The term “mastocytosis” denotes a heterogeneous group of disorders characterised by abnormal growth and accumulation of mast cells (MC) in one or more organ systems. Symptoms result from MC chemical mediator's release, pathologic infiltration of neoplastic MC in tissues or both. Multiple molecular, genetic and chromosomal defects seem to contribute to an autonomous growth, but somatic c-kit D816V mutation is more frequently encountered, especially in systemic disease.

We present a literature review of mastocytosis and a rare case report of an 18 month-old-girl with a bullous dermatosis, respiratory distress and anaphylaxis, as clinical manifestations of mastocytosis.

The developments of accepted classification systems and novel useful markers allowed a re-evaluation and updating of the classification of mastocytosis. In paediatric age cutaneous forms of disease prevail and may regress spontaneously. SM is more frequently diagnosed in adults and is a persistent (clonal) disease of bone marrow. The clinical course in these patients is variable.

Today diagnostic criteria for each disease variant are reasonably well defined. There are, however, peculiarities, namely in paediatric age, that makes the diagnostic approach difficult. Systemic disease may pose differential diagnostic problems resulting from multiple organ systems involvement. Coversly, the “unexplained” appearance of those symptoms with no skin lesions should raise the suspicion of MC disease.

This case is reported in order to stress the clinical severity and difficult diagnostic approach that paediatric mastocytosis may assume.

In 1869, Nettleship and Tay first described the typical mastocytosis lesions (urticaria pigmentosa) as a rare form of urticaria.1 Soon after the discovery of mast cells (MC), by Paul Ehrlich in 1879, these lesions were found to contain focal accumulations of MC.2 However, it was not until 1949 that Ellis described the systemic variant of the disease with involvement of visceral organs.3

DEFINITIONThe term “mastocytosis” denotes a heterogeneous group of disorders characterised by abnormal growth and accumulation of MC in one or more organ systems. It is also described as a neoplastic disease involving MC and their progenitors CD34+.4

EPIDEMIOLOGYCurrent estimates on prevalence of mastocytosis range from 1 in 1000 to 8000 patients in the dermatology office.5 In children approximately 5.4 cases per 1000 children are treated in dermatological clinics.6 Rosbotham et al estimated that there are two new cases per year in a population of 300,000 corresponding to an incidence of 0.000667 %.7

Mastocytosis occurs equally in both sexes and as been described in different ethnic groups, although there are more reports in caucasians.8

PATHOPHYSIOLOGYMC are haematopoietic cells that reside in vascularized tissues, namely the connective tissues, often in the vicinity of smaller or larger blood vessels or nerve fibres.9,10 They are derived from multipotent hematopoietic progenitors CD34+, detectable in bone marrow as well as peripheral blood. Subsequently they distribute in the blood and transmigrate through the endothelial barrier into tissues before undergoing terminal differentiation and maturation.11,12 During differentiation MC acquire distinct morphologic and phenotypic properties with four defined stages of maturation: the non-granulated (tryptasepositive) blast cell; the metachromatic blast cell; the promastocyte/atypical MC type II and the mature MC.13 Several cytokines and the local microenvironment are considered to contribute to mastopoiesis. A pivotal cytokine in this process, the principle MC growth factor, is the Stem Cell (SCF) or kit-ligand.14–18 The effects of SCF on MC and their progenitors are mediated through a specific MC's receptor – transmembrane tyrosine kinase receptor, KIT or CD117.12 This is in turn encoded by the c-kit proto-oncogene.12,19 Therefore, a “gain-of-function mutations” in the c-kit gene might be associated to enhanced growth and resistance to apoptosis of MC and their progenitors.20 Several c-kit mutations have been identified.10 The point mutation D816V (Asp-816-Val) is the most frequently detected (> 80 % of all patients with SM).21–24 Apparently additional defects are needed (molecular, genetic and chromosomal) in order for an autonomous cellular growth to occur.25–27 In contrast to sporadic cases, patients with familial Mastocytosis usually fail to express c-kit mutations,22 associated with resistance to imatinib.28 Yet, a novel c-kit mutation has been identified in familial responsive to imatinib therapy.27 The heterogeneity of c-kit mutations, and consequent clinical heterogeneity (age of onset of disease, patterns of skin disease, degree of organic involvement, hematopathology, mediator levels, response to therapy and prognosis), makes genotype-phenotype correlations characterization difficult.29,30 At least four ways have been suggested: single mutation at codon 816; sequential mutations (mutation at codon 816 allows further mutations); simultaneous mutations (others than 816 mutation) and chromosomal instability (predisposing to mutation at codon 816 and others).29

Another important pathogenic aspect (in SM) is the abnormal expression of cell surface adhesion antigens CD2 (LFA-2) and CD25, identified by multicoloured flow cytometry.31,32 The most immature MC progenitors (both normal and neoplastic) express CD13, CD34 and CD117.

