Related to exercise hypothesis, the aim of the present study was to explore the influence of physical activity on asthma and allergic rhinitis in a developing country where publicity campaigns about the benefits of exercise are scarce.

MethodsThe analysed data were self-reported and obtained through the standardized International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood Phase Three written questionnaires completed by 3026 adolescents 13/14 year old in Skopje (Republic of Macedonia). Vigorous physical activity and television-watching time—both unadjusted and adjusted for confounding factors—were used as variables for analysis. Odds ratios (OR, 95 % CI) in binary logistic regression were employed for statistic analysis of the data.

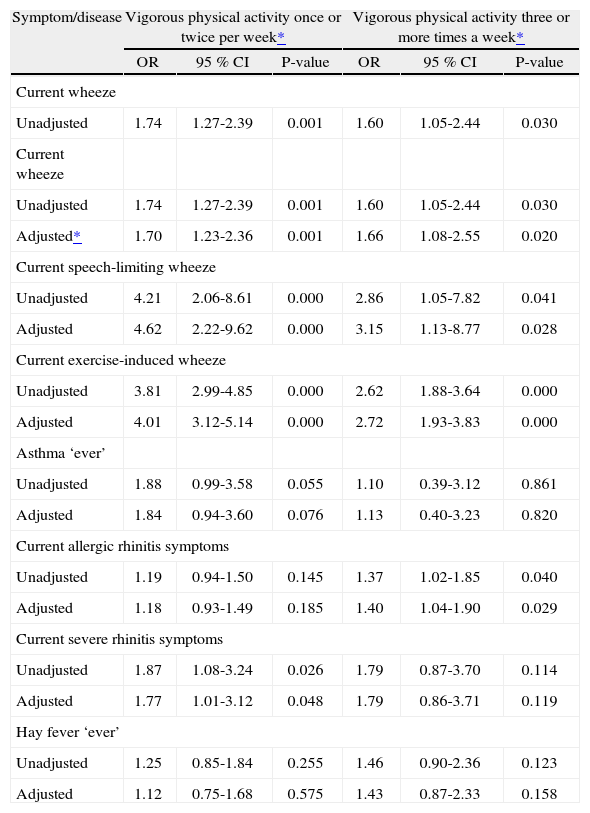

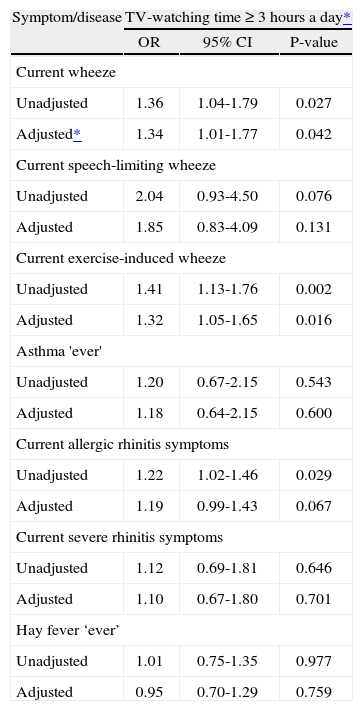

ResultsVigorous physical activity both ≥ 3 times and 1-2 times per week was associated with an increased risk of current wheeze (aOR: 1.66; 1.08-2.55; p = 0.020 and aOR: 1.70; 1.23-2.36; p = 0.001, respectively), speech-limiting wheeze (aOR: 3.15; 1.13-8.77; p = 0.028 and aOR: 4.62; 2.22-9.62; p = 0.000, respectively) and exercise-induced wheeze (aOR: 2.72; 1.93-3.83; p = 0.000 and aOR: 4.01; 3.12-5.14; p = 0.000, respectively). Frequent physical activity was positively associated only with current allergic rhinitis symptoms (aOR: 1.40; 1.04-1.90; p = 0.029). Television watching ≥ 3 hours a day increased the risk of current wheeze (aOR: 1.34; 1.01-1.77; p = 0.042) and exercise-induced wheeze (aOR: 1.32; 1.05-1.65; p = 0.016).

ConclusionThe findings support the aggravating role of sedentary regimen and poor physical fitness on asthma symptoms, but not on allergic rhinitis. Physical activity may trigger asthma symptoms when physical fitness is poor and asthma is not controlled.

