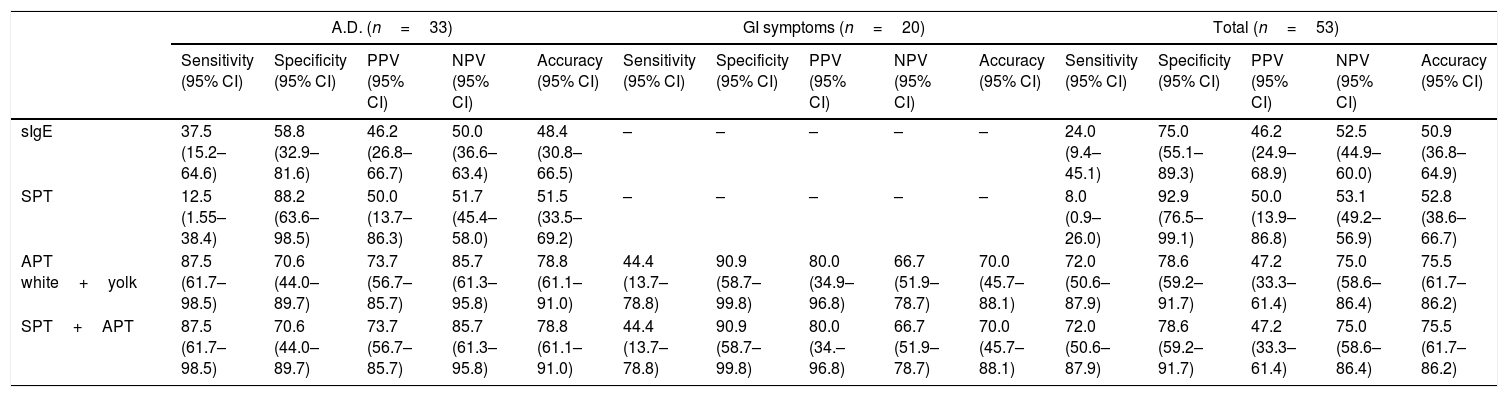

Sensitivity, specificity, PPV, NPV and accuracy of egg white-specific IgE, egg white SPT and APT for HEA are presented in Table 5. While SPT had a sensitivity of 8.0%, specificity of 92.9%, PPV of 50.0% and NPV of 53.1% in patients with suspected HEA, the sensitivity, specificity, PPV and NPV values of APT were 72.0%, 78.6%, 47.2% and 75.0%, respectively. In patients with atopic dermatitis, the sensitivity, specificity, PPV and NPV of APT were 87.5%, 70.6%, 73.7% and 85.7%, respectively. APT had lower sensitivity (44.4%) and higher specificity (90.9%) in patients with gastrointestinal symptoms than that in patients with atopic dermatitis. Combining APT with SPT did not improve the diagnostic accuracy in patients with suspected CMA presenting with atopic dermatitis or gastrointestinal symptoms. In all patients with gastrointestinal symptoms, non-IgE reaction was detected and none of them had positive egg white-specific IgE and egg white SPT; therefore, diagnostic values of egg white-specific IgE and egg white SPT were not calculated (Table 5).

Sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value and accuracy of sIgE, skin prick test and atopy patch test compared with OFC in hen's egg allergy.

| A.D. (n=33) | GI symptoms (n=20) | Total (n=53) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity (95% CI) | Specificity (95% CI) | PPV (95% CI) | NPV (95% CI) | Accuracy (95% CI) | Sensitivity (95% CI) | Specificity (95% CI) | PPV (95% CI) | NPV (95% CI) | Accuracy (95% CI) | Sensitivity (95% CI) | Specificity (95% CI) | PPV (95% CI) | NPV (95% CI) | Accuracy (95% CI) | |

| sIgE | 37.5 (15.2–64.6) | 58.8 (32.9–81.6) | 46.2 (26.8–66.7) | 50.0 (36.6–63.4) | 48.4 (30.8–66.5) | – | – | – | – | – | 24.0 (9.4–45.1) | 75.0 (55.1–89.3) | 46.2 (24.9–68.9) | 52.5 (44.9–60.0) | 50.9 (36.8–64.9) |

| SPT | 12.5 (1.55–38.4) | 88.2 (63.6–98.5) | 50.0 (13.7–86.3) | 51.7 (45.4–58.0) | 51.5 (33.5–69.2) | – | – | – | – | – | 8.0 (0.9–26.0) | 92.9 (76.5–99.1) | 50.0 (13.9–86.8) | 53.1 (49.2–56.9) | 52.8 (38.6–66.7) |

| APT white+yolk | 87.5 (61.7–98.5) | 70.6 (44.0–89.7) | 73.7 (56.7–85.7) | 85.7 (61.3–95.8) | 78.8 (61.1–91.0) | 44.4 (13.7–78.8) | 90.9 (58.7–99.8) | 80.0 (34.9–96.8) | 66.7 (51.9–78.7) | 70.0 (45.7–88.1) | 72.0 (50.6–87.9) | 78.6 (59.2–91.7) | 47.2 (33.3–61.4) | 75.0 (58.6–86.4) | 75.5 (61.7–86.2) |

| SPT+APT | 87.5 (61.7–98.5) | 70.6 (44.0–89.7) | 73.7 (56.7–85.7) | 85.7 (61.3–95.8) | 78.8 (61.1–91.0) | 44.4 (13.7–78.8) | 90.9 (58.7–99.8) | 80.0 (34.–96.8) | 66.7 (51.9–78.7) | 70.0 (45.7–88.1) | 72.0 (50.6–87.9) | 78.6 (59.2–91.7) | 47.2 (33.3–61.4) | 75.0 (58.6–86.4) | 75.5 (61.7–86.2) |

AD: atopic dermatitis; APT: atopy patch test; GI: gastrointestinal; NPV: negative predictive value; PPV: positive predictive value; SPT: skin prick test.