MC are easily recognisable by their metachromatic intracytoplasmatic granules where vasoactive and immunoregulatory mediators including histamine, heparin and cytokines are stored. Several are released in response to aggregation of the high affinity IgE receptor, activation through complement receptors or activation by cytokines.12 Others, such as tryptase, are both constitutively secreted from MC and released after its activation. Two tryptase genes (α and β) are expressed by human MC. α-(pro) tryptase is secreted constantly from the cell and its levels reflect the total tryptase baseline, which appear to correlate with the MC number.33 β-tryptase is stored in MC granules and levels are found to be elevated after MC activation, such as anaphylaxis, and are usually otherwise undetectable. Total serum tryptase levels are a reliable non-invasive diagnostic approach to estimate the burden of MC in patients with mastocytosis and allow the distinction between categories of disease.34 In healthy individuals an average 5ng/ml is found (< 15 ng/ml).33

Symptoms in mastocytosis result from MC-derived mediators and, less frequently, from destructive infiltration of MC [skin, bone marrow, gastrointestinal tract, skeletal, central nervous system (CNS) or lymphoreticular system (spleen, liver and lymph nodes)].37

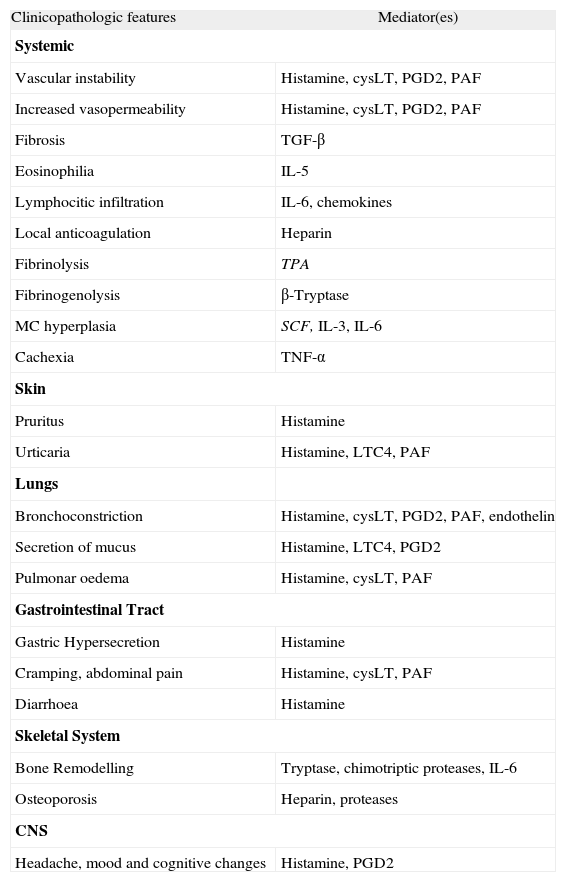

The MC produce and release a variety of clinically relevant mediators such as histamine, leukotrienes, proteases or heparin (table I). Depending on the type of MC involved, burden of MC, course of disease and co-existing disorders, these mediators may be released to a variable degree resulting in different clinical patterns.38–40 In some of these patients the symptoms are mild and may not require therapy, in others, they are severe and potentially fatal (urticaria, recurrent flushing, dyspnoea, chest pain, bleeding tendency, peptic ulcer, abdominal pain, severe bone pain, headache, recurrent syncope and hypotensive shock).38–40

Clinicopathologic features of mastocytosis associated MC mediators

| Clinicopathologic features | Mediator(es) |

| Systemic | |

| Vascular instability | Histamine, cysLT, PGD2, PAF |

| Increased vasopermeability | Histamine, cysLT, PGD2, PAF |

| Fibrosis | TGF-β |

| Eosinophilia | IL-5 |

| Lymphocitic infiltration | IL-6, chemokines |

| Local anticoagulation | Heparin |

| Fibrinolysis | TPA |

| Fibrinogenolysis | β-Tryptase |

| MC hyperplasia | SCF, IL-3, IL-6 |

| Cachexia | TNF-α |

| Skin | |

| Pruritus | Histamine |

| Urticaria | Histamine, LTC4, PAF |

| Lungs | |

| Bronchoconstriction | Histamine, cysLT, PGD2, PAF, endothelin |

| Secretion of mucus | Histamine, LTC4, PGD2 |

| Pulmonar oedema | Histamine, cysLT, PAF |

| Gastrointestinal Tract | |

| Gastric Hypersecretion | Histamine |

| Cramping, abdominal pain | Histamine, cysLT, PAF |

| Diarrhoea | Histamine |

| Skeletal System | |

| Bone Remodelling | Tryptase, chimotriptic proteases, IL-6 |

| Osteoporosis | Heparin, proteases |

| CNS | |

| Headache, mood and cognitive changes | Histamine, PGD2 |

LT, leukotrienes; PG, prostaglandins; PAF, Platelet Activating Factor; TGF, Transforming Growth Factor; IL, interleukin; SCF, Stem Cell Factor; TNF, Tumor Necrosis Factor; TPA, Tissue Type Plasminogen Activator; CNS, Central Nervous System.