An increase in the prevalence of asthma and allergic rhinitis in children and adolescents has been accounted in most countries worldwide1. On the other hand, modern lifestyle had led to an increased inactivity among the population2 previous to the onset of publicity campaigns about the benefits of exercise.

Exercise hypothesis suggests a preventive role of regular exercise and physical fitness on asthma. The underlying mechanisms of this effect, although not well understood as yet, may be the induction of larger respiratory manoeuvres with larger ventilatory capacities and the relaxing effect on smooth airway muscles3,4, the induction of a higher ventilatory threshold and thus a lower ventilatory stimulus to asthma, the higher threshold to respiratory symptoms induced by alterations in the brain's ventilatory chemosensitivity, the lower risk for obesity3,5 and the suppression of the release or activity of inflammatory mediators involved in the pathogenesis or severity of asthma2.

Conversely, about 75–80 % of asthmatic subjects out of therapy may experience asthma symptoms when they exercise, but in recent years, even in apparently healthy subjects, episodes of exercise-induced asthma have been reported. Vascular and osmolar hypotheses are proposed as an explanation6.

Allergic rhinitis is closely pathophysiologically linked with asthma and is frequently accompanied by asthma. Even though some athletes experience improvement in rhinitis when exercising, probably through an increase in the nasal sympathetic tone, their rhinitis may also worsen through greater exposure to allergens and irritants during exercise7.

Several studies have indicated an inverse association between physical activity and asthma3,8–10, some studies a positive association11,12 and there are studies which have reported no association between them at all13,14. In contrast to asthma, the influence of physical activity on allergic rhinitis has been less extensively studied to date and it has been found to be inverse10,15, probably through reduction of the amount of inflammation mediators during moderate physical activity15.

The aim of the present study was to assess the impact of both physical activity and television-watching time on asthma and allergic rhinitis among young adolescents in the Republic of Macedonia, as a developing country with moderately low prevalence rates of these allergic diseases which are under-diagnosed and under-treated and where publicity campaigns about the health benefits of exercise are scarce.

SUBJECTS AND METHODSAs part of the Macedonian arm of the third phase of the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC), the present study was conducted in accordance with its protocol16,17, in Skopje, the capital of the Republic of Macedonia.

The analysis was based on self-reported data obtained through the ISAAC Phase Three written core questionnaires on asthma and allergic rhinitis, as well as through the environmental questionnaire completed, after obtaining informed consent from parents, by 3026 young adolescents aged 13/14years from 17 randomly selected schools. The data collection was conducted under the supervision of the research team out of the main pollen season16, in the period from December 2001 to March 2002. A responserate of 90.9 % was achieved.

Outcome measures used in the study regarding asthma were the 12-month prevalence rates of asthma symptoms (current wheeze, current speech-limiting wheeze, current exercise-induced wheeze) and the prevalence of lifetime diagnosis of asthma (asthma ‘ever’). They were obtained from core questions about the presence of wheezing or whistling in the chest in the last 12months, speech limitation due to wheeze in the last 12months, wheezing during or after exercise in the last 12months and ever having had doctor-diagnosed asthma, respectively. Regarding allergic rhinitis, outcome measures were the 12-month prevalence rates of allergic rhinitis symptoms (current allergic rhinitis symptoms, current severe rhinitis symptoms) and the prevalence of lifetime diagnosis of hay fever (hay fever ‘ever’), which were attained from questions about sneezing or a runny/blocked nose apart from a cold/flu in the last 12months, interference of rhinitis symptoms with daily activities in the last 12months and ever having had doctor-diagnosed hay fever, respectively. Severity indices related to allergic rhinitis symptoms were subcategorized into ‘none’ and ‘any’16,18,19.

The vigorous physical activity long enough to make breathe hard during a week (never/occasionally, 1–2 times per week, ≥ 3 times a week) and television (TV)-watching time daily during a normal week (< 3 hours and ≥ 3 hours a day) were separately correlated to asthma and allergic rhinitis indices.