In this study, we evaluated the efficacy of APT, SPT and sIgE for the diagnosis of patients with suspected CMA and HEA who had atopic dermatitis and gastrointestinal symptoms. We found a higher level of sensitivity and accuracy for APT in patients with atopic dermatitis compared to those with gastrointestinal symptoms. On the other hand, specificity of APT was higher in patients with gastrointestinal symptoms.

Conflicting results have been reported in previous studies. A study evaluating non-IgE-mediated reactions in patients diagnosed with CMA based on gastrointestinal manifestations showed 77% sensitivity and 73% specificity.12 Another study performed in Italy with the same study group reported sensitivity and specificity as 53.8% and 97.8%, respectively.13 These studies revealed a higher sensitivity, but a lower specificity compared to our findings. We suggest that using 12mm diameter chambers in both studies is the main variable that caused different sensitivity and specificity results. Previous studies have utilized different chambers (Finn chamber vs. IQ chamber) with different diameters (6mm–8mm–12mm).14–17 Niggemann et al. detected that APT with 12mm chambers provided better results compared to 6mm chambers.18

While we detected a sensitivity of 71.4% for APT in atopic dermatitis patients with CMA, a study performed in Thailand found this sensitivity to be 42.9%.19 Similarly, higher specificity of APT in HEA patients with atopic dermatitis was found in the present study compared to that same study (85.7% vs. 40%).19 Furthermore, our results are higher than meta-analysis results that reported the pooled sensitivity and specificity as 53.6% and 88.6%, respectively.7 The main factor creating these conflicting results may be using the open OFC instead of double-blind placebo-controlled OFC which is the gold standard for the diagnosis of food allergies.14,15,19

Another issue resulting in different reports concerning the diagnostic accuracy of APT is the differences in the application method of APT. While some studies used lyophilized or powdered food with different concentrations, fresh foods were used in some studies.15,16,20 Gonzaga et al. found sensitivity of APT prepared with fresh whole cow's milk and powdered skimmed cow's milk in petrolatum as 0%.14 On the other hand, the sensitivity of APT prepared with powdered skimmed cow's milk in saline was determined as 33%.14 Overall, we believe that well-defined and standardized methods should be determined for APT before the evaluation of diagnostic efficacy of APT.

In the evaluation of patients presenting with atopic dermatitis, we found higher sensitivity and specificity rates of APT compared to those with gastrointestinal symptoms. The mechanism of APT with suspected allergens in atopic dermatitis is based on the pathophysiological mechanism of atopic dermatitis in which immediate IgE-mediated mechanisms concurrently exist with T-cell-induced delayed hypersensitivity which is characterized by inflammatory dendritic epidermal cells and a Th2 helper cytokine pattern in the first 24h of the test with a shift to a Th1 helper pattern after 48h.15,9 However, non-IgE mediated gastrointestinal system symptoms, for instance constipation, most likely occurred by local allergic inflammation of the internal sphincter area due to mucosal infiltration of mast cells and eosinophils.21,22 Moreover, increasing intestinal IFN-g level, imbalance between intestinal TNF-a levels and decreased expression of TGF-b in FPIES suggests that a local effect of the suspected allergen causes gastrointestinal symptoms.23,24 All these anecdotes may explain the reason for the higher diagnosis accuracy of APT in patients with atopic dermatitis than patients with gastrointestinal manifestation in our study.

Combination of diagnostic tests to achieve better diagnostic accuracy in food allergy has been tested in several previous studies.15,25,26 Canani et al. reported that the combination of APT and SPT improved the overall predictive power.25 However, another study that included children diagnosed with CMA and HEA in addition to atopic dermatitis suggested that the combination of tests did not improve the predictive value of APT.26 A recent study found no improvement in the diagnostic value with combined SPT and APT.15 In our study, we found a limited positive effect of the combination of tests in CMA patients diagnosed with atopic dermatitis. In CMA patients who had gastrointestinal symptoms and patients with HEA, no improvement was noted with the combination of SPT and APT. Determination of negative SPT in all patients presenting with gastrointestinal manifestation may be the reason for this finding.

This study has several limitations. Firstly, we performed open OFC for all patients instead of double-blind placebo-controlled OFC. Secondly, the small sample sizes of the subgroups limited the interpretation of efficacy of these tests. Thirdly, we used only fresh food for APT, and did not assess the patients with commercial extracts with different concentrations. It is well-known that the application methods of APT affect the diagnostic accuracy of APT.

In conclusion, our study showed that APT had reliable diagnostic accuracy in patients with atopic dermatitis. However, APT had low sensitivity in patients with gastrointestinal symptoms. Efficacy of APT varied according to clinical symptoms of the patients. Overall, neither APT nor the combination of APT and SPT proved to be satisfactory methods in the diagnosis of CMA and HEA compared to OFC. Multi-centre prospective studies with standardized APT are warranted to better define the efficacy of these tests.

FundingThis research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflict of interest to declare.