Adapted from Valent et al.5

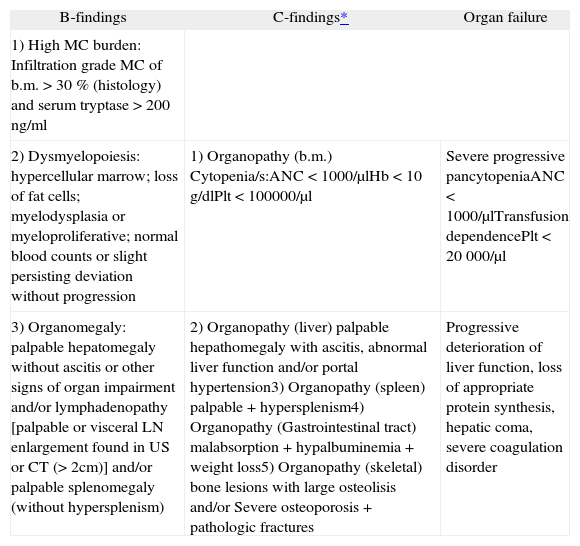

Organ infiltration may occur: without organ dysfunction (B-findings); with impaired organ function (C-findings) or organ failure (table II).

B and C findings

| B-findings | C-findings* | Organ failure |

| 1) High MC burden: Infiltration grade MC of b.m. > 30 % (histology) and serum tryptase > 200 ng/ml | ||

| 2) Dysmyelopoiesis: hypercellular marrow; loss of fat cells; myelodysplasia or myeloproliferative; normal blood counts or slight persisting deviation without progression | 1) Organopathy (b.m.) Cytopenia/s:ANC < 1000/μlHb < 10 g/dlPlt < 100000/μl | Severe progressive pancytopeniaANC < 1000/μlTransfusion dependencePlt < 20 000/μl |

| 3) Organomegaly: palpable hepatomegaly without ascitis or other signs of organ impairment and/or lymphadenopathy [palpable or visceral LN enlargement found in US or CT (> 2cm)] and/or palpable splenomegaly (without hypersplenism) | 2) Organopathy (liver) palpable hepathomegaly with ascitis, abnormal liver function and/or portal hypertension3) Organopathy (spleen) palpable + hypersplenism4) Organopathy (Gastrointestinal tract) malabsorption + hypalbuminemia + weight loss5) Organopathy (skeletal) bone lesions with large osteolisis and/or Severe osteoporosis + pathologic fractures | Progressive deterioration of liver function, loss of appropriate protein synthesis, hepatic coma, severe coagulation disorder |

b.m: bone marrow; ANC: absolute neutrophile count; Plt: platelets; LN: lymph node; US: ultrasound; CT: computer tomography.

Adapted from Valent et al.5

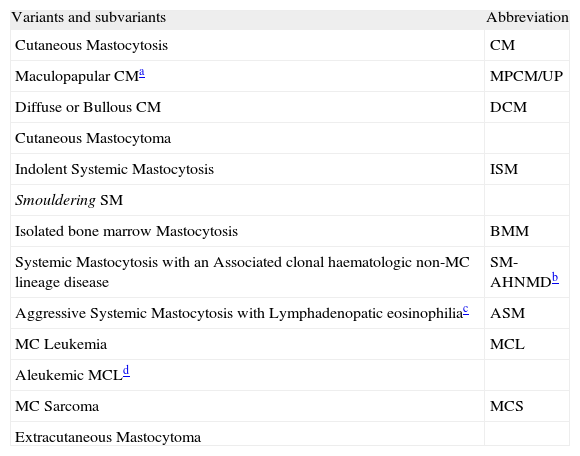

On the basis of recent advances in mastocytosis research, an updated consensus classification for mastocytosis was proposed in 2001 and subsequently adopted by the WHO (table III).41