The gender, mother's educational level, passive tobacco smoke exposure at home, trucks passage through the residential street on weekdays, cat ownership in the last 12months, body mass index (BMI), as factors which may be associated with adolescent's lifestyle regarding their physical activity, were all used as confounding factors for physical activity and TV-watching adjustment. The mother's educational level, as a familiar socioeconomic status indicator, was classified as tertiary (university) versus secondary or primary educational level. Trucks passage through the residential street, as a parameter for outdoor air pollution, was classified as frequent (almost the whole day or frequently through the day) versus infrequent (seldom or never). Self-reported weight and height or, where unknown, their measured values were used for the calculation of the BMI of each respondent as weight (kg)/height (m)2. The international cut-off points for BMI for overweight by sex between 2 and 18years, defined to pass through a BMI of 25kg/m2 at age 18, were used20.

Out of all respondents, 1568 (51.8 %) were boys and 1458 (48.2 %) were girls. Their mean age was 13.45years (SD 0.50).

Ethical approvalThe Ethics Committee at the Medical Faculty and The Ministry of Education and Science, Skopje, the Republic of Macedonia, approved the conduct of the ISAAC Phase Three in the Republic of Macedonia.

Statistical analysesIn accordance with the ISAAC recommendations21, missing or “any other” responses were part of the denominator for calculation of prevalence figures.

We analysed the relationship between the vigorous physical activity per week and the TV-watching time per day respectively—both unadjusted and adjusted for potential confounding factors—and asthma and allergic rhinitis, by employing the odds ratios with 95 % confidence interval (OR, 95 % CI) in binary logistic regression in SPSS 11.0 for Windows. The missing responses to questions concerning asthma and allergic rhinitis were treated as negative responses, whereas the missing responses to questions concerning environmental factors were treated as missing in the analyses. The vigorous physical activity occasionally/never per week and TV-watching time less than 3 hours a day were separately used as referent categories in statistical analyses.

A resulting p-value of < 0.05 was considered significant

RESULTSThe established prevalence rates of both current wheeze (8.8 %) and current exercise-induced wheeze (14.2 %) were significantly higher compared to the prevalence of reported asthma ‘ever’ (1.7 %). The prevalence of current exercise-induced wheeze was also higher compared to the prevalence of current wheeze (p = 0.000; Chi-square test). Current speech-limiting wheeze was established in 1.2 % of the respondents. Current allergic rhinitis symptoms (23.1 %) were also found to be significantly more often than reported hay fever ‘ever’ (6.7 %) (p = 0.000; Chi-square test), while current allergic rhinitis symptoms which interfere with daily activities were documented in 2.5 % of the respondents.

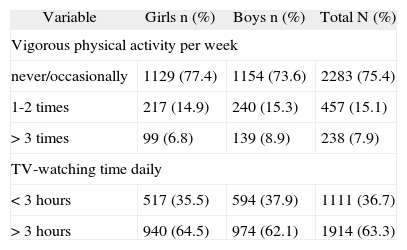

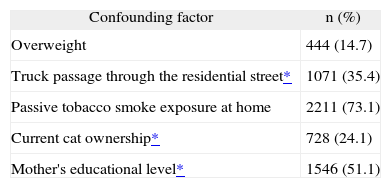

The prevalence rates of vigorous physical activity long enough to make breathe hard during a week and TV-watching time daily during a normal week are shown in Table I. Out of 238 respondents with frequent vigorous physical activity, 146 (61.3 %) watched TV ≥ 3 hours a day and 92 (38.7 %) < 3 hours a day. The prevalence rates of potential confounding factors are given in Table II, while the relationship between vigorous physical activity and asthma and allergic rhinitis in Table III. Current wheeze, speech-limiting wheeze and exercise-induced wheeze were all positively associated with vigorous physical activity 1–2 times per week and ≥ 3 times a week and the significance remained present after controlling for potential confounding factors (for physical activity 1–2 times per week p = 0.001, p = 0.000 and p = 0.000, respectively; for physical activity ≥ 3 times a week p = 0.020, p = 0.028 and p = 0.000, respectively). The significance was higher for infrequent compared to frequent physical activity. Only in the case of positive association between physical activity 1–2 times per week and asthma ‘ever’ the significance was borderline before and after adjustment (p = 0.055 and p = 0.076, respectively). Current allergic rhinitis symptoms were positively associated only with frequent vigorous physical activity and the significance remained present after controlling for confounders (p = 0.029), while current severe rhinitis symptoms were positively associated only with infrequent vigorous physical activity and the significance became borderline after adjustment (p = 0.026 and p = 0.048, respectively).