WHO classification of Mastocytosis

| Variants and subvariants | Abbreviation |

| Cutaneous Mastocytosis | CM |

| Maculopapular CMa | MPCM/UP |

| Diffuse or Bullous CM | DCM |

| Cutaneous Mastocytoma | |

| Indolent Systemic Mastocytosis | ISM |

| Smouldering SM | |

| Isolated bone marrow Mastocytosis | BMM |

| Systemic Mastocytosis with an Associated clonal haematologic non-MC lineage disease | SM-AHNMDb |

| Aggressive Systemic Mastocytosis with Lymphadenopatic eosinophiliac | ASM |

| MC Leukemia | MCL |

| Aleukemic MCLd | |

| MC Sarcoma | MCS |

| Extracutaneous Mastocytoma |

Adapted from Valent et al.5

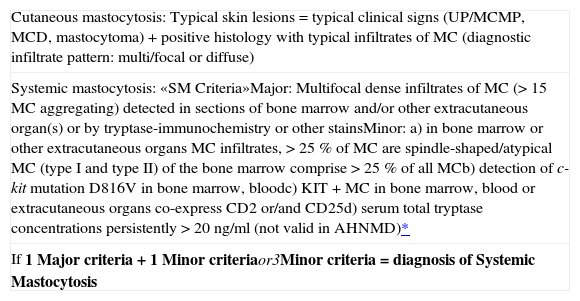

The proposed classification is based on formulated criteria. In this concept cutaneous mastocytosis (CM) is based on clinical (urticaria pigmentosa, Darier's sign, mastocytoma) and histological findings (multi/focal or diffuse infiltrates of MC) together with the absence of criteria that would allow the diagnosis of SM. SM criteria are divided into major criteria (histological and immunohistochemical) and minor criteria (typical cytomorphological and novel biochemical markers) listed in table IV.

Proposed criteria to diagnose mastocytosis

| Cutaneous mastocytosis: Typical skin lesions = typical clinical signs (UP/MCMP, MCD, mastocytoma) + positive histology with typical infiltrates of MC (diagnostic infiltrate pattern: multi/focal or diffuse) |

| Systemic mastocytosis: «SM Criteria»Major: Multifocal dense infiltrates of MC (> 15 MC aggregating) detected in sections of bone marrow and/or other extracutaneous organ(s) or by tryptase-immunochemistry or other stainsMinor: a) in bone marrow or other extracutaneous organs MC infiltrates, > 25 % of MC are spindle-shaped/atypical MC (type I and type II) of the bone marrow comprise > 25 % of all MCb) detection of c-kit mutation D816V in bone marrow, bloodc) KIT+ MC in bone marrow, blood or extracutaneous organs co-express CD2 or/and CD25d) serum total tryptase concentrations persistently > 20 ng/ml (not valid in AHNMD)* |

| If 1 Major criteria + 1 Minor criteriaor3Minor criteria = diagnosis of Systemic Mastocytosis |

Adapted from Valent et al.5

The existence of one major and one minor criterion or three minor criteria establish the diagnosis of SM.41

CLINICAL FEATURESThe occurrence of mastocytosis is usually sporadic. Familial mastocytosis (AD) is a very rare condition with only 50 families recorded in the literature since 1880.22 In up to 15 % of patients the disease is congenital.35

Approximately 65 % of individuals with mastocytosis present with disease in childhood; 55 % of these have manifestations of disease by the age of two. The remaining 35 % that develop the symptoms after puberty are classified as adult onset.36

Most pediatric cases of mastocytosis are asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic with spontaneous resolution during or after adolescence (50 %).42 Around 90 % of these patients have isolated cutaneous symptoms, while 10 % have systemic involvement.43 It is, therefore, a benign condition.44

Urticaria pigmentosa (UP) is the most common variant of CM.45 It usually presents as red-brown macules and papules, often with symmetrical distribution and even anaphylactic reaction after mechanical/thermal stimulation of skin lesions.46 In contrast, dermographism is characterised by the appearance of the same lesions after stroking or scratching normal appearing skin. Three rare subvariants of UP have been proposed based on distinct clinical aspects: plaque form, a nodular form and a telangiectasic (Telangiectasia Macularis Eruptiva Persistans – TMEP). The younger the patient and the smaller the number of the lesions the higher the probability of spontaneous remission. An adult onset of disease raises the risk of systemic involvement and long persistence.10 Bullous mastocytosis or Diffuse CM is a very rare and severe variant of CM which usually occurs in the first year of life.47 It is characterised by intensely itchy, generalised yellowish, thickened skin with doughy/leathery feel and the appearance of large blisters, sometimes haemorrhagic, spontaneously or following mild trauma due to diffuse MC infiltration.45,47 Children with more extensive skin involvement are more likely to exhibit systemic symptoms: flushing, headache, palpitations, abdominal pain, diarrhoea, dyspnoea, wheezing, syncope, hypotensive shock and death.45 Early onset of blisters worsens the prognosis. It is also associated with an increased risk of progression to MCL.48 The mastocytoma of the skin presents as a macular, papular or nodular (< 1cm) lesion of yellow, brown or reddish colour. It rarely evolves into SM-AHNM.49

Patients with adult onset mastocytosis generally have evidence of systemic disease (SM). It can follow a benign/indolent course as a persistent clonal disorder (disorder of the bone marrow) or it may be associated with life-threatening haematologic disorders. SM includes four major subtypes: indolent SM (ISM); SM associated with non-mast cell clonal haematological disease (SM-AHNMD); aggressive SM (ASM); and MC Leukemia (MCL).41 ISM represents 2/3 of all cases of SM and shows a prolonged clinical course (survival time of two decades or more).41 SM-AHNMD combines two completely different histologies: the MC lineage and non-MC lineage (myelodysplastic syndrome, myeloproliferative syndrome, acute myeloid leukemia, Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma). The haematological disease associated is most frequently (80–90 %) of myeloid lineage.41 The type of haematologic disorder associated determines its prognosis. It is, therefore, important to accurately determine the type of SM in these patients.41 ASM is characterised by progressive infiltration of various organs with function impairment (severe cytopenias, malabsorption, bone fractures, peripheral eosinophilia, and hepatopathy) but usually without typical skin lesions.41 The clinical course is variable. MCL is characterized by leukemic infiltration of various organs by immature neoplastic MC. The prognosis is often poor.41 Localised MC proliferations are extremely rare and include both Extracutaneous Mastocytoma and MC Sarcoma.41 Mastocytoma is a benign tumour with uniformal growth, low grade cytology and good prognosis.41 MC Sarcoma is a local destructive tumour, usually with poor prognosis.41

Patients with SM should be followed-up to monitor the development of any signs of disease progression or evolution to AHNMD.

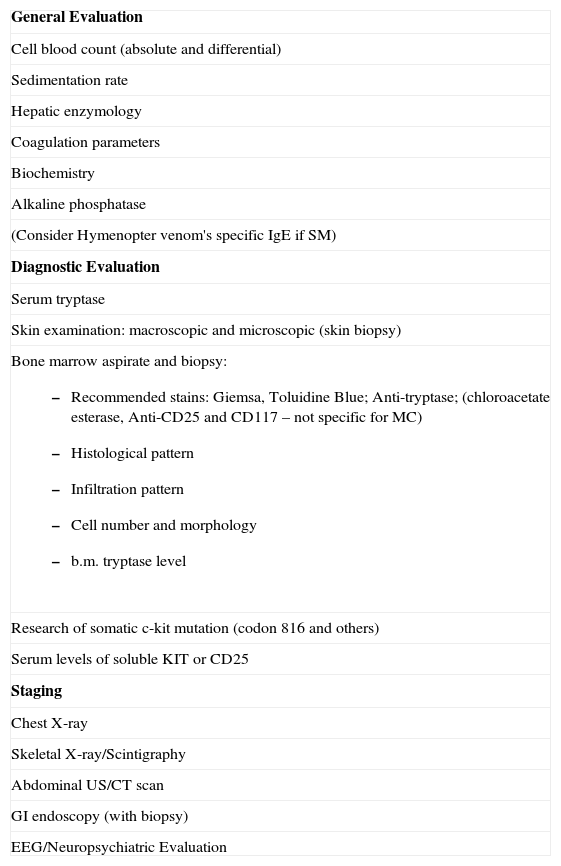

DIAGNOSTIC EVALUATIONCurrent available diagnostic and staging methods are listed in table V.

Diagnostic and Staging methods of Mastocytosis

| General Evaluation |

| Cell blood count (absolute and differential) |

| Sedimentation rate |

| Hepatic enzymology |

| Coagulation parameters |

| Biochemistry |

| Alkaline phosphatase |

| (Consider Hymenopter venom's specific IgE if SM) |

| Diagnostic Evaluation |

| Serum tryptase |

| Skin examination: macroscopic and microscopic (skin biopsy) |

Bone marrow aspirate and biopsy:

|

| Research of somatic c-kit mutation (codon 816 and others) |

| Serum levels of soluble KIT or CD25 |

| Staging |

| Chest X-ray |

| Skeletal X-ray/Scintigraphy |

| Abdominal US/CT scan |

| GI endoscopy (with biopsy) |

| EEG/Neuropsychiatric Evaluation |

Patient's age, clinical findings and laboratory parameters determine the choice of diagnostic and staging methods.

In paediatric patients the disease is usually restricted to the skin and bone marrow examination is not required unless there is late presentation of skin lesions (> 5 years),50 organomegaly, significant peripheral blood abnormalities or persistently elevated serum tryptase levels (> 20 ng/ml).41,51 In early childhood slightly raised serum tryptase levels might be related with a different ratio of MC granule volume/total body volume and total volume of skin MC/total body volume, compared with adults.28

Therefore, consideration should be given to monitoring the serum tryptase level over time and to not perform a bone marrow punction unless there are suggesting signs of systemic disease.