Prevalence of vigorous physical activity and TV-watching time (written questionnaire) in 3026 adolescents aged 13–14yrs in Skopje, Republic of Macedonia, 2002

| Variable | Girls n (%) | Boys n (%) | Total N (%) |

| Vigorous physical activity per week | |||

| never/occasionally | 1129 (77.4) | 1154 (73.6) | 2283 (75.4) |

| 1-2 times | 217 (14.9) | 240 (15.3) | 457 (15.1) |

| > 3 times | 99 (6.8) | 139 (8.9) | 238 (7.9) |

| TV-watching time daily | |||

| < 3 hours | 517 (35.5) | 594 (37.9) | 1111 (36.7) |

| > 3 hours | 940 (64.5) | 974 (62.1) | 1914 (63.3) |

Prevalence of potential confounding factors (written questionnaire) in 3026 adolescents aged 13–14yrs in Skopje, Republic of Macedonia, 2002

Relationship between vigorous physical activity and asthma and allergic rhinitis in 3026 adolescents aged 13–14yrs in Skopje

| Symptom/disease | Vigorous physical activity once or twice per week* | Vigorous physical activity three or more times a week* | ||||

| OR | 95 % CI | P-value | OR | 95 % CI | P-value | |

| Current wheeze | ||||||

| Unadjusted | 1.74 | 1.27-2.39 | 0.001 | 1.60 | 1.05-2.44 | 0.030 |

| Current wheeze | ||||||

| Unadjusted | 1.74 | 1.27-2.39 | 0.001 | 1.60 | 1.05-2.44 | 0.030 |

| Adjusted* | 1.70 | 1.23-2.36 | 0.001 | 1.66 | 1.08-2.55 | 0.020 |

| Current speech-limiting wheeze | ||||||

| Unadjusted | 4.21 | 2.06-8.61 | 0.000 | 2.86 | 1.05-7.82 | 0.041 |

| Adjusted | 4.62 | 2.22-9.62 | 0.000 | 3.15 | 1.13-8.77 | 0.028 |

| Current exercise-induced wheeze | ||||||

| Unadjusted | 3.81 | 2.99-4.85 | 0.000 | 2.62 | 1.88-3.64 | 0.000 |

| Adjusted | 4.01 | 3.12-5.14 | 0.000 | 2.72 | 1.93-3.83 | 0.000 |

| Asthma ‘ever’ | ||||||

| Unadjusted | 1.88 | 0.99-3.58 | 0.055 | 1.10 | 0.39-3.12 | 0.861 |

| Adjusted | 1.84 | 0.94-3.60 | 0.076 | 1.13 | 0.40-3.23 | 0.820 |

| Current allergic rhinitis symptoms | ||||||

| Unadjusted | 1.19 | 0.94-1.50 | 0.145 | 1.37 | 1.02-1.85 | 0.040 |

| Adjusted | 1.18 | 0.93-1.49 | 0.185 | 1.40 | 1.04-1.90 | 0.029 |

| Current severe rhinitis symptoms | ||||||

| Unadjusted | 1.87 | 1.08-3.24 | 0.026 | 1.79 | 0.87-3.70 | 0.114 |

| Adjusted | 1.77 | 1.01-3.12 | 0.048 | 1.79 | 0.86-3.71 | 0.119 |

| Hay fever ‘ever’ | ||||||

| Unadjusted | 1.25 | 0.85-1.84 | 0.255 | 1.46 | 0.90-2.36 | 0.123 |

| Adjusted | 1.12 | 0.75-1.68 | 0.575 | 1.43 | 0.87-2.33 | 0.158 |

OR: Odds ratio; CI: confidence interval; Current: in the last 12months.

** Adjusted vigorous physical activity for sex, body mass index, truck passage through the residential street, passive tobacco smoke exposure at home, current cat ownership and mother's educational level.

TV-watching ≥ 3 hours a day was positively associated with current wheeze and exercise-induced wheeze both unadjusted and adjusted for confounders (p = 0.042 and p = 0.016, respectively), while the significant positive association with current allergic rhinitis symptoms disappeared after controlling for confounders (p = 0.029 and p = 0.067, respectively) (Table IV).