The existence of more then 15 MC per aggregate (diffuse or multifocal infiltrates with a significant percentage of spindle-shape cells) fulfils the diagnosis of SM.52 If the majority of MC are round it is necessary to investigate additional criteria because such accumulations have been detected in reactive MC hyperplasia (parasite infections neoplastic disorders, aplastic anemia, and chronic inflammatory diseases), SCF-treated patients and myeloid leukemia without mastocytosis.41

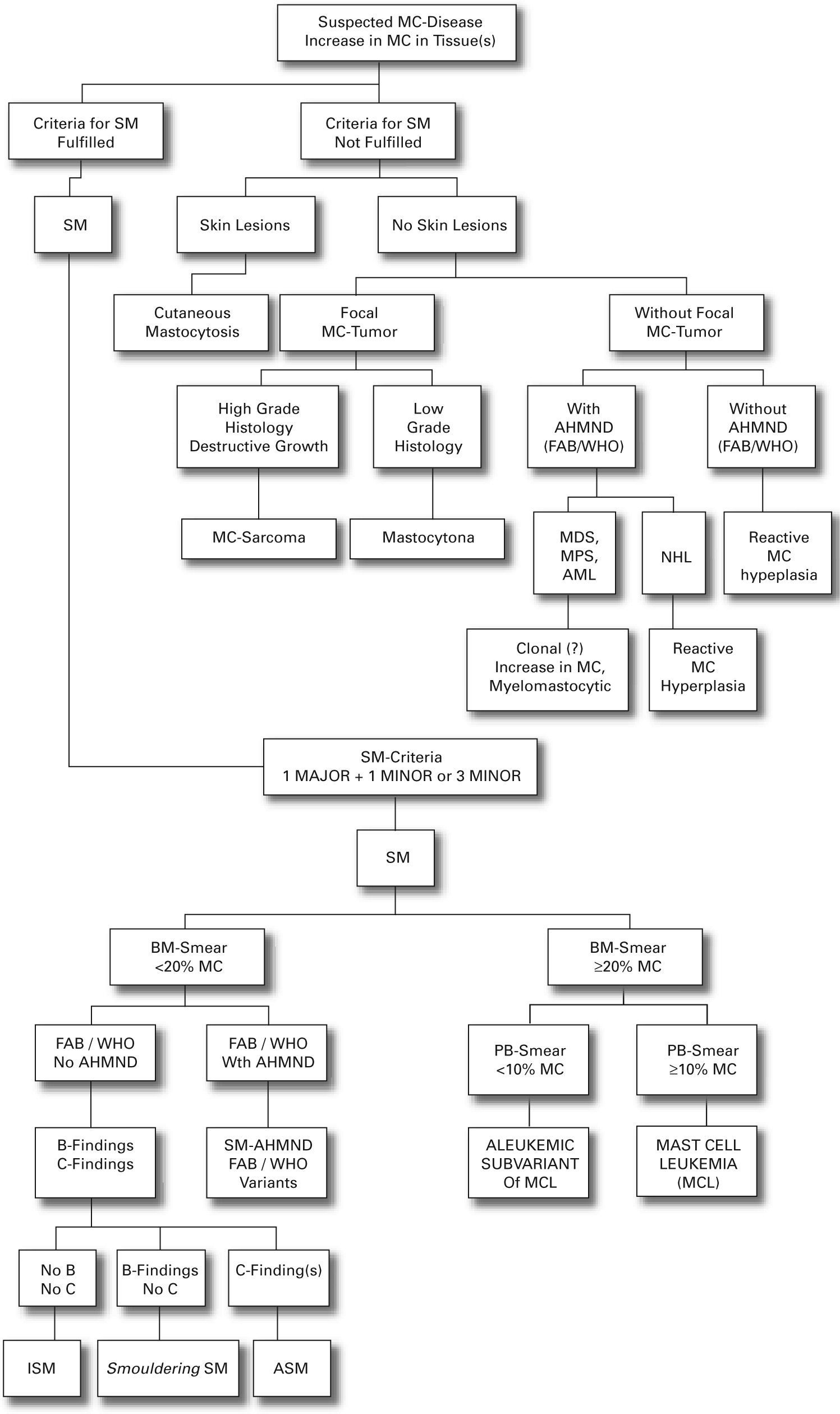

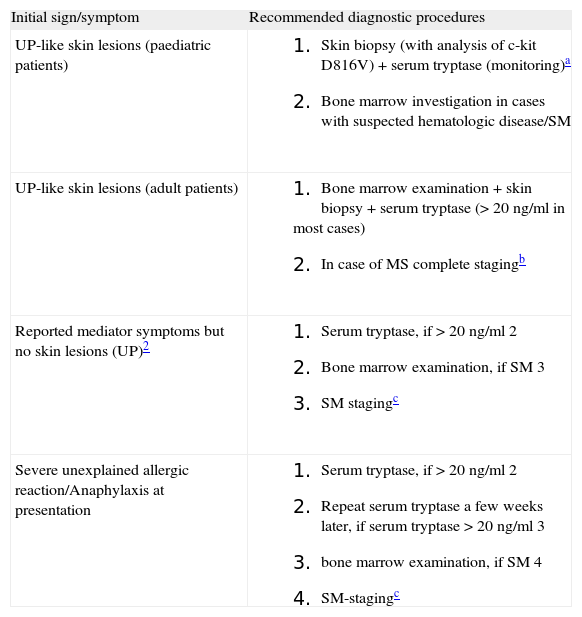

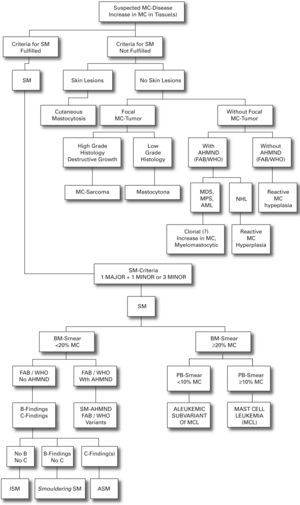

We present a practical guide for diagnostic workup in patients with suspected mastocytosis in table VI. Figure 1 shows a diagnostic algorithm discriminating mastocytosis variants.

Practical guide for diagnostic work-up in patients with suspected mastocytosis

| Initial sign/symptom | Recommended diagnostic procedures |

| UP-like skin lesions (paediatric patients) |

|

| UP-like skin lesions (adult patients) |

|

| Reported mediator symptoms but no skin lesions (UP)2 |

|

| Severe unexplained allergic reaction/Anaphylaxis at presentation |

|

Adapted from Valent et al.6

In young infants, a serum tryptase slightly exceeding 20 ng/ml is not regarded as a safe indicator for SM. Therefore, it is recommended to wait and to monitor the serum tryptase level over time in these patients.

Complete staging: gastrointestinal tract, skeleton (X-ray, scintigraphy), abdomen US, complete blood count, serum chemistry, coagulation, c-kit mutations.

Especially in patients with aggressive MC disorders, skin lesions are absent. Therefore, it is of pivotal importance to know the subtype of SM in these patients as soon as possible. In ASM serum tryptase level is usually higher than in patients with isolated bone marrow mastocytosis (often < 20 ng/ml), a benign MC disease in which skin lesions are also absent.

SM symptoms, in the absence of skin lesions, are often non-specific and thus confused with other underlying conditions namely: endocrine (adrenal tumour, gastrinoma, VIPoma, carcinoid syndrome), cardiovascular (idiopathic anaphylaxis, cardiac disease, aortic stenosis, vasculitis, essential hypertension), gastrointestinal (peptic ulcer, ulcerative colitis, hepatitis, parasite disease, gluten-sensitive enteropathy), pulmonary, allergic, infectious, immunologic, rheumatologic and oncologic.41,10

However, one should be alert to the possibility of MC disease when patients present “inexplicable” symptoms that might be related with MC-mediator release such as vascular instability, anaphylactic shock, flushing, diarrhoea and headache, even if no skin lesions are found.

TREATMENTIt is consensual, since no curative therapies are available, that mastocytosis should be treated according to the symptoms presented.53,54

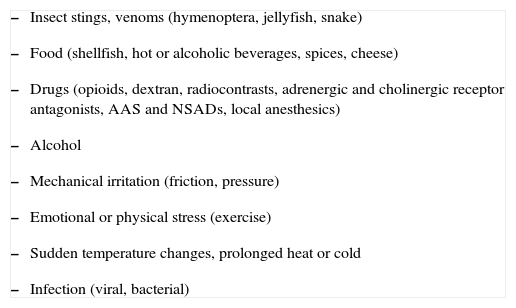

In patients with predominant mediator-release symptoms, “mediator-targeting” drugs must be prescribed in addition to avoidance of triggers of MC degranulation53,54 (table VII).

Triggering factors that induce release of MC mediators in patients with mastocytosis

|

Commonly used medication includes anti-histamines (H1/H2), MC stabilisers, acetylsalicylic acid (aspirin), ketotifen or adrenaline. Aspirin is used for flushing, tachycardia and syncope.55 Ketotifen has been recommended for bone pain and/or flushing.56,57 Gastric ulcerative disease requires the use of H2 anti-histamines or a proton pump inhibitor.56 In many patients a combination of H1 and H2 anti-histamines is administered. Low dose of corticosteroids may relieve malabsorption and ascitis.56 Self administered epinephrine is indicated in recurrent anaphylactic episodes.53,54 Specific immunotherapy for hymenoptera venom might be considered in patients with SM.58 Cutaneous lesions may show good (transient) response to Psoralen-PhotoChemotherapy (PUVA)59 or local corticosteroids.