Relationship between TV-watching time and asthma and allergic rhinitis in 3026 adolescents aged 13–14yrs in Skopje

| Symptom/disease | TV-watching time ≥ 3 hours a day* | ||

| OR | 95% CI | P-value | |

| Current wheeze | |||

| Unadjusted | 1.36 | 1.04-1.79 | 0.027 |

| Adjusted* | 1.34 | 1.01-1.77 | 0.042 |

| Current speech-limiting wheeze | |||

| Unadjusted | 2.04 | 0.93-4.50 | 0.076 |

| Adjusted | 1.85 | 0.83-4.09 | 0.131 |

| Current exercise-induced wheeze | |||

| Unadjusted | 1.41 | 1.13-1.76 | 0.002 |

| Adjusted | 1.32 | 1.05-1.65 | 0.016 |

| Asthma 'ever' | |||

| Unadjusted | 1.20 | 0.67-2.15 | 0.543 |

| Adjusted | 1.18 | 0.64-2.15 | 0.600 |

| Current allergic rhinitis symptoms | |||

| Unadjusted | 1.22 | 1.02-1.46 | 0.029 |

| Adjusted | 1.19 | 0.99-1.43 | 0.067 |

| Current severe rhinitis symptoms | |||

| Unadjusted | 1.12 | 0.69-1.81 | 0.646 |

| Adjusted | 1.10 | 0.67-1.80 | 0.701 |

| Hay fever ‘ever’ | |||

| Unadjusted | 1.01 | 0.75-1.35 | 0.977 |

| Adjusted | 0.95 | 0.70-1.29 | 0.759 |

OR: Odds ratio; CI: confidence interval; Current: in the last 12months.

** Adjusted TV-watching time for sex, body mass index, truck passage through the residential street, passive tobacco smoke exposure at home, current cat ownership and mother's educational level.

Compared to the prevalence rates of asthma worldwide, the Republic of Macedonia appears to have a low prevalence of self-reported ever-diagnosed asthma18. The much higher prevalence rates of current wheeze and exercise-induced wheeze in contrast to the prevalence of reported physician-diagnosed asthma ‘ever’ in young adolescents point to under-diagnosis and consequently to under-treatment of asthma in this age group in our country. The higher prevalence of current exercise-induced wheeze compared to the prevalence of current wheeze may be due to severity and better perception of exercise-induced wheeze in under-diagnosed and under-treated asthma or to different interpretation of wheezing questions or to over-reporting of exercise-induced wheeze by the respondents because of poor physical fitness. The similar differences between the prevalence rates of current exercise-induced wheeze and current wheeze in the same age group in ISAAC written as well in video questionnaires can be noted in many other countries worldwide18.

The Republic of Macedonia is characterised by a relatively safe environment and sufficient number of closely located playgrounds, but TV-watching and computer games are very popular among young adolescents, which can explain the low prevalence of frequent physical activity in the respondents. 61.3% of the respondents who practiced vigorous physical activity ≥ 3 times weekly also watched TV ≥ 3 hours a day, probably engaging in physical activities inside school hours and practicing weekend recreation. Moreover, our physicians and general population still retain a relatively low perception of the beneficial effects of physical activity on health, especially among asthmatics.

In the present study, an increased risk of current wheeze, speech-limiting wheeze and exercise-induced wheeze by vigorous physical activity, infrequent as well as frequent, was determined in comparison with physical inactivity. However, the positive association was stronger between infrequent physical activity and asthma symptoms, than between frequent physical activity and asthma symptoms. On the other hand, TV-watching time increased the risk of current wheeze and exercise-induced wheeze. Although the results seem contradictory, they both may support the aggravating effect of sedentary regimen and poor physical fitness on asthma symptoms.

It seems that vigorous physical activity might trigger asthma symptoms in our respondents because of their sedentary regimen and poor physical fitness, as well as due to asthma being under-diagnosed and consequently under-treated. Sedentary lifestyle decreases physical fitness and increases ventilation during exercise thereby rising the likelihood of provoking exercise-induced asthma symptoms5. The higher degree of bronchial hyper-responsiveness in uncontrolled asthma could impose limitations on exercise tolerance22,23. Intense physical activity in children and adolescents may either trigger asthma symptoms, or may improve physical fitness and protect against asthma3. The increased risk of asthma symptoms in our respondents by TV watching, as a proxy of physical inactivity24, is in consent with the exercise hypothesis with its proposed underlying mechanisms2–5. So, the overall findings in the present study support the exercise hypothesis in asthma i.e. the inverse association between regular exercise and physical fitness and asthma symptoms.