In case of rapid or aggressive disease progression cytoreductive drugs are recommended: α-interferon, with or without corticosteroids, or cladribine.54,55 If no benefit is achieved one should consider experimental poly-chemotherapy or bone marrow transplant (haematopoietic stem cells).28 Although these modalities can render significant MC reduction and symptom control in some patients, responses are transient and the prognosis remains unchanged.51

In patients with significant splenomegaly and hypersplenism, splenectomy may be considered.60

Surgical excision and consecutive radiation and/or high-dose chemotherapy should be considered in patients with MC sarcoma.

Future strategies are presently focused on the identification of molecular/genetic markers and potential drug targets in neoplastic MC. Investigation is addressed to targeted-drugs such as: tyrosine kinase inhibitors (imatinib mesilate, AMN107, desatinib, PKC412), non tyrosine kinase kit signalling inhibitors (geldanamycine, bortezomib, rapamycin) and monoclonal antibodies (denileukine diftitox, gemtuzumab ozogamicin).61 O imatinib mesilate is currently the only such drug approved by the Food and Drug Administraron (FDA) that might be useful in SM (ASM) associated to gene defects such the FIP1L1-PDGFRA fusion gene62,63 and others (excluding the c-kit mutation of D816V).64

Preliminary data of a study conducted by Carter et al demonstrates that anti-IgE therapy (omalizumab) may have efficacy in preventing anaphylaxis in patients with SM resulting from reduction of MC survival and overaccumulation.65

CASE REPORTWe present a case report of an 18 month-year-old, caucasian girl. She had a dystocic birth at 37 weeks and neonatal hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy with hypotension. She is a child of non-consaguineal parents and with maternal history of atopic dermatitis and latex allergy.

At four months of age the child exhibited a pruriginous microvesicular rash of the neck. It was diagnosed as atopic dermatitis and treated accordingly. However, there was a progressive worsening, showing extension of skin lesions to the trunk. Six months later she developed an erythematous rash of the face and trunk followed by respiratory distress and respiratory arrest and syncope. The child's mother gave her a cold bath with immediate recovery. She was treated with intravenous corticosteroid and oral anti-histamine in the emergency department. Apparently there was no prior episode of fever, cold symptoms, insect stings, trauma, sudden/intense temperature changes or histamine-release food/drink ingestion. Less than 24 hours after hospital discharge, a bullous dermatosis with transparent fluid of the face, neck and trunk started along with dyspnoea. She was taken to the hospital and remained admitted for 2 weeks, showing total remission under treatment with adrenaline, oral and topical corticosteroids, hydroxizine, ketotifen and flucloxaciline. The skin biopsy confirmed the diagnosis of mastocytosis.

Laboratory work-up showed raised levels of serum tryptase (381 ng/ml) and total IgE (1138 KU/L). Complete blood cell count, peripheral blood smear, serum biochemistry, skeletal X-ray, and abdominal ultrasound were all normal. Posterior evaluation showed a significant reduction of serum tryptase level to 25ng/ml. The absence of persistent significantly raised levels of serum tryptase, organomegalies and skeletal or peripheral blood anomalies eliminated the indication for bone marrow biopsy/puncture.

No further anaphylactic episodes occurred. However, daily episodes of flushing and urticaria elicited by heat, pressure and friction are noticed even under regular treatment with cetirizine, dissodic chromoglycate, ketotifen and avoidance of trigger factors of MC mediator-release.

There were no side effects of therapy nor a need for use of self-administered epinephrine prescribed.

Physical examination revealed urticarial skin lesions in areas that suffered pressure, resulting from child's handling. The remaining skin had a normal aspect and texture.

The c-kit mutation research is in progress.

CONCLUSIONSDuring the last few years, major advances in mastocytosis research have been made. Thus, by using defined criteria it is now possible to discriminate between MC disorders and other systemic diseases.

Mastocytosis is a relatively rare disorder, but its diagnosis is of relevance because of the multiple clinical manifestations and due to the risk of associated symptoms.

Although pediatric mastocytosis is usually benign, sometimes it can be clinically exuberant or severe and with a difficult diagnostic approach. Multidisciplinary work is therefore essential in order to diagnose, treat and manage the disease.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTSThe authors would like to thank to Dr. Orquídea Freitas (Hematology Unit of Dona Estefania Hospital), Dr. Margarida Lima (Hematology Department of Santo Antonio do Porto Hospital) and Dra. Susana Machado (Dermatology Department of Santo Antonio do Porto Hospital) for the information and enlightening given concerning the clinical case reported.