Our results are consistent with previous research demonstrating the aggravating role of sedentary regimen and poor physical fitness on asthma. An association between decreased levels of physical activity, measured with a motion sensor, and a history of current wheeze, diagnosis of asthma and emergency room visits because of current wheeze or asthma in inner-city children has been reported2. Tsai et al25, through TV-watching time and frequency of physical exercise, have documented an aggravating role of sedentary lifestyle on asthma and respiratory symptoms in schoolchildren. It was established by Rasmussen et al3 that physical fitness among schoolchildren aged 8years or older was inversely related to the subsequent development of physician-diagnosed asthma. Moreover, an inverse association between bronchial responsiveness and hours of exercise per week in asthmatic children and young adolescents8 as well in adults from the general population4 has also been demonstrated.

However, Lang et al26 have found that the parental health beliefs regarding exercise and disease severity contributed to a lower activity level in asthmatic inner-city children. Unpleasant symptoms resulting from exercise-induced bronchoconstriction may also incline the asthmatic child to avoid physical activity22. Furthermore, Vogelberg et al24, in a questionnaire-based study conducted among adolescents, have reported an inverse relationship between physical activity and new onset of wheeze, which was not an independent effect but mediated by differences in active smoking.

In contrast to the studies which have documented an inverse association of physical activity with asthma, other studies have found a positive association. Ownby et al12 have found that higher levels of physical activity, measured in metabolic equivalents, were related to more frequently diagnosed asthma in children. A positive association between vigorous physical activity and wheezing and whistling in the chest in the last 12months in asthmatic and non-asthmatic children was also reported by Nystad et al11. It is known that physical training may provoke exerciseinduced bronchoconstriction in asthmatic patients23 and that it may affect sensation and report of asthma symptoms3,11 which might be the possible explanations of the aforementioned findings.

Accordingly, the association between physical activity and asthma is not necessarily causative and is still uncertain. Regardless of the cause and effect, physical activity is an important contributor to physical fitness in children with or without asthma and should not be avoided.

Regarding allergic rhinitis, in the present study, a positive association was established only between frequent vigorous physical activity and current allergic rhinitis symptoms, which is in contrast to the studies published recently by Garcia-Marcos et al10 and Kohlhammer et al15. In the first study10, exercise has been found to be a protective factor for rhinoconjunctivitis and current occasional asthma in children aged 6–7years in both sexes. In the second study15, significantly higher rates of hay fever were found in inactive children without any association between physical inactivity and allergic sensitisation. As neither vigorous physical activity nor TV-watching time were associated with ever-diagnosed hay fever and its severity, the established positive association between frequent physical activity and current allergic rhinitis symptoms in the present study may be due to chance or to a greater exposure to allergens or irritants7.

The present study has several potential limitations. As with other questionnaire-based studies, there is a possibility of information bias. However, administratin of self-reported physical activity questionnaires is considered to be the only practical method of collecting a broad range of data from a large sample of children and adolescents. We employed as a determinant of physical fitness only the self-reported frequency of regular vigorous physical activity. On account of the almost equal gender distribution and prevalence of vigorous physical activity and TV-watching time, the analyses were conducted on the whole group of respondents. Gender was, however, included in the analyses as a controlling factor. Finally, because of the cross-sectional design of the study, a cause-and-effect relationship between physical activity and asthma and allergic rhinitis cannot be determined.

In conclusion, the self-reported data from young adolescents in the Republic of Macedonia, a country with moderately low prevalence rates of asthma and allergic rhinitis – which are at any rate under-diagnosed and under-treated – and a low prevalence of physical activity, seem to support the aggravating role of sedentary regimen and poor physical fitness on asthma symptoms, but not on allergic rhinitis. Physical activity may trigger asthma symptoms when asthma is under-diagnosed and not controlled, and physical fitness is poor. Although the cause-andeffect relationship between physical activity and asthma is still not well defined, steps should be taken to improve asthma diagnosis and treatment and to encourage physical activity to improve physical fitness in early adolescence.

The authors would like to thank young adolescents for their participation in the survey and the principals, psychologists and teachers from the selected schools for their collaboration. The Ministry of Education and Science of The Republic of Macedonia provided financial support for the